Pitcha Makin Fellas: Join the Club

Amelia Winata

In 2016, Ballarat-based Indigenous artist collective Pitcha Makin Fellas designed a jersey to be worn by Western Bulldogs’ players for Dreamtime at the ‘G— the AFL’s Indigenous round. Shortly after, it came to light that the AFL had used the jersey design in the video game, AFL Revolution, without Pitcha Makin Fellas’ knowledge, from which a bitter court case emerged. This blatant disrespect for Indigenous ownership was just another notch in the belt of the AFL’s longstanding ill-treatment of Indigenous people. Recent comments made by Collingwood Football Club’s now ex-President Eddie McGuire in response to Professor Larissa Behrendt’s Do Better report—which unearthed a long history of systematic racism in the club—were appalling but unsurprising in this respect. McGuire was, after all, the same person who suggested Adam Goodes should play King Kong only days after Goodes was verbally assaulted by a Collingwood fan on-field. Football has long operated as the litmus test for white invader attitudes towards Indigenous people, more often than not with enormously damaging ramifications. And yet football has historically also been a place where many Indigenous people have excelled and found communities. To be sure, most of the artists in Pitcha Makin Fellas follow AFL fastidiously. As such, Join the Club sketched the uneasy relationship that persists between Indigenous people and football.

Pitcha Makin Fellas (or The Fellas for short) was established in 2013 in the Ballarat and District Aboriginal Cooperative. The collective currently has four members, Adrian Rigney (a Wotjobalak/Ngarrindjeri man), Ted Laxton (a Gunditjmara man), Trudy Edgeley (a Gimuy Walubarra Yidinji woman) and Thomas Marks (a Gunai Kurnai man). For Join the Club, which was curated by Julie McLaren, the collective created an AFL hall of fame that represented the good, the maligned, the notorious and the categorically bad of the league—both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. It included work from the group’s four current members as well as two past members, Peter-Shane Rotumah (a Gunditjmara man) and Myles Walsh (a Yorta Yorta man). Join the Club was staged in a long, narrow gallery at the heart of the Art Gallery of Ballarat’s temporary exhibition spaces. Arranged in neat rows on the two long walls were thirty-eight equally sized synthetic polymer portraits of AFL stars from the series The Ugly Face of the AFL, all dated 2015-2020. At the far end of the gallery were three, large non-representational paintings that practically filled the entire wall.

Join the Club represented the complicated relationship that Indigenous people have with AFL. At once an exhibition of fan art and a criticism of the game, it drew inspiration from the archetypal fan commodity—the trading card—to tell this story. Each portrait was based upon the Scanlens AFL trading cards, which were produced in the 1970s and 1980s and distributed in packets of chewing gum. The cards depicted a player in a square or circular frame that was set against a single-colour backdrop. A quick Google Image search reveals a plethora of cards, depicting an entertaining array of footballers awkwardly posing, usually using a football as a prop. We see Leigh Matthews mid-air after kicking the ball, mutton chops thick and fringe full; Mick Malthouse (then known formally as “Michael Malthouse”) has been photographed up close, concentrating on the game ahead of him, his trademark cappuccino stain moustache is shown here in its infancy; Geelong centre-wing Michael Turner stares directly into the camera, his long blond hair cascading over his shoulders. Aside from the hairstyles, there is something garish about these cards; the images are very typical of seventies and eighties photography that is kind of grainy, overexposed and never fails to catch the sitter with a stunned expression. It might be said that the garishness has been translated to the Pitcha Makin Fellas’ portraits through their rough brushstrokes, distorted facial features and patchy shading—simultaneously endearing and grotesque.

Pitcha Makin Fellas work collaboratively on virtually every painting and, as a result, none of the works are attributed to a single artist. And, indeed, given that the group’s emphasis is upon collaboration, identifying individual makers is beside the point. There is also no hard and fast rule about what the collaboration between the artists entails. For one work, somebody might have painted the patterned background on the portrait while another painted the figure, with the rest of the group offering suggestions. Elsewhere, an artist might have completed a single portrait on their own. The uniformity of each painting and the grid-like layout of the works overlayed them with a sense of objectivity. But as with trading cards, there are always hierarchies, both subjective and objective. The grid formation represents bureaucracy, that is, the neat systematisation of work according to pre-determined rules and regulations. Therefore, to arrange the icons of Australian Rules football in this clinical fashion is to categorise AFL as bureaucratic: certainly in its current incarnation, AFL is a business just as much as it is a sport.

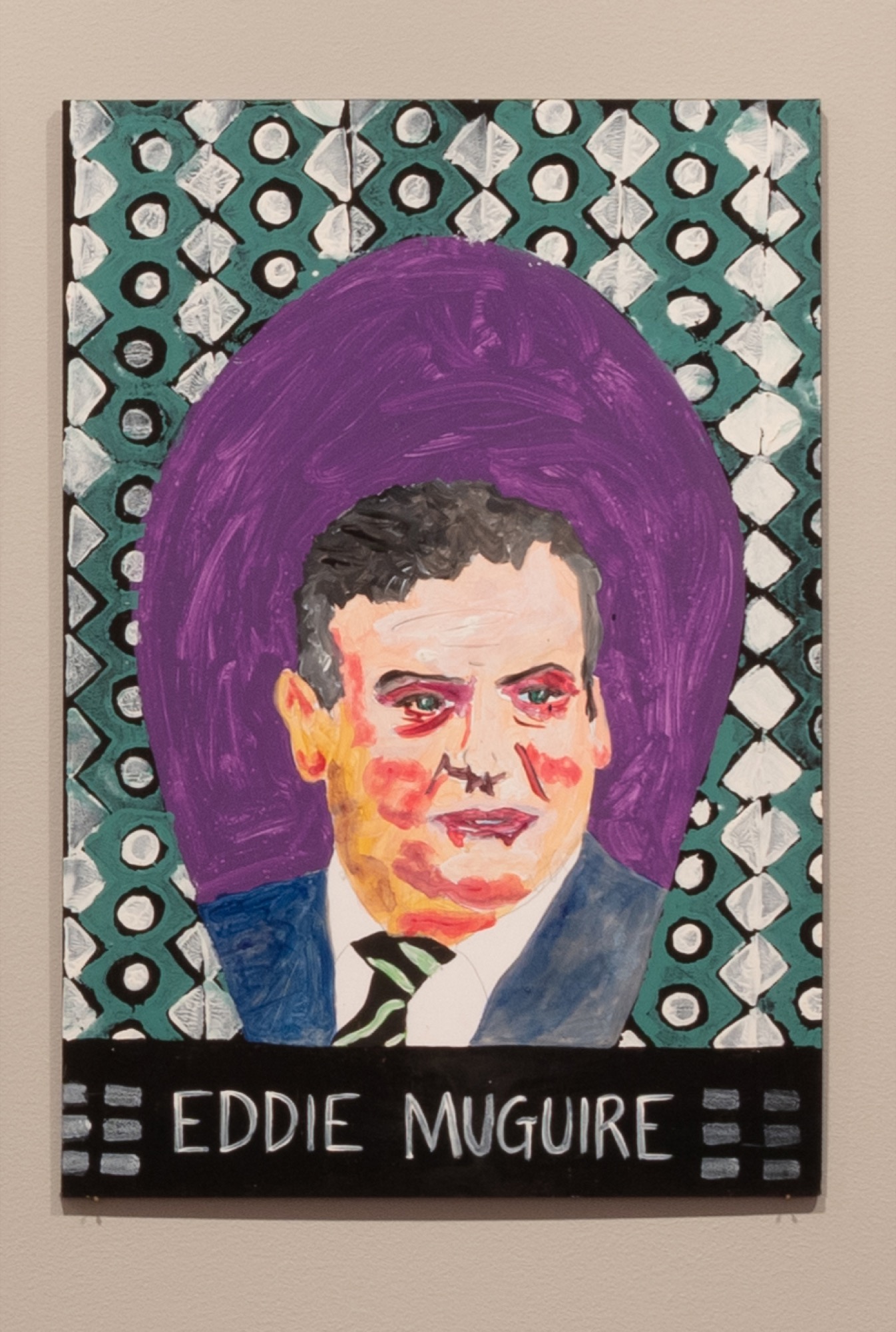

Relegated to their own cluster of paintings were, in the words of Peter Widmer who facilitates the Fellas, four “businessmen parasites”—the corporate entities who run the game: AFL CEO Gillon McLachlan (The Squatter); former AFL CEO Andrew Demetriou (Andy); former Carlton President John Elliott (Sucker Johnny); and, of course, Eddie McGuire (Eddie Muguire). The McGuire portrait looked as though it had been executed with a particular disdain for the disgraced Collingwood ex-President. Painted with broad, uneven brushstrokes, McGuire looked nothing short of gouty; maybe this was Eddie after a steak-and-Grange binge in the Collingwood lounge. At the same time the work might be understood as “painting as bashing”, which was indeed suggested by the misspelling of McGuire’s name to Muguire—”mug” meaning “to assault”, “to attack”, “to rob”. The purple shadowing on McGuire’s cheeks, chin, lips and eyes combined with the yellow mark extending from his neck to his ear also suggested bruising, as though Eddie had been involved in a bit of biff. The portrait was encircled by a dark purple “halo” that was bordered with a white pattern of diamonds and circles on a dirty teal green background—the painting reminded me of Neo Rauch’s neo-expressionism.

Next to the collection of “businessmen parasites” was a diptych of two works that were less representations than symbols of some of the other disagreeable entities that football attracts. The first was a bare piece of foam board with only the words “SAM NEWMAN” (Sam Newman) painted on the bottom. I am told that this is because nobody wanted to paint Newman, who is almost universally viewed as the bottom feeder of the football world. Next to this portrait was Twitter, a portrait of a man with two snaggle-teeth protruding from his mouth, red pimples spotted all over his face and a five o’clock shadow. In the words of Fellas member Adrian Rigney who painted the portrait, the person in the painting “looks like Cletus (“the slack-jawed yokel”) from The Simpsons”. Twitter was produced in response to a racist Tweet directed at Indigenous Carlton player Eddie Betts in June 2020 that compared him to a monkey. Rigney says that the portrait represents the “Twitter heroes who get their own (trading) cards”—alluding to the communities of football fans who use social media to express their racism and are, in turn, applauded by other similarly racist fans.

Not every portrait in Join the Club was as scathing as those of Maguire, Newman and the other “parasites”. In fact, the portraits of the other footballers complicated any black-and-white reading of the relationship that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island peoples have with AFL. The paintings evidenced love and admiration, despite clear structural racism, too. This schism was evident in Marcia Langton’s recent contemptuous assessment of the Collingwood Football Club fiasco, in which she also mentioned that she is a football fan with a Richmond membership. Even in the face of football’s disgraceful institutional behaviour, she remains a loyal supporter, calling on fans to safeguard the AFL’s “standing in the community” (although, to be fair, Richmond has a much better history of representing and showing respect for Indigenous players). Indeed, many of the portraits in Join the Club were acts of admiration, as opposed to derision. The artists’ characteristic use of unrefined and casual formal techniques were, in fact, a deliberate gesture of warmth. The accompanying exhibition text, written by facilitator Widmer, explains that “ugly” is “used in some places in the same sense that a words like ‘deadly’ and ‘wicked’: that matey way that nicknames are commonly used—sometimes ironic or endearing”. This was not to overlay McGuire and the other big bosses with a level of fondness but to show that ugly has many meanings. Where Eddie was represented as nasty-ugly, the players were largely represented as endearingly-ugly.

The titles given to each portrait assisted the viewer’s reading of the depicted football figures. The portraits were mostly titled according to professional nicknames, and were painted in bold lettering across the bottom of each work. Amongst them was Duck (Wayne Carey), Plugger (Tony Lockett), Tex (Taylor Walker) and Spida (Peter Everitt). These titles evoked familiarity and intimacy, overlaying the representations with humour and warmth. Pitcha Makin Fellas produced the works in the exhibition over a span of five years and, to begin with, the paintings were created to fill dead time between other projects. As such, there wasn’t really a particular criterion for which players they chose to depict. For the most part, they were players who had simply left an impression one way or another. Facekicker—Greater Western Sydney player Toby Greene—was remembered for kicking players in the face when on field.

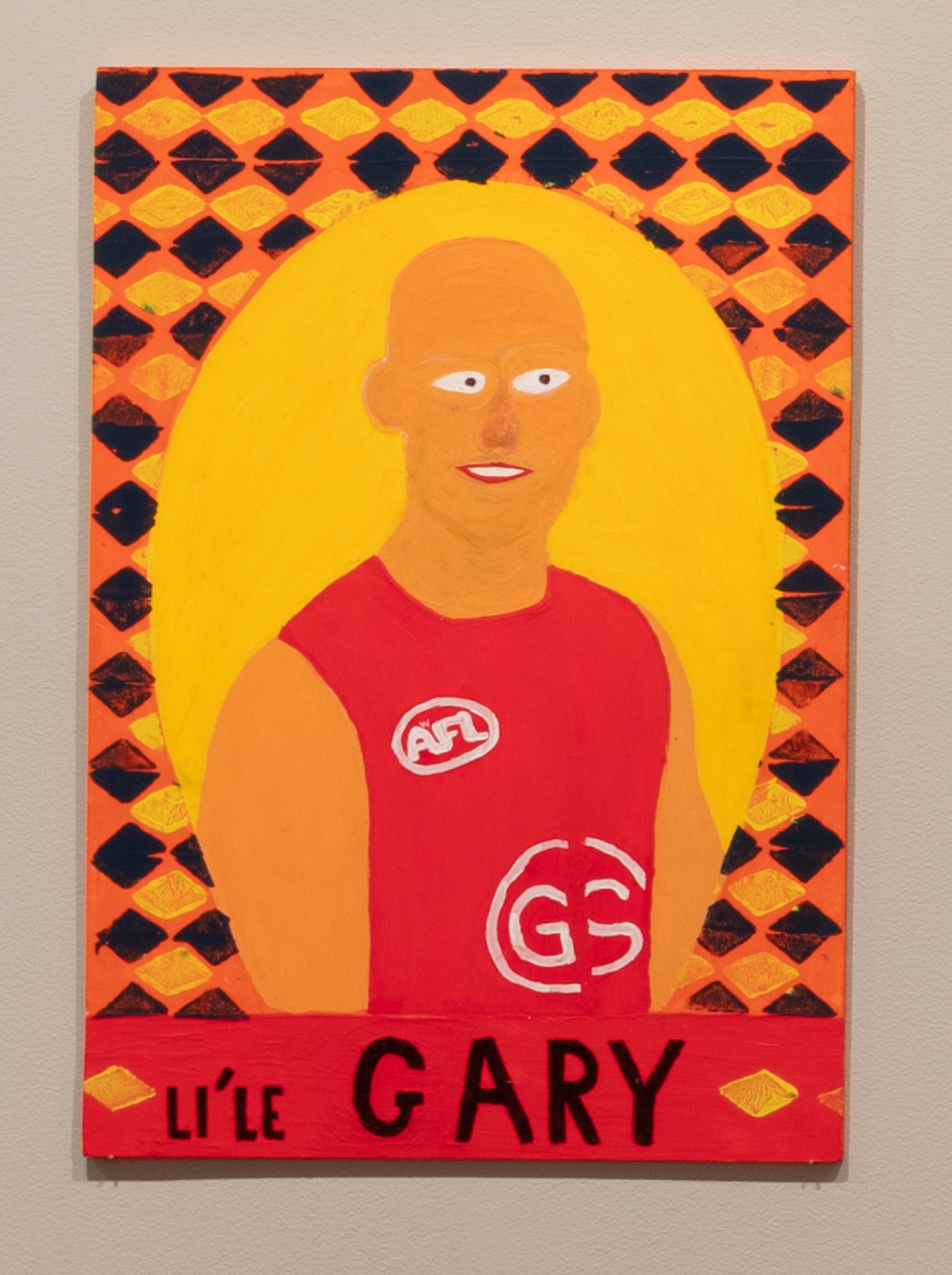

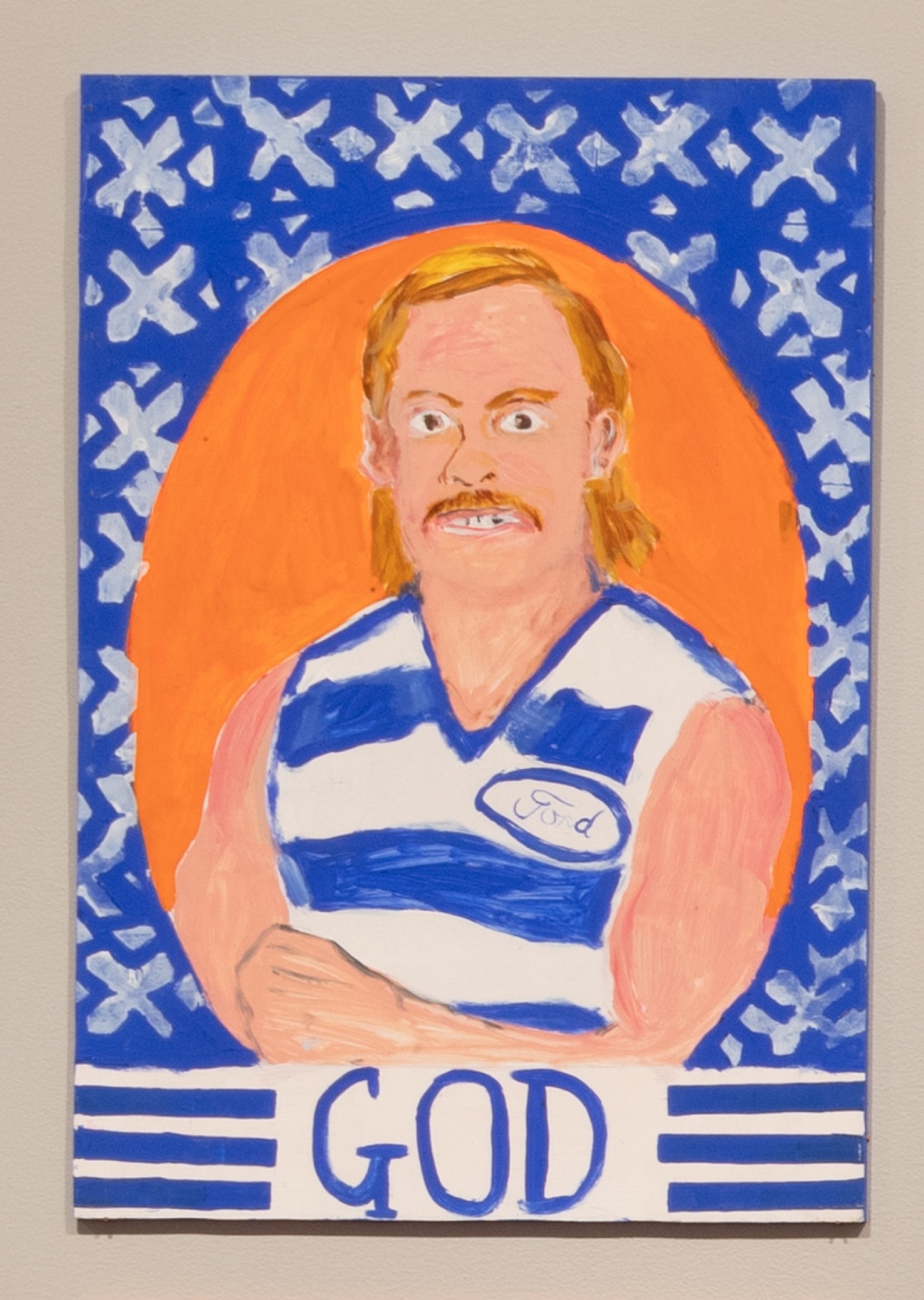

All of the footballer portraits were assembled in two large blocks facing onto one another. With their bright colours and broad brushstrokes, the paintings were captivating. Two works hung on top of one another, God and Li’le Gary, represented the father/son duo Gary Ablett Senior and Gary Ablett Junior. Ablett Senior famously went into a disastrous downward spiral that included drug abuse and violence post-retirement. But the title God placed the portrait in the arena of a religious icon, granting the disgraced star the admiration he garnered in his heyday. The accidental orange halo around Ablett’s head further suggested this connection to religious iconography. Even for people such as myself who baulk at the idea of AFL, the portraits elicited very personal responses—a sign of just how pervasive the game is in Victorian culture. I recall standing in line for hours after school circa 1995 at Owen Crowl—the Geelong equivalent of The Good Guys—to have Ablett sign my Cats jumper (meanwhile, Billy Brownless came to my primary school on “Footy Day”, signing one autograph and telling us to photocopy it). Li’le Gary somehow tugged at the heartstrings. Maybe this is because it depicted Ablett Junior decked out in his Gold Coast Suns uniform—the club that, for years, he so desperately wanted to leave to return to Geelong, which he eventually did in 2018. While overall quite featureless, the portrait was still recognisably Ablett Junior thanks to his Suns jersey and unmistakable bald head.

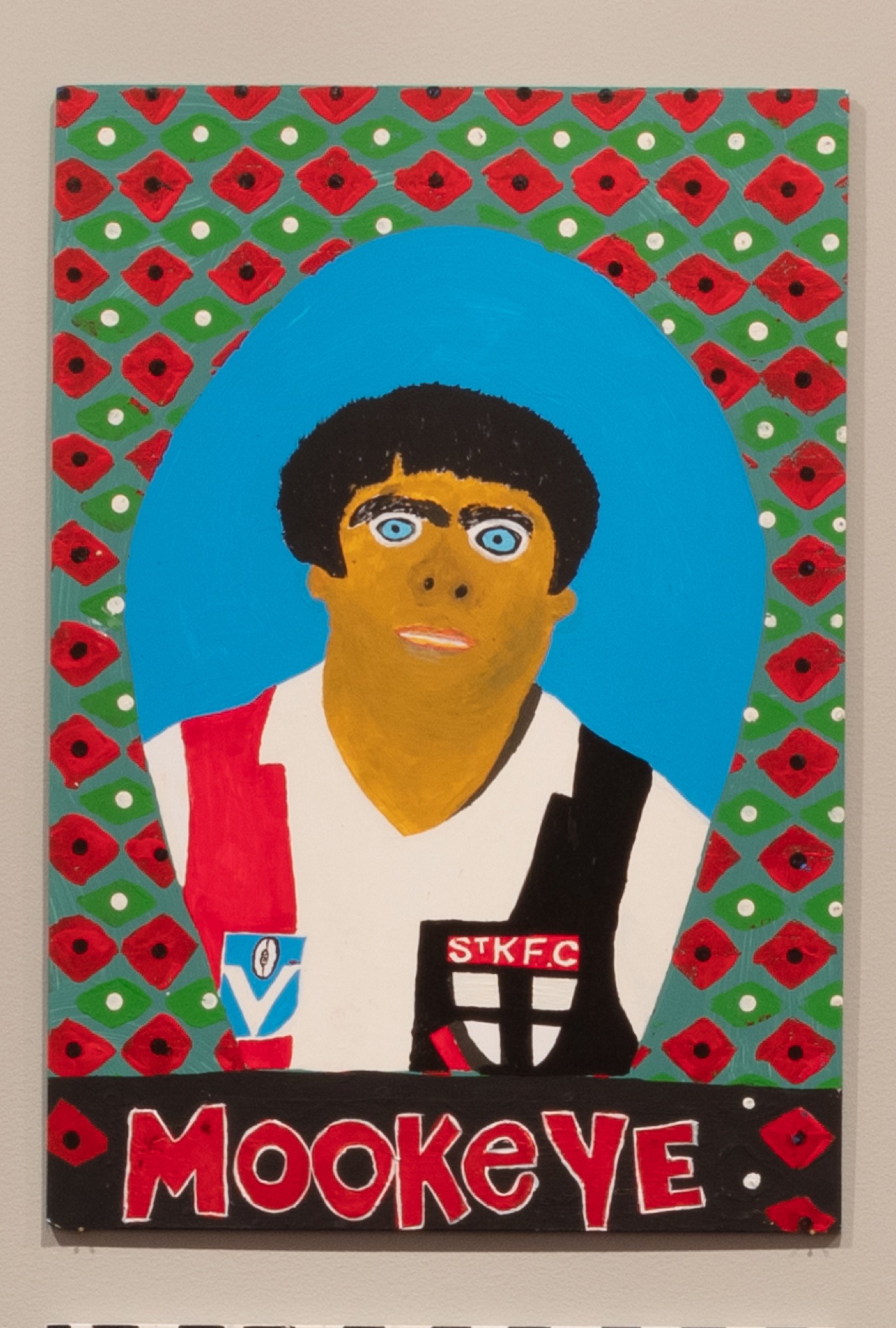

Unsurprisingly, some of the depicted players’ stories were centred on racism. Mookeye was a portrait of Robert Muir, a remarkably talented Aboriginal man who played for St Kilda in the 1970s and 1980s. During his career, Muir’s nickname was Mad Dog. This name was bestowed upon him as a compliment by teammate Kevin Neale, who used it to describe Muir’s physical endurance—Muir was said to sprint around the field like a “mad dog”, able to outrun all of his teammates. However, the nickname was soon twisted to racist ends, with it being used to suggest the myth of the violent, angry Aboriginal man. Throughout the 1970s, Muir was subjected to countless acts of physical and verbal abuse, which spanned from being heckled by spectators to being urinated on by a teammate. It wasn’t until the 2020 article by Russell Jackson, ‘The Persecution of Robert Muir’, that the extent of the abuse experienced by Muir became public knowledge. The article described in great detail the relentless systematic racism thrown at Muir and the lack of support that he received from the St Kilda football team. And yet in response to story, Muir’s former teammate Mick Malthouse stated that he believed Muir was “served well” by the name and that he seemed to like it—despite the fact that Muir has openly said how much it negatively affected him. Mookeye was comprised of flat colour fields—Muir’s black hair framed his piercing blue eyes that matched the painting’s blue halo backdrop. A pattern of red diamonds atop a green background surrounded this halo. The Robert Muir in Mookeye was anything but threatening and was, instead, represented with an almost child-like innocence. In addition, instead of using Mad Dog, the title Mookeye—a name that Fellas member Rigney says relates to the word “mook mook” meaning “ghost”—was chosen instead out of respect.

If the dozens of small portraits in Join the Club painted a picture of the AFL’s topology— ranging from those admirable players through to the worst of a bad bunch—then the three large works that were on display at the gallery’s far end represented the logic of Pitcha Makin Fellas as a collective representative of many language groups and cultures. Recall that AFL football most likely originated from the Aboriginal game Marngrook—named by the Gunditjmara People of south-western Victoria— and is a game played with a possum-skin ball. Nations and Clubs were three large panels intended to represent the interconnected nature of the various Indigenous Country groups of the Fellas. The two outer panels were adorned with various stamps made by Pitcha Makin Fellas, each of which represented a different language group. The stamps were then linked by multi-coloured, patterned lines to suggest their interconnection. The central panel conformed to a similar composition, except now the stamps were replaced with footballs each containing figures that represent AFL teams—an eagle, a tiger, a swan, a lightning bolt. Set against a forest green backdrop, the balls appeared to float freely around the picture surface but were also tethered to one another by various umbilical-cord-like lines also created by the Fellas’ stamps. Nations and Clubs’ emphasis upon connecting communities despite regional differences operated as an antidote to the regrettable corporate and racist facets of AFL—a reminder of the sport’s beginnings as an Aboriginal game.

Amelia Winata is a Narrm/Melbourne-based arts writer and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne.