More so than most other artists of his generation, Robert Smithson is a figure who has encouraged something like a ‘cult following’, in which admiration for the man and for his work can be difficult to separate. In writing about Smithson, many art historians and critics seem to drop their default pose of sceptical historical distance and play the role of fans, often seeking less to contextualise and interpret Smithson’s work than to appreciate its profundity and significance. Of course, there is much in Smithson to attract this sort of attention: the labyrinthine web of references to ideas cobbled together from disparate fields (minerology, thermodynamics, science fiction, urbanism) that mark his often near-impenetrable writings and underpin his works; his self-conscious position as an outsider in relation to the dominant formalist concerns of the New York art world into which he emerged in the mid-1960s (after something of a career false start as a painter of expressionist religious imagery earlier in the decade); and the unfinished, unresolved nature of his oeuvre as a whole resulting from his death at 35 in a plane crash while surveying the site of a planned earthwork in Amarillo, Texas.

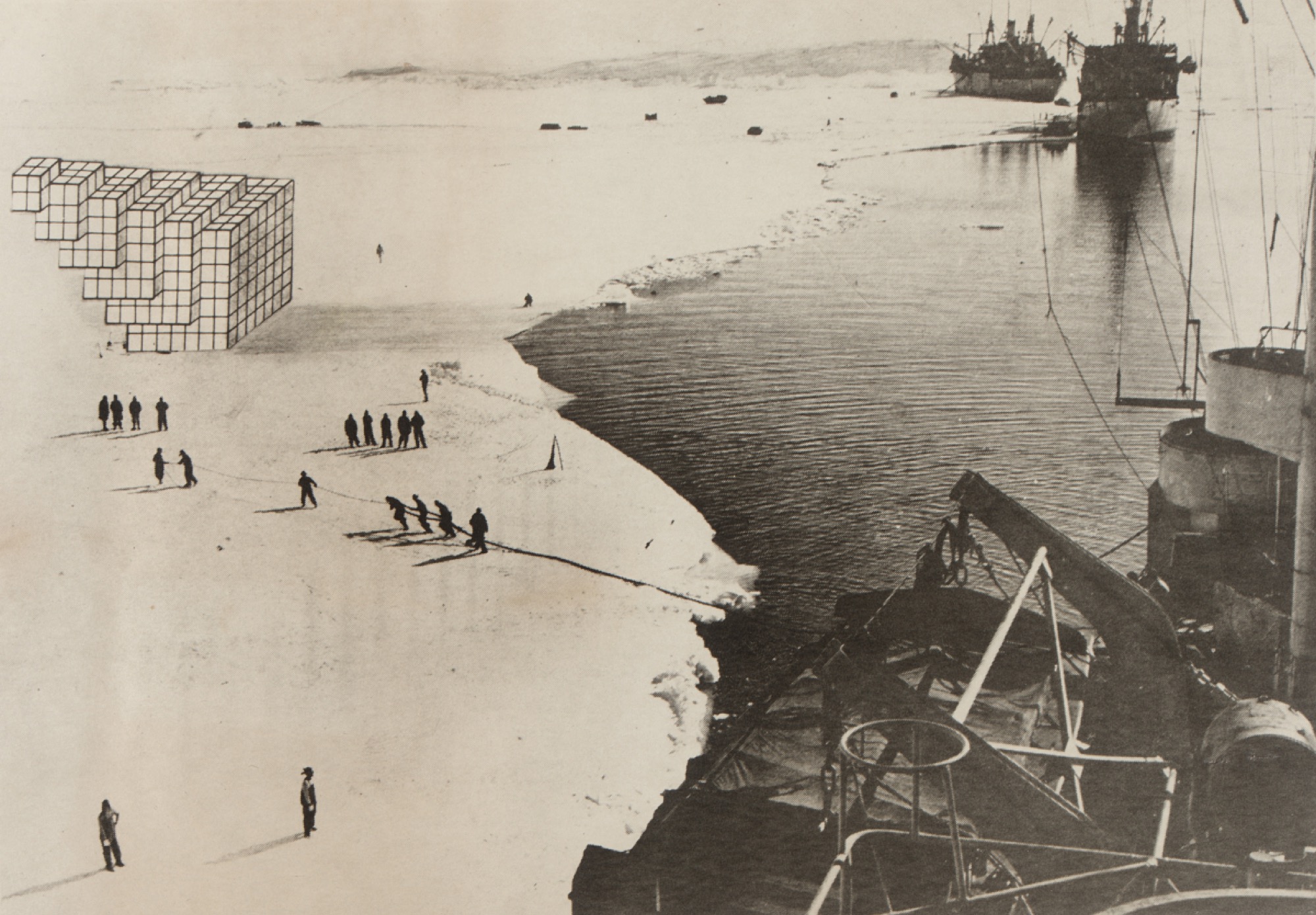

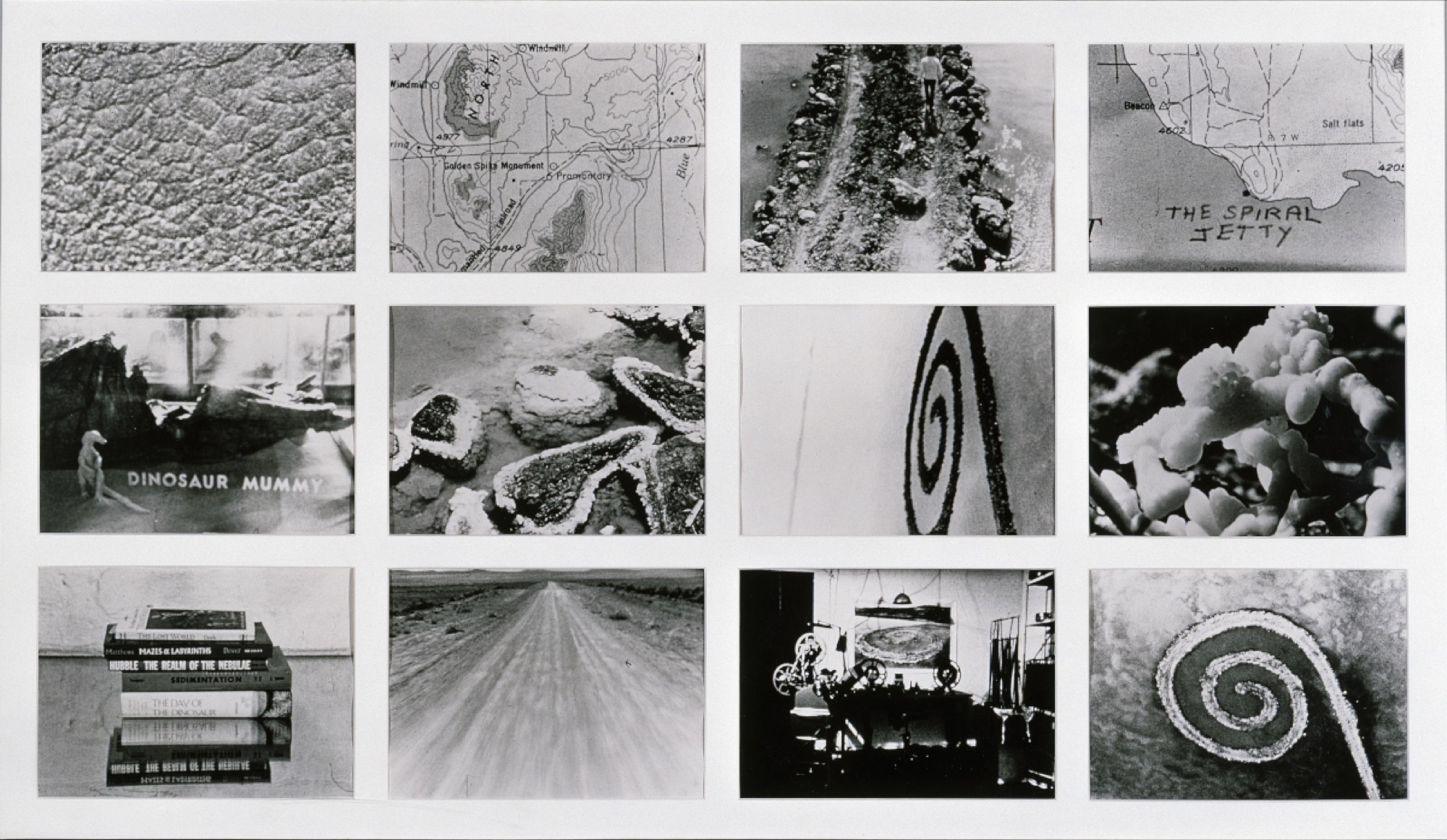

With Robert Smithson: Time Crystals, now on display at MUMA after being shown at the University of Queensland Art Museum, curators Amelia Barikin and Chris McAuliffe have not simply put together a celebration of Smithson. Rather, they present something of a rarity in the Australian exhibition context—a modestly sized retrospective of a major international artist, curated by locals, that proposes a distinct interpretation of the artist’s work, or at least tries to bring to light something about it that they feel has not been sufficiently recognised. In this instance, this is not a focus on a lesser known period in Smithson’s body of work (in the way, for instance, that a 1985 exhibition of Smithson’s early religious painting sought to recalibrate understanding of the artist’s relationship to his minimalist peers), but rather a subtle shift in conceptual framing, concerning the interpretation of Smithson’s ideas on temporality. As Barikin and McAuliffe note in the wide-ranging essay published in the exhibition catalogue, Smithson’s engagement with notions of temporality is ‘most frequently associated with entropy—the gradual disintegration of all matter into a state of elementary chaos over time’. This anti-humanistic, not to say nihilistic, image of the fate of all things, pictured on an enlarged geological time-scale, is enacted in major Smithson works such as Asphalt Rundown (1969), in which a dump truck poured a load of asphalt down the walls of a quarry on the outskirts of Rome, and in his acknowledged masterpiece, Spiral Jetty (1970), the enormous structure built from 6,500 tons of basalt and earth in Utah’s Great Salt Lake that was destined to disappear for many years beneath the surface of the lake, only to remerge entirely covered in white salt crystals. Barikin and McAuliffe argue that the notion of entropy does not exhaust Smithson’s thinking on time, pointing to a recurring logic throughout Smithson’s writing and work that, using a phrase from the artist, they call the ‘time-crystal’, a sort of frozen timelessness within temporality itself.

I will return to Barikin and McAuliffe’s interpretation of Smithson’s thoughts about temporality, which are presented more strongly through their essay and the accompanying wall text than in the works displayed in the show. Turning to the exhibition itself, we find a small but powerful selection of pieces from 1965 onwards—the moment in Smithson’s career when he began to engage with the sleek industrial aesthetics of contemporary sculpture and, in his words, ‘became a conscious artist’. In Enatiomorphic Chambers (1965), mirrors are placed within two steel structures to create an uncanny optical effect in which one sees a view of the surroundings absent of one’s own reflection. The dematerialisation effected by these somewhat clunky steel sculptures allows us to experience what Anne Wagner has eloquently described as Smithson’s tendency to wring ‘immaterial effects and sensations from materials that are almost hyperbolically present, insistently there’.

Although it is a pity that the Monash exhibition doesn’t include Rocks and Mirror Square II (1971), shown in the Queensland iteration—which piles basalt rocks against their intangible mirrored doubles, acting as a beautiful illustration of Wagner’s observation—we do get the Yucatan Mirror Displacements (1-9) (1969), a magnificent series of photographs documenting arrangement of mirrors in various rural locations in Mexico. Placed in roughly geometric patterns in landscapes of lush forest, deep red dirt, and pale sand, the mirrors generate temporary works of a sort of real-world cubism (perhaps more of the Juan Gris variety than that of Picasso and Braque). External reality is fragmented into a series of shimmering, discontinuous planes, while still declaring its materiality; the tactile sits next to the purely visual. Indeed, one could argue that these works reveal a continuity between Smithson’s work and some of the deepest concerns of modernist painting. For isn’t the tension and play between the immateriality of purely visual experience and the material density of the canvas one of the key logics of modernist abstraction?

As the art historian Jennifer Roberts has complained, there has been a tendency to picture Smithson as a radical outsider ‘who seemingly swooped in from his own bizarre world’ to denounce the formalist modernism dominant in the early 1960s. Smithson’s own writing encouraged a view of his work and ideas as radically opposed to the structures of modernism, a position accepted in Barikin and McAuliffe’s interpretation of his work. But I would caution against any overly clean attempt to quarantine Smithson from the structures and images he inherited from modernism and the avant-garde, no matter how strongly he railed against them. Barikin and McAuliffe repeatedly oppose the ‘progressive logic’ of modernism to Smithson’s negation of historical time. But it is worth remembering the role played by the fantasy of the ‘end of history’ within the most teleological variants of modernist progressivism. Perhaps Smithson’s crystalline image of a frozen temporality is really a variant of the belief, held deeply by all of the major avant-garde movements of the 20th century, that the history of art ends with them? We might also point to the seeming contradiction that exists between the curators’ enthusiastic endorsement of Smithson’s critique of art history modelled as linear progress and the presentation of his work and writings as representing a radical novelty in the context of 1960s art—for what is this radical break but a linear historical movement from one period or style (even if this period or style is understood, in the manner of one brand of postmodernism, as the end of distinctive periods and styles) to the next? More importantly, we might ask just how different the specific notion of Smithsonian temporality that the exhibition argues for—a time of ‘actuality’ opposed to chronometric time—is from modernist critic Michael Fried’s characterisation of the experience of viewing a work of art as existing within a non-temporal ‘presentness’. Rather than seeing them as radically opposed, could we not see these concepts in Smithson and Fried as belonging to the same affective vocabulary, in which moments of qualitatively differentiated intensity are set against the instrumental quantification of experience, represented in this instance by clock time? Even the grandiose anti-humanism of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, of which Thomas Crow has written that it represents a model of art in which ‘humanity (is) no longer the measure, nor even the point, of art’ can be seen to belong to the key romantic modernist category of the sublime. (If in the Kantian sense what is sublime is not actually the sight of the practically infinite expanse of the sea, for example, but rather the experience of our faculties transcending the given order in the idea of infinity, what is more properly sublime than the fantasy that human beings could conceive of an art no longer concerned with humanity?).

Of course, these continuities should not be overemphasised; Smithson’s work is certainly quite outside the norms of 60s formalist modernism, and it is precisely for this reason that he has been so influential on the development of art since the 1970s. Sharply opposed to the evacuation of narrative and conceptual content characteristic of much formalist modernism—expressed most succinctly by Frank Stella’s famous non-explanation that ‘what you see is what you see’—Smithson’s work and his comments on it are packed with references to phenomena outside art, content that often takes shape as series of bizarre associations (such as the manifold instances of otherwise unrelated spiral forms that Smithson’s essay and film on Spiral Jetty brings into the work’s orbit, including, for instance, a connection—whatever exactly it might mean—between the shape of the work and the ‘spiralling’ of the 16mm film on the reel). Art historian Caroline Jones has suggested that it is precisely this ‘dense matrix of meanings’ that accounts for Smithson’s continuing appeal to contemporary practitioners. In presenting the works alongside a multitude of notes, books and papers from the artist’s archive, the Monash exhibition suggests a similar interpretation of Smithson’s legacy, and develops a thought-provoking attempt to unwind the dense tangle of Smithson’s ideas.

But—as heretical as it might sound to Smithson admirers—one wonders at times whether these ideas are perhaps being taken too seriously. One of the finest works in the show is Hotel Palenque (1969-1972), a series of 35mm slides accompanied by audio of a lecture given by Smithson at the University of Utah. In the lecture, Smithson comments for over 40 minutes on a series of photographs he took of a Mexican hotel that fascinated him because it seemed to be decaying at the same rate it was being constructed. Over an endless series of details of the construction site, Smithson delivers a loose, rambling lecture that comically interprets the decay of the building as deliberate, as if it is a relic of some unknown ancient culture. Showing a slide of weeds growing through incompletely built parts of the structure, for example, he explains how the foliage is deliberately given time to grow as an instance of ‘dearchitecturalisation’. Clearly enjoying himself and amusing his audience, he rambles about the ‘subterranean force’ in the Mexican ground and invites quasi-philosophical appreciation of a ‘pile of cement as cement—dig it for its cementness’. The piece becomes a theatrical performance of interpretation and the generation of meaning, one that invites speculation on the ‘dense matrix of meanings’ present in Smithson’s other works. Is the specific content of these references perhaps less important than the very fact that the work is being strung along a discursive and associative chain? Are Smithson’s webs of references perhaps most important simply as gestures of refusal directed against the modernist notion of art as outside of language and discourse (or to put it in less critical terms, as a mark of his longing for those dimensions of art that had been left behind by this version of modernism)? And does this also suggest that, in having its primary importance in its opposition to a non-discursive model of art, Smithson’s ‘matrix of meanings’ is ultimately not the postmodern rupture with autonomous art it is made out to be, but still, unavoidably, ‘art about art’?

Francis Plagne is a writer and musician from Melbourne.