rīvus 23rd Biennale of Sydney

Joel Sherwood Spring

The 23rd Biennale of Sydney titled rīvus is no single stream. It spans across five venues including 330 artworks from eighty-nine participants. I wish to navigate the challenging scope of this exhibition through its inclusion of a few specific and meaningful “objects and non-human beings”, namely the Baaka/Darling, Atrato and Boral rivers. The curatorium leading the Biennale (comprising José Roca, Paschal Daantos Berry, Anna Davis, Hannah Donnell and Talia Linz) describe such inclusions as “a way of entangling multiple voices, listening to other modes of communication and asking unlikely questions”. The presentation of these objects leaves much to be desired, though their inclusion illustrates what is at stake within the frame of rīvus as a whole—the violence of legibility in the effort of coexistence.

rīvus invites several aqueous beings into a dialogue with artists, architects, designers, scientists and communities. The animating link between these bodies of water are the voices of Indigenous knowledge holders and community members advocating for the rights of their ancestors and future generations. Across multiple sites of struggle—globally and within the continent of so-called “Australia”—the “voices” of these rivers are presented through recorded interviews akin to testimonials. Each river is attributed as a participant in the exhibition in reference to international legal precedent set in Aotearoa in 2017 when the Whanganui River was recognised to have legal personhood. This was achieved after the Whanganui iwi fought for their river to be acknowledged as an ancestor since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. Nevertheless, the inclusion and codification of Indigenous perspectives in Western institutions is not without risk.

The notion of evidence has become crucial under the conditions of climate change. One requires evidence to make a political claim to influence environmental policy or political kinds of decision making. There is a fundamental requirement to produce evidence within the context of colonial Australia. Many historical and contemporary environmental harms or violations are not organised by our modes of perception. We often don’t see the results of toxification as poisonous molecules enter biological systems or in the case of drought and flooding until it’s too late. Thus damages must be mediated through the voice of an expert to render them legible in a given forum. Often burden of proof of environmental and societal damages falls upon Indigenous Testimony, by which Sovereign cultures advocate for Country. The impulse felt across the exhibition of rīvus is that water could be the substance that might make these different stories, languages, cultures and claims commensurate to the viewer.

The question of sharing stories between communities and between Indigenous groups and settlers (white and black Australia) is a sensitive, politically fraught and often violent exchange. Artists must decide what stories to share with institutions while communities must also decide what stories they share with tribunals, corporations, governments and legal forums. Interspersed amongst the artworks inside the MCA galleries are objects loaned from the Australian Museum, the most affecting of which is a page that describes this exchange: a record of Dyarubbin / Hawkesbury River place names (1829) transcribed from Darug language holders by Reverand John McGarvie. Depending on how you move through the exhibition at MCA you will arrive at this document at an unusual time/place, between two large rooms on level two. The intention of this is unclear and leaves only questions about the derivative outcomes regarding the norms of conservation and display. Is this document sensitive to sunlight, thus can only be tucked away on its own? Why is something that speaks specifically to the context of Sydney and its history not the first thing you encounter? The storage of these kinds of historical materials is highly controlled within these spaces. As within the court, archives follow strict protocols of containment to ensure objects are not damaged and can provide evidence to particular claims.

Displayed on the same level is the Canowindra Fossil Slab #84, a roughly 360-million-year-old sediment sample cut from Wiradjuri country. This is not an indirect mode of measurement mediated through a voice or surface, rather the thing itself is captured through the materials. Although this gestures to some extended relationality, witnessing a prehistoric ancestor can be read as a comment on the history of this continent through the lens of “deep time”. It is not afforded the kind of reverence you might expect in its presentation. This “fossil” is still presented in purely geological grammars as an object to be narrated. Taken together, these “objects” are displayed with little critical engagement in the violent dominant culture that gives these objects meaning. Both Canowindra Fossil Slab #84 and Dyarubbin / Hawkesbury River place names were “discovered” in the westward expansion across unceded Indigenous lands. In contrast, this affordance is not offered to the circle of “custom sourced stones” that sit as part of Tabita Rezaire’s installation Mamelles Ancestrales (2019) which evoke Sydney sandstone but are not described in this manner. Maybe this points to the very real omission that contemporary art cannot hold the vast meaning of these objects within its tenuous linkages.

In one sense, legibility can be defined as the ability to be read or deciphered but in another sense, it is also the capability of being discovered and understood. Sited within the galleries of the National Art School (NAS) is a series of “counter-maps” crossing various scales and contexts that speak generally to the containment of water through dams and contaminations from industrial run-off. These same principles of containment are felt within the walls of the heritage building of NAS itself—a former gaol built with iconic Sydney sandstone quarried across the Eora Nation. For me this speaks to certain architectural characteristics but moreover it speaks to entrenched social beliefs about how spaces contain, enable and support subjects within settler colonialism. Prisons, dams and the social organisation they facilitate arrived here in 1778 with the First Fleet and the preservation of colonial infrastructures continues to play out violently for Indigenous peoples.

The American environmentalist Aldo Leopold made the statement “we can only be ethical to that which we can see”. We require something that produces visibility of injustice for people to act and intervene. Both Caroline Caycedo’s Yuma, or Land of Friends (2019) and Cian Dayrit’s Blueprint of Dam as Sadistic Moment (2022) use graphical conventions of standard mapping practices built on imposed terms of legibility, forcing compliance through reading and deciphering. Historically and materially linked to structures of colonial domination, both works exemplify how an ability to undermine the objectivity of these depictions is critical in resisting them. Caycedo and Dayrit’s practices work with and in response to marginalised communities to counter-map their physical and cultural landscapes. In doing so, they facilitate critical reflection on colonial and privileged perspectives. Giving name to certain edges opens a discussion around the embedded assumptions of all maps, models and representations. Counter-maps produce compelling images as well as strategic interventions which adapt traditional stories to produce legal and political effects by aesthetic means. On one hand these are maps in the cartographic sense but on the other, they narrate the historical emergence of the landscape.

Dominating the second floor of the NAS Gallery, Yuma, or the Land of Friends is a floor to ceiling wallpaper and mural that depicts the El Quimbo Dam on the Yuma river. The installation brings the body into contact at a scale that allows for multiple readings. Blueprint of Dam as Sadistic Moment is also a traditional tapestry—it is a plan in the way that it spaces out the artists body, however it is more profoundly an intervention that attempts to shape a future action. Holding to account the political actors currently responsible for the industrial development of rural communities in the Philippines, Dayrit makes them and the ramification of their extractive practices legible. These counter-maps are unique multivalent objects that non-Indigenous people will only ever comprehend the very edges of its meaning. The landscape over which the colonial surface is laid is treated like a sacred object—as if it’s the focus of an entire conceptual, legal, religious and ritual system—because it is.

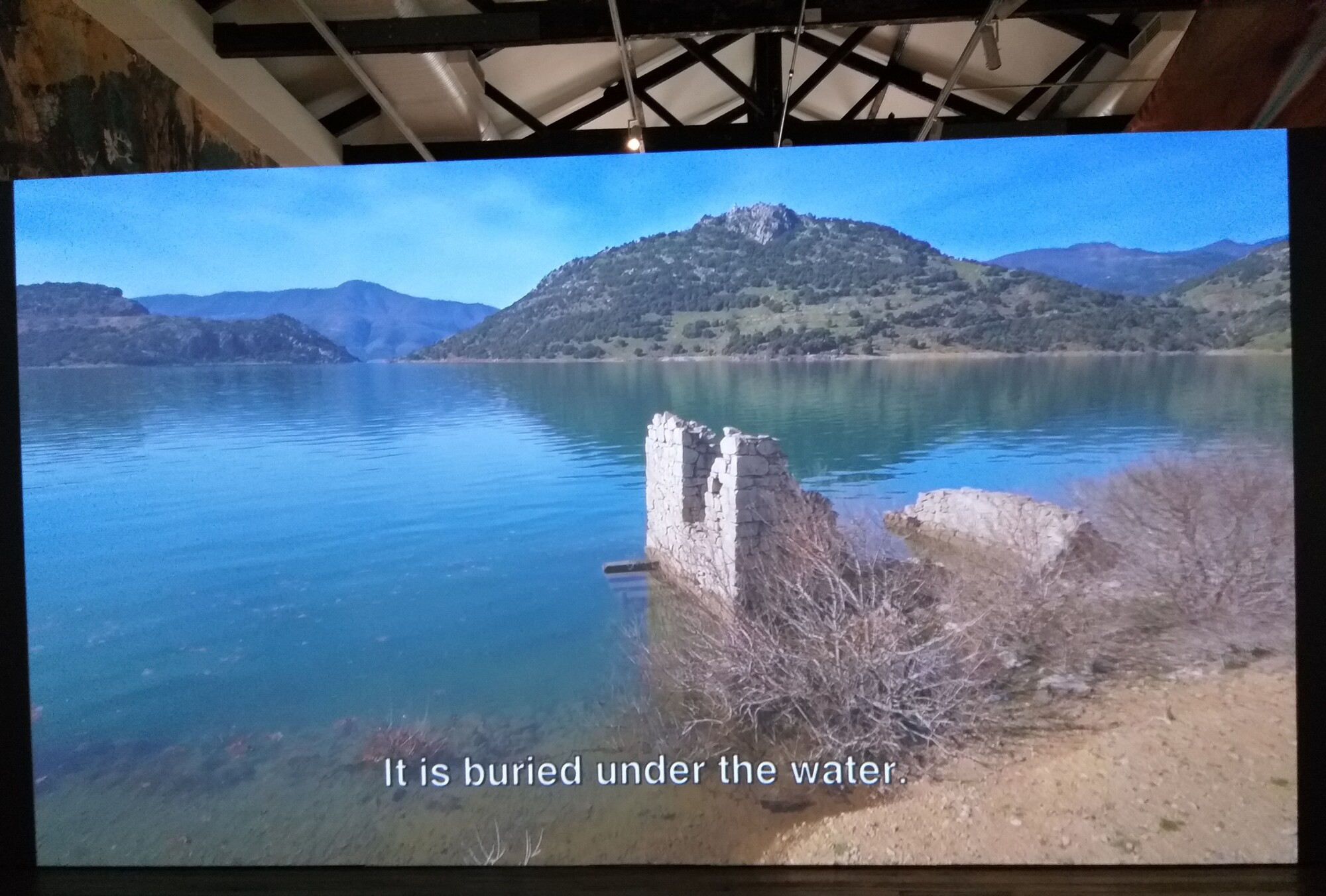

In the adjacent room, in NAS Gallery, Latent Community’s video work NEROMANNA (2019) tells the story of Kallio, a village in Fokida, Greece, from which its inhabitants were evicted in 1969 and later flooded in 1981, being left submerged in an artificial lake. The flooding occurred as a result of the construction of the Mornos dam built to be used as a water reservoir for the city of Athens. This story resonates with Warragamba Dam which was built in 1960 and resulted in the flooding of a large proportion of the cultural heritage and Dreamtime stories of the Gundungurra people. While there is currently an active lobby for Warragamba Dam to be extended, if the dam wall is raised then the remaining sites of this story—including Indigenous archeological sites, creation waterholes and cave art—will be destroyed.

Across all five venues, the curatorial statement printed on plywood boards poses the question “If we recognise them (rivers) as individual beings what might they say?”. Throughout the Biennale and the whole Eastern seaboard the urgency of our current climate crisis is all too clear. It wouldn’t feel right not to acknowledge the devastating floods still at large while I toured the Biennale. The tension or maybe the strength in attempting to bring together the eighty-nine participants is that there is no way to simplify the multitude of experiences or perspectives. What we should realise is that the persons or beings that made each work see the world in a different way and acknowledging those differences, however incommensurable, is a necessary undertaking.

Joel Sherwood Spring is an Artist and educator based on Gadigal Country.