Simon Zoric: Root, hog, or die / Lou Hubbard: 1976

Chelsea Hopper

When I first met artist Sanja Pahoki at an opening in 2011 she told me: “Making art is a lot like taking a shit. Occasionally you have to wipe a few times.” I’ve always wondered if Pahoki told her students at the VCA this. It seems she has. Simon Zoric, who studied art where Pahoki teaches, is currently holding his first commercial exhibition and it contains six fabricated cast-aluminium cat litter trays, shovels and cat faeces.

Each tray is evenly spaced on the concrete floor of the gallery. A lone polychrome version sits in the middle, separating one black and one white iteration placed at the back. Monochrome red, yellow and blue sit together, reminiscent of the modernist preoccupation with the elements of colour theories. It reminds me of Mike Parr’s vomit piece The Emetics (Primary Vomit): I’m Sick of Art (Red Yellow and Blue) from 1977, where he spews up monochrome paintings in the same set of colours. Like the American minimalists in the 60s, the aesthetic of Zoric’s work also reduces itself to its necessary elements, achieving simplicity. As Andrew Liversidge notes in his exhibition text, “Zoric has a very economical way of re-presenting unlikeable things at scale to make them desirable… in the right format and correct size without sacrificing sincerity.”

Zoric doesn’t actually own a cat. Amelia Winata tells me that he asked her if she could save some of her cat’s faeces to use as a dummy mould, but she (the cat, Agnes) never produced anything as long and healthy-looking as the final ones that lie in the litter trays. Like human faeces, the size, shape and colour are dependent on what we put into our bodies. The cat shits, delicately placed and arranged in each of the trays, are just as convincing of the real deal of a healthy feline: “deep brown in colour and feels not too hard or too soft or mushy.”

This is not Zoric’s first foray into fabricating shit. His polished bronze replica of his own faecal offering, stuck on a large chrome-plated stainless-steel square mount, One of the Last Great Works of the 20th Century (2018), is also a nod to Italian artist Piero Manzoni, who is well-known for canning his shit and calling it art. What is Zoric doing with this shit? Is he taking his self and his own waste too seriously? For me, Zoric’s artistic endeavour into fabricating shit pursues an anti-elitist approach to self-mockingly critique the artist-as-subject. Previous works—for example, Credentials (2016), a pair of framed university degrees Zoric acquired or The Finest Actor of Our Generation (2016), a signed headshot of the artist—humorously toy with the preconceived “requirements” one needs to commercially succeed as a contemporary artist. As with the emergence of Pop art, Zoric’s refined cat litter trays play into the status of what are considered “high” and “low” artforms and transform artmaking away from being an ‘elitist’ activity.

Each of the litter trays and scoops was cast overseas. Gallerist Adam Stone tells me that when Zoric first mailed the cat litter trays, they were seized at customs as he set the value of them suspiciously high ($99) and had to resend a new batch. The litter is also fabricated to mimic real cat litter. Up close, the litter is made of fine crystals of quartz, apatite, howlite and tourmaline: the same material to make holistic massage wands. The trays are coated in automotive paint, recalling Ian Burn’s Blue Reflex (1966—) paintings. They also relate to Burn’s 1981 essay about the outsourcing of artistic production written for Art & Text titled “The Sixties: Crisis and Aftermath.” The relinquishment of traditional artistic skills and materials was one of the defining features of art from the 1960s, with Burn naming this phenomenon “deskilling.” He writes: “Each of the early sixties styles was marked by a tendency to shift significant decision-making away from the process of production to the conception, planning, design and form of presentation.”

As it happens, Root, hog or die is a reference to an 1800s catchphrase of an early colonial practice of letting pigs loose in the woods to fend for themselves. It’s an idiomatic expression of self-reliance and Zoric seems to be hoping that his work has this same sense of self-sufficiency. The phrase is also quoted by Donald Judd in an interview by Bruce Glaser published in 1966 with Frank Stella in which they discuss and clarify—as editor Lucy R. Lippard notes—”the numerous prevailing generalisations about their work.” Re-reading this interview, Judd and Stella (who were part of the East Coast American minimalist scene) go to great lengths to describe an effort to have things be themselves and at the same time be exactly what they seem: “What you see is what you see”, remarks Stella at one point.

The theme of deskilling is not uncommon in Zoric’s work. His self-published book One Hundred One Word Poems (2018) is exactly what it claims it is: one-hundred poems, each one word long, and each taking up one page of the book (“Sentence” is a personal favourite). In fact, at another gallery on the other side of town is an exhibition by another of Zoric’s former teachers, Lou Hubbard, who in 2020 self-consciously published a near-identical paperback to Zoric’s titled Train Crossing. While Hubbard’s book isn’t poetry but heavy with image and text, she deliberately decided to include the same number of pages as One Hundred One Word Poems. “I like the idea that they might all influence each other” Zoric tells me. I look forward to the next print run.

Hubbard’s show is at Savage Garden in Carlton North, a backyard shed-turned-gallery run by two more of Hubbard’s former students, Matthew Ware and Jordan Halsall, completing a satisfying constellation of inter-generational art practices and spaces.

Lou Hubbard: 1976 was only open across three Saturdays in the second half of July. At the opening, puppies and babies mingled among the crowd of Garden aficionados rugged up in thick mohair scarves and vintage bomber jackets. The four drawings on display were all made some time ago, during Hubbard’s second year of a creative arts degree at the University of Southern Queensland formerly known as DDIAE: Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education in Toowoomba, Queensland. Her teachers, amazingly, came from prestigious London art schools: Royal College of the Arts, Chelsea School of Art and Slade School of Fine Art. At the same time Hubbard was studying, Robert Gist, an American actor and film director was the head of art school. Even the poet Bruce Dawe was one of her tutors.

This eclectic mix of British and American educators at the creative outpost Hubbard found herself in as a teen was completely at odds with living in arguably one of the most conservative towns in Australia at the time. Censorship under the Joh Bjelke-Petersen one-party (today known as the National Party) state government—which repeatedly breached civil liberties—coupled with increasing police powers and public presence, resulted in a mass exodus of artists and curators from the state in the early 80s, many believing a successful future was only possible if one were to move.

Hubbard left in 1979 to Sydney, shifting her focus away from artmaking towards a career in the film and television industries where she produced numerous documentaries and wrote and directed short films. It was only in the 90s, stumbling across the work by another artist also called Louise (the great Bourgeois) at the National Gallery of Victoria, that influenced her return to artmaking. Gently nodding her head, Hubbard describes to me this moment of seeing Bourgeois’ work as “something was happening there”, while gesturing her hands up and down in front of her, “that I wanted to do.”

During our long discussion, Hubbard points to the gap between my foot and the coffee table. “That space between things”, she says, “is what I’m interested in … trying to capture that.” This innate intention Hubbard literally gestures to me can be found in the spatial experiments across the page of these highly abstracted drawings made when she was 19. Here, her spatial thinking is apparent to me in the layering of colour and tone, of shape and colour, within the intense and chaotic scrawling of the mark-making.

Each of the four drawings are housed in custom-made acrylic frames, allowing for the creases, faded edges, knicks, and pinholes to float freely without much of the visual interference or distractions carried by a traditional wooden frame. Because of this, they carry a tomb-like effect reflecting the lapse of time between when the works were made and now.

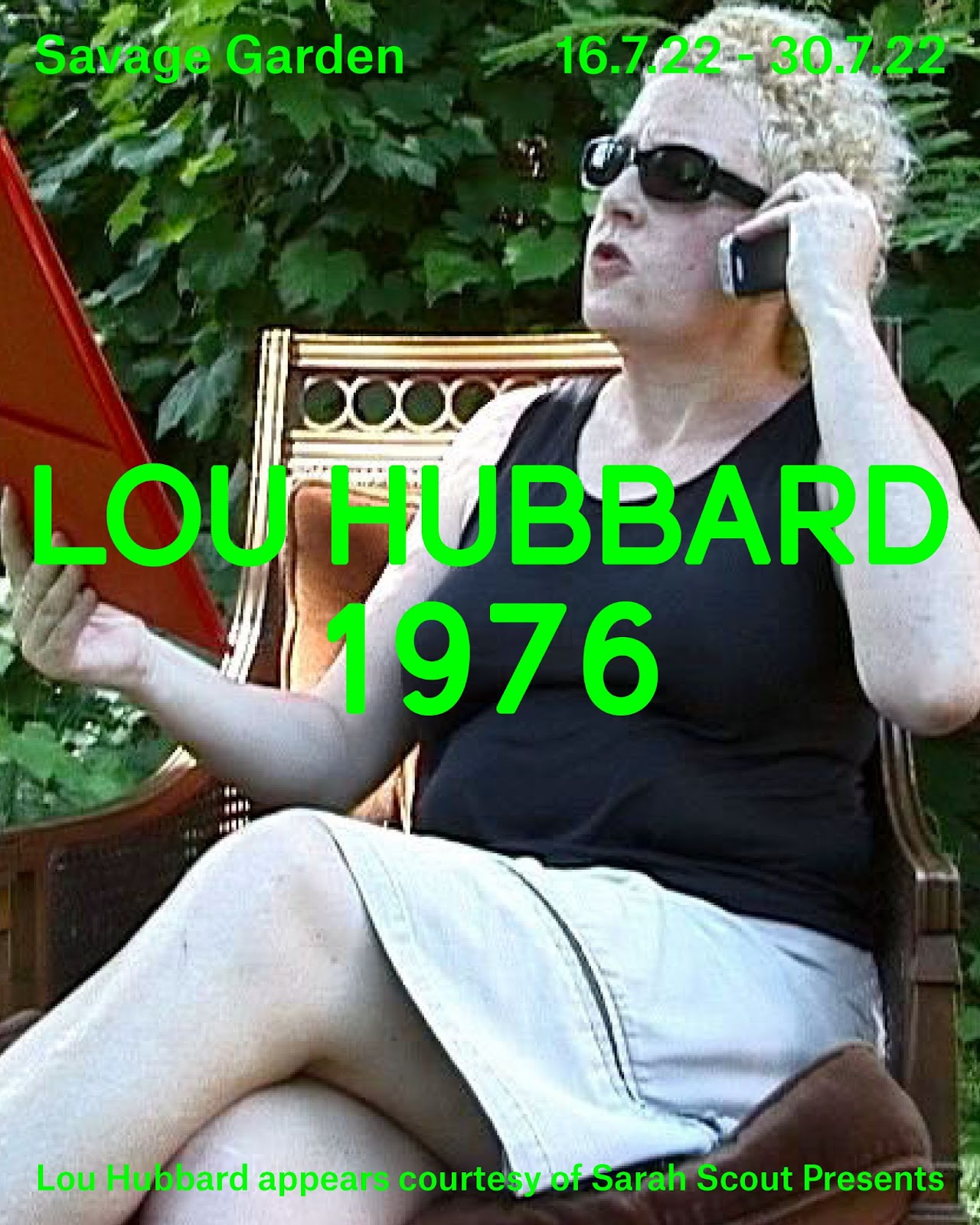

The exhibition’s invite also bends time. It takes as its backdrop a still from Your call is important to us, a video work by Helen Frajman made in 2004. Hubbard is cropped into frame, sitting in a backyard on a cushioned chair, holding up a red clipboard in one hand, and a mobile phone pressed to her ear. Her rectangular black rounded sunglasses and fuzzy bleached blond cropped hairdo are telling of an early-2000s aesthetic. It is the last public work Frajman made. According to Frajman, she dabbled in photography and video in the late 70s and early 80s. The video is a one off that, at the time, she included in a group exhibition that she curated of all the artists represented at M.33: an organisation she runs devoted to publishing books on the work of Australian photographers. This choice is surely no accident, or perhaps it is a strange coincidence: Hubbard was turning 46 in 2004, and it is also 46 years since the year 1976.

The text overlayed detailing the exhibition is in a chroma key green, a colour I like to think of as synonymous with Hubbard (and now the branding of Savage Garden). The colour’s suggestive nature of disappearance or invisibility first appeared in the hands of Hubbard as a roll of lycra in 2002. It’s used to shroud objects, acts as a stage/platform for other pieces and even opted as a wall colour. The fabric is memorable as a long billowing curtain, in her 2015 West Space solo exhibition, Dead Still Standing, along with featuring as the backdrop in Debut Stand (2014), and even stitched into a short frill on custom-made underwear made for an ARI fundraiser.

Sitting outside the gallery-shed is a big, lumpy piece of Styrofoam with an old Teledex case sitting on top, signed “L. HUBB 2014.” While this is utilized as a prop to keep the gallery door open, it is also an important reference point to Hubbard’s sculptural work of recent decades. The white, awkwardly battered lump is repurposed from an older work, and the Duchampian-Teledex is a reminder of the sustained practice of recycling objects: “mounting a rescue” as Hubbard calls it.

What value is there going “back-to-school” for an artist and teacher? It seems there’s a lot to pick at. Ongoing interests and obsessions are given an origin story. Repressed memories finally get airtime. Think of Mike Kelley’s seminal work Educational Complex (1995), which remade models of all the high schools he attended and houses he grew up in. Or even fellow VCA graduate-turned-lecturer Masato Takasaka’s commitment to remaking his high school abstract paintings over and over. The conceptual artist Mutlu Çerkez—who titled his work based upon a future date in which he would remake it—also comes to mind. This collapsing of linear time rejects the idea that artists must always aim to produce new, finite and resolved “outcomes.”

These exhibitions, 1976 and Root, hog or die, illustrate the serendipity of the teacher-student relationship. Two artists at different points in their career reflect on one another. Zoric is having his first commercial solo enterprise in his early 40s, at the same age Hubbard was when she started making art again back in the late 90s after her 70s art school stint.

Zoric and Hubbard’s work continues to upend ideas of power and status between objects, time and subject matter. Their influence on each other, consciously or not, draws on the parallels made both as teacher and a student. Whether he likes it or not, Zoric, who now teaches at VCA, will undoubtedly have the same effect Hubbard has had on him.

Chelsea Hopper is a curator and writer who runs 99%, a gallery housed in the Nicholas Building.