Annabelle Stonehouse: Ornamental; Jane Bartier: Footfall; Same River Twice

David Wlazlo

I’m going on a kind of psychogeographic drive, sucked in from the regions by the gravitational pull of Melbourne toward the rift in space called the Maribyrnong River. Passing through many local government areas and acknowledging countries along the way, I’m going to drop in to two of my favourite, smaller, medium, real, non-spectacular and awesome galleries: Platform Arts in Geelong and the Footscray Community Arts in Footscray.

Like a village with fast internet, these spaces operate within their communities and for their communities. Vibrantly multi-purpose, these spaces offer studios, outreach and workshops as well as diverse performance and exhibition programs. They’re the kind of arts spaces that quietly hum away outside and around the orbit of the larger galleries like the NGV and ACCA. While these other spaces often lay claim to a global and historical impressiveness, what I like about Platform and FCA is their ability to integrate into the particular culture of their own local space. They are orbital and more often than not eccentric. Of course, I mean that in a good way: culture that circulates around a body of mass (black hole?), seeping up through the cracks by capillary action, finding a way to nourish and hydrate in spite of whatever structure is already—or not—in place.

That’s the way I see psychogeography in any case: exploring the cracks left by mainstream culture. The term, coined by the Situationist International in the 1960s, involves the intentionally aimless wandering and meandering through urban space in order to experience it outside the restrictive instrumentalisation of capitalism. What does it mean, for example, to travel through the city and suburbs without partaking in this system of productivity? I say ‘psychogeographic drive’ but really it should be dérive, which was the term used by the Situationists. In French it means ‘drift’, which is something hard to do in my Toyota Yaris.

Platform Arts in Geelong, housed in an old courthouse building, has all the hallmarks of a structure repurposed but retained. The building exudes a sense of expired judicial productivity, which is all the better for us to drift through and around the cafe, the empty theatre, the offices and the backrooms that all still have their former purpose printed in gold lettering on the glass doors.

In the gallery space, Anabelle Stonehouse’s exhibition Ornamental shows ten of the artist’s ceramic vases. These works are around 45cm tall, hand-thrown and adorned using score-and-slip techniques They are decorative and glazed in pinkish-hues, adorned with pearls and tendrils. The vessels are presented in the centre of the room, on a range of different sized plinths. These supports are embellished with a flowing white cloth that takes away the harsh rectangular shapes of the plinths and replaces it with a kind of cloud or reef. There is a certain urchin- or coral-like quality to the works, enhanced by the pearls and pearlescent glow of the glaze.

According to the room sheet, Stonehouse is interested in ideas around femininity, feminism and ornamentation. The feminine is defined in this classical schema as something to be looked at, as ‘pretty’ and yet useful, performing a function (holding flowers, carrying something). There is indeed a certain orthodoxy at play here through the idea of the feminine as decorative, as vessel, as well as a certain folded viscerality of the nested mouths or lips of the vases, laced with pearls. Some of the works combine this sense of a body, both human and mollusc, with the more pinkish tropes of flowing tendrils. To me the most successful of these works are those that enhance the mollusc and the bodily, such as Fandangle or Pink Teardrops (2022).

These ideas of femininity, just like the idea of psychogeography, are something with a long history. They seem a little old-school. The idea of the feminine as conveyed by a decorative vase or as a vessel of any kind is a little old fashioned to me: do people today really think of femininity in this way? At least that’s what I was wondering last week. Now, after the insane US Supreme Court ruling overturning Roe v Wade last week, I’m not so sure. Are we back to regulating and legislating our sisters’ bodies once more? The idea of the feminine defined as a vessel of any kind makes me want to reach for my pitchfork (no, no, not an insurrection, you understand). Of course, I don’t think Stonehouse uses these well-worn tropes of femininity uncritically, but it is amazing how an artwork can reactivate according to historical circumstance. Art historian Dan Karlholm uses computing metaphors to desribe artworks, saying that “the default mode of artworks is sleep mode”. By this he means that an artwork can lie dormant, in ‘suspend mode’ like a laptop with the lid closed. Along comes a historical moment or event and all of a sudden the artwork is active, more vibrant and even critical. These vessels seem to me now as suddenly and critically activated, like vases that can, at a moment’s notice, double as decorative molotov cocktails.

Jane Bartier’s Footfall (2022) occupies the other half of the gallery space at Platform Arts. Behind a movable wall, the artist’s netted and woven works hang suspended from the ceiling. There are two longer pieces about four metres long hanging horizontally, touching the floor in places. There is also a loosely woven bag. The material seems a collection of loose ropes and strings of all kinds, including jute, electrical wire and baling twine. Each work is the width of a small loom, including the bag.

In Bartier’s statement, she makes reference to the practice of walking, collecting strings and other objects as she travels through Wadawurrung country. String is one of those things that manages to find itself discarded all over the place, especially—in rural areas at least—the distinctive blue of baling twine. Finding these pieces as she walks, she weaves them into her work.

The idea of a walking-based art practice seems to be a key part of Platform Arts’ program, especially through the Field Trip series of events. These are local excursions that engage with the landscape (while walking through it), with some even referencing a kind of coastal dérive. These field trips carry a distinct post-colonial, exploratory flavour and Bartier seems deeply respectful of place. I do have a brief pause to wonder though, particularly about the woven bag, because it initially looked to me like a contemporary take on an Aboriginal Dilly Bag. Maybe it is, but for me I wondered if the artist had a claim to personal Indigeneity? But honestly, is it polite to ask? Would it ever be polite? After thinking about Stonehouse’s work, I’m shying away from any attempt to pin important topics onto another person. Any attempt to fix the body of another person, to “grab people by the facts”, is not what I am here for. I am drifting through, here to look at art not make moral judgements.

One of Bartier’s artist statements for her PhD research describes the process of weaving into a pre-existing wire fence. The fence-like nature of the hanging pieces in Footfall really resonates with me, especially as someone who grew up wandering around the countryside. This sense of a broken barrier is enhanced by the way you have to navigate the work in the space, and of all the hanging artworks I have seen over the years, the reference seems the least arbitrary. An artist who weaves fences forces the question though: how do you wander, drift and explore the psychogeography in a rural area? In an urban environment, public space is fractured and cracked, but it has a greater surface area than in the country. In the country, everywhere is private property, over the fence, and the best you can do for a dérive is to walk in a straight line along a road verge for endless kilometres. Private property is the enemy of generalised drifting. In the country, the cracks between properties can be very far apart.

So back into the little Yaris.

Footscray Community Arts is located on the banks of the Maribyrnong River in Footscray. The centre has two buildings: one larger space that has a large open gallery, workshop rooms, studios and a theatre; and a smaller building that shares gallery spaces with a cafe. The exhibition Same River Twice is in the second space, spread across two small rooms. Same River Twice features ten writers who participated in the West Writers program run by FCA. The writers (Freya Alexander, Kelly Bartholomeusz, Gloria Demillo, Sam Elkin, Ryan Gustaffson, Gurmeet Kaur, Gabriella Munoz, Monique Nair, Hiếu Phung and Christy Tan) reflect on the classical Greek philosopher Heraclitus’ (although the attribution is still under question) famous quote about flux and permanence: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man”. Writing as memory and place and heritage are all drawn up by the artist-writers. All are active writers with impressive projects and practices, and I am a little intimidated about writing about their work. It feels like being shown a bookshelf with work by ten different authors and having to sum it all up in about 2000 words. Sorry, people. It isn’t going to happen like that, much to my chagrin.

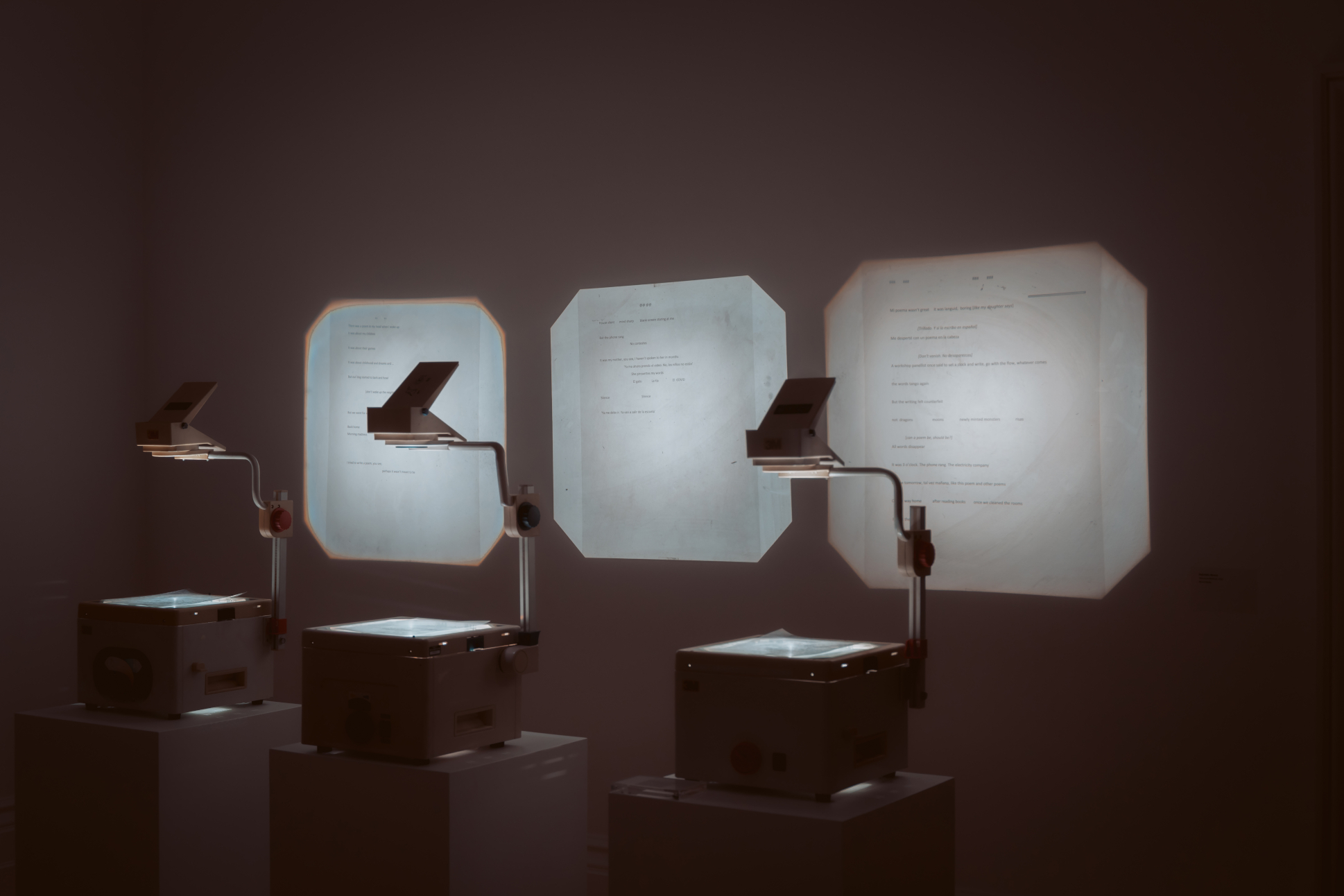

In the space, it is really interesting to see how the artists have engaged with the seemingly perennial problem that has plagued art since the 1960s: how to display text in a gallery context. Gabriella Munoz shows her poems on transparencies in Tomorrow/Mañana (2022), and visitors can interactively rearrange, layer and invert them on the provided over-head projectors. New poems and new meanings can be made out of these texts which are in both English and Spanish. Ryan Gustaffson’s Detour (2022) is a 6 minute audio track, accessible via QR-Code and accompanied by a dark filing cabinet full of documents. The text archive combined with the QR-Code produces a kind of meaning-in-excess of the work: where does the work end? How can you decide? The QR-Code in fact provides a portal to a something larger than the work. It produces, in shorthand, a Tardis-like rupture in time and space that exceeds any normal gallery visit. Maybe this is what I was thinking about when I described these places as villages with fast internet? Local, but with roots and meanings that are deeper than anyone’s single understanding. I’m back to being intimidated by the extent of the work.

Another audio work is appropriately (for me at least) called Drift (2022). The work, by Sam Elkin, is in the gallery space on a tablet on a stand with headphones. The text talks about water and walking and being around the river. You can see the river from the window as you listen. What is it about drifting, going on a dérive, that makes you run up against walls, follow cracks and fences and rivers? There are more cracks to trace here in Footscray because the fences are closer together.

Gloria Demillo’s work Elegy for Drowning, an interactive poem (2022) is a performance-poem that you part write and then share with a partner. Monique Nair, Hiếu Phung and Christy Tan collaborate on Bodies of Water (2022). Both of these works are presented on tables. Demillo’s work seems playful and fun, joking with the structure of the poem, but the text you have to play with is about mourning, trauma and rivers. Nair, Phung and Tan’s work Bodies of Water (2022) is also deeply involved in the ideas of inter-generational memory, love, healing and the loss of language.

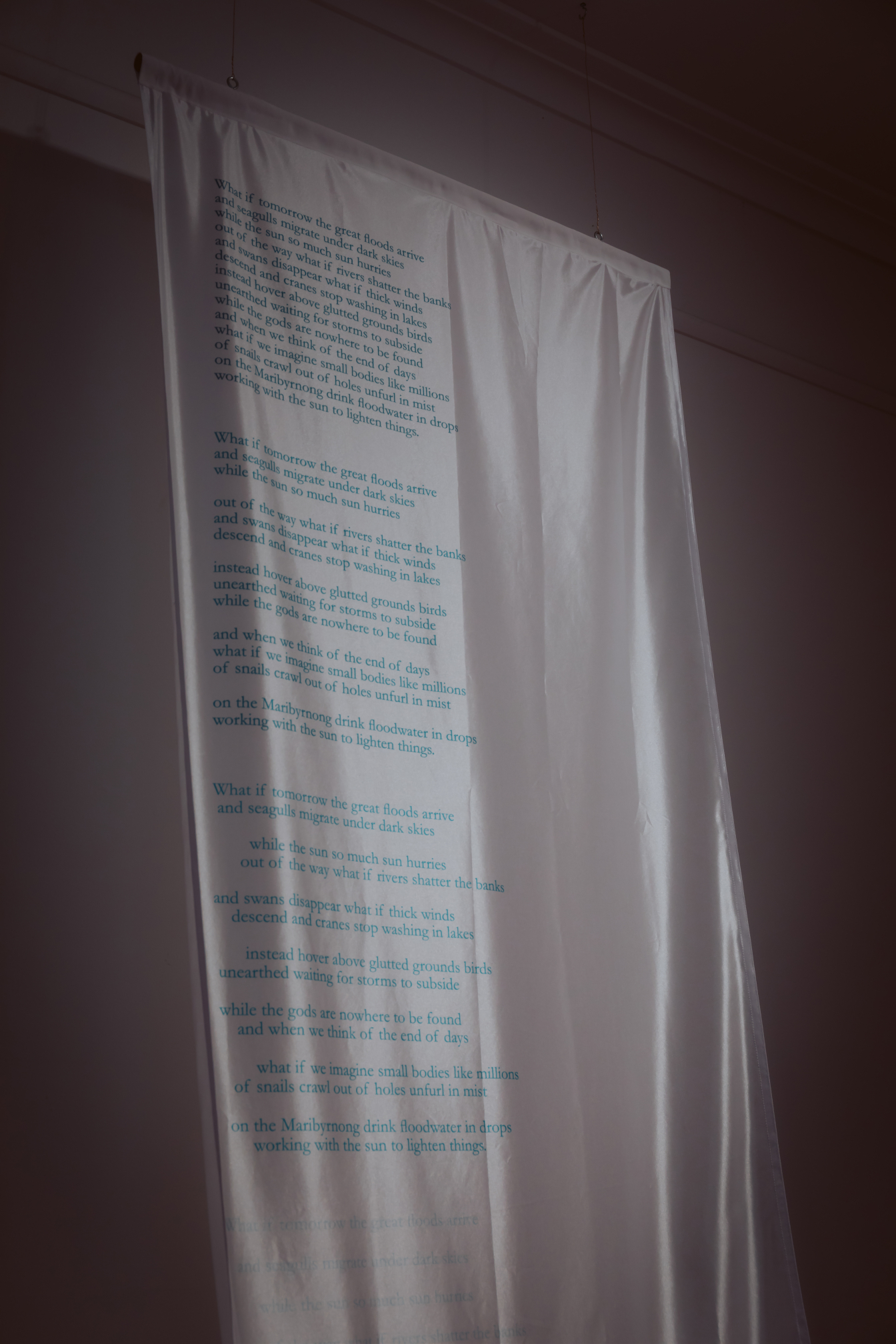

Freya Alexander’s three paintings Berringa, Wadawurrung Country I-III (2022) are abstract, alternating tonal and scratchy, their accompanying poem an impression of a particular landscape at Berringa, Victoria. Also on the wall, Gurmeet Kaur’s Flood Myth (2022) is a hanging cloth with a printed poem repeated down its length, with each repetition more faded than the earlier as the text slowly disappears as though diluted in the same waters. The poem’s opening line begins with the science fiction-like premise: “What if?”

For science-fiction resonances, I am really drawn to the work by Kelly Bartholomeusz called How to Build a Forest (2022). (It turns out that this work is also made by Jenn Tran. I told you this exhibition was like the Tardis). How to Build a Forest is a film projected on the wall in the smaller room, and it is based on Agnes Denes’ work A Forest for Australia (1998) in Altona. The film and voice-over is like a science-fiction future history documentary of a scientist returning to Earth to learn how to create a forest. The film reminds me of Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), black and white, based on still (or barely moving) images, temporal foldings, which of course makes me love it even more.

Driving into the city on this Situationist mission, I kept thinking about the cracks between private properties. How do these enable and disable thoughtful reflection on place, land and country? Underneath all the reflections on traditional ownership and acknowledgements of country there is this annoying fact: people own parcels of land, large and small. This perhaps really is the enemy of the dérive and also what makes this practice outsite the fence so critical. In stationary orbit, there are smaller galleries performing critical social, aesthetic and psychological work. Within these spaces I got to peak over the fence at some private and personal work, and as much as I brought my preconceptions with me they also managed to make a few productive cracks in me.

David Wlazlo is a writer, artist and IT worker who lives and works on Gulidjan and Gadubanud country in South West Victoria.