I remember you

June Miskell and Talia Smith

It is wet and muggy the day we visit Carriageworks, fitting conditions to view I remember you—an expansive solo exhibition by Salote Tawale that takes its cues from the artist’s Pacific Island heritage. Amidst the subtropical Sydney steam, we reflect on our own memories of returning to our respective ancestral archipelagic homelands (The Cook Islands and Sāmoa for Talia; The Philippines for June). The qualities of the humid heat are hard to describe (sticky, damp, oppressive) because it is so much more about how it feels, and sometimes feeling surpasses language. Similarly, memory can also be difficult to articulate. One can never be too sure of what is real or imagined since there is a certain slipperiness or fragmentation to how memories are invoked in the present. It is for these reasons that our memories distend the spatial and temporal orientations that distinguish then from now, there from here. Along this continuum, how might identity be formed through memory, both personal and collective? If memory is a vessel that holds the capacity to transport us elsewhere to another time and place, then how do we moor ourselves? How do we avoid getting lost in the sea of nostalgia that memory tempts us with?

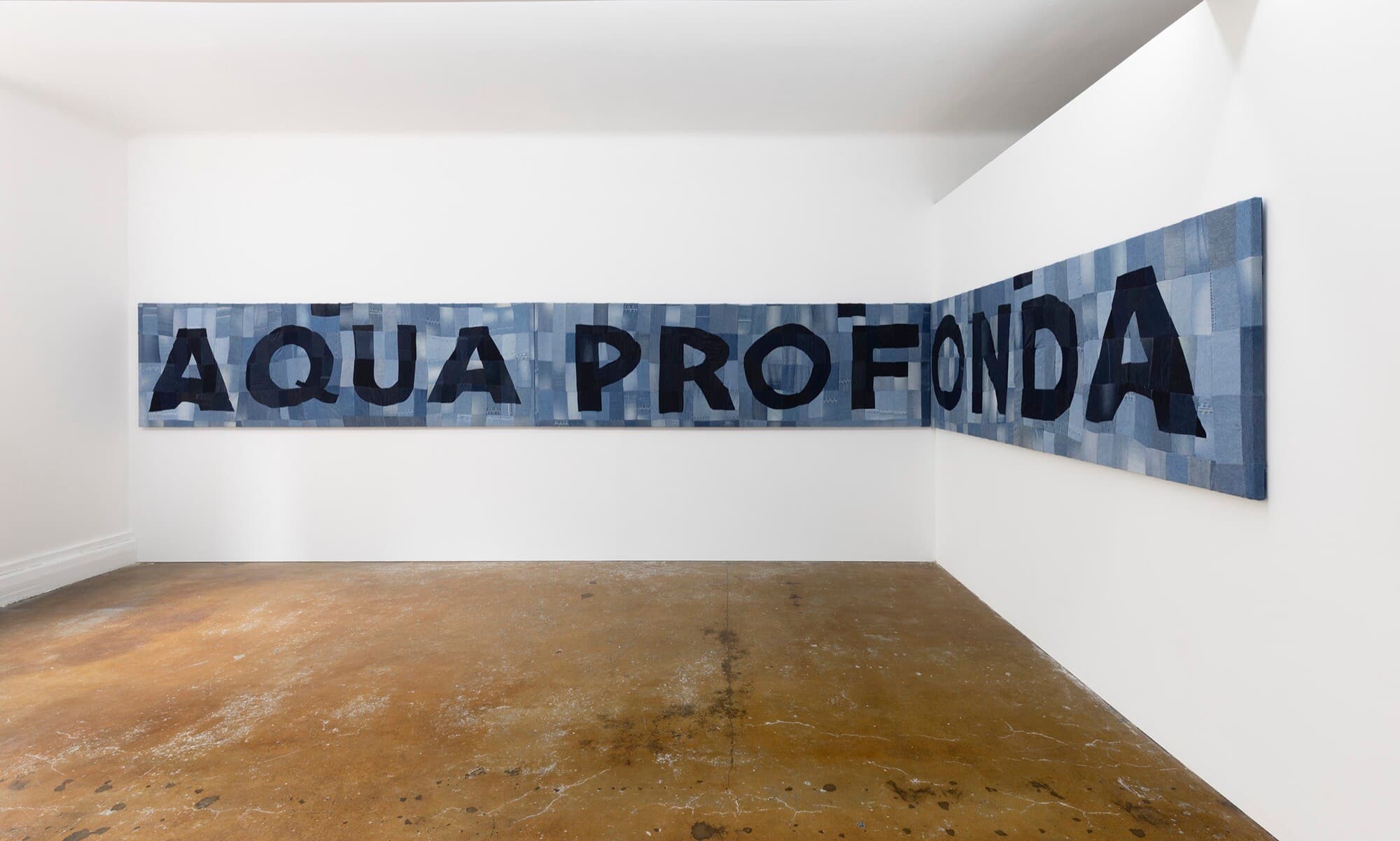

Such questions buoy our viewing of I remember you. Curated by Aarna Fitzgerald Hanley, the exhibition transforms Carriageworks’ industrial-chic architectural interiors—Public Space and Bay 21—into Tawale’s own personal “memory bank” through an installation that brings together painting, sculpture, and karaoke (yes, karaoke!). I remember you draws upon Tawale’s own recollections to explore notions of memory, displacement, identity, and belonging—-themes characteristic of her practice. In recent solo exhibitions such as I don’t see colour (2021) at Perth Institute of Contemporary Art and Love from here (2021) at Murray Art Museum Albury, Tawale peeled back multiple layers of memory in an exploration of her cultural identity, diasporic experience, and the liminal realities of being from a mixed heritage. Across both exhibitions were makeshift house-like structures made from a combination of wood, bamboo, and sheets of corrugated iron that enclosed a TV screen. While the video works playing on each screen in I don’t see colour and Love from here differed, the makeshift and familiar “home” Tawale reconstructed provided a contemplative repository for dwelling in these memories. Indeed, I remember you gathers and builds upon Tawale’s long-abiding probes into the power of memory and self-representation from the perspective of her Indigenous Fijian and Anglo-Australian heritage.

Entering Carriageworks, we encountered two simultaneous greetings: the fourteen-meter-long bilibili (a traditional Fijian watercraft used to transport goods and people downriver) made of bamboo, nylon, rope, tarpaulin, and found objects comprising the work No Location (2021) and bumping into Tawale herself as we walked toward the raft from opposite directions. We know the artist both through the interconnectedness of the local contemporary art world and by us all being archipelagirls (a portmanteau we’re soft launching in this review). As we briefly caught up with Tawale, she recalled her childhood memory of visiting the Fiji Museum in Suva where she encountered the bilibili, seeing it as a vessel that would allow her to live between so-called Australia and Fiji. However, a key piece of information that forecloses such a desire is that bilibili’s can only travel forward with the current, never turning back.

Originally staged as part of The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in 2021 at the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art, this iteration of No Location positioned within the Public Space of Carriageworks has more room to breathe. In No Location, Tawale reinterprets the traditional method of constructing a bilibili. Using the labour-intensive processes of bundling and binding bamboo to create the raft’s structure, Tawale distinctly incorporates tarps and ropes—everyday materials typical of her previous work—alongside personal items to accompany her on her journey. Such essentials displayed on the exterior include a portable Esky cooler, a bike, a half-filled water canister, a charcoal grill, and cooking utensils. Inside the shelter rests a pillow and a leopard print fleece blanket—the garish pattern of which clashes perfectly with the intricately woven Fijian masi mat below it. More comical (or poignant) is viewing this work in Eveleigh as we are nowhere particularly close to the water, and so this boat appears beached with no place to go. Perhaps instead the journey that the bilibili represents is not so much physical as it is metaphorical—one where the comforts of memory are enough to tide one through experiences of displacement.

Guided by the orientation of the bilibili and the direction of the subtle wavy currents painted on the adjacent wall, we moved into Bay 21—the second and fuller room of the exhibition. Tawale’s manipulation of recycled materials continues in the series of masks that hang above us from the yellow gantry crane, each individual adornment (mask) indexing memories of people, moments, and objects that are significant to Tawale’s life. Masks, broadly speaking, are connected to rituals that are spiritually or socially significant across various cultures, often in relation to funerary customs, healing illnesses, and protecting oneself from evil spirits. On the other hand, masks are commonly worn during festive occasions and dramatic performances in which characters become animated. And so, the bold presence of these sculptural portraits interlinked by colourful lengths of rope and carabiner hooks, enacts a memorialisation, and suggests that if miniaturised they might be worn on the body as keepsakes. Accessing identity through embodied interactions with memory—be it from smell, sound, touch, or feeling—is a common theme throughout Tawale’s work and one that becomes responsive as we circuit through Bay 21.

I remember you necessitates an intimate and embodied viewing experience with Tawale’s material arrangements. As we are invited into these spaces—laden with Tawale’s personal histories—with welcoming arms, there is also a caveat that maybe not all is as it seems. Case in point—a vibrant carnivalesque plywood cut-out depicts a posed Tawale and her sister in front of a gated swimming pool. In the lower panel, the Swedish word “Hej!” is rendered in Ikea yellow—a simultaneously humorous, apt, yet disarming welcome into an installation that takes the home as a point of departure (and arrival).

At first, reading this work comes across as tongue-in-cheek but upon further reflection, there is something almost unsettling to this standee. The cut-out warrants the participation of the viewer through the performative act of placing one’s own face in the negative space. While this photographic opportunity appears innocent at first, at stake for a (white) viewer is the temporary embodiment of a raced and gendered body that is potentially not of their own experience—-a body that has historically been gazed upon or “put on display,” so to speak. It is theatrical with an element of danger, everything is not always as it seems. Tawale is clever in facilitating what histories are revealed to the viewer and how we might access and read these moments of encounter. At the right angle, while peering through the cut-out faces, a painted plywood cut-out of Tawale posed inside the doorway of the house in the distance returns our gaze—a “gotcha” moment. Sometimes a view into Tawale’s memory may also at any moment point the spotlight back on us, forcing reflection on our complicity in structures of racism and looking.

In the centre of Bay 21 sits a partial reconstruction of Tawale’s ancestral family home, made from corrugated iron, wooden planks resting on cinderblocks, and complete with an electrical wire hanging overhead. Framing the space are various smaller plywood cut-outs depicting floral arrangements and a large hibiscus painting on the wall. Though entry to the house is strictly not allowed (at least from the front, we are told by the gallery invigilator), varying apertures allow you to peer inside. Together, they reveal richly patterned textiles and a suite of framed photographs on the back wall featuring food, an x-ray of Stuart’s (Tawale’s French bulldog, named after the inimitable cultural theorist Stuart Hall) back legs, and an iconic photograph (witnessed once at an artist talk) of Tawale herself, pants down and pissing in the bushes—a classic example of Tawale’s tactful use of humour in her approach to self-representation.

At the back of the gallery space is an open-air backyard comprised of a washing line supported by bamboo poles and cinderblocks that span the width of the room. Hanging on the line are a series of pegs, a characteristic black tee-shirt of Tawale’s, a pair of black joggers, and sweat-stained insoles. Alongside this, there is a collared shirt whose sleeves stitch together a timeline of Fijian clothing in Dutch Wax fabric (also known as Wax Hollandais). The arms of the shirt fall onto the ground as if being pulled in opposite directions—-one towards the painted water lines at the base of the wall, and the other toward the perimeter of the room. The exaggerated arms of the shirt act as a metaphor, as if they are attempting to reach and close the spaces or holes inherent within our memories. For Tawale, the home (and its various manifestations) is a key site of memory and its placement and scale within the gallery space attest to this.

The last space we eagerly encounter in I remember you is an open karaoke room attached to the back of Tawale’s reconstructed family home. It is a dim and comforting space blasting familiar tunes, offering two microphones for the viewer to sing and a worn soft beige leather sofa enticing us to stay a while. Sinking into the worn leather, we bask underneath the fluorescent disco lights that dance across fake floral vines hanging overhead. The karaoke room invites us to sing along to a collection of eighties and nineties rock ballads and pop hits such as I Want It That Way (1999) by Backstreet Boys and I Remember You (1989) by Skid Row—the exhibition’s namesake. On the TV screen while the lyrics appear the imagery montages a retrospective compilation of Tawale’s oeuvre interspersed with moments from her everyday life. The karaoke room feels like Tawale’s practice distilled, it is a glimpse into how her memory is enshrined and embodied throughout the rest of her practice. As the host of the super gay, super sad, Sad Dyke Sundays (SDS) at the Bearded Tit in Redfern, it is fitting that Tawale reconfigures and manipulates a typical karaoke room here in I remember you.

While the exhibition speaks to Tawale’s own personal memories, there is an afforded intimacy in which we cannot help but reflect on our own personal histories. Through Tawale’s work, the internal struggle of being mixed-race and living on stolen land is intricately interwoven. To better understand her own identity—where she is from and where she is now—I remember you collapses and expands various memories of Tawale’s across time and space. For us, these moments of shared contemplation and remembrance viewing the exhibition transports us across the oceans from so-called Australia to Fiji to the Cook Islands, to Aotearoa, to the Philippines, and back again. And though the memories shared with us in I remember you are Tawale’s own, after all, the vessels that preserve them embolden us to consider our migratory histories and how we moor ourselves in the present.

June Miskell is a writer and researcher living on unceded Gadigal and Wangal land. She teaches at UNSW Art & Design, Sydney where she is currently undertaking her PhD. Talia Smith is an artist, writer, and curator based in Sydney on Gadigal and Darug land. She currently works as the Curator of Blacktown Arts.