Paradise Lost: Thomas Griffiths Wainewright / Herself

Léuli Eshrāghi

What I notice first and foremost on arriving at the entrance to the exhibition is the large title wall. A “fashionable dandy in 1820s London”, Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, is the the focus of a monographic show at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) on the nipaluna (Hobart) waterfront. His name appears in black text on an off-yellow background; the exhibition title proper, Paradise Lost, in large off-yellow text on a black background, with supporting funders below. I’m unsure what job a dandy does, but the allure of romanticising the long-dead whose work lies in a state art museum’s collection must be too great. I enter the “wrong” direction first, on the right of the entry text, and see the rusted, aged remnants of a door displayed on the “final” wall of the exhibition.

“Also an artist, collector, critic and essayist”, Wainewright exhibited at those deeply conservative centres of imperial aesthetic value and candour, the Royal Academy and the collectors’ society, the British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom. Relying, from the very opening wall texts, on framing the value of this “adopted son” of Tasmania through his engagement with these white institutions in the imperial home turf has got to be one of the most widely used strategies of white Australian art historians and curators. This is evidence of seeking validation and visibility precisely where Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) artists have (finally) taken more of centre stage.

I didn’t really comprehend the depth of attachment to carceral aesthetics in lutruwita until recently. This exhibition has an overwhelmingly dark and brooding feel, with spotlights focusing on the paintings, etchings, furniture and accessories. Around me, numerous elderly patrons struggle to view the detail of artworks, as most of the works are cordoned off along the length of the walls. Glass cabinets encase a carved wooden walking stick, the artist’s diaries, or seemingly unrelated etching collections borrowed from mainland Australian public and private collections. I don’t really understand why the forced distanciation is so key in this exhibition: there is already the misty cloak of Anglo-Celtic amnesia at play on this island of First Nations, lutruwita.

I have learnt in my two months as a visitor to nipaluna in muwinina lands that nothing in the settler-colonial imaginary is anodyne. Here, the English language acts as a comforting sign to the Anglo-Celtic majority that their intellectual heritage is centred, that palawa/pakana presence is hidden in plain sight/site of this exhibition. Nowhere in the exhibition is any palawa kani language displayed, and nowhere in the exhibition is any mention at all of the rampant genocidal campaigns that were early settler colonial life in these First Nations lands. Instead, there is a nostalgic tone to the display of portraits and accessories that have not survived the test of time well. An 1830s rusted iron bed reinforces the social history thrust of this exhibition, like the door at the entrance, salvaged from the ruins of empire.

The most visually interesting display, the only room not shrouded in darkness in Paradise Lost, is evocatively titled ‘The Boudoir’, a term that doesn’t get used in French anywhere near as much as in English. This beautifully decorated small room includes a faux fireplace, ornate mantlepiece and windowsills, colourful displays of preserved butterflies, beetles, glass and stoneware. The exploitative logic of this display, however, is the fact that these works, dating from a ceramic fragment from ancient Assyria in 650 BCE to a Song dynasty Yingqing bowl from 960–1279 CE, among many other ceramic shards, coins and glassware, are all significant to bygone human civilisations located outside lutruwita. None are mentioned by Wainewright in his diaries but are a curatorial imposition to evoke the atmosphere of the convict artist’s former Parisian life before arriving in the penal colony. This deceit is unforgiveable to me, particularly as the random assortment of significant material culture doesn’t provide a richer reading of the actual artworks assembled in the other rooms.

I can’t go on here without considering the title. Whose paradise? Whose loss? When did carceral aesthetics take over museum practice in lutruwita? These questions among others kept running through my head as I walked through the large, sprawling monographic exhibition. Dedicated to an English convict-artist, Paradise Lost is another attempt by conservative art museums in Australia to position the problematic foundational white artists of their colonial collections as recoverable to a cosmopolitan, intersectional art history. Great pains are taken to argue in wall labels for the value of Wainewright in Australian art history. He is apparently unjustly derided as a wealthy artist, essayist and poet before embroiling himself in fraudulent scandals and crimes that led him to lower his station to that of a convict assigned to Van Diemen’s Land. His portraits of the Hobart elite are contrasted with the material culture of major ancient civilisations and English painters of the period (John Linnell, Thomas Phillips, Henry Fuseli, John Milton and William Blake), though their inclusion fails to validate this focus on Wainewright.

Displays of contemporary and historical art that have a resolutely decolonial context are evident at the state art museum in the work of Julie Gough, Vicki West and Lola Greeno among others. But I want to focus on this particularly dangerous exhibition logic of settler colonial amnesia being romanticised. The antidote to the elegy to carceral aesthetics seemingly lies further north on lutruwita, in palanwina lurini kanamaluka (Launceston). I recognise that my reading of the two art museums is coloured by QVMAG’s art and design collection being located entirely in the Royal Park buildings, with TMAG’s art collection adjacent to social history displays. Both feature a more conventional display on the survivance of palawa/pakana cultural practice, relying heavily on the social history museum as a remediation of ethnography’s faked objectivity from presumed white majority audiences.

Herself and the new art collection hang offer a much richer and complex perspective on the troubled history of settler colonial presence on First Nations lands, at the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (QVMAG). Confidently shifting the northern art museum’s curatorial framework “away from the colonial and federation narratives” towards more intersectional ones, both exhibitions are evidence of a soul-searching that is bearing real fruit. Statements about wanting everyone to feel they belong have translated into nine new commissions and nineteen new acquisitions from artists as celebrated as they are diverse in medium and concern: Lola Greeno, Julie Gough, Ray Arnold, Ricky Maynard, Vicki West, Dave Gough, Mish Meijers, Tricky Walsh, Rodney Pople and Mandy Quadrio. An intergenerational array of works by living women artists—particularly incredible shellwork, fibrework and conceptual works by Greeno, Gough, West and Quadrio among these—is interspersed with more historical works, completing the regional art museum’s more complex engagement with the contemporary moment.

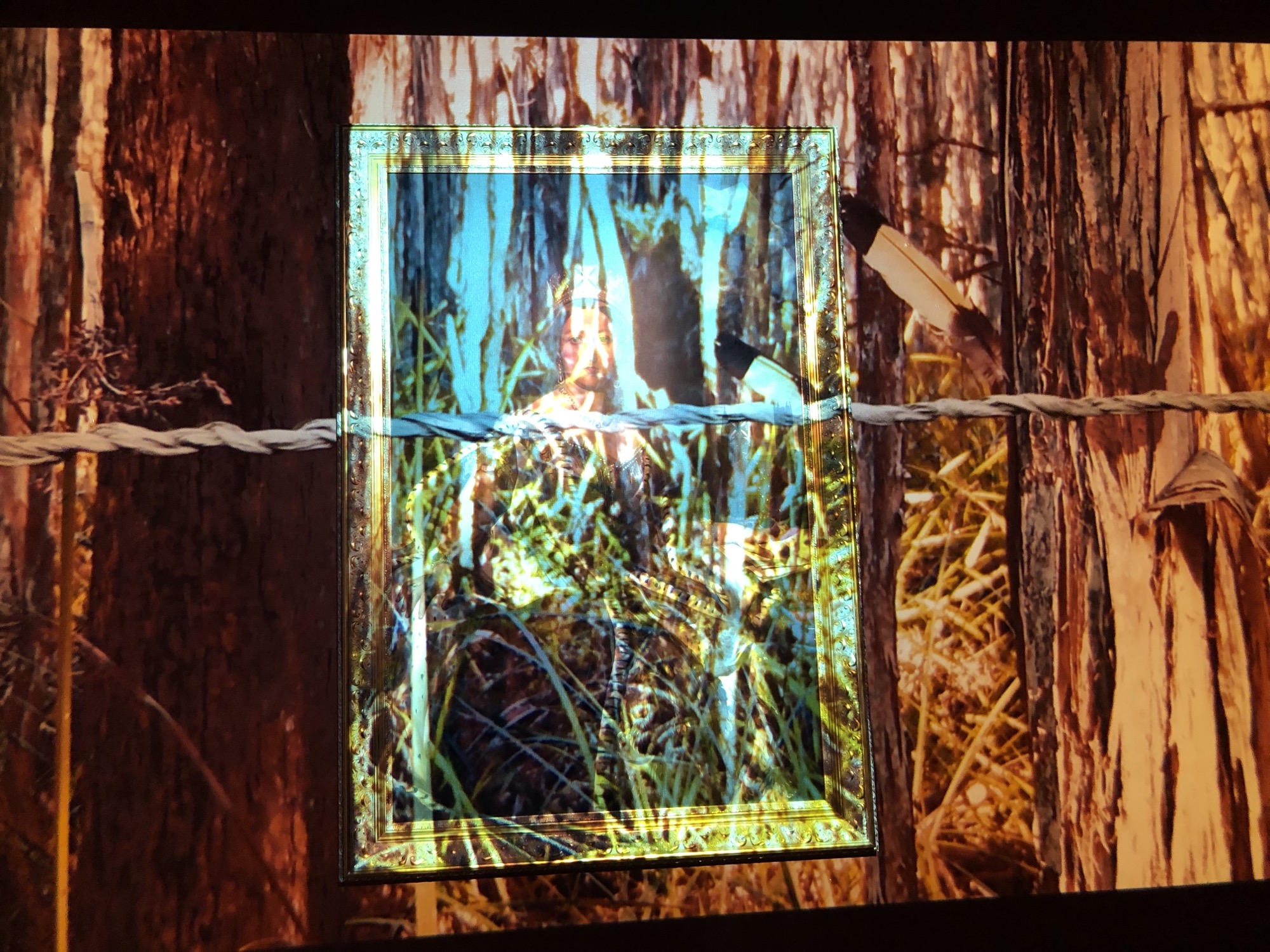

My favourite artwork on display brings the overbearing portrait and namesake of the regional art museum into sharp relief. The commission by trawlwoolway artists Vicki West and Dave mangenner Gough with Daryl Rogers, taymi ningina never ceded (2021), is an impressive fourteen-channel video installation across the entrance stairwells of the Royal Park galleries. The artists portray fibrework moving back and forth between generations, across the many screens mounted on the deep ochre coloured gallery walls. The work taymi ningina never ceded is a work of welcome, of assertion of palawa/pakana sovereignty, and of connection with ancestral generations and future generations. It is a marker of the precolonial history of the gallery site itself: a firestick-farmed landscape of tea-tree forests, where palawa/pakana peoples thrived. In the artists’ statement, “the smoke drifts across the surface of a reproduction of Robert Dowling’s portrait of Queen Victoria, which hung in this stairway for many years”. Literally a remediation of the settler colonial presence, recent as it is, overlaid on First Nations territories and ways of relating, this work, and through it, QVMAG, resists the so-called culture wars of conservatives that seek to entrench race hierarchy and white cultural amnesia across Australia.

Reflecting best practice nationally and internationally, Herself and the new art collection hang offer difficult histories and culturally distinct perspectives for audiences, built carefully through consultation and collaboration. Well-lit, generously spaced, the works in both exhibitions range from depictions of urban life, portraits, ceremonial regalia, landscapes, fauna and flora, particularly endemic and extinct species such as the thylacine and southern quoll, to more conceptual meditations on the watercourses across northern lutruwita. The spacing and relationships between works across these two exhibitions demonstrates sophisticated readings of the histories of lutruwita, and the problems of the redress of art collections built by previous generations of curators in a regional art museum. I commend the placement of celebrated palawa/pakana artists throughout the colonial landscapes and contemporary works by non-Indigenous artists, which enable Indigenous perspectives to bear on the genocides, intergenerational traumas, but also the joys and mobility of contemporary urban and regional life.

Dr Léuli Eshrāghi (Sāmoan/Persian/Cantonese) is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, curator and scholar working between Australia and Canada. They are Curator of the 9th TarraWarra Biennial (2023) and co-editor with Camille Larivée of D’horizons et d’estuaires: entre mémoires et créations autochtones (Éditions Somme toute, Montréal, 2020).

Paradise Lost: Thomas Griffiths Wainewright

Curated by Jane Stewart, Principal Curator (Art) with Peter Hughes, Senior Curator (Decorative Arts).

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

11 June – 3 October 2021

Herself and Visual Arts and Design collection hang

Curated by Ashleigh Whatling, Senior Curator (Visual Arts and Design)

Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery

1 August 2021 – Permanent