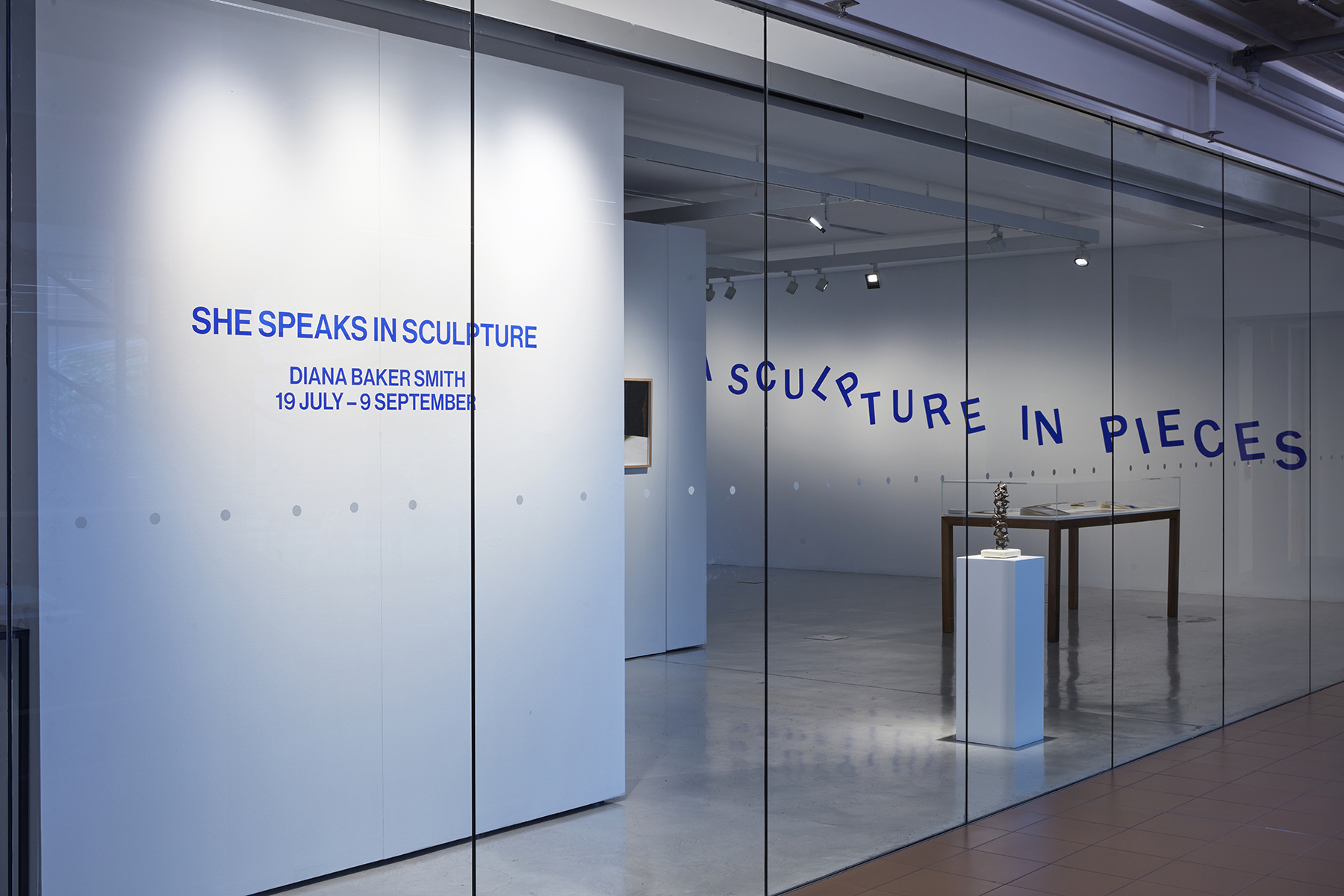

She Speaks in Sculpture

Amelia Wallin

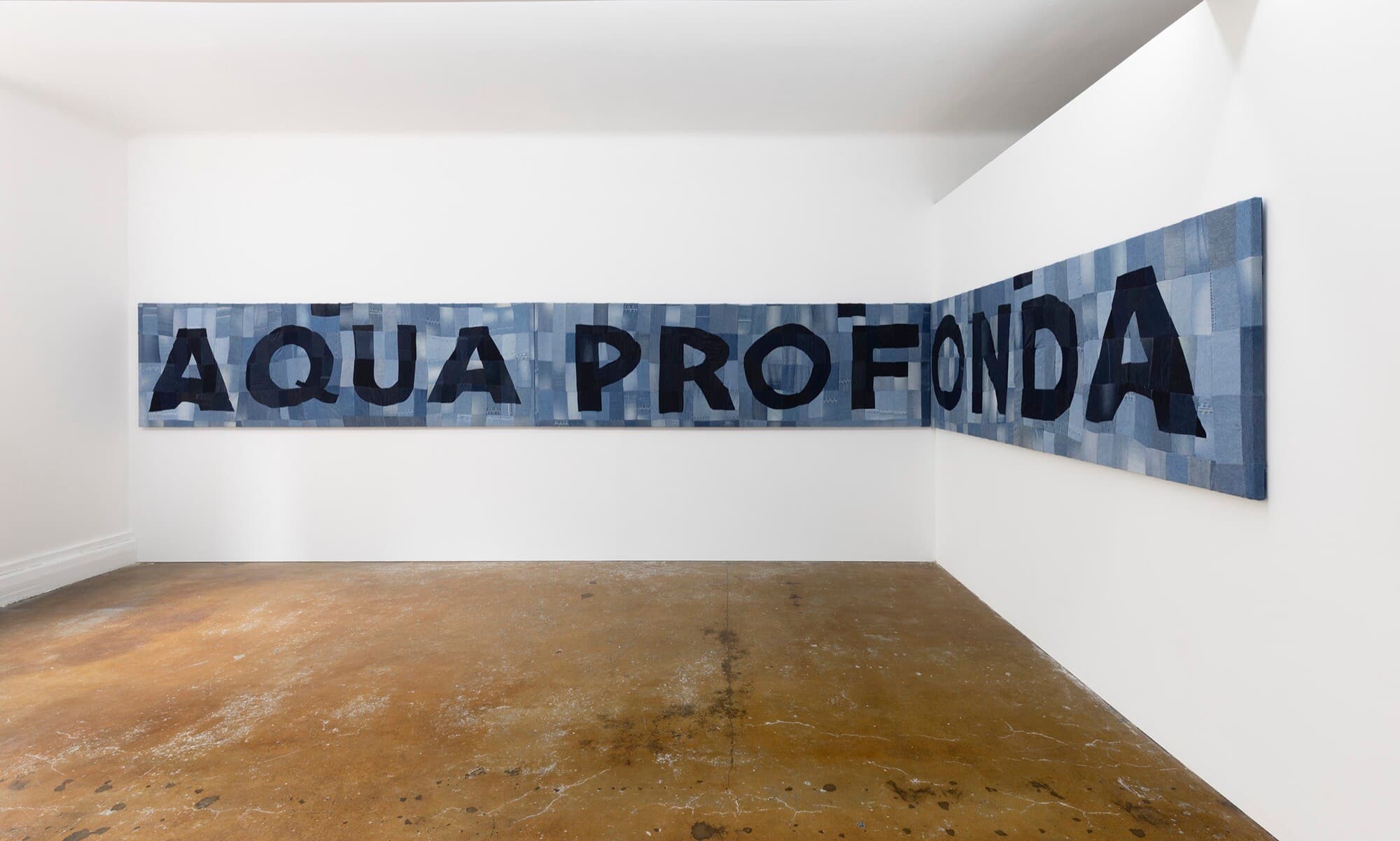

Diana Baker Smith’s current exhibition, She Speaks in Sculpture, raises questions about archives and legacies, and the absences that populate them. Who can speak for whom and with what materials? When a work enters the public realm, whose responsibility is it to maintain it? The exhibition takes place within UTS Gallery, a university exhibition space with a collection of 850 artworks. It is one such work in the collection that She Speaks in Sculpture is centred around: Growth Forms, a piece of public art by celebrated Australian-American artist Margel Hinder (1906–1995). More specifically, Baker Smith turns her attention to the work’s displacement and movement over six decades. Transplanted across various sites as a result of building demolitions and changing tastes, Growth Forms has been moved at least four times since it was first installed in 1959 including, at one stage, being cut for distribution as scrap metal. It has since been reassembled and as of this year is on permanent display in the UTS tower. This prominent position is still a compromise, as UTS curator Stella Rosa McDonald admits, as it stands with one side against a wall. Hinder’s intention was that the viewer could circumnavigate the column-like structure to experience the interplay of light and pattern through its form.

Growth Forms is not the only work of Hinder’s to have fallen (temporarily) out of public favour. In the early 1990s, Northpoint Fountain (1975) was decommissioned and relocated from its original site in North Sydney to the Macquarie University sculpture park, where it no longer operates as a fountain. It was originally commissioned for a public square next to a shopping centre that I frequented as a child and, although I can’t recall it with any specificity, photographs of the fountain feel inherently familiar, as if I know it on a bodily level. It is the same type of bodily memory that returns to me when I encounter Growth Forms newly installed in the UTS tower. I feel as though I am within the shadows of Sydney’s CBD, amongst the city’s particular blend of steel, glass and sandstone.

Previously Baker Smith has turned her attention to artists who operate on the edge of art history, such as performance artists Pat Larter and Philippa Cullen, through a process which she has termed “the artist as art historian”. Hinder’s modernist sculpture is a departure from the ephemeral performance practices of Larter and Cullen; Hinder is also not ‘forgotten’ in the same way. Indeed, Baker Smith’s is one of several recent projects that consider the artistic legacy of Hinder. She has recently been the subject of survey exhibitions Modern in Motion at Heide Museum of Modern Art and the Art Gallery of New South Wales, co-curated by Denise Mimmocchi and Lesley Harding (Mimmocchi contributed an excellent essay on Hinder for the catalogue of She Speaks in Sculpture). On a different scale, there is the familial history of Hinder, between her only daughter, Enid, and her great granddaughter, artist Jana Hawkins-Andersen. Enid manages her mother’s estate and lives with many objects and artworks from her mother, as documented by artist Rafaela Pandolfini on Medium. “I grew up surrounded by her works distributed all through my dad and grandma’s homes”, states Hawkins-Andersen in an interview for Suite7a. Reflecting on the similarities in their practices, Hawkins-Andersen continues, ”in a lot of her works she makes the metal textured and like it’s being eaten away, making it look fragile or soft … It’s like everything, every concrete state, is just a suggestion.”.

Sydney is a city that, since colonisiation, has articulated itself through continual renewal. When I return to the city for the purposes of reviewing this exhibition, I am disoriented. I notice that central station has been renovated (again?), and I attempt to visit one cafe, and then another, only to discover that both are no longer there. The concept of Sydney as a (settler-colonial) city that constantly erases its past and rebuilds itself is one explicitly addressed by the current exhibition Sydney Buries Itself, at Tin Sheds Gallery (see Tom Melick's Memo review here). Rather than chronicle the new structures and topographies with which Sydney seeks to renovate its image, She Speaks in Sculpture (like Sydney Buries Its Past) is interested in the absences and gaps that this renewal leaves behind.

A vitrine of archival photographs, a dual channel video work, and an arresting new photographic series are the centre-pieces of She Speaks In Sculpture. Movement Reconstructions No 1 and 2, photographed by Lucy Parakhina, focus on the quiet and often invisible work of restoration. Hands are shown in the process of touching, holding and transporting the maquette of Growth Forms, actions that are antithetical to the sculpture’s monumentality and steel materiality. This together with the inclusion of archival material and new photographs of the sculpture in transport visualise the link between historical gaps and material gaps through the Hinder archive.

The eponymous dual-channel moving image work She Speaks in Sculpture is exquisitely filmed by Gotaro Uematsu and edited by Kate Blackmore (one of Baker Smith’s collaborators in the collective Barbara Cleveland). In this film archival slides of Growth Forms under construction and in subsequent locations are intercut with imagery of the maquette being handled by Baker Smith, and footage of dancer Ivey Wawn in various urban sites. Baker Smith worked with collaborators dancer Ivey Wawn and choreographer Brooke Stamp to map the movement and motion of Growth Forms onto the body, using the ephemerality of dance to speak to the sculpture’s absence.

I am reminded of another work, Agatha Gothe-Snape’s Here an echo (2016) for the 16th Biennale of Sydney, that employed the use of dance in a similar way. Also working with choreographer Brooke Stamp, Gothe-Snape’s Here an echo like She Speaks in Sculpture centres the body in relation to an overlooked piece of public art. Both seek to capture the way that public art can leave its imprint on a city and its inhabitants on a subconscious or embodied level. On one screen Baker Smith’s blue gloved hands leaf through archival materials while on the adjacent screen Wawn performs in the various sites that once housed the sculpture, tracing its ghostly history through the streets of Sydney. This bodily record of absence is most pronounced when Wawn lies sprawled on the foyer of the UTS Tower, a site where Growth Forms formerly stood. We see, in a later shot, a grainy slide depicting the sculpture in that very spot. Viewed side by side, these encounters suggest two forms of archive, the ephemera and the body, both equal containers of memory and experience. In another shot, the camera pans the four-meter length of the sculpture, a web of blue cord holding it in place for transportation. This vulnerable state underscores the feat of Growth Forms’s movability across multiple locations, and the triumph of its survival.

There are multiple ways to write art history. Rather than intervene with the archive, She Speaks in Sculpture inhabits a productive space beside it. This position is multidirectional, with both the archive and the work informing each other. She Speaks In Sculpture accounts for the processes of preservation and development, rupture and repair on a material and embodied level. At the centre of She Speaks in Sculpture is a triumph of conservation and preservation, a story made clear by an artist doing art history.

Amelia Wallin is a curator and writer, with a focus on care, feminisms and alternate curatorial frameworks and models for instituting. From 2019 to 2022 she was the Director of West Space, and in 2022 she joined La Trobe Art Institute as Curator.