π.o., Heide

Victoria Perin

In Ian Burn’s near-perfect essay ‘Is art history any use to artists?’ (1985), he argues that artists have their “own sense of art history” that is derived primarily from an oral history of “stories shrewdly selected and edited to make the most telling points.” Heide, the recently published, epic poem by Melbourne poet π.o., is the greatest ode to local art history ever written and is itself a kind of radical art history in the terms that Burn imagined. So far, some reviewers have misunderstood Heide as a retelling of the history of John and Sunday Reed’s Heide circle, just with a bit of extra kick and gusto (as if π.o. parrots irreverently what academics have chronicled solemnly). It is, instead, an anarchist’s history written by a poet, an art history that shouts passionately about people and place in free-verse. Open Heide, and say hello to ‘John’ and ‘Sunday’ and ‘Barrett’ and ‘Sweeney’. Spittle lands on you.

{{ gallery }}

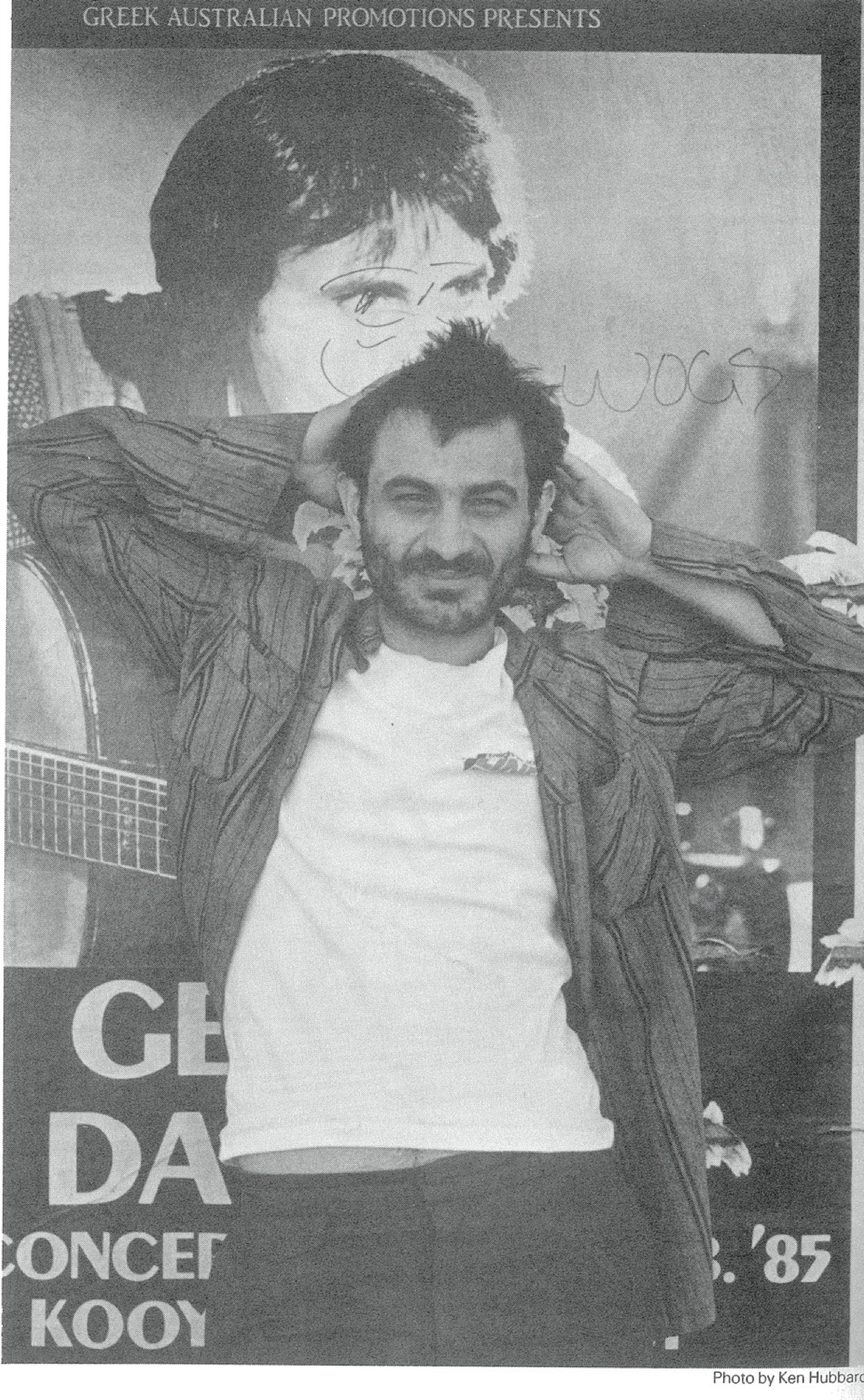

Unsurprisingly to anyone who has seen his captivating live performances, π.o. recently noted to the Los Angeles Review of Books that his epic poems “are in large part informed by their ‘performance’ — or to be more accurate, by their ‘orality’ and the ‘oral’ tradition.” Unlike an academic art historical text, Heide’s formal composition is better identified as a long anecdote. In ‘Is art history any use to artists?’, with its bold demand that academics be of use to their vulnerable subjects, Burn suggests that the anecdote is a version of history on a human scale. Writing as a Melbourne-trained artist himself, Burn insisted that you could know the art and artists of your local area (past and present) as colleagues, and that stories told amongst peers have power derived “from the fact that it personalises, conveys an intimacy and, as a rationale, is reinforced by the dominant art teaching practices of learning from examples and role-models.” In Heide π.o. has plumbed the depths of Melbourne’s art history and has returned with a compelling account of a creative anarchist tradition, of which he understands himself as an inheritor.

Despite his central position in Australian poetry, π.o.’s work is under-reviewed, as if his mammoth collections take up all the words that people might use to write about him. With a total of 549 complex pages, the poem needs more interpreters, not less, and won’t fit in any disciplinary cul-de-sac. (Due to π.o.’s persistent obsession with numbers, it certainly needs cross-disciplinary attention from mathematicians). The poem is separated into small “portraits” or “biographies” of individuals, locations, events or objects. In one of the most important sections, called ‘Eden’, π.o. cheers us on:

Between 1914 and 1935,

“Babe” Ruth hit 714 home runs: 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 = 1,

1 + 1 + 1 + 1 = 3, and 2 – 1 – 1 = 2, are 3

impossible events. Culture can’t just be imposed

from the top, no matter how much money you throw at it.

One has to get one’s hands dirty; there’s

a difference between the gas inside a balloon, and

the gas outside it. (449)

Are you in or out? Are you committed to working for the arts? π.o.’s own credentials as a relentless organiser for poets and artists, workers and protesters is beyond reproach. Due to the example that it sets as a revisionist oral history, it is an exemplar text for our time and place, and should be read by all who have a stake in the shit-show we understand as the “art world”.

All sophisticated art histories are located histories. It is impossible to appreciate the Renaissance distinct from the idea of Florence—‘Melbourne was no Florence, and Nolan / no Renaissance man’, π.o. cracks (336). For better or worse, the two locations in Australian art history that have had the most ink spilt over them are one in the same place: Heidelberg, a once-pastoral district. Heidelberg’s art history is double layered by the Heidelberg School, a group of impressionist painters who set up easels for two summers in 1888/89 and 1889/90, and then ‘Heide’, a home established in 1934 at Heidelberg by the Reeds, who were modernist art patrons. ‘Important things come in clusters’ (501), Heide is born from all the words written about art in relation to this place on the fringe of Melbourne.

Heide is almost halfway done by the time we get our first full piece about the Reeds (“Marry Me”, 248). In his accounting for a history of place, the poet finds it necessary to detail how this property could ever have been purchased and owned by the upper-class Reeds, making it clear that this is a tale about one property specifically, as well as the idea of “property” in general. The invasion and theft of Indigenous lands are rotten foundations, and π.o. specialises in slinging around the stink of colonisation. The initial half of Heide dwells with venal settlers squatting all over the region and climaxes in the manic ‘Old Pioneers’ Banquet’ in which the colony leaders play-act as disgusting gentlemen:

A frightened shark swims off, in a figure 8.

The largest piggery in the World, was Yugoslav.

Charge your glasses, Gentlemen!

This looks like

a good place

for a Village (56)

By this time, cattle and sheep running have stomped over enormous swathes of the country, and this onslaught is compounded by the pockmarking of the goldmines after the beginning of the gold rushes in 1851. “Ed said, he could smell it. He said the place / was “surrounded by gold”. There are 27 hundred different / species of mosquito.” (31). Although John and Sunday arrive later, their wealthy ancestors figure in this earlier colonial project.

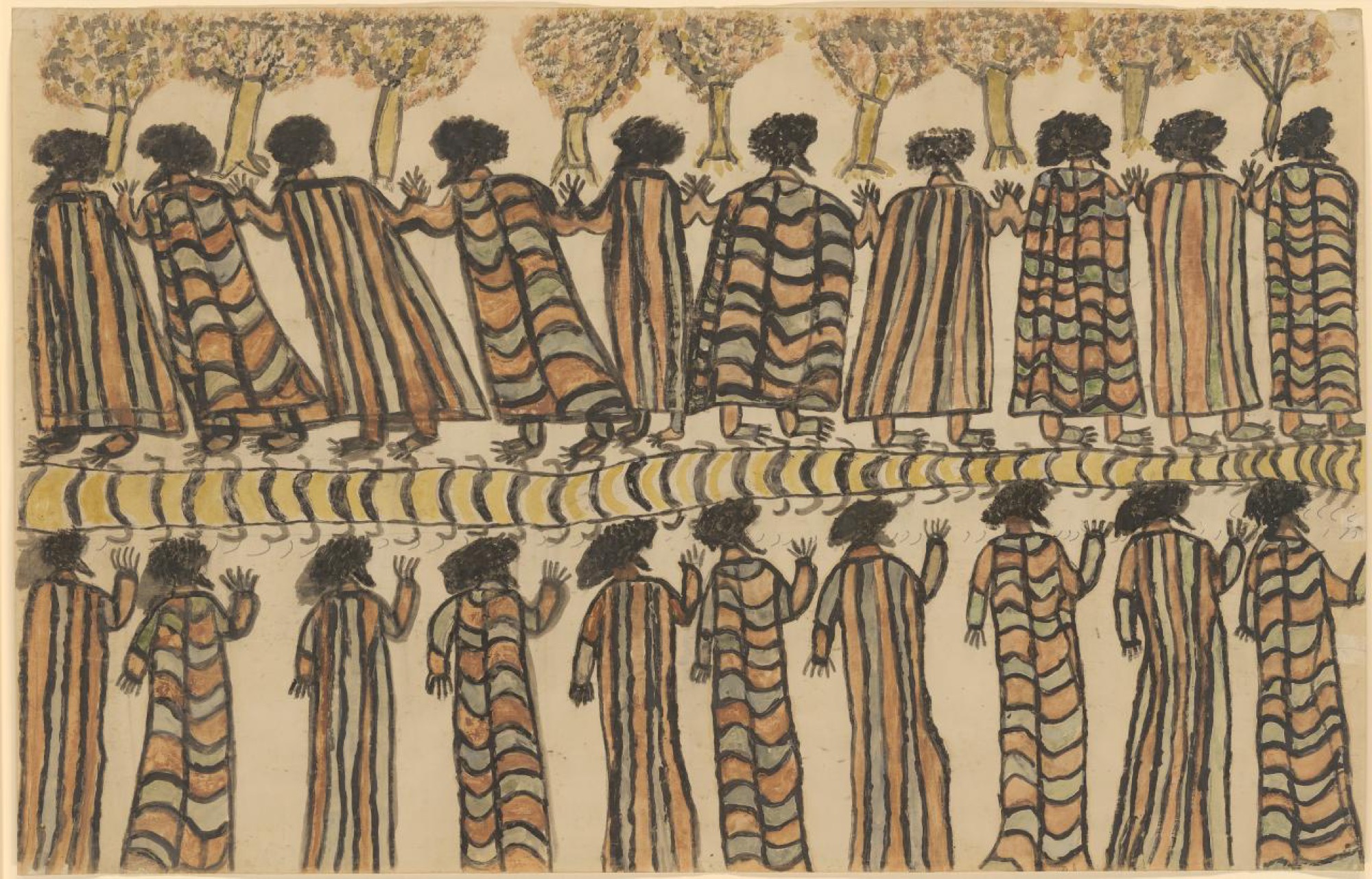

When it comes to the art history that π.o. has appropriated for this work, much is very familiar to anyone who has taken a university course on art in this country or been an attentive visitor to the Heide Museum of Modern Art, the institution founded on the Heide property in 1981. He begins his art history where many Australian art 101 classes begin today. William Barak, of the Wurundjeri-willam patriline that own the land that Heidelberg is on today, is the first single artist with his own portrait-poem (he also receives a second portrait later in the text); the next is Eugene von Guérard, the Austrian-born landscape painter first drawn to Victoria for gold-rushing. π.o., however, has read this now-standard history with focused, near obsessive, attention. Before getting to Heide, π.o. is enthralled with the machinations of the colonial art system; then after Federation he minutely delineates the various personalities chosen to purchase art on behalf of the National Gallery of Victoria’s wealthy Fenton Bequest. A litany of self-important, know-nothing toffs, the enthusiasm π.o. summons for this task is previously unconceivable. The poet takes on the role of the specialist, whose job it is not only to care about the charismatic heroes, but also history’s pissants.

I have no qualifications to lecture about π.o.’s poetry, but I have read some of the same art history he has read to write Heide. The form of each portrait section abuts derived art history plotlines with a cacophony of information: visual marks and ciphers, trivia (like Babe Ruth’s batting achievements; the many, many species of mosquito), equations, statistics, proverbs, declarative sentences and the significance of slang. All of this is combined with a comma that behaves both like an exclamation mark and a rock to stub your toe on (“Punctuation behaves / like a traffic signal.”, 133). Take the opening “facts” of ‘Images of Modern Evil’, titled after Albert Tucker’s virulent wartime painting series:

Hitler was born, in 1889 —

before Federation. Trains go faster and faster,

as the miles //// fade into the distance.

33333 is 5 blokes huddled together under a blanket.

Fidelity is a feature, of human virtue. What advantage is it

for a woman to know the dark side of existence,

and its shadows? (375)

While traversing voices and implications (the paternalistic final line is aped from Tucker’s own misogyny; and has anyone before fused Adolf Hitler’s birthday with Australia’s Federation in 1901?), each line is nevertheless delivered as a statement of truth. Befitting his self-styled union of poetry and maths, π.o. treats the word ‘is’ like an equals sign: ““Is” makes two things the same”, he writes (171). The effect of π.o.’s “encyclopaedism” is a cascade of relentless factoids that the poet wields like a hammer wrapped in silk: “π.o.’s quotations,” wrote Ivor Indyk in 2016, “like (Walter) Benjamin’s, make an appeal to the reader’s convictions, as well as to their emotions. Relocated in the poems, they take on an extraordinary power.” Indyk, went on to publish Heide under his Giramondo imprint (previously π.o.’s books have only ever been self-published via his own Collective Effort Press). Indyk unequivocally describes the emotional impact of this collaged style as π.o.’s “mastery”.

π.o.’s selection of art history fragments shows an interest in established narratives: “There is no good Art, / without a past” (372). “Often”, he emphasises in a key line at the start of the book, “i leave an Art Gallery, or a painting, feeling / uncertain, about what i / just saw” (19). We can all recognise this feeling. Words, perhaps, mediate this uncertainty. And wherever π.o. has found many words on a topic, he has dissected the accounts to extract the voices of those long dead in order to plot a vast network, an interconnected world. If you were so inclined, you could illustrate this text with nodal diagrams. These lines would chart familial and political ties (both left and right), friendships and rivalries, bureaucrats and their bosses, illicit or ill-advised sexual partners, and most broadly and persistently, the binds and flow of money as it relates to art.

π.o.’s central claim, the rod that holds the poem together, is that the Reeds were anarchists in the tradition of English art historian and literary critic Herbert Read, and that their art patronage was really the model for a collectivist lifestyle. π.o.’s account of the Reeds’ patronage is constructed out of the copious biographies on their artists (some of Australia’s, let alone Melbourne’s, most famous), and the publication output of the Heide Museum of Modern Art, notably the 2015 biography of the Reeds, Modern Love, by the museum’s curators Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan. While π.o. takes directly from such biographies, his conclusions are somehow far more aggrandising than an academic would ever dare to claim. Case in point: “Heide being, the proper study of Mankind / (Let me for instance)” (503). If we let him, π.o. will tell us that Heide, as a template, is Melbourne art history’s most detailed union of money, politics and love in action.

Bread and roses were once the twinned demands of female American textile workers. As a poet who started writing about ‘work’ in the 1970s, π.o. uses Heide to expand upon his constant interest in how those who already have roses, get bread. If Vasari’s artists had Lives, π.o.’s have Jobs. The patronage that the Reeds offered is shown in relief with the alternative of making a living as a worker first, artist second. π.o.’s description of the working-class lifestyle of Fitzroy-lad, Tom Roberts helps you to grasp his sympathies:

One must take into account

the inner world of the Artist; helping his mum;

working in a photographic studio by day, and sewing

leather // straps onto satchels in the evening.

An impression, goes without saying. The shortest

hymn, is the single verse “Be present at our table, Lord”.

Cigarette packets glued to canvases, are not Art;

best go to Art school, to find out what is.

Uneasy, is a hard place to come from. (Art is

an irresponsible career path). Unpaid, owing, owed,

due, payable. (144)

Although not every artist profiled is working-class—π.o. has lots of time for the independently wealthy “flower painter” Ellis Rowan, and devotes a beautiful concrete bouquet to her (141)—by the time John and Sunday Reed show up, we have met a cast of artist-paupers, people whose art is changed by the business of making a crust—Roberts, π.o. tell us, was excellent at courting clients and “began to paint in his Studio more and more, than / out in the //// scrub.” (135)

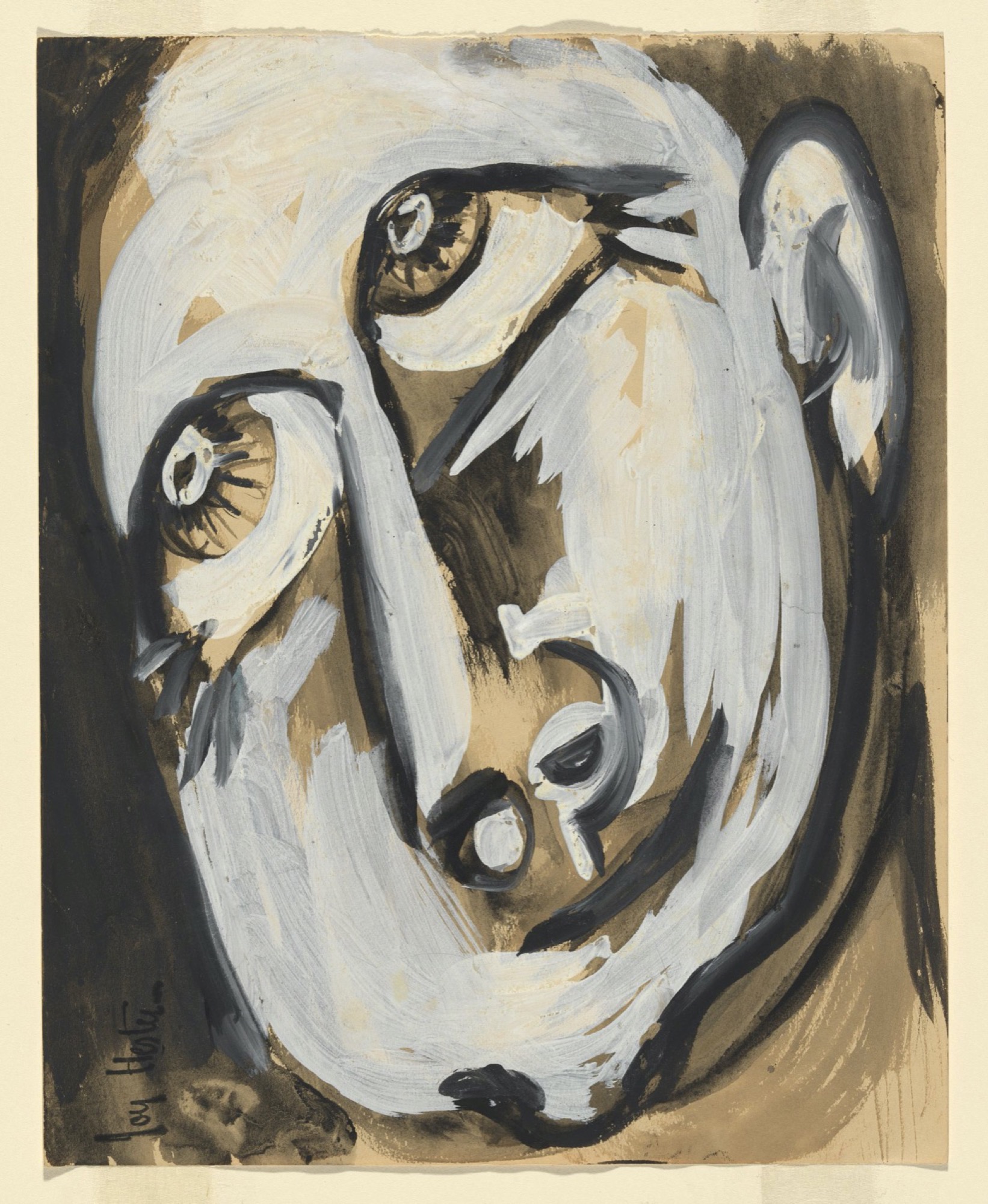

The Reeds’ money and attention (both often euphemised by the term ‘support’) changed their artists’ art by changing their lives. Joy Hester met the Reeds after starting to date Albert Tucker, who had quit his job after the Reeds bought two of his paintings.

Joy got a job as a “Hello Girl” for a taxi

company — on the phones. A hearing, is a trial.

Promising, means “likely to turn-out well”. Joy and

Sunday hit it off! Joy loved going over to the main house

to talk, and draw, and walk around. The purpose of

a mother’s milk, is to make a baby fat. (361-2)

Hester and Tucker hid out from the military recruiters in a shed across the road from Heide. π.o. tells us that ‘Joy & Sunday loved each other’, and that even though they fought viciously on occasion, Hester could truly work at Heide:

After a night of drawing & painting & sketching & scribbling,

she’d leave the results strewn across the floor; full of

stories about the “Leonski murders” that were

then in the News; Joy could see, the death of a “Hello

Girl” at a taxi service, in those newspaper reports. (362)

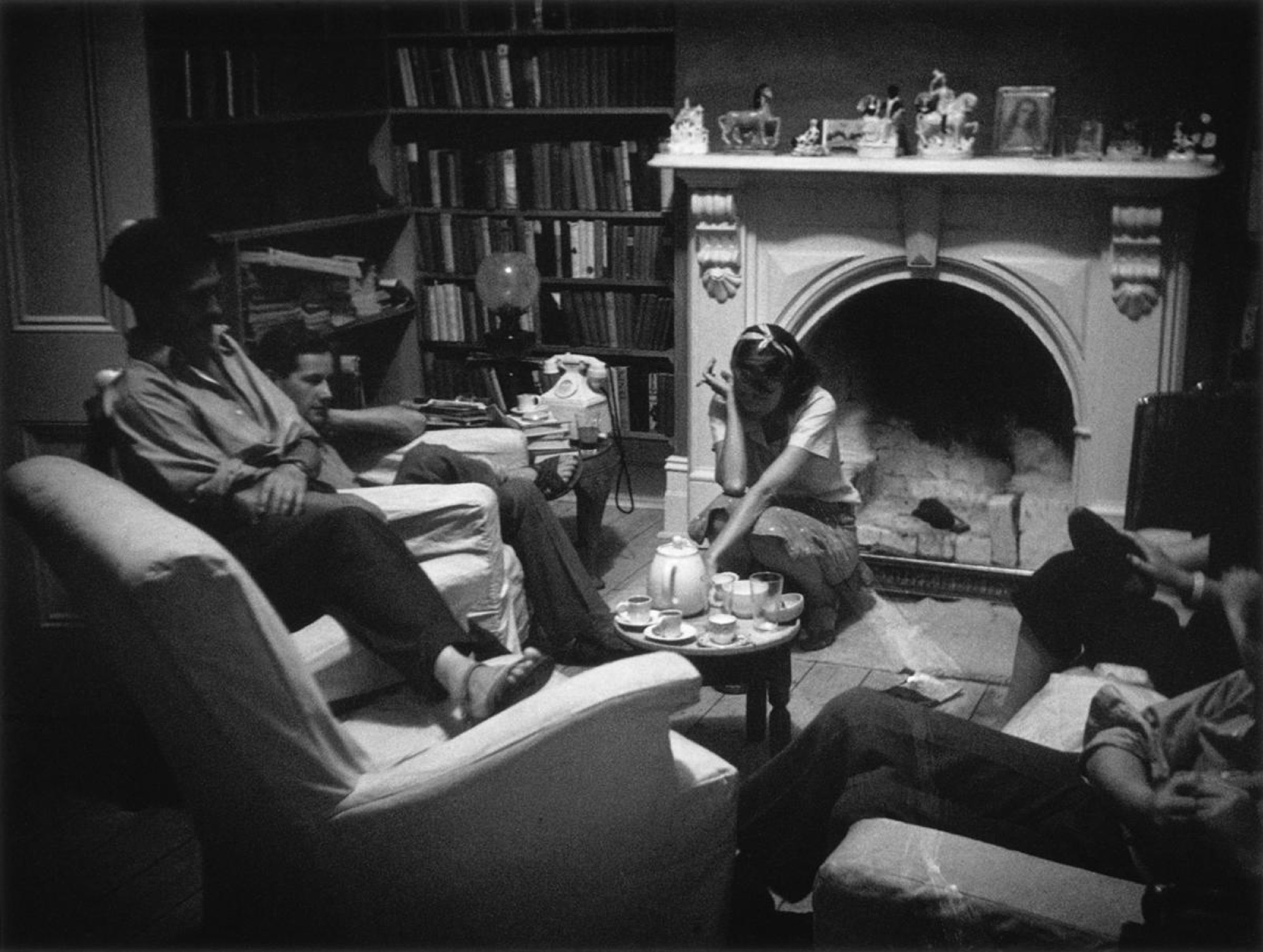

Here π.o. explicitly links the threat of a working-class existence and the salvation that a bit of affluence, when shared, can provide. The Heide library, somewhere to work; was less a room of one’s own than a room for them all.

π.o.’s appreciation of the Reeds begins with them being class traitors, members of the upper-class who were uninterested in “companies, stocks, shareholders, minutes, or riding around / the city in limousines.” (343) The poet celebrates their continued efforts to develop a reciprocal community in which they ponied up all the cash for everyone, and expected only reciprocity in chores and gifts: “Hey Genius, wash the radishes!!!!!” (484).

They were

all living, in the future — even tho nobody knew

what it looked like; jus’ so long as they were all together;

the more support, the better. All the muscles that

start in the neck, serve the movement of the head & shoulders. (269)

π.o. isn’t naïve or “sentimental” (as one reviewer has claimed) about this “gift culture”. He clearly marks episodes of ego, manipulative behaviour, aggression, tragedy and cruelty. Yet the ideal that the Reeds encouraged, an ideal that π.o. also believes in, “can be traced to Kropotkin, and his book Mutual Aid / in contradistinction to the Tarzanists theories of evolution / and the survival of the fittest).” (450) π.o. came to anarchist politics in the early 1970s, and as an anarchist artistic organiser he is the successor to a lineage of Australia’s radical leftist poets, such as Harry Hooton and his close friend Jas H. Duke.

Why are we incredulous when, unable to let go of paintings that represented their intense relationship with Sidney Nolan, John wrote: “Your paintings were your contribution.” (480)? In many quantifiable ways (marketing, editorialising, exhibition staging, strategic donation, public and private advocacy), the fact that Nolan’s paintings ended up being extremely valuable was not the fault, but the result, of the Reeds’ support. π.o. too, I’m sure, believes the Kellys were both Nolan’s and Sunday’s.

An object is not

a commodity, but a relationship — giving a gift, places

one in one’s debt; time //// passes, and a counter-

gift is presented, and accepted, and no clock is involved, or

weight & measure; a “+ 1”, “- 1” transaction

= 0 (nought) / nought but goodwill — reciprocity.

Reciprocity is the basis of all non-market economies. (450)

Heide was not the only home of reciprocity in the local art scene. π.o. devotes time to both the Boyd’s Murrumbeena property, a “kind of commune” (495), and Georges and Mirka Mora’s café communities. But these generous places were all part of the same system of postwar political and social thought characterised by the unrestrained sharing of wealth and art.

The anecdote, Burn insisted, is instructive. In Heide π.o. tells us that “An Anarchist doesn’t have a blue print / to look forward to, to tell you how to live. Sorry, for / the inconvenience.” (527) Yet his poem contains endless historical examples of artists supported by their peers and sensitive patrons: “The first painting Matisse ever bought, was by Cézanne.” (270). Although as he recognises that “Gossip puts 2 and 2 together, and / gets 18” (525), π.o. cultivates an incredible credulousness around anecdotes like this that make up the art history in Heide. As Burn wrote “Neither the authenticity of the anecdote nor empirical veracity is an issue,” as an “anecdote creates its own necessity, truth notwithstanding.”

To this idea of necessity, π.o. has selectively published “new” anecdotes to add to the mythos of Heide. The poet knew the Reeds’ best friend, editor of the Overland poetry journal, Barrett Reid. Reid lived with his partner Philip Jones further out than Heide at St Andrews, and in a replication of the Heide model, the young, streetwise π.o. would “go there / most anytime, with a girlfriend, to get out into the country, / cos it was the only place i knew, where to go to / outside of Fitzroy.” (486) There is a subtle change in emphasis in these sections, where π.o. is now the primary source for these Burnian histories: “I can’t quite remember how i / know everything i know about Barrett, but a lot of what / people have said about him, is probably true” (487). The Reeds asked Reid to bring π.o. to Heide twice, but π.o. declined.

Yarning about the few times he hung out with the Reeds’ fragile son, the poet Sweeney, key themes of Heide—class clashing, distinctions between knowledge systems, the telling detail, the sharing of wealth—effortlessly coalesce:

I think, he liked the fact that

i grew up in a hamburger-sly-grog gambling joint (in

Fitzroy), and that i didn’t really like Artists, or

know anything about them, or him. He had a sports car;

that had a lot of Vrrooom in it

but he was generous. (490)

While he never went to art school, π.o. was unquestionably already a visual artist when he was hanging out with Sweeney in the mid-1970s, but his contribution to visual art via concrete poetry has barely been acknowledged in the art world. Whereas relationships frequently transgress the boundaries between one “scene” and another, academic histories find such messiness too imprecise, too easy to omit.

π.o.’s passion for vast local narrative is derived from his utter conviction that the world is in Melbourne and Melbourne (or Fitzroy, or Heide) is the world. To the Los Angeles Review of Books π.o. cited a line he uses often: “Archimedes famously said, ‘Give me where I may stand and I will move the earth.’” By the end of Heide, π.o. offers the same fact over and over again: “In 1757 there were only 3 cafés in Paris”, “In 1757 there were only 3 cafés in Paris”, “In 1757 there were only 3 cafés in Paris”. During the modernist period in Paris, a culture that spread all over the world was incubated in cafés in which you could sit all day nursing one cold coffee. The Heide Museum of Modern Art has a café, but as π.o. warns you “have to have a booking” (506). Melbourne today has many cafés, but not one can you currently sit in with friends. Even if COVID-19 had not closed them, are Melbourne’s cafés the type of gathering places π.o. is recalling? Do artists today have any place to meet? Where is art? How can an artist live? π.o.’s history has a vision: if some rich class-traitor would be so kind as to put up the cash, artists may be able to organise a way of paying us all back, tenfold.

Victoria Perin is a PhD student at the University of Melbourne.