Robert Hunter

David Homewood

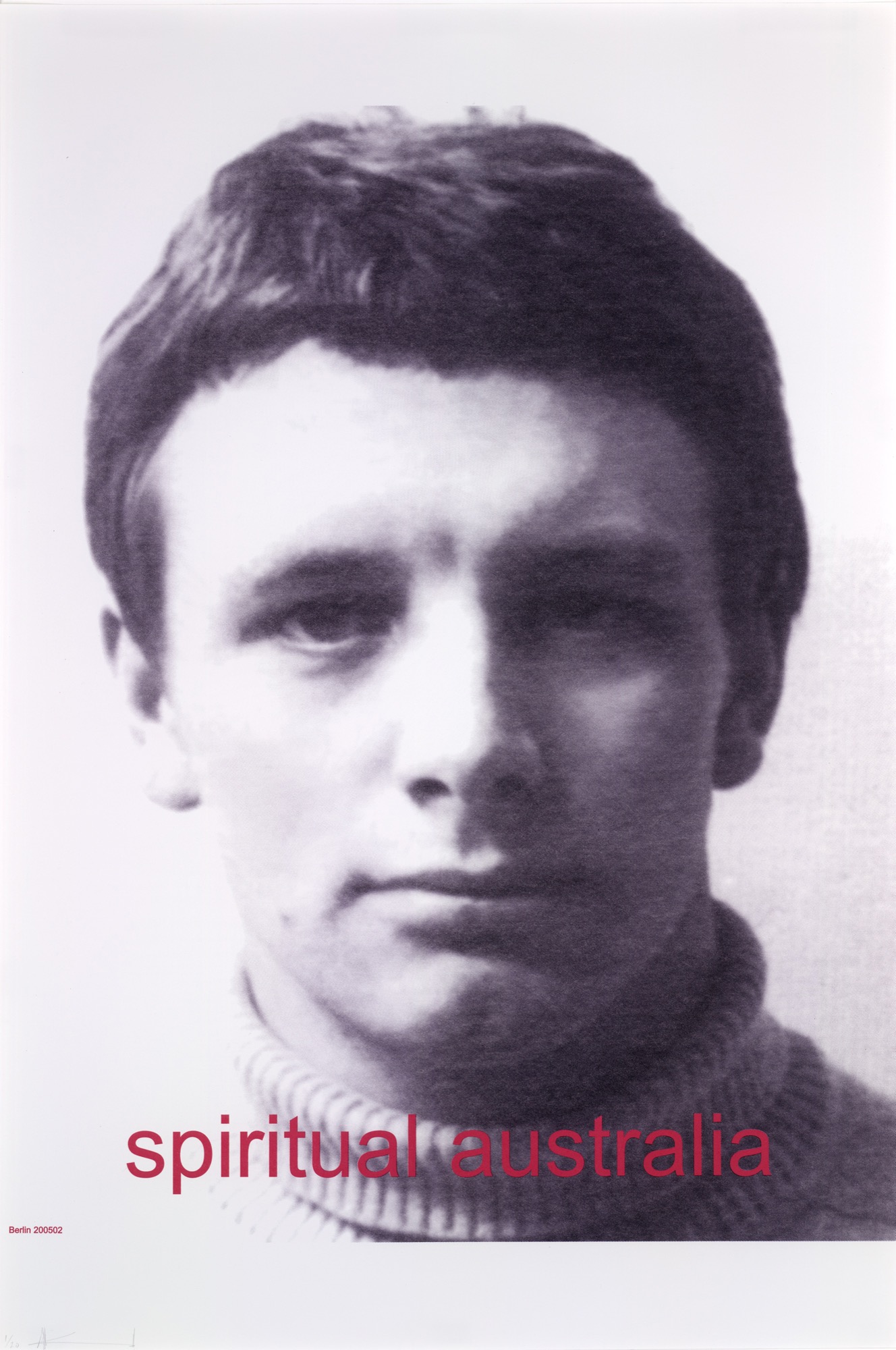

His hair is brushed forward in a modish style that matches with his woollen turtleneck jumper. He stares into the camera lens with an expression that is difficult to describe—neutral, serious, handsome, vacant, boyish, bewildered; it is not quite any of these. When this photograph of the twenty-one-year-old Robert Hunter appeared in the catalogue for The Field, the 1968 exhibition that inaugurated the National Gallery of Victoria’s St Kilda Road premises, it was not accompanied by any images of his artwork. This absence was due, the catalogue explains, to the photographically unreproducible interplay of whites and off-whites in Hunter’s work. Immediately, The Field was identified as a key episode in the history of modernism in Australia, and the near invisibility of its youngest contributor’s artwork was part of its narrative.

The exhibition, simultaneously, inscribed itself in the story of Hunter’s art. It launched him onto the national stage, introducing his art to a wider audience. But the full significance of The Field to Hunter’s art would become clear only later. For the next forty-five years, Hunter persisted with the same aesthetic agenda—Hunter’s friend and fellow Field participant Robert Rooney once called him a ‘one-idea artist’—that had guided his contribution to the 1968 exhibition. While the work of other artists in The Field evolved, Hunter stuck to his distinctive brand of ghostly minimalism. This ghostliness arose from the visual liminality of Hunter’s art, but also, perhaps, from the lingering presence in his art of The Field, in the form of a memory or after-image. The artist’s image, furthermore, continues to be identified with the exhibition, as seen in a 2002 screen-print by Scott Redford featuring a blown-up reproduction of Hunter’s Field portrait accompanied by the words ‘spiritual australia’ in pink Helvetica. Hunter’s place in the national art-historical imagination is contingent, it would seem, on his status as the poster-boy for the so-called ‘Field generation’.

The historical entwinement of Hunter and The Field provided the rationale for the National Gallery of Victoria’s programming of Robert Hunter, a retrospective exhibition curated by Jane Devery, concurrently with The Field Revisited, a restaging of the 1968 exhibition. The exhibitions were entirely different in tone. The Field Revisited was a glittering exercise in institutional self-aggrandisement, an attempt by the museum to broadcast its historical significance through restaging the watershed exhibition half a century on. (Some argued that the original was a provincial imitation of overseas art; a similar criticism could be targeted at the sequel for its dull reliance on the well-worn strategy of remake, a staple of contemporary curation). Hunter’s exhibition, by contrast, was without fanfare. The exhibition was chronologically ordered, consisting of paintings and some archival materials, and was supported throughout by informative wall texts. As such, it was an unprecedented opportunity to appreciate the breadth and scope of this artist’s aesthetic achievement. The exhibition was also an opportunity to reflect on questions provoked by his work, and the mythology that has grown up around it. What does Hunter’s art represent now?

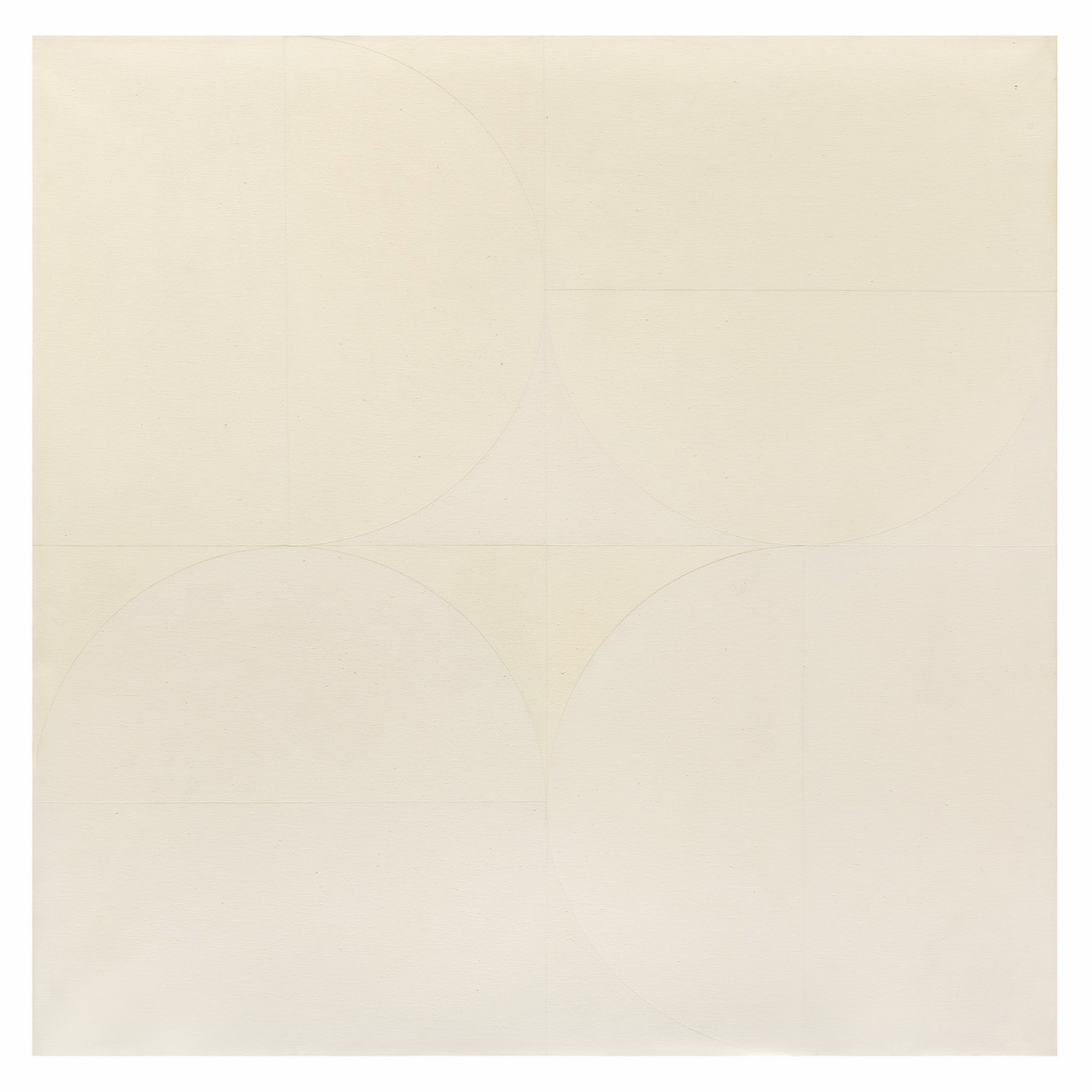

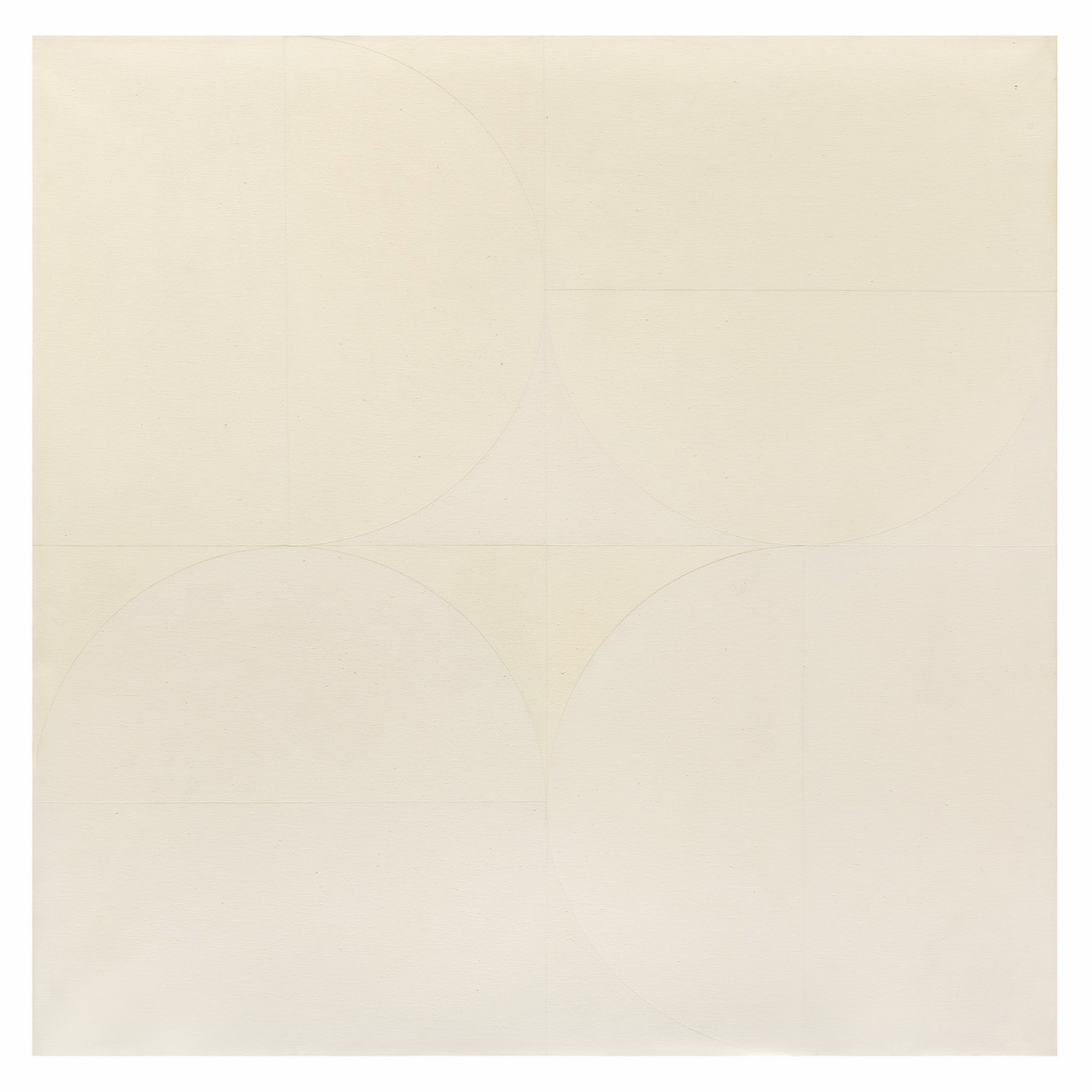

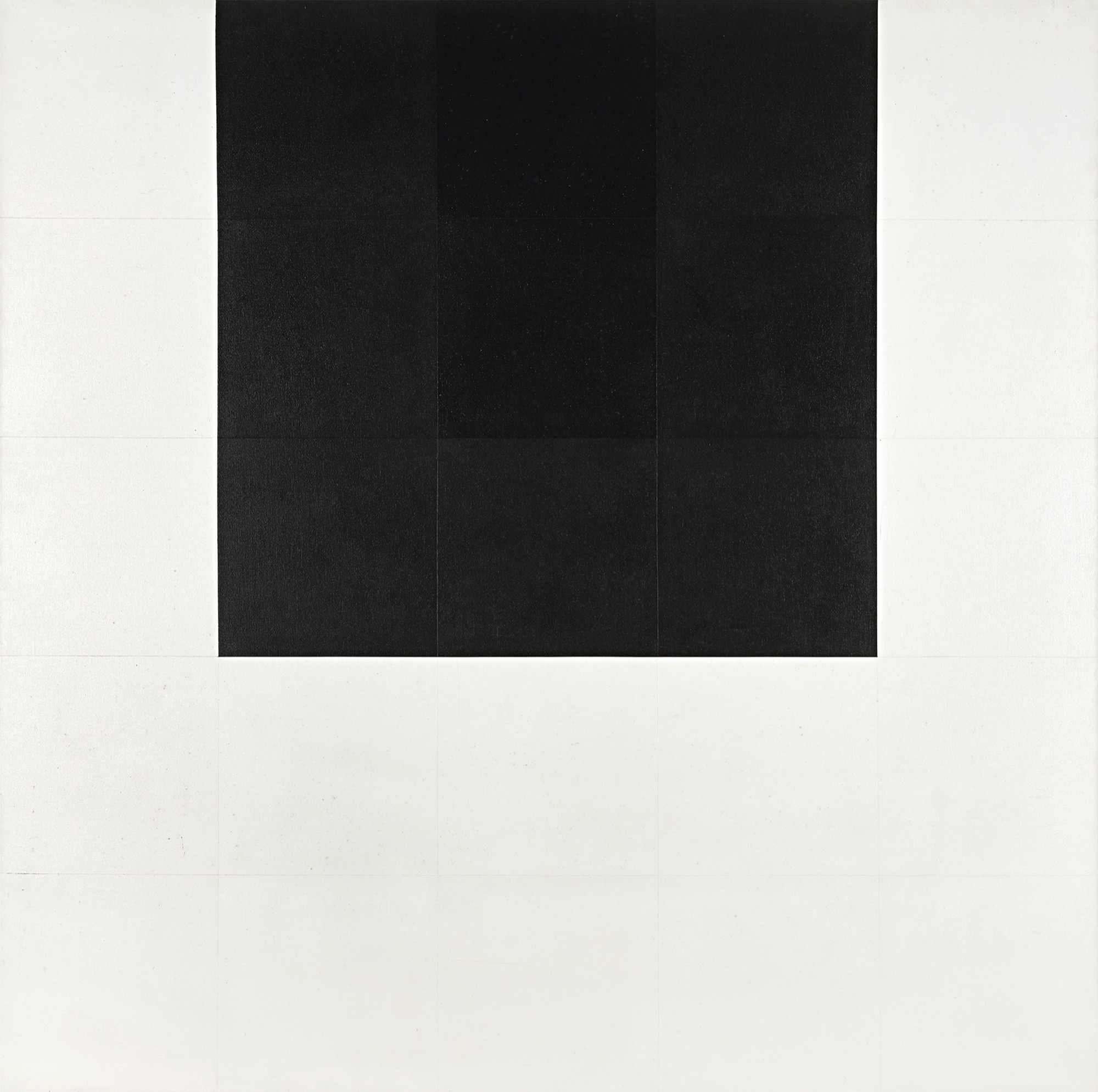

Hunter’s reticence when talking about his art is legendary. He did not talk much about his art; however, on the few recorded occasions that he did, one of his recurring claims was that when he worked, he was ‘doing the same thing all the time’. He said that his career ‘had been like painting one house over and over’, and that all of his paintings ‘dated back to the first idea’. The retrospective opened with that ‘first idea’: a selection of works from his debut solo show at Tolarno Galleries in May 1968. These eight luminous canvases showed the twenty-one-year-old Hunter as already at the height of his powers. Similar to the ‘black paintings’ by Ad Reinhardt that he had encountered the previous year at a MoMA travelling show at the NGV, the geometric systems and chromatic arrangements of Hunter’s ‘white paintings’ emerged only through prolonged looking. Close inspection of each picture surface revealed raised lines in the intervals between neighbouring forms, the build-up of numerous coats of thin Dulux house paint layered onto cheap cotton duck, impregnating these otherwise flat designs with a discreet sculptural dimension that further enhanced their subtle perceptual effects.

Bearing the influence of Hunter’s intermittent employment as a housepainter and builder’s labourer, the core elements of his 1968 paintings—reductive composition, muted colour, workmanlike application, domestic materiality and serial method—came to form the basis of his subsequent enterprise. What came next, though, was hardly as monotonous as Hunter made it out to be. Presented across four rooms that together comprised the first half of the exhibition, the opening one and a half decades of Hunter’s career were shown to be marked by a series of painterly inventions and negations in dialogue with the latest avant-garde styles, from hard-edge painting through minimal, post-minimal, and conceptual art, driven at all times by a strong sense of experimental progression.

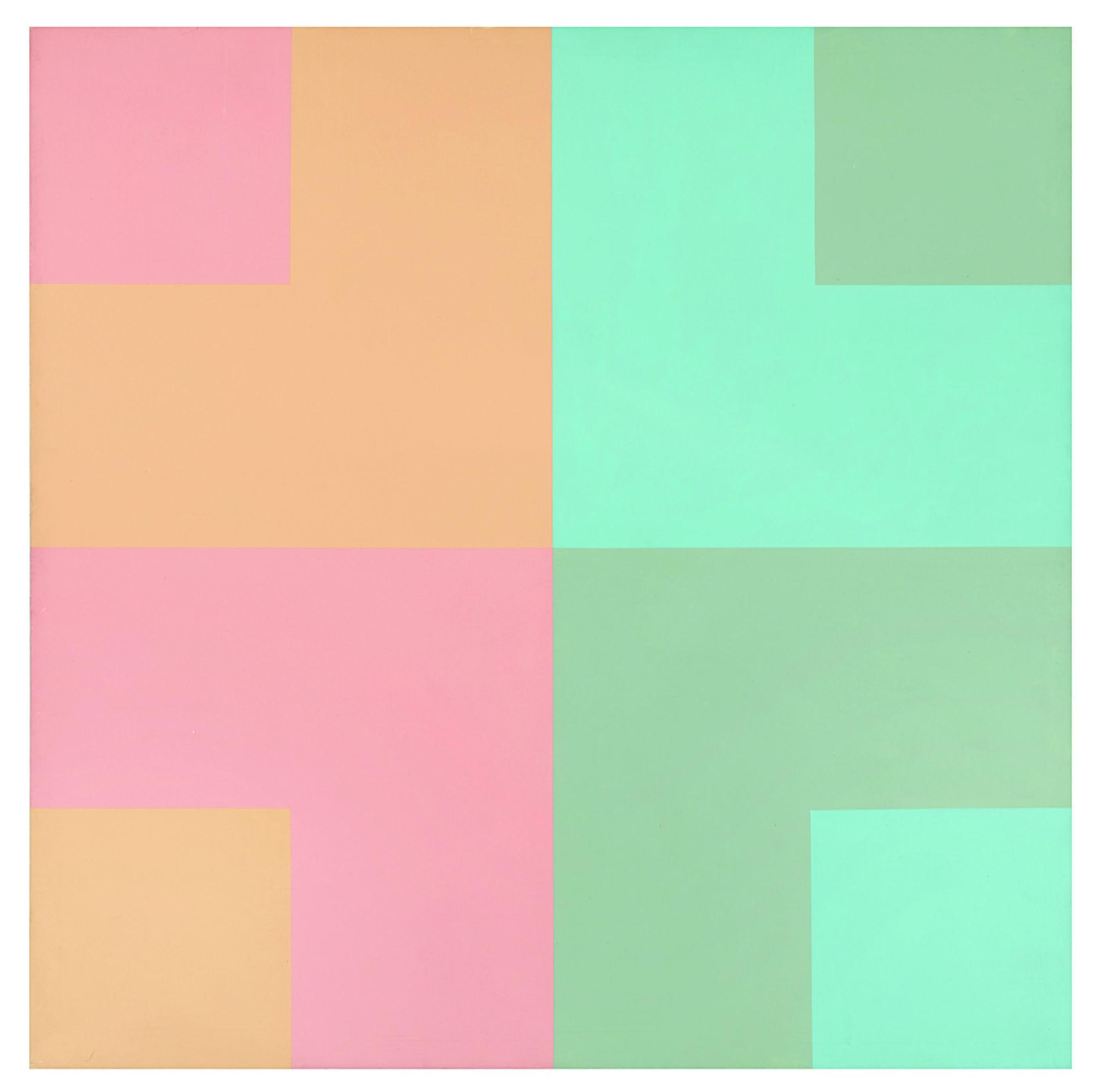

At one end of a long corridor leading on from the partial Tolarno re-hang was a pastel-coloured cross painting of 1966, one of the nineteen-year-old Hunter’s initial forays into hard-edge abstraction and the earliest work included in the show. Painted the year before ‘the new abstraction’ captured the imagination of a new generation of Melbourne artists, including Peter Booth, James Doolin, Dale Hickey, Robert Jacks, Ti Parks, Rooney and Trevor Vickers, Hunter’s cross painting emanated a youthful commitment to modernism. The placement of the cross painting adjacent to the white paintings powerfully drew out the compositional and chromatic affinities between them, and demonstrated that the systematic character of Hunter’s abstractions pre-existed his breakthrough Tolarno works. This ‘early work’ confirmed that Hunter was an unusual type of artist—one who emerged, as it were, fully formed—for whom the typical categories of early, middle and late do not really apply.

Yet unaccompanied by any other work from 1966 or 1967, the cross painting looked out of place. Tacked onto the show as a cursory acknowledgement that the origin of Hunter’s enterprise predated the white paintings, the solitary presentation of the cross was also symptomatic of a curatorial desire not to draw too much attention to this phase of his work. One expected that a small room be dedicated to more of Hunter’s little-known early abstractions from the mid-1960s, possibly alongside a selection of his even less-known figurative expressionist canvases, one of which the young Melbourne critic Patrick McCaughey awarded first prize at the Eltham Art Prize in 1966. The inclusion of more mid-1960s paintings might have contradicted the story that Hunter’s work conformed from the outset to an overarching system (this, perhaps, is the reason for the absence of these works), but their inclusion would have added diversity and texture to the show; instead, it constructed a simplified, incomplete account of Hunter’s work of the 1960s.

In the corridor, the least successful area of the exhibition, the cross painting was hung with three other works or groups of works: four black and white paintings from 1969, a remake of Hunter’s first wall painting from 1970 and a grey painting from 1977. With the earliest and latest works in the first half of the exhibition hung at either end, the corridor was meant as a transitional space that would prompt the spectator to wander around the adjoining rooms in search of answers to the formal transformations that unfolded in Hunter’s art during the intervening period. But it appeared as a heavy-handed spatial metaphor for the passage of time, hurrying the unsuspecting spectator through half the artist’s oeuvre—an arrangement that was at odds with the slow, intricate, additive, and repetitive temporality of Hunter’s art. Aesthetically, the corridor juxtaposition of paintings from different periods, of different palettes, of different materials, was just plain incongruous. The pastel cross, for example, was unfortunately paired with the wall painting. The one was a garish early attempt at hard-edge painting, the other a ghostly row of modular grey lattice patterns from a later moment dominated by avant-gardist claims that traditional mediums were ‘outmoded’ or ‘obsolete’ – defined, in other words, not by the utopian promise of painting but the threat of its imminent disappearance. The contrast was mutually deflating.

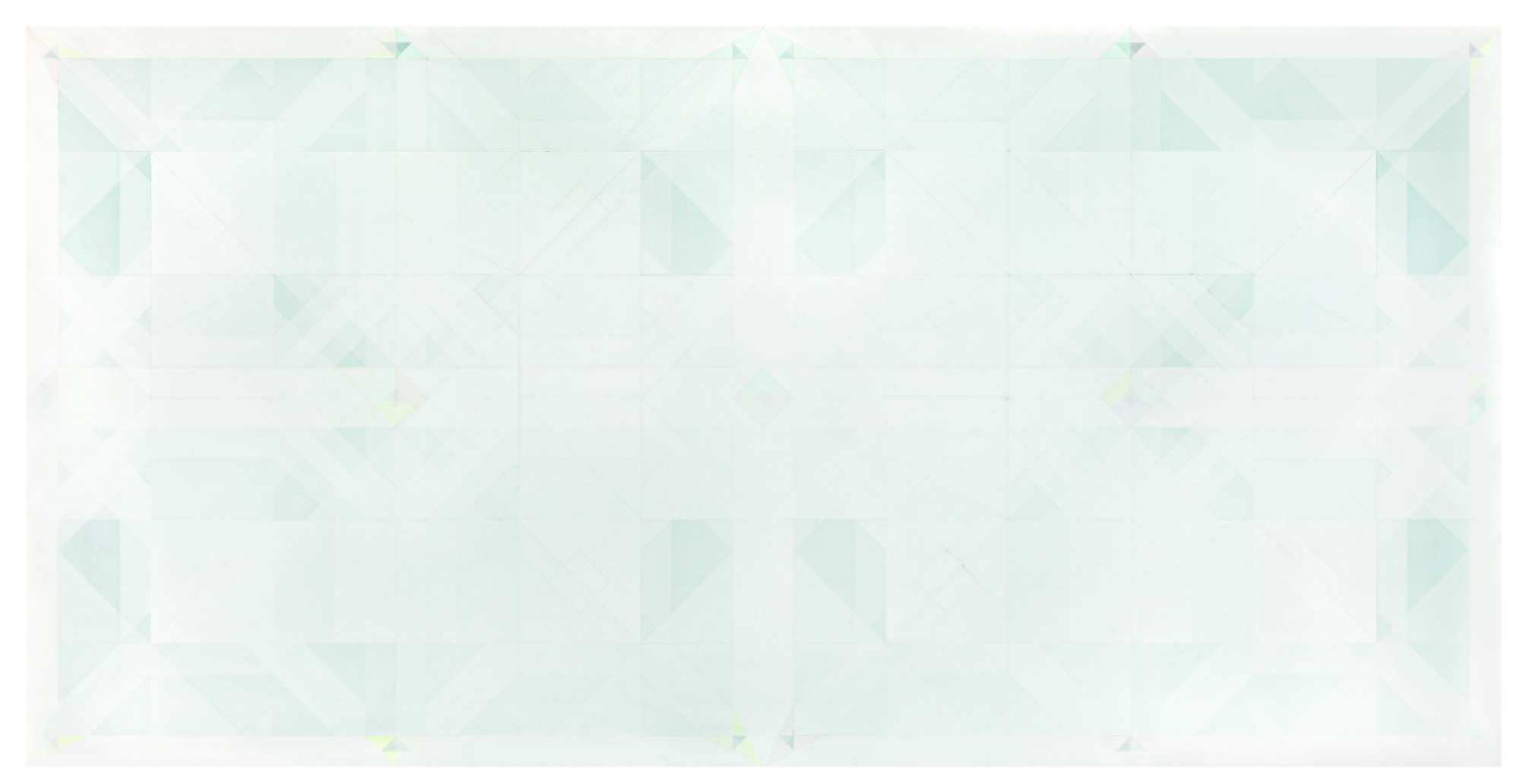

The wall painting, hindered by its appearance too early in the exhibition, was further compromised by the physical dimensions of the corridor. The repetition of the geometric design along the wall expressed a minimalist desire to eliminate technical virtuosity and traditional artistic materials as well as to activate the literal relationship between artwork, spectator and architecture. When it was first exhibited at Pinacotheca, Richmond, in July 1970, however, the literalness of Hunter’s painting was overshadowed by its residual illusionism. Critic Ann Galbally observed that the painting appeared to hover in front of the wall; another critic, RG Lansell, described the patterns as ‘phantom murals’. Hunter’s transgression of literalist minimalism is doubtless one of the intriguing aspects of this work; however, reports of the otherworldliness of the original piece might have seemed far-fetched to those who encountered the work at the retrospective yet saw no shimmer of illusionism.

The reason for this was not due to any technical or material deficiency in the remake. Like the original, it was made by pinning a homemade masking tape stencil to the wall then rolling on two tones of watery grey paint, shifting the stencil along and repeating the process. But at the NGV, the irregularities within and between the ‘shadowy oblongs’, as they were referred to by Lansell, did not generate a comparable optical effect. This was because the illusionism of the original was contingent on the cavernous architecture of Pinacotheca, which allowed the painting to be viewed from a sufficient distance for the painterliness of the work to dematerialise into a spectral image flickering on the empty wall. The impact of the 1970 original, furthermore, was presumably enhanced by its presentation in the factory-turned-gallery, accompanied only by the palpable absence of neighbouring artworks. In the NGV retrospective, the situation was different. The illusionism of the painting was cancelled by the narrow corridor, reducing the work to inconsequential decoration; meanwhile, the four magnificent canvases on the wall opposite usurped whatever fragile presence the wall work may otherwise have had.

Most visitors probably would not have noticed the wall painting because, mesmerised by those four paintings opposite, they would have had their backs to it. Painted in 1969, these four works were based on a series of generic compositional manoeuvres—a black cross dividing the picture into four smaller white squares, the horizontal division of the canvas into two or four sections of black and white. The paintings promoted their objecthood (their physical, literal properties) with an intensity that is associated with minimalists such as Jo Baer or Richard Serra. They showed Hunter refining his stock-in-trade, stamping out the lingering chroma of the white paintings and hardening his earlier asymmetries into bold right-angled designs of black and white. Another aspect of these paintings was their intricate facture. Unlike earlier works, where raised lines delineated the edges of shapes, a more complex network of lines now formed a second pattern that coincided with but also remained distinct from the flat design below, deepening Hunter’s assertion of painting’s material ground.

The patterned picture surface was a sign of the tedious technical process that brought it into being, and as such foregrounded the labour-time of the painting subject. The presence of this subject was palpable in two 1970 works hung in a room to the left of the corridor, which flouted the mathematical exactitude of hard-edge abstraction. In a grey work reminiscent of Agnes Martin, a painter who famously spoke of painting ‘with my back to the world’—not a bad characterisation of Hunter’s relationship to the same medium—a matrix of cotton thread was overlaid with a hand-drawn diagonal grid; its shakiness was an intimate reminder of the artist’s hand guiding the pencil over the canvas. The neighbouring work, a six-part modular paper painting, was made by taping small, rectangular pieces of paper into large, flimsy picture supports, which were then treated with several washes of grey paint. The considerable variation resulting from Hunter’s improvisation within a rule-governed compositional system carried the memory—at once intimate and anonymous—of the painter at work.

These two classics of Australian post-minimalism were presented in a room dedicated to Hunter’s ‘grey period’, accompanied by a wall piece from 1976 and a narrow landscape-oriented work from 1981. This time, perhaps due to the familial resemblance between the paintings and the spaciousness of the hang, Devery’s curation of works from across a large timespan (more than a quarter of Hunter’s oeuvre) paid off. More than the corridor hang, this room powerfully evoked the odd temporality—at once linear and labyrinthine—of Hunter’s art. It did this by making visible the recurrence of particular strategies and devices within Hunter’s work of the 1970s and 1980s, a period that saw him expand his material inventory and technical repertoire.

During this period, the formal element of line remained integral to Hunter’s pictorial conception, and he tested various technologies for line-making: from taped-off paint, to cotton thread, to masking tape. Another attribute shared by three of the four grey paintings in this room was the presence of two overlaid grids, an upright and a diagonal: in the Martin-like painting, this criss-crossing framework was articulated in lines of thread and pencil; in the elongated rectangular painting, the line was made by thread alone. The three-part wall painting, for its part, presented a step-by-step integration of the upright and the diagonal: the first frame, a quadrisected square; the second, a square with a pair of diagonal lines through it; the third frame was the same as the second, except with two additional diagonals running in the opposite direction, forming a diamond within the square. Another of Hunter’s ongoing preoccupations was with discreet colouration. Pink tape lines and primary-coloured threads distinguish his work from British painter Alan Charlton’s belated, dreary grey monochromes. This roomful of grey paintings showed that through time, Hunter’s combination and recombination of seemingly anonymous painterly procedures increasingly functioned as a vehicle for, as Charles Green has argued, the ‘persistence of subjectivity’. Painting was, for Hunter, a medium for the assertion of selfhood and expression, albeit muted to the point of indiscernibility.

Between 1970 and 1976, Hunter’s aesthetic output consisted exclusively of ephemeral wall paintings. It was due to inadequate documentation of these works, the visitor was informed, that only two were remade for the show. This significant gap, which included pieces executed in MoMA in New York, Konrad Fischer Gallery in Dusseldorf and Lisson Gallery in London, was compensated for by a cramped alcove space with two vitrines of photographs and printed matter documenting several wall paintings. This fascinating archival presentation, which also included an audio recording of oral historian Hazel de Berg’s 1969 interview with Hunter (his earliest artist statement), and images of Hunter’s 1978 exhibitions in Melbourne, Newcastle and Brisbane with New York minimalist Carl Andre (the pair met at the New Delhi Triennial in 1971 and stayed in contact), added enlivening contrast to what was otherwise a good, old-fashioned exhibition of paintings. Partly due to the expiry of Hunter’s 1970s wall paintings, the photographs—black and white or sepia-tinged, poorly framed and awkwardly cropped—have now accrued an aura of their own, strong enough to rival the resurrected wall works in the adjacent galleries.

Additional images of the elusive artist would perhaps have further enhanced the archival display, complementing the blankness and impersonality of his paintings. Hunter’s unwillingness to discuss his paintings, his desire for them to be viewed as independent from his thoughts and feelings, has had a surprising consequence: Hunter’s silence only intensifies critical focus on his biography. Indeed, facts about the artist’s life—his coming of age in Eltham; his experience as a house-painter; his formative trip to New York in 1968–69; his love of pool, the cue-sport; even his love of spearfishing—have been called on as clues to the meaning of his obdurately non-representational work. This being the case, the inclusion of further images of the artist in this exhibition would have expanded existing knowledge of his biography, and in turn opened new possibilities for interpreting his work. Such thoughts lead onto a further question: how do some biographical events or personality traits become meaningful ways to interpret a given artist’s work, whereas others remain at the level of gossip or rumour?

Despite Hunter’s repeated claims that all he did was repeat the same painting, the first half of the retrospective proved that there was considerable variation across his work from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s. The back half of the show, a survey of twenty-two works painted on eight-by-four-foot plywood boards between 1983 and 2013, activated the same dialectic of difference and repetition within a more restricted terrain. The presentation of this second body of work within one large space powerfully conveyed the singlemindedness of the artist’s enterprise during the thirty-year period. Each painting used the same method, the same format, the same paint: house paint was applied with a roller, crisp geometries were achieved with masking tape, eight-by-four boards were routinely divided into four-inch intervals. A glorious spectacle, the large back room also definitively distinguished Devery’s exhibition from Hunter’s 1989 mid-career retrospective at Monash University Gallery, Robert Hunter: Paintings 1966–1988, curated by Jenepher Duncan, with which it otherwise inevitably overlapped in its treatment of Hunter’s earlier work.

Devery’s chronological presentation of works, clockwise around the outer wall of the room and continuing across two freestanding walls at its centre, afforded visitors the simple pleasure of watching the evolution (or stasis) of Hunter’s art over this extended period. The spiralling, linear procession conveyed both the additive nature of Hunter’s practice and the vertiginous emptiness to which it gave form. The installation permitted several phases or groups to be identified: the blueish 1985 paintings, featuring rows of basic geometric forms and central, overlaid diamond forms; the 1987 paintings edged with dark blue horizontal bands, their fin-like shapes suggesting clockwise rotating movement around the edge of the painting, the rotation of the fins or blades around the top and bottom edges suggesting movement, the whirring of the engine of production, as one work calls forth the next (an allegory of Hunter’s method?); the warm white ornamental designs of 1991, their intricate dispersion reminiscent of a Persian rug.

There was a noticeable decline in quality in Hunter’s painting after the early 2000s. His work was increasingly dominated by small diagonal crosses comprised of triangular slithers of colour: pastel, initially, then growing more colourful as the decade wore on. Symmetrically dotted around the paintings, these diagonal crosses chromatically punctuated the white and off-white picture fields in which they were embedded. Despite their relative vibrancy, these late paintings paled in comparison to Hunter’s works from 1983 until the late 1990s, the success of which was bound up with their exclusive use of whites, greys, creams and blues.

As the spectator acclimatised to Hunter’s wide white screens, the differences between them slowly emerged. These differences were primarily compositional; as critic John McDonald wrote in a review of Hunter’s 1987 exhibition at Yuill/Crowley, Sydney, Hunter’s post-1985 paintings had become ‘baroque in their complexity’. Hunter was routinely described as a minimalist, and the seriality of his studio ritual had its roots in a minimalist sensibility. But this compositional complexity constituted a significant departure from the classic morphology of minimalist art. Thus, one of the paintings confronting the viewer as they entered the back room, *Untitled no. 6 (for Carl) (1985), dedicated to Hunter’s old friend Andre, appeared as a farewell as much as a homage to minimalism. Eschewing the simplicity of ‘A B C art’, Hunter’s post-1983 paintings consisted of intricate fields of overlaid and interlocking geometries in various tints of white, along with rotating patterns of matte and gloss. The diaphanous form of the paintings shifted with the light and the position from which they were viewed, but up close they enveloped the spectator. Hovering on the threshold of visibility, Hunter’s rhythmic symmetries sucked the gaze back to the centre of the painting as though into a void.

Although Hunter’s later work deviated from the classic look of minimalism, it closely conformed to Pinacotheca dealer Bruce Pollard’s definition of minimalist painting. In the text for his 1987 exhibition Minimal Art in Australia: A Contemplative Art, which included Hunter’s 1966 pastel cross painting, Pollard observed a commonality among the displayed works: they ‘used various locking-in devices to keep the viewer returning to the basically uninflected central area. The slower the wandering (or scanning) in the central area, the more contemplative is the painting’. Pollard’s prescription of ‘contemplative minimalism’ only partially applied in the case of Hunter’s post-1983 paintings: rather than returning the viewer to an ‘uninflected central area’, Hunter’s delicate symmetries returned to a central point. Nonetheless, in returning the viewer back to that point, Hunter’s paintings perpetuated, even exemplified, the contemplative absorption (or acclimatisation) of the spectator identified by Pollard as the constitutive ingredient of minimalism. Distinct from materialist accounts of minimalism, which emphasise the blurring of ordinary and aesthetic experience, Pinacotheca minimalism was oriented towards the aesthetic transcendence of ordinary experience through the contemplative engagement of the beholder.

Pollard’s contemplative minimalism, with its quasi-religious overtones, is distinct from the materialist discourse around the work of Andre, Donald Judd and Robert Morris, who conceived of art as a field of activity that would occasion ‘interesting’ or ‘neutral’ experiences no different to ordinary experience—a supposedly anti-aesthetic art. The materialism of New York minimalism has dominated historical narratives of the movement; recent revisionist histories, however, indicate that this was merely one minimalism among others. In fact, the contemplative minimalism defined by Pollard has much more in common with the spiritual dimension of Californian minimalism as practised by Robert Irwin, who Hunter befriended in Australia in 1973, as well as John McCracken and James Turrell. Similar to these artists, Hunter’s minimalism was developed against the backdrop of a 1960s counterculture permeated by psychedelic drugs and eastern mysticism, integral to which was the idea that an artwork could occasion a state of ‘heightened awareness’ through its defamiliarising effects, which would shake the spectator out of their unconscious habits and daily routines.

An unfortunate promotional video for the exhibition dramatised the transcendental effects of Hunter’s paintings. The ad opens with a close-up of a young woman staring intently into the lens. Suddenly, she closes her eyes and drops her head; in a matter of seconds, her feet have left the ground and she is gliding through the exhibition to an ambient techno soundtrack, freed from the constraints of time and space. Meant to communicate the rapturous experience occasioned by Hunter’s work, the smooth montage was more likely to be seen as a parody of the idea of contemporary art as a surrogate religion.

The religiosity of Hunter’s paintings was not solely the invention of the NGV’s marketing department, however; it also came from the artist himself. A tinge of mysticism is evident in Hunter’s claims that his paintings spoke to him, told him what to do, or when they were finished. The act of painting, he thought, not only involved the artist surrendering their subjectivity: it also involved the painting taking possession of the painter. Hunter’s story about no. 6, the 1985 work dedicated to Andre, recounted in his last public interview before his death, is exemplary in this regard. While he was working on the painting, Hunter recalled, the fourth of a 200 Gertrude Street residency, for four consecutive days Andre spoke to him through the work-in-progress. On the morning of the fifth day, Hunter stopped at Pinacotheca on his way to the studio, where he was accosted by a Time reporter who requested a comment about Andre’s alleged murder of his wife Ana Mendieta, for which he had been charged four days prior—which was all news to Hunter. Sceptics could dismiss Hunter’s tale as a cynical attempt to use Mendieta’s death in order to mythologise his connection with the legendary Andre. Obviously, Hunter’s narrative cannot be verified, but the fact of its narration reveals that he perceived painting—and that he wanted his painting to be perceived—not only as a channel to the spirit world but also as cosmically linked to the inner sanctum of the New York avant-garde.

The mystical orientation of Hunter’s painting was permeated by worldly realities in other ways, too. The apparition of Andre may have been an auditory hallucination, for example, induced by Hunter’s habitual smoking of marijuana. Unmentioned in critical accounts of his work, this fact is an important puzzle-piece to Hunter’s art. It confirms that for him, as well as others within the late 1960s scene in which he matured, minimalism was less an analytical investigation than a heady, psychedelic practice. Art, drugs and mysticism had the common aim, to paraphrase Huxley, of shaking the user out of the ruts of ordinary perception. Behind his self-flagellating systems and purism, the artist was a faded stoner, whose key to the ‘doors of perception’ was through the imbibement of mind-altering substances. Drug-induced highs and the experiential effects of a painting both served as vehicles of defamiliarisation; smoking a joint or making a painting were oriented to the same goal of transcendence.

The otherworldliness of Hunter’s later abstractions was tempered by a further biographical fact: his love of pool, the cue-sport, evident in the resemblance of his paintings to aerial diagrams of pool tables. These paintings possessed the two-by-one proportions of such tables; in addition, the compositional structures of works such as Untitled no. 6 (for Carl) and Untitled no. 3 (1986) seemed to emphasise the six pocket positions. The pool table allusion has previously been understood as a point of intersection between Hunter’s art and his life. What has not been considered is that this allusion implies that painting itself could be a game. Not unlike the chessboard hanging on Duchamp’s studio wall in 1913, or the mid-1990s Standard paintings, reminiscent of football pitches, by Alan Uglow, a minimalist and a fanatical Chelsea FC supporter, Hunter’s paintings imply a similarity between the pictorial field and a field of play. The painting-as-game analogy extends further: Hunter’s adherence to a standard format is reminiscent of the way that each game of pool (or chess, or indeed bocce, of which the older Hunter was an avid competitor) starts from the same set-up, which then opens a myriad of possibilities (forces and angles, divisions and permutations), before concluding with the completion or abandonment of the artwork or match. This, of course, is not an actual conclusion: it merely compels the set-up to be repeated and the formula to be tried out again.

In his 1986 essay ‘Painting as Model’, Yve-Alain Bois described the history of modernist painting as a continuous game in which a series of matches are played out. The match never exhausts the game, he argued, it merely constitutes another episode or development within it. His argument for the inexhaustibility of modernist painting is a fitting framework through which to understand Hunter’s perseverance with the medium throughout times of its utter unfashionability and alleged obsolescence. His work of the 1960s and 1970s resolutely avoided any sort of direct social, cultural or political comment, yet it remained in dialogue with shifts in avant-garde taste; his work after 1983, on the other hand, conveyed an extreme ambivalence to extrinsic factors. This second body of work thus conveyed an utter disregard for avant-gardist squealing about the end of painting, and in this respect, it pushed Bois’ argument that the history of painting has persisted through an endless series of extinctions and resuscitations to a limit point. Hunter came to reject the idea of painting as an historical activity: the idea that painting is inside history, or should somehow respond to it (this is, strangely enough, a deeply historical, deeply modern idea). It is not that Hunter’s work lost its historical significance; indeed, his status among the elite Australian abstractionists of the late twentieth century was (and is) beyond doubt. Rather, Hunter’s work was freed from history in the sense that his practice unfolded one painting at a time in an endless, ritualistic procession that moved according to its own internal rhythm. Hunter’s later abstractions answered only to the self-referential, self-generative rules of his painterly system. The main appearance of history within Hunter’s insular logic of production was The Field, the apparition that he was unable or unwilling to forget.

In his essay published in the exhibition catalogue, Tom Nicholson identified a further layer of allusiveness in the centrism of Hunter’s designs: the ‘small Y shape’ at the centre of the later works, ‘the most delicately created geometry of the painting, and the most intimate to glean—which Hunter … spoke about as being a vagina’. This observation raises the issue of gender in Hunter’s paintings, which has not been previously considered in any depth. Due to their vaginal iconology, Hunter’s paintings inadvertently appropriate what feminist artists such as Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, as well as influential critic Lucy Lippard, who during her 1975 trip to Melbourne stormed into Pinacotheca and demanded increased representation of women artists, called ‘central core’ imagery: an abstract form that structurally resembles a vagina, which they equated with an essential female visuality, a ‘new visual language’ for women artists that would reclaim and celebrate the female form. Hunter’s appropriation of the vaginal form in 1985, a decade after Lippard’s challenge to Pollard, did nothing to change the problem of the under-representation of women at Pinacotheca. In reality, one could argue that Hunter travestied Lippard’s feminist art utopia through subjecting the essential symbol of the ‘second sex’ to masculinist appropriation. The depiction of the female organ by the male artist alone in his studio—the conjuring of an absence in its absence—was a game he played for himself (and with himself). It was masturbation-for-masturbation’s sake, wanker’s art, even Platonic pornography, an erotic-geometric complex.

In one sense, as Nicholson argues, the vaginal suggestiveness of Hunter’s later abstractions demystifies or secularises his traffic with pure geometry, gives a worldly slant to his monastic routine. Yet the opposite is also true: the figurative suggestion of the sex organ elevates it to the status of a sacred entity, and its repetition embodies a kind of ritual worship. Hunter’s repetition of the vagina, spiritualised through geometry, indicates that his urge to start again with the ‘first painting’ was at bottom a desire to return to the origin of the world. What this meant for Hunter was different to the fleshy solidity of Courbet’s depiction of the vagina in Origin of the World (1866), a work that stands at the origin of modernism. Contemplation of the void in Hunter’s works, by contrast, involved a womb-like immersion in which the distinction between self and other was dissolved, washed away by an oceanic feeling. The void was not an object looked at from a distance, but a condition to be inhabited. In this sense, a depth or interiority existed behind, or upon, Hunter’s flat surfaces.

It is customary when writing about Hunter’s work to establish connections between its formal characteristics, on the one hand, and personal anecdotes and biographical facts about the artist’s life on the other. This raises the inevitable question of how, if at all, the libidinal referentiality of Hunter’s paintings relate to the life of their creator? To ask this question is to plunge into the folklore surrounding the ‘taciturn and detached’ artist; stories and memories conveyed through chatter and gossip, unmentioned in official accounts of his work. The worldly passions of the ‘Great White Hunter’, as Rooney once called him, went beyond the aquatic leisure activities of snorkelling and spearfishing, and into the erotic arena. The sexual athleticism of the young Hunter is the stuff of legend, cropping up continually in the recollections of his friends and associates; the topic of Hunter and sex is occasionally alluded to, in addition, in correspondence during the early days of Pinacotheca.

Perhaps the sexualisation of Hunter’s artwork—as seen in Nicholson’s reinterpretation of Hunter’s ostensibly frigid paintings as vaginas—is merely a redirection of already existing, unofficial, sexualised representations of the artist himself. Such representations have coloured Hunter’s artist-persona since The Field; but it is only now, fifty years on, that they have informed an art-historical reading of his work. Why now? What are the historical conditions that have given rise to this new sexualised reading of Hunter’s paintings? In one sense, the re-examination of Hunter’s biography compelled by the libidinal reading seems in keeping with a cultural zeitgeist permeated by movements such as #metoo and the mainstreaming of ‘call out’ and ‘cancel’ culture, which seek to foster accountability and responsibility by ‘making the private public’. Yet, interestingly, the circumstances surrounding the appearance of the libidinal reading flouted political correctness. An essay authored by a white male artist about the vaginal symbolism of white paintings by another white male artist seems curiously out of step with the sensitivities of art discourse today.

Other events that constellated in and around Hunter’s retrospective further exaggerated its untimeliness. There were repeated references in wall texts and catalogue essays to Andre, yet there was no mention of the ongoing accusations that he murdered his third wife. This was a serious omission, especially given Hunter’s bizarre account of Andre speaking to him through a painting in the aftermath of the alleged crime—a key anecdote missing from the Hunter-Andre narrative constructed in the exhibition. In the current cultural climate, where the mere mention of Andre in an art history lecture is liable to be attacked as complicit with the crime he allegedly committed, this zealous alignment of Hunter with Andre was surprising. The NGV was determined to position Hunter within an international art history, to prove that his significance transcends his national context. The strategy failed: the exhibition’s repeated insistence on Hunter’s international status reinforced the provincial anxiety that it was meant to dispel. In the end, none of these apparent problems were of any consequence. The exhibition transpired without comment or criticism. A new generation had been seduced by the Great White Hunter.

David Homewood is an art writer from Melbourne.