Pierre Bonnard: Designed by India Mahdavi

Tara Heffernan

He examined the room as you do a doctor’s waiting-room … It was the purest distillation of the commonplace. He had become bewitched by its strangeness.

—Wyndham Lewis, Tarr, 1918.

The popularity of the confessional mode testifies, of course, to the new narcissism … The record of the inner life becomes an unintentional parody of inner life.

—Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism, 1979.

The work of Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) occupies an awkward place in art history. Today, his work is celebrated for its vibrant use of colour, his focus on intimate scenes of domestic life, and his manifest interest in craft and decorative art—interests he shared with Les Nabis, an influential group of young French artists of which he was a leading member. Though he painted until the weeks before his death at age seventy-nine in January 1947, at the time he was largely disregarded by his avant-garde peers. “He’s not really a modern,” Pablo Picasso said to his wife Françoise Gilot, “Bonnard is but a neo-impressionist, a decadent, a dusk, not a dawn.” Mere months after Bonnard’s passing, this critique echoed in the pages of the authoritative periodical Cahiers d’Art where Christian Zervos deemed the artist “weak willed, and insufficiently original.”

Detractors and supporters alike are guilty of over-investing in the surfaces of Bonnard’s paintings, in his intuitive and vibrant use of colour and pattern, and his scenes of nature and of bourgeois life. This preoccupation has resulted in the reductive interpretation of the artist’s entire oeuvre as a joyful meditation on bourgeois pleasures. The National Gallery of Victoria’s winter masterpieces exhibition Pierre Bonnard: Designed by India Mahdavi spectacularly perpetuates the joyful Bonnard by presenting his work in the “immersive scenography” of the Paris based architect and designer. Loosely emulating a domestic interior or stately home, Mahdavi’s contribution to the exhibition consists of wallpapers, furniture, and décor items, evidencing a desire to make palpable the chaotic interiors Bonnard recorded. Like a stage set, this immersive design offers an apposite reflection of contemporary culture’s obsession with exteriorising interiority—both literal and metaphorical—and the eroded distinctions between public and private space. Separated by the gulf of roughly a century, the exhibition not only provides Australians with a rare chance to see a large collection of the French minor master’s work, but the pairing with Mahdavi’s exhibition design also offers the opportunity to trace the development of a distinctly modern concern with interior life.

Organised in partnership with the Musée d’Orsay, the exhibition features over one hundred of Bonnard’s works, including paintings, drawings, advertisements, design items and photographs. Grouped by theme, the curatorial narrative adheres to a conventional, roughly chronological order. The first works encountered are categorised “Theatre of the Everyday,” and include Bonnard’s street scenes, many from his Some scenes of Parisian life portfolio (1895–98, published 1899). Then we move to “Decoration” and “The Nabi years,” featuring posters, prints, and advertisements designed by Bonnard, and works by fellow Nabi artists such as Édouard Vuillard and Félix Vallotton. These early artworks and objects are displayed in partitioned spaces. Perhaps inevitably, these introductory rooms create a bottleneck for visitors entering on a busy day, making it difficult to appreciate small scale works, especially when dodging posing Instagram influencers and TikTok dancers making the most of Mahdavi’s colourful backdrops. “Theatre of the Everyday,” indeed. From here, gallery goers funnel into an interstitial thoroughfare populated primarily by photographs of Bonnard with his sister’s family, posing or at play.

Though art, theatre, and the documentation of social life might seem like distinct categories, the thematic flow of the exhibition—and Mahdavi’s stage-like scenography—seem to coyly signal the collapse of their boundaries. The next significant section is themed “Music and Theatre.” Its most prominent feature is an excerpt from the 1965 filmed version of Ubu Roi, a scandalous play originally written by Bonnard’s friend Alfred Jarry, for which Bonnard designed sets and masks. This is not the only filmic feature of the exhibition. “Theatre of the Everyday” includes the Lumière brothers’ Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon (La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon) (1895) and Cordeliers’ Square in Lyon (La Place des Cordeliers à Lyon) (1895). Like Bonnard, the Lumière brothers captured everyday life on the streets of Paris with spontaneity. Their subjects occasionally notice they are being filmed, reacting with delight or shock at unwittingly becoming performers.

About a century ago, D.H. Lawrence described “the field of life” as “largely an artificially-lighted stage.” So too is the gallery space. The featured home décor items act as props. Hanging lights are largely superfluous against the ambient gallery lighting. Though occasionally attracting a sitter, the scattered furniture and rugs do little to distract from the gaping expanse of the institutional space and concrete floor with its industrial polka dotting of air vents.

Like many state galleries, the NGV has faced criticism for gender disparity in its major exhibitions, particularly the Winter Masterpieces series. The pairing with Mahdavi, a contemporary female creative, may be an attempt to deflect this, but it also reveals something telling about our current concept of greatness. Born in Tehran, Mahdavi’s childhood years were divided between the South of France, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Heidelberg, Germany. As countless profiles repeat, she watched up to three films a day as an adolescent and cites Disney as a formative influence. This juxtaposition evidences her status as an ideal consumer, informed by both high and low art. Consistent with the contemporary investment in credentialism, the wall texts provided by the NGV emphasise her cosmopolitan upbringing and proximity to important places and people. Mahdavi’s studio, we are informed, is only four hundred metres from the largest collection of Bonnard’s works housed at the Musée d’Orsay. Indeed, while the European male artist is today treated as suspect, Mahdavi embodies the ideal cosmopolitan subject: her currency is established by deferral to admired others (Bonnard) and her novel experience of important places, people, and institutions. She does not make art—which is itself suspect today—but designs spaces and furniture for communal use, imbued with the knowledge gained from a cultured life.

The interest in creating useful things for communal enjoyment echoes Bonnard and his Nabi colleagues’ championing of decoration and popular forms. In this regard, it’s an intuitive pairing. But the over-emphasis on the prettified aspects of Bonnard eclipses his fraught relationship with bourgeois leisure. Aside from a minority of notable exceptions, including Peter Schjeldahl and Helen Giambruni, surprisingly few writers explore the psychological disquiet apparent in Bonnard’s work. His domestic scenes often emphasise the rupture that can exist between people regardless of physical proximity. This is perhaps most jarring in Man and Woman (L’Homme et la femme) (1900). The painting depicts two nude figures, Bonnard and his long-term partner and muse Marthe de Méligny. The pair is separated by a privacy screen that vertically bisects the picture plane.

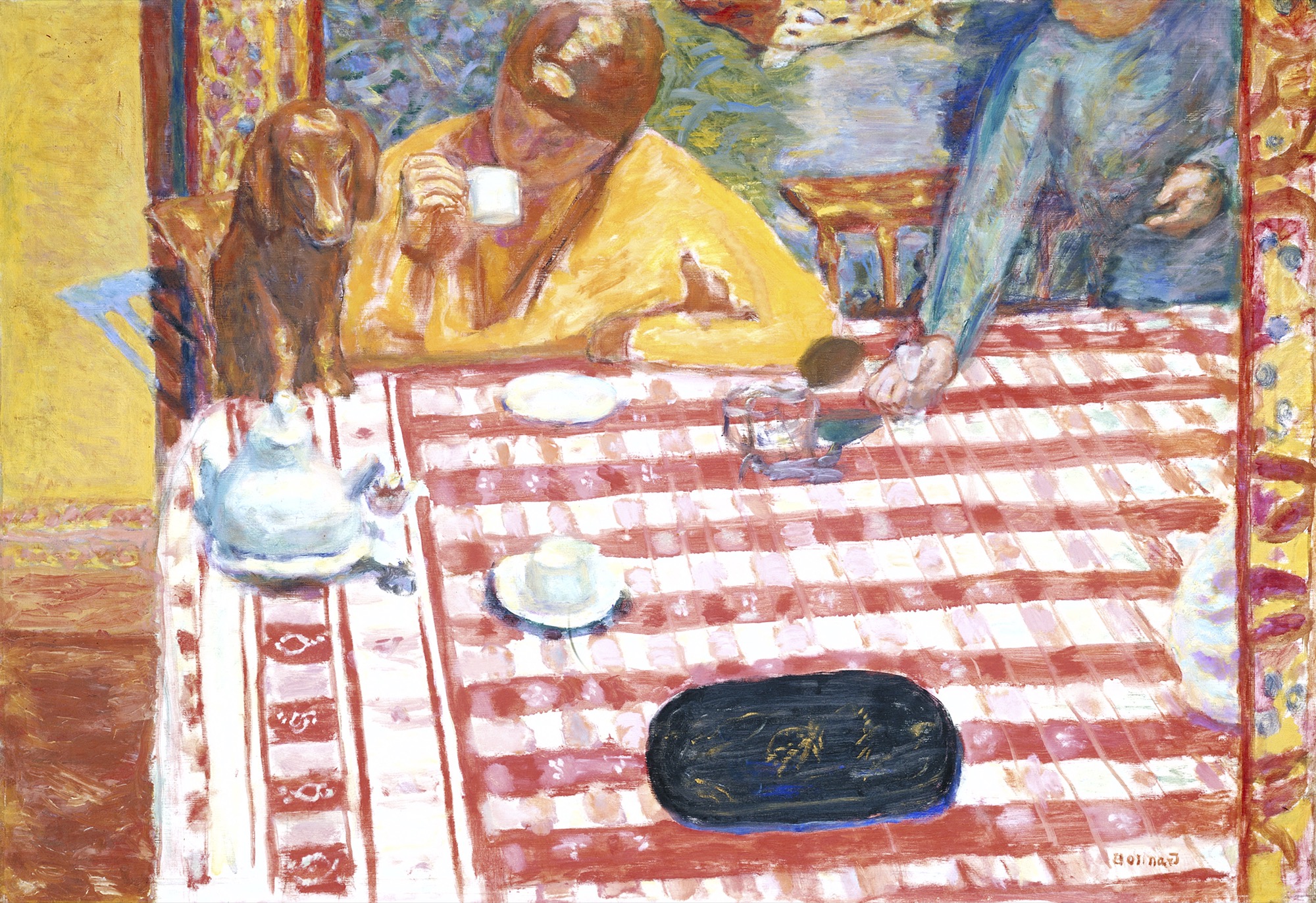

The voyeuristic nature of Bonnard’s work is clear enough in his iconic nudes. Mostly, these paintings feature Marthe. Her recurrent depiction in the bathtub, soaking supine or crouched with limbs akimbo, helped forge Bonnard’s mythology as the avant-garde wife guy. Rather than erotic, these depictions are equal parts banal and serene. Similarly understated, Bonnard’s interiors and bedroom nudes often capture the aftermath of a good time. We see the remnants of a meal and waning attention spans in The Red Blouse (Marthe Bonnard) (1925) or Evening by lamplight (c.1921). The latter displays content figures slouching into a table of empty plates, perhaps fatigued by conversation and digestion. A similar melancholy echoes in the post-coital disarray of paintings like Siesta (La Sieste) (1900). In this painting (part of the NGV’s collection) sleeping Marthe resembles a wilting still life. The ripe, traceable curve of her body ends with a left leg flopped over like a discarded banana peel. A little dog on the ground echoes the curve of her back with the hills and valleys of its form. An innovation of the Victorian era, the domesticated animal—bred small, passive, and stylish to suit apartment living—is another compelling feature of Bonnard’s interiors. Interior (Intérieur) (c.1920) features Marthe sitting at a table, gazing down at her hands, seemingly absorbed in her own thoughts. The dachshund to the side follows her gaze, apparently mirroring her in quiet solidarity. Indeed, to be with a pet is to be alone with company—a passive, agreeable companion for the inward focused subject.

Inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints of the Edo and Meiji periods, Bonnard’s compositions typically burst with detail, extending to the edges of the canvas rather than honouring its boundaries. Case in point is another rather quiet interior. Intimacy (1896) depicts Bonnard’s sister Andrée and her husband Claude merged with a wispy, ghost-like motif. Bonnard’s hand, clasping a pipe, encroaches at the bottom of the frame. Smoke hangs in the air, snaking from the men’s pipes and Andrée’s cigarette. Their breath becomes an ectoplasmic mist that merges with the wallpaper behind them—a bridge between bodies and the space they occupy. Mahdavi’s wallpapers extend Bonnard’s patterns into the space, though they lack the murky quality of the oil paintings and the mess of life they suggest.

The revisionist celebration of Bonnard’s work owes in no small part to his interest in the minor details of domestic life. Wendy Steiner praised this as a refusal of the universalist claims of (male) modern artists like Picasso, Bonnard’s great detractor. Conversely, the home was associated with “femininity and decorative craft … a sphere where beauty was tied to everyday interest.” One of Mahdavi’s more compelling interventions—a Warholian reproduction of the old matriarch featured in Édouard Vuillard Family Lunch (1899)—perhaps honours the role of women in the practice of craft and the domestic sphere. Here, Mahdavi might be lamenting a lost idea of domesticity and familial relations. Although we might note that interior design is itself a practice of outsourcing traditionally feminised labour—another way that the private realm has been co-opted.

Another interior, Under the lamp (Sous la lampe) (1899), displays a family united by lamplight while quietly engaged in their own preoccupations. A woman (Andrée again) tends to her child, while other figures bend over papers and books. Here, Bonnard captures something quite recent in modern social life: silent reading. Ushered in by rising literacy levels and increased leisure time, the act of asocial reading helped establish what we now call the “interior life.” Without the guidance of religious or community-sanctioned chaperones, the solo reader could forge their own interpretation. While a century ago, asocial reading was firmly establishing itself as practice for a new middle-class prone to introspection and intellectual curiosity, the practice—and the interior life it facilitated—seems to be crumbling today. A new emphasis on self-expression, encouraged partly by social media and therapeutic discourse, has revived reading aloud.

Bonnard’s relevance to contemporary culture is most pronounced in his fidelity to his positionality: on conveying his own perspective through his art, which he painted from memory or photographs rather than from life. This inward focus is completely compatible with contemporary culture’s obsession with self-referentiality. It’s no surprise that auto-fiction author Sheila Heti admires Bonnard. “Life happens so much in the mind and recollecting life and thinking about it,” Heti summarised, “Yes, that’s (Bonnard’s) wife, that’s his dog, but … the most important thing is how he sees his wife, how he sees his dog … His perception … is so much more interesting than what’s going on.” Expressing an inversion of the same truth, Bonnard reflected in 1945: “if we forget everything, only self is left, and that isn’t enough. It is still necessary to have a subject, however minimal.” Even some landscapes remind us of his insistent interiority, literalised in the ubiquity of windows through which they are often depicted, as in The open window, yellow wall (La Fenêtre ouverte, mur jaune) (c.1919) and Dining room overlooking the garden (The breakfast room), (Salle à manger le jardin) (1930–31), among many others. He remains inside, looking out.

What made Bonnard wimpy and insignificant in the eyes of Picasso is what makes him the ideal artist for our era. Today, for the writer, artist, public figure, and average social-media user, unrelenting self-expression—the externalisation of the inner-self—is not a deviation from convention and expectation, but the convention and expectation. The institutionalisation of self-expression, which manifests in feelings-based high-school curriculums and therapeutic workplace management, should make us wary of its current manifestations and prescribed avenues. A recurrent, and very Instagram-able, element of Mahdavi’s design inadvertently signals this truth. The interpenetrative potential of the window—a technology that engenders the modern breakdown between private and public, inside and outside—manifests as a motif. Glass-free rectangular windows throughout the gallery offer portals from public space to public space, revealing no genuine interior and protecting nothing. A letter penned by Mahdavi to Bonnard displayed in the exhibition summarises Mahdavi’s engagement with the artist’s work. “This encounter enables me to dive into your harmonies,” it concludes, “into your geometric and flower patterns, into your world—a pure sensation of colour—and to make it mine, just this once.” As a designer invested in colour and form, her desire to “dive into” Bonnard’s world and make it “her own” manifests primarily in simulacrum, the sampling of geometries, colours, and patterns. You can’t really dive into Bonnard’s world because—despite flaunting intimate scenes and poses—the unknowability of the figures he paints is his primary subject.

Vladimir Nabokov offers a germane critique of imagined connections in his final Russian novel, The Gift (1938). The protagonist, Fyodor, has many conversations with Koncheyev, a rival writer and begrudged influence, in his mind. Toward the book’s end, Fyodor expresses enthusiasm about their connection: “The fact that I know you so well without knowing you makes me unbelievably happy,” he exclaims, “for that means there are unions in the world which don’t depend at all on massive friendships, asinine affinities or “the spirit of the age.” But Koncheyev quells his enthusiasm, “At all events I want to warn you … not to flatter yourself as regards our similarity.” The name Koncheyev means a boundary, or an orgasm (another kind of endpoint). In part, the character reflects Fyodor’s grappling with art and “the narrow ridge between (his) truth and a caricature of it.” Bonnard might similarly grapple with that ridge, while Mahdavi relishes in the caricature. But this emphasis on aesthetics and untempered bourgeois platitudinal affectation is symptomatic of art’s role today, as something the viewer wishes to identify with or walk into (as we do Mahdavi’s exhibition design). The idea of entering an artwork was once a nightmarish prospect, so much so that being trapped in a painting was a minor literary trope. But today, we have come to expect art to be immersive, to open out onto our world, rather than show us something that might be, partially—and crucially—impenetrable. If we can take anything from looking at Bonnard’s art today, it might be a resonant respect for the unknowability of others that lurks behind sanctioned projections of sociability and openness.

Tara Heffernan is an Australian art historian and critic.