Primavera 2023: Young Australian Artists

Mariam Ella Arcilla

I recently had an oddball dream-within-a-dream where I slept catatonically for five months and missed the Primavera 2023: Young Australian Artists exhibition entirely. The cause of my sleep-in was an alarm clock by my bed that morphed from a twenty-four-hour time-teller into a hypnotic spiral. It twirled its clock-hands back and forth through time, to the point where the Snooze button switched to the word “Overtime.” Then I woke woke up. And today, I’m at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) fighting the urge not to touch the Elmo dolls or wallpaper of flowers at Primavera, just to convince myself that I’m awake, walking in the present.

In her Primavera catalogue essay, Talia Smith, who serves as this year’s curator, evokes a spiral-like concept of time as being distinct from the linearity of Western time. For Smith, who is of Cook Island, Samoan, and Aotearoa/New Zealand European heritage, time is an intertwined continuum that tangles together past, present, and future. She states: “We are always walking alongside our past and future ancestors.”

Hosted annually by the MCA since 1992, Primavera is an exhibition series that spotlights early-career artists from across Australia who are thirty-five years old and under. For its thirty-second iteration, Smith has convened six artists under the thematic trinity of “Protest, Re-imagining, Perseverance,” paying particular emphasis to how ancestral currency is translated through timelines, narratives, and cultures.

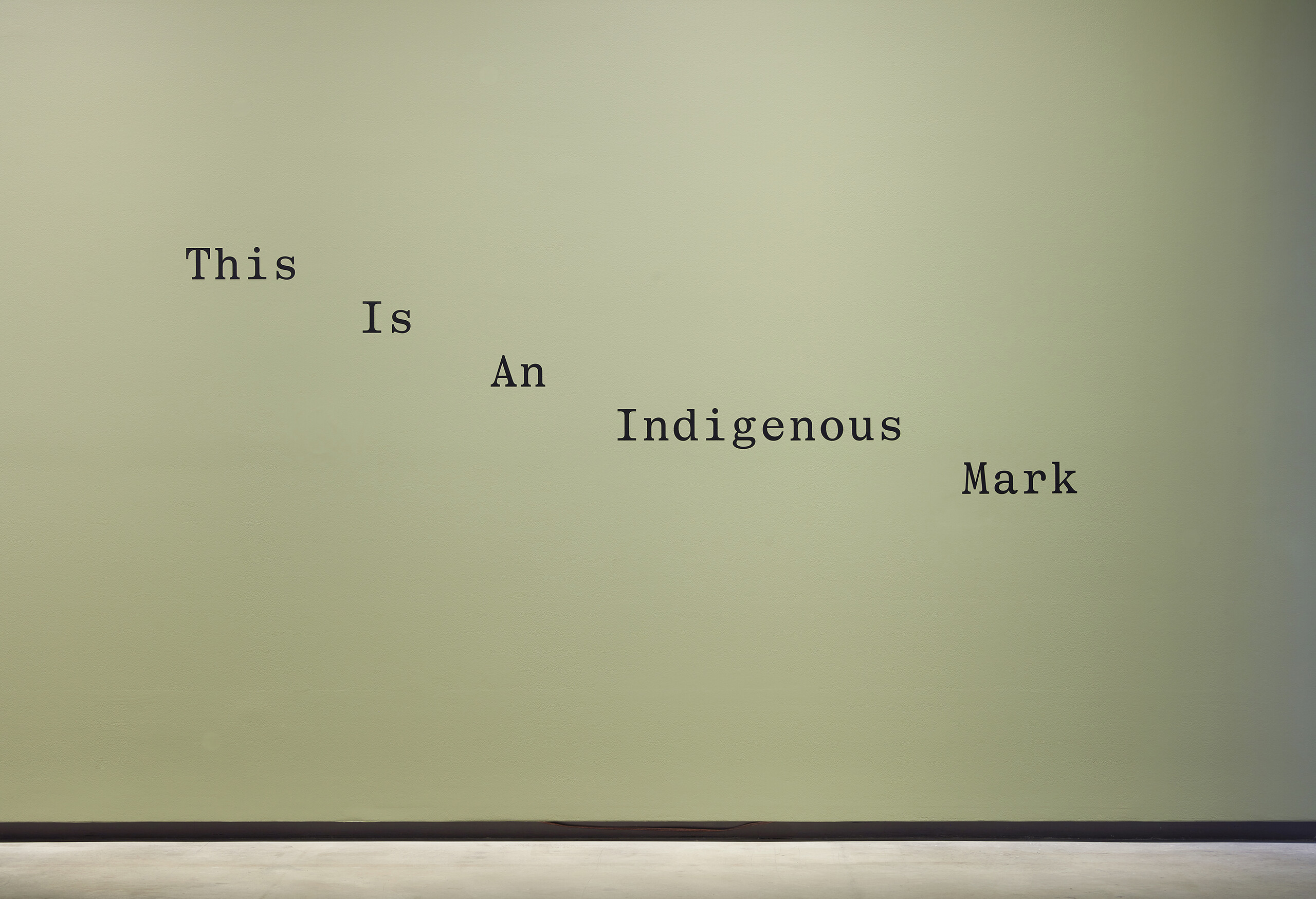

Immediately upon entering the Museum’s Level One gallery, I’m grounded by dapalama (between) (2023), a suite of charcoal marks and vinyl texts by Aboriginal-Italian artist and academic Moorina Bonini that are stamped across the building’s surfaces. Hailing from a matrilineal line of Aboriginal protesters, Naarm/Melbourne-based Bonini foregrounds galleries and academia as her sites for revolt. For Primavera, the Yorta Yorta, Wurundjeri, and Wiradjuri artist uses her body (bawu) and language to question Eurocentric dominance by repositioning Indigenous practices within colonialist spaces, critiquing from within.

On an avocado-green wall is the statement “The western institution is placeless whilst also presenting itself as a fabrication of Place.” The MCA is, of course, one such “western institution.” It is also a site of contested histories: the MCA rests directly on top of the former colonial naval docks used by the British after the First Fleet invasion. The foundational lie of discovering “Australia”—inferred through the uppercase P in Place—is predicated on the violent dispossession of Aboriginal people from 1788 onwards, resulting in the perpetual colonial conquests of Indigenous sites, history, and culture.

Another statement by Bonini, “This Is An Indigenous Mark,” in a spray of uppercase-letters, reminds me of a passage in Jeanine Leane’s chapter from Long History: Deep Time (2015). In it, she refers to the recording—or in this instance, the marking—of a place via a White lens as being shallow-layered, for this timeline is already subsumed by a deep past that rightfully belongs to First Peoples land and memory. As Smith says in her essay, “time becomes selective in Western ideologies: those who hold power continue to do so, if allowed to ignore what has come before.” In “marking” the site, Bonini questions the power dynamics that exist within these institutional structures, and the liberations and limitations that come with them. These vinyl works are elevated by Aboriginal charcoal markings on the lower wall sections. Such markings are used to identify coolamon vessels and shields, and are normally associated with stories of Country and place. In this setting, they appear like barcodes that call us to pay closer attention to how Aboriginal cultural items are scanned, co-opted, and categorised within Western institutions.

My eyes dart back up to the museum windows overlooking Circular Quay, with its litter of sophisticated catamarans and cruise ships. This sparkling vista is paired ironically with Learning how to build a houseboat: walls, fixing and rope (2023), Sarah Poulgrain’s three-part documentation work that sees the artist and their collaborators construct a DIY pontoon boat. A video of Poulgrain assembling steel, aluminium, and rope screens is presented opposite a curvilinear, steel structure representing the boat’s bathroom. Padded by paper pulp, the bathroom’s skeleton is studded by the artist’s hat, ceramic tiles, and videos showing educational lectures about dry toilets and blackwater. Nearby, a coffee-table carries A4 paper scripts by one of Poulgrain’s collaborators, Madeleine Stack. One portion reads: “…nothing is swept away, everything is swept somewhere else. The human error is building things where they don’t belong. It’s a geographical expression of matter out of place…” This makes me think about how the rise of housing and rental costs have driven economically-disadvantaged people to settle into flood-prone areas within Bundjalung nation and Meanjin/Brisbane. Grassroots collectives like Wreckers Artspace in Meanjin/Brisbane (which Poulgrain co-founded), and Lismore’s Elevator ARI come to mind.

Poulgrain’s long-durational project responds to Australia’s socio-economic crisis by transforming the houseboat into a self-sustaining artist-run space and residence—away from the traps of gentrification, real estate, and institutional reliance. It’s a noble approach that flattens the hierarchies of individualism, social stratas, and power hoarding, by privileging reciprocity and collective sustenance. Core to Poulgrain’s work is a circular method of learning and documenting news skills, and then transferring this accrued knowledge to others. By trading skills with interest-specific groups, including ecologists, industrial designers, builders, and leadmakers, Poulgrain is able to foster a collaborative practice grounded by trust, synergetic labour, and relationship building. As the sunlight outside the museum window dwindles, the faint jingle of S Club 7 reaches my ears—the Sydney Harbour party boats have arrived. Cheesy hums of “There ain’t no party like an S Poulgrain party” enter my head as I mentally picture the artist, face obscured by a welding-mask, as a fitting artworld captain.

Malaysian Bidayûh-Anglo artist Tiyan Baker also follows a DIY approach for her installation Personal computer: ramin ntaangan (2022–23). Re-imagining an Indigenous Borneo sanctuary, she combines forest materials like bamboo, palm, and coconut leaf with computer gadgetry to create a traditional Bidayûh longhouse. Inside, a mesmeric screensaver video shows a crocodile rotating on its side. Native to Borneo, crocodiles sometimes feature as wooden totems in traditional homes. The LED lights from Baker’s miniature house splash a fiery-red sheen over the gallery walls, as if it were burning. Perhaps this is a commentary on the eradication of these once-prominent Bidayûh homes to make way for modern, Western-style architecture. This prompts me to Google the word “Bidayûh”—it translates to “inhabitants of land.”

Nearby, a desktop monitor ascends from a green-hilled sculpture, displaying leafy images of Baker’s ancestral home and a black-and-white textbox. It spits out a translative script of Bidayûh-to-English, its puny font-size making it tricky to peruse. I take snaps on my phone camera to zoom into the mantra:

nguleek sanda’, nguleek baba’

Sharpen our speech, sharpen our mouths

tampa’ raja bu’ ai

God, King of crocodiles

tampa’ raja motherboard

God, King of motherboards

Born and raised in Garramilla/Darwin, Baker now lives in Mulubinba/Newcastle and remains connected to her Indigenous language and culture through social media chat groups and online databases. Personal computer allows Baker to transcend geographical distances by “inhabiting the land” through digital wayfaring, sharpening her mouth with every keyboard click.

Truc Truong’s tornado-style installation I Pray You Eat Cake (2023) explores the conflicted feeling of living away from an ancestral land that is foreign to you, to exist as a migrant in a country that is not your own. In 1982, five years before Truong was born in Tarntanya/Adelaide, her family left Vietnam to build a life in Australia, farewelling a Saigon that no longer exists. On a scarlet-red, half-moon stage, Truong presents a peppering of mass-produced toys, found objects, and fabrics that evoke memories of childhood trauma and healing. I spot, for example, a gnarly crucifix fashioned from dishevelled Barbie dolls, and feel a childhood-rage that jibes with my own Asian migrant experience. When I was seven, my father surprised me with a Barbie doll—the type that would be classified as “stereotypical Barbie” in Greta Gerwig’s blockbuster movie. I suppressed my confusion with this Euro-faced, golden-haired plaything by using charcoal ash to stain Barbie’s locks and blackening her blue eyes with felt pen, so she could somewhat resemble me. I made what Gerwig might call “Weird Barbie”—because of course, any alteration that strays from confectioned Western beauty is an act of bodily dissent, a vandalisation.

The dark undertone of Truong’s candied fiasco continues: stuffed toys are dismembered, swapped with other body parts; a jade-toned Jesus statue rests on canned food; comedic horses parade around motorised lazy Susans; a lantern of pig’s intestines dangle from the ceiling. These symbols represent the discrimination Truong faced while growing up as a Vietnamese migrant, including taunts about horse and pig cuisines, religious tensions (one side of her family are Christian, the other Buddhist), and conflicts between Western and Eastern beliefs. By unabashedly exposing and toppling these cross-cultural signifiers, Truong relieves herself from the “model migrant” pressures of her early life, facing her trauma head on.

Christopher Bassi’s tantalising suite of nine framed oil paintings of seashells gestures towards the history of fishing, pearling, and shell trade in the Arufa Sea. For Monuments to the South/West Waters of a Great Ocean (2023), the Meanjin/Brisbane-based artist places contorted pearlescent and dotted shells against a rusty-merigold background, turning them into fantastical monuments that resemble neoclassical scenes.

The Meriam and Yupungathi artist takes his title from the Arafura Sea (a semi-enclosed continental patch that sits between northern Australia and Indonesia) and his mother’s country on the west of the Torres Strait and Waiben/Thursday Island. Bassi began painting at seven, after his mother signed him up for art lessons. Today, his resplendent still lifes of the natural world exude the warm, tropical tones of Far North Queensland and the Torres Strait. They also subvert Western painting conventions by injecting subjects that recentre his own culture, history, identity, and place. Smith echoes this in Primavera’s exhibition audio guide, asking: “what would the European art history canon look like if perhaps the past was more equitable?”

Also glimpsing into the past, Hong-Kong born artist and curator Nikki Lam bases her video installation the unshakable destiny_2101 (2021) on a seminal 1997 speech made by Chris Pattern, the last British governor of Hong Kong. On the occasion of Hong Kong’s return to China after Britain’s 156-year colonial rule ceased, Pattern declared: “Now, Hong Kong people are to run Hong Kong. That is the promise. And that is the unshakeable destiny.” Twenty-six years on, the destiny has in fact proven very shakeable, with many Hongkongers expressing outrage at China’s sovereign control over an island that was promised economic and legal liberation from the mainland.

Lam’s site-responsive film lures me in through an oblong viewing port that separates the brightly-lit gallery from its dimmed screening room—like a wormhole tearing through spatial dimensions. I enter through a beaded-curtain cascade and into a theatrical set that pays stylistic and cultural homage to Wong Kar-wai’s visionary 2000 film In the Mood for Love, set in 1960s Hong Kong. Chinese stools cluster next to a wallpaper patterned with Hong Kong’s orchid flower of freedom, items that are mirrored in Lam’s six-minute video. Here, we see a slick-haired protagonist who seems caught between past, present, and future Hong Kong. As they orbit between rooms and subworlds, they fidget nervously, starting at the clock and shining lasers into the dark unknown, unsure of what’s in front of them, or what they’ve left behind. Clues arrive through English and Cantonese texts on screen:

The present is nowhere to be reimagined

We forget the past at every turn, but the body remembers, the image remembers

Memory / record

記憶 / 雷科

Screening alongside this work is The Unshakeable Destiny: Release (2023), an eight-minute dream-hazed digital animation that functions as a portal between the works in Lam’s filmic trilogy (the one on display here is the first). Normally based on Naarm/Melbourne, the artist spent this year living in Britain as part of her Acme London residency. By critiquing the oppressive systems that shape identity, history, and place, Lam reveals how political rage can be maintained from afar.

In the week that I submit this review, political angst splinters the globe. In Australia, a nationwide vote to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in the Constitution fails. Missile strikes are descending upon Gaza. The Sudan war continues. Despondently, I wonder: how can hope survive in the cracks of this widening sorrow? In Smith’s essay, she alludes to the communal exhaustion of having to navigate structures that effectively benefit a few, resulting in its failure to protect those who need it the most. She also speculates: “how are we creating our own systems and what do they look like?”

Seeking solace, I think about the artists in this exhibition, and the avenues in which they have created fugitive systems, codes, and narratives to re-imagine new possibilities. I think about the legacy of Primavera, which has housed over 250 artists to date. This exhibition series has been a hit-or-miss affair throughout the years, but there’s no denying its mainstay relevance as a platform for future voices of artistic change. For instance, Iranian-born Hoda Afshar, a 2018 alumnus, has gone on to present a powerful solo show A Curve is a Broken Line at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (2023), turning her camera into a crucial instrument to spotlight marginalised people. I think about an Instagram Story from my friend Natalie, who visited Primavera and felt buoyed after watching the unshakable destiny_2101. There’s a scene where the protagonist opens a drawer to reveal a hidden Chinese character: 光. I ask her what this translates to, and she says “it means light, but it also means truth.” Amidst the collective grief and despair of our times, small truths can become a refuge, casting new light on alternative power relations and cultural inheritances; they offer us new ways to re-envision a future where time does not tick, but instead, spirals.

No time to hit Snooze—let’s wake up.

Mariam Ella Arcilla is a Filipina-Singaporean arts and culture worker who oscillates between community engagement, writing, editing, and digital producing. Based on Gadigal land, she collaborates with artists and institutions to turn radiant ideas into programs, publications and resources. She is currently the Co-Chair of Runway Journal.