Tony Garifalakis, Scum Salon

Camille Orel and Jeremy George

Last week, the launch of A Foul Wind by critic/philosopher/poet Justin Clemens at Collingwood House set the salon scene nicely for us ahead of this review. We stood in the unbelievably tasteful living room of this creative space, replete with floor-to-ceiling windows looking onto blustering gum trees, massive Cy Twombly-esque canvases paired with whimsical pre-Raphaelite sketches and an exposed kitchen seemingly stocked exclusively with Le Creuset crockery. It was almost enough to make us question whether the grey and gritty Johnston Street we’d just stumbled in from wasn’t some kind of methedrine-soaked inner-suburban mirage. As Jennifer Coolidge’s character from The White Lotus breathily rasps while describing her Sicilian fantasy, this was so chic and nice.

The salon occupies a historically unique position within art-world ecologies, from the eighteenth-century’s Rahel Varnhagen, host to philosophical luminaries like Schlegel, Schelling and Schleiermacher, to Gertrude Stein’s infamous rooms at 27 rue de Fleurus, whose attendees included Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and James Joyce. Firmly institutional but nominally informal, the twenty-first-century salon—rebranded in one of its iterations as the “house gallery”—reminds us that an art world so utterly deracinated from the economic structures that defined classical patronage produces some seriously unstable and topsy-turvy hierarchies.

But there is a kind of space that has always managed to draw the salon and gallery together. Combining the icky sensation of intruding on someone’s private space in exchange for money and the alienated professionalism of the white cube is the stock in trade of small commercial galleries. And it is what drew us to Tony Garifalakis’s recent exhibition Scum Salon, which takes up the centre room, hallway and office space of Sarah Scout Presents, located at the top of Collins Street. The Paris End.

The exhibition is composed of four large fabric banners depicting low-res photographs of variously staged interior scenes, which have then been screen-printed over with a series of accusative declarations of the scummy variety. DIE YUPPIE SCUM reads the first banner, Scum Salon #4 (2022), as we enter the gallery corridor. Its purple block letters distort the image, their white outline giving the impression of seeing double. The screen tearing effect mimics the judder and blur of text on a film screen when the camera pans swiftly, as when we get a brief glimpse into Patrick Bateman’s room in American Psycho, whose spraypainted walls Garifalakis draws his text from. Behind these three words lies an image of an unattended domestic scene: a large ornate window embellished with billowing silk-satin curtains, an empty chair with matching cushions, a rose-tinted glass and a pair of gold slippers.

In 1988, New York’s Lower East Side saw a riot ensue after an influx of young professionals drove up rent exponentially in the neighbourhood. “Die yuppie scum” was the protestor’s call to arms as they clashed with police against mandatory curfews and the eviction of homeless encampments in the area. Perhaps in another world the abandoned scene in Garifalakis’s banner could depict the bedroom of one of those new yuppie neighbours, just run out of view to call the cops. But it could also have been brandished by the protestors themselves. Indeed, Garifalakis’s work is cannily anachronistic, evoking the popular imagery of a time when political divisions were allegedly more clearly pronounced, only to show that there are always points of mimetic contact, crossover and interplay during popular upheaval. Today, the banner could be held by one of the motley sovereign citizens and “freedom” fighters who organise outside Parliament, visible from Sarah Scout’s own window, every Saturday to deliver a spiralling list of sometimes heroic and sometimes incoherent anti-establishment demands.

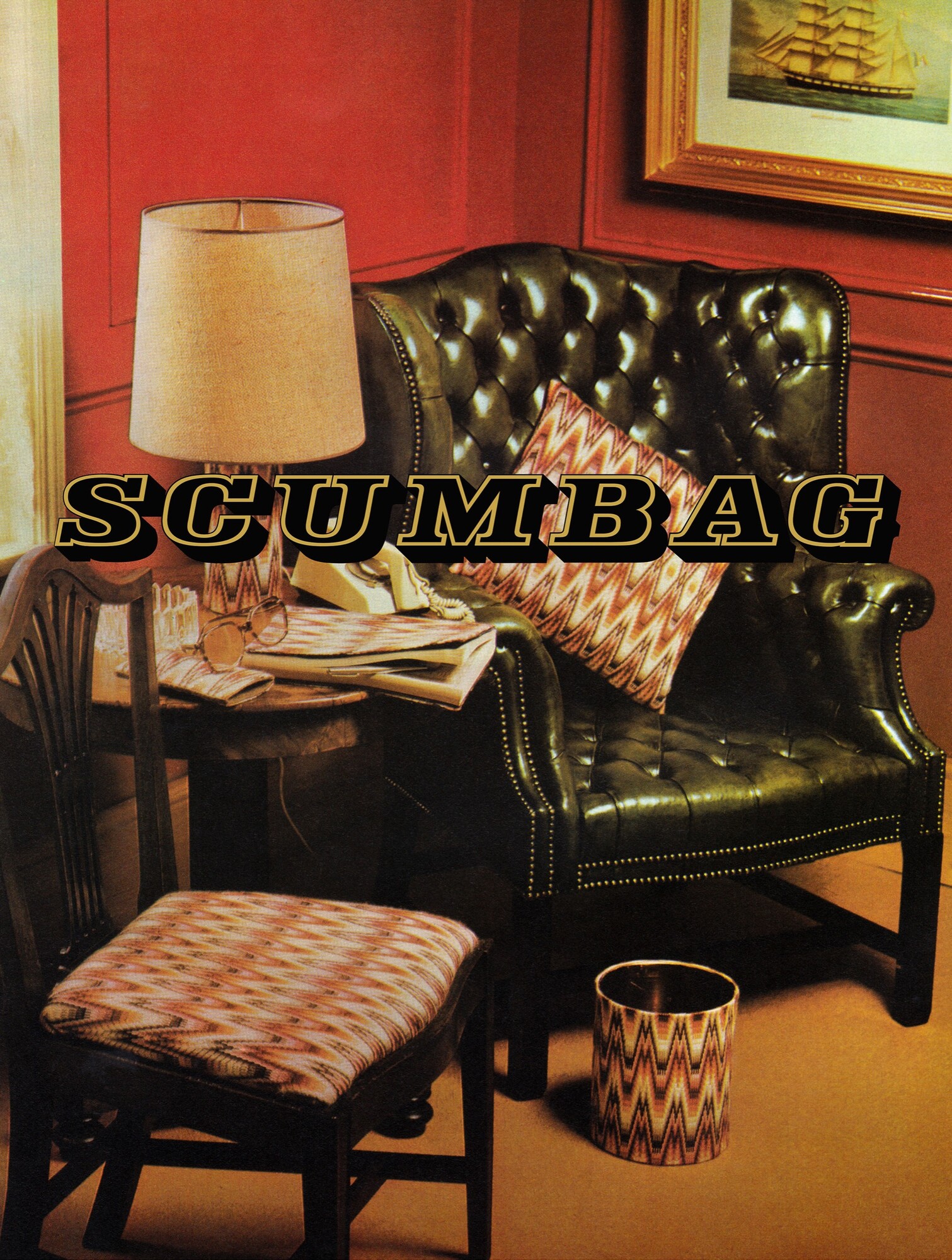

Each of Garifalakis’s four banners follows a similar formula: an unoccupied interior scene, individually dressed in a unique and rather gauche decorative scheme. They range from Franco Cozzo-Rococo-Egyptian-glam, through to Ikea-post-painterly-geometric-mod. Each is superimposed with an emboldened phrase over the top, giving the impression that we are looking at a series of movie posters turned into banners. Take Scum Salon #3 (2022), which is hung on the right wall as we enter the gallery’s central room. It pictures a red-hued interior adorned by a smorgasbord of antique furnishings pulled from disparate decorative trends. On the chesterfield armchair sits a throw pillow covered in a geometric zigzag fabric that teeters on the line between Y2K-déclassé and Missoni-chic—an accent repeated across all the soft furnishings throughout the room. Printed onto a cotton-linen blend fabric banner, Garifalakis has screen-printed the word SCUMBAG over the scene in Hollywood-style black-and-gold italics.

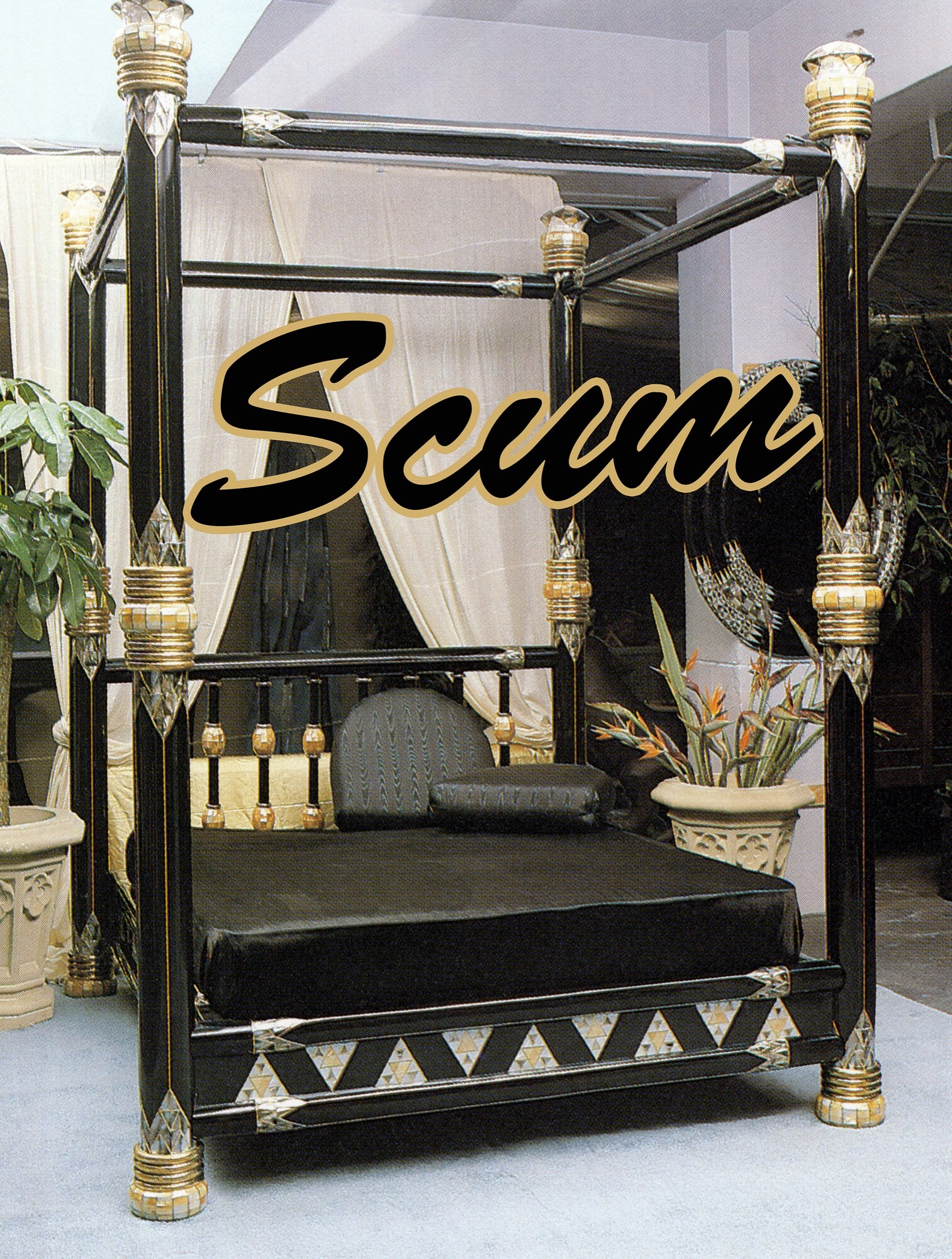

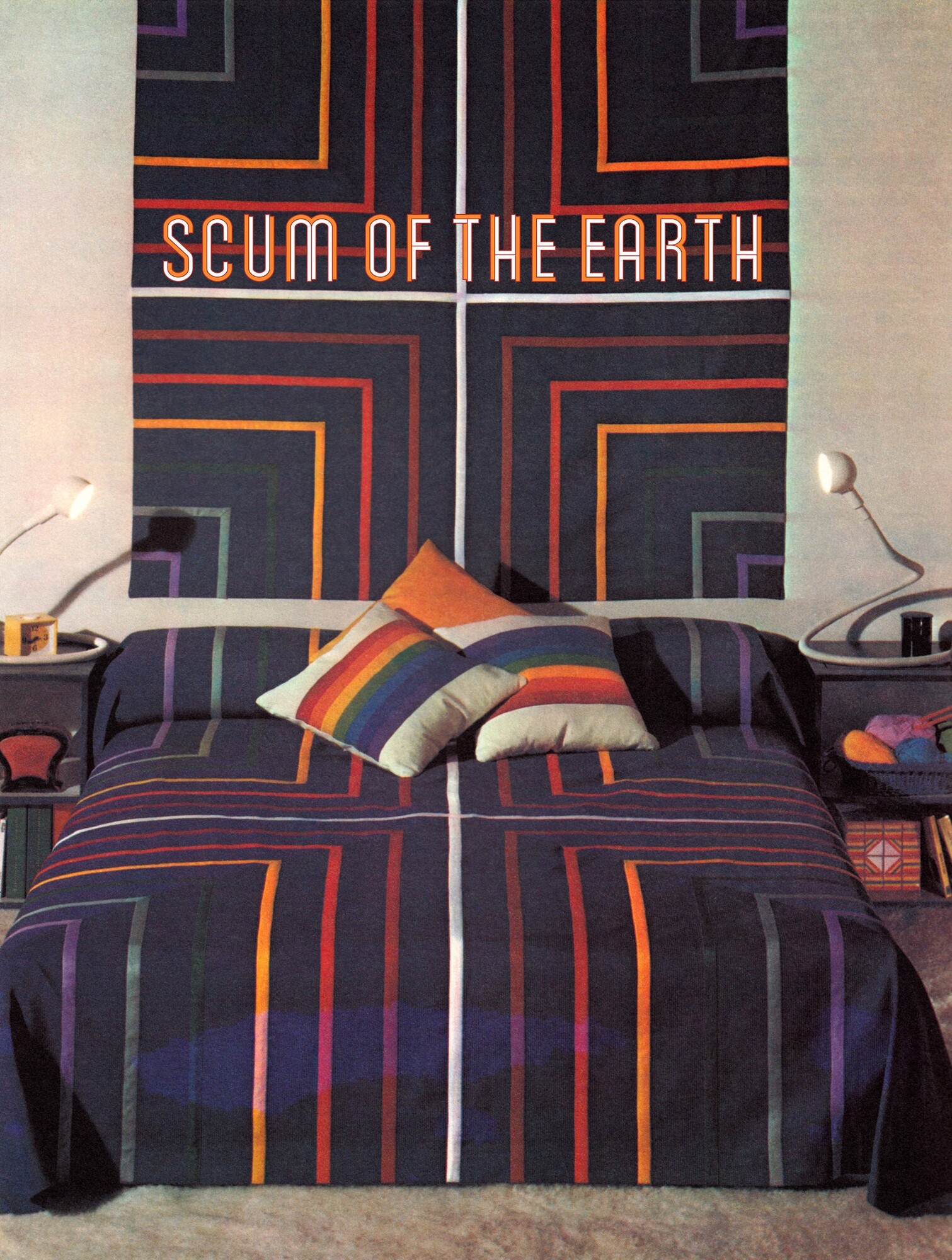

Across the gallery room hangs Scum Salon #1 (2022), with SCUM scrawled across the image in more fluid strokes. Behind sits a glossy black four-poster bed with gold detailing which sits in what looks like a static showroom cast in a similar ashen hue to the one we are standing in. Looking to the opposite wall back in the hallway, the two spaces divided by a phony wall for that open-plan feel, hangs the fourth in the set, Scum Salon #2 (2022); it is an uber symmetrical, futuristic boudoir set complete with its own banner that hangs above (and matches) the post-painterly bed cover. Garifalakis has printed SCUM OF THE EARTH to line up seamlessly with the background, a banner on a banner on a banner.

In 2014, Garifalakis presented two series of works entitled Mob Rule and Bloodline that were exhibited at the AGNSW and NGV respectively. Each series took images of members from politically and culturally elite establishments such as the British royals and then blocked out their faces with black paint, obscuring individual identities and leaving behind only imagistic traces—say, a crown, or jewel, or sash—of the institutions that these figures have come to represent. The “faceless man” also happens to be a foundational term of modern Australian politics and the redacted document is its icon. The term was first effectively used by Robert Menzies to attack ALP factional apparatchiks, famously resurfacing in Kevin07’s resignation speech after he was replaced by Julia Gillard following an internal coup d’état. The faceless man represents the seamy underside of political power, from post-mass membership branch stacking to Epstein and BHP. As even the New York Times has noted, ‘Australia May Well Be the World’s Most Secretive Democracy’.

Garifalakis is in no uncertain terms a member of a particular class of the secretive cultural elite: a professional artist represented by a locally prominent commercial gallery. Of course, he already knows this and has masterfully worked it into his practice. And so, with what we take to be his blessing, as we head toward the gallery, we imagine a young professional couple rocking up to the ritziest part of town to buy one of his banners which sardonically reads “scum of the Earth”, bringing it home to hang above their four-poster bed. It suits the space perfectly. Looking up at their newly acquired piece of art before falling asleep, the couple discusses at length its potential hidden meanings, historical references and innuendos, chuffed to find themselves in on the joke. Hahaha, we mockingly laugh at the foolishness of this imagined life. And then we think about how great it would be to have one of these above our own bed…

The level of self-reflexive nuance and irony at play in Garifalakis’s body of work has been consistently impressive. But in Scum Salon Sarah Scout has drawn itself into the vulgar bourgeois decadence Garifalakis seems to be poking at. The scandi-style sofa in the corner is upholstered in a geometric fabric much like those pictured in Scum Salon #2 (2022). And the otherwise beautifully sculpted ceramic vessel by Franco-Beninese artist King Houndekpinkou, placed on the room’s sculptural ledge, clashes with the rest of the space, just like the Y2K-era throw pillow sitting on the nineteenth-century Victorian era Chesterfield depicted in #3 (2022). These are fixtures of Sarah Scout unspecific to Scum Salon. Even the bubble-wrapped and dusty something stowed beneath the couch the gallerists don’t bother to properly conceal (very Patrick Bateman); the marble side table adorned with Art Collector magazine and two issues of Vault is scarred with coffee-rings. Does this not also signal a more general curatorial “failure”? That is, seemingly purposively, Sarah Scout does not try very hard to distinguish itself from Scum Salon’s object of critique but rather passively accepts that it just is this very object (neither concealing itself nor playing itself up to the point of hyperreality).

The small commercial gallery’s roleplay as personal art advisor walks a tightrope between familiarity and cool-headed professionalism, and the curatorial decisions here produce the unintended effect of underworked posturing. It struggles to commit to the austerity of the serious commercial showroom, the comfortable authenticity of the lived-in salon, or indeed the spectacle of a gallery that has purposely restaged a meta-simulation of Garifalakis’s work. What does it mean that Sarah Scout presents Scum Salon as addressed to itself but refuses to fully embrace any of the three curatorial options that would allow the gallery to either suppress the accusation or own it?

Scum Salon, like The White Lotus, reflects a contemporary tendency in culture to present exaggerated and caricatured indictments of the inanity of the elite class. The trend provides cathartic relief both ways. Those excluded feel vindication at the fictional fates of the decadent; the beneficiaries enjoy a masochistic self-cleansing while keeping their luxuries. The didacticism of Garifalakis’s Scum Salon participates in this zeitgeist of the anti-elite. But its presentation invites a different question. It reminds us that from cultural critique does not necessarily follow cultural change. In fact, the object of critique, by understanding itself as such, becomes absolved and thus free to do…absolutely nothing. As Patrick Bateman has it in his famous confession “even after admitting this…I gain no deeper knowledge of myself”. Scum Salon deftly stages the uselessness of the confession. Does it allow for penance?

Camille Orel is a writer living in Naarm / Melbourne. Jeremy George is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne.