Phuong Ngo, Nostalgia for a Time That Never Was

Amelia Winata

I bet you didn’t know that there was more than one Treaty of Versailles. In the eighteenth century, the French signed no less than seven. The best-known Treaty of Versailles—the one that marked the end of World War I—was signed almost two centuries later. It should really come as no surprise, given that the French were peak colonising around the eighteenth century and the treaties were methods of asserting French military influence. And when they weren’t colonising, the French were at least scoping out their prospects. One of the first treaties of Versailles was made with Lord Nguyễn Ánh in 1787, who offered France a few concessions in Vietnam as part of the deal. Without going into the intricacies of why the treaty was signed (there was inter-familial feuding involved), suffice to say this was the first time France dipped its toes into Vietnam, giving them a taste for making it their own a century later.

Phuong Ngo’s current exhibition Nostalgia for a Time That Never Was, opens on to a French dumbwaiter from 1790—a three-tiered, stained wooden item of furniture used to present food and drinks. As such, the exhibition begins with an explicit reference to the French colonisation of Vietnam. This installation, which was produced with Ngo’s collaborator Hwafern Quach, is titled Ever Altered (2020–) and is a meditation of the early colonial days of French/Vietnamese “relationships”. The dumbwaiter is covered with a vast array of cognac bottles that have been silvered, resulting in a mirror effect. This allusion to mirrors and, therefore, the Hall of Mirrors where the Treaty of Versailles was signed, seems literal on paper. But, in practice, it works. Tiered like an elaborate wedding cake, the dumbwaiter presents itself as a leftover remnant of a fabulous aristocratic court party, preserved in time.

I doubt Ngo is concerned with recreating the greatest parties in history. Nostalgia for a Time That Never Was is part of Ngo’s ongoing investigation into the history of colonisation and war in Vietnam and the enduring effects that this trauma has had upon the Vietnamese population. To be sure, the Vietnamese have been repeatedly fucked over. In addition to French colonisation (from 1858), the Vietnam War (1955-1975) and the fallout of the war—which included traumatic migrations and ongoing racism experienced in adopted countries—Vietnam was also colonised by China not once but four times prior to French invasion. In 1981, Ngo’s parents and older brother came via boat to Australia following the Fall of Saigon, becoming part of the single largest migration of Vietnamese people to Australia to date. Ngo was born in Australia but, as is the case with inter-generational trauma, the effects of his family’s experiences have been passed down to him. Nostalgia for a Time That Never Was is a sprawling exhibition that occupies the Substation’s ground floor thoroughfare and four galleries that branch off it. A video work also played in the large first floor gallery until 21 May. This being Ngo’s PhD exhibition, it is replete with a depth of thinking about the Vietnamese diaspora, which he represents through a dizzying range of mediums—archival imagery, film, painting, photography, installation and ready-mades. The constant switching of mediums and historical references does not feel incongruous though. It simply reflects the complexity of his and his community’s experiences.

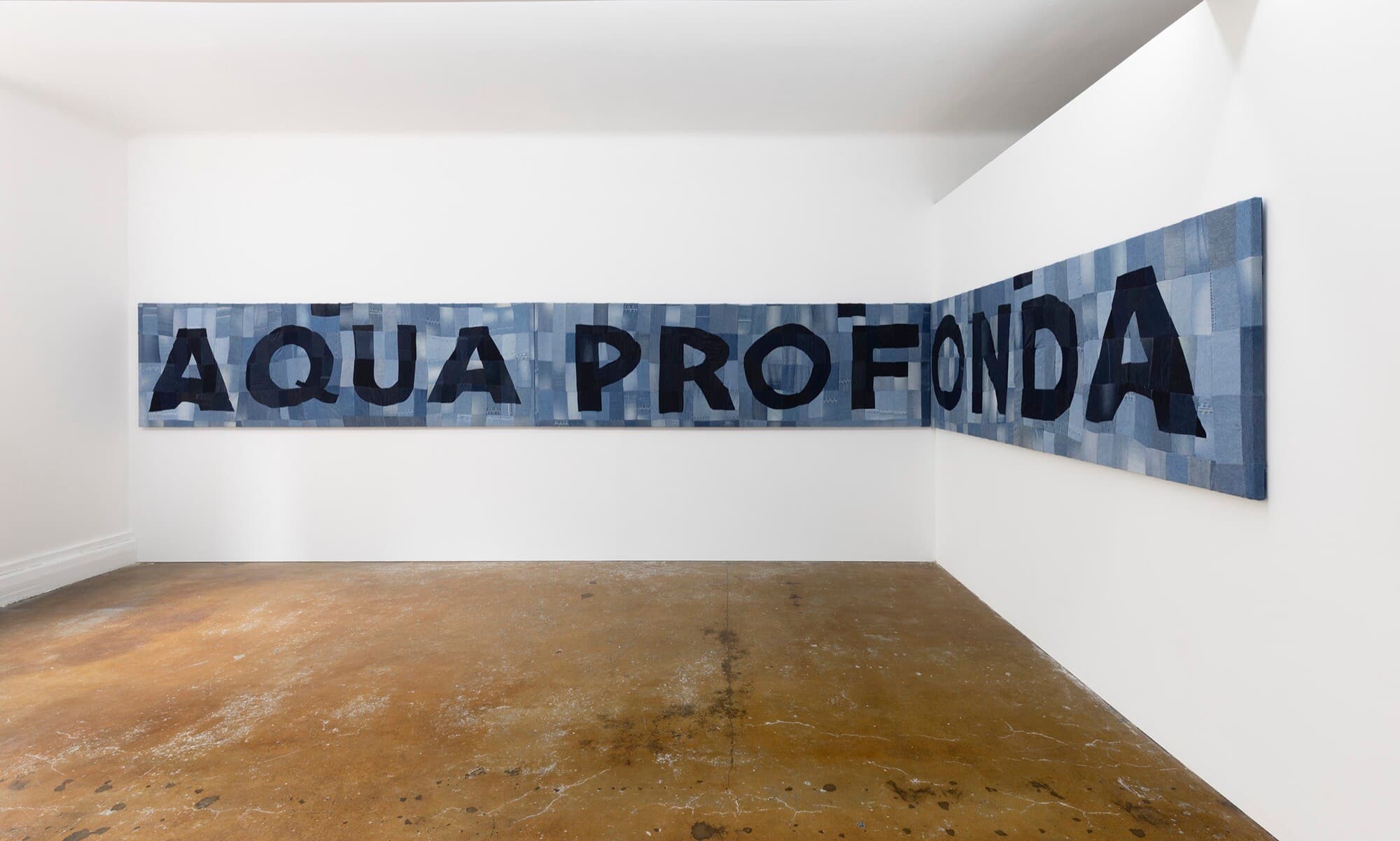

Having said that, Ngo employs a very astute formal tactic to bring a sense of cohesion to the exhibition, which is that he has painted every gallery in the same azure blue. I later learn that the paint is manufactured by Haines and is called Australian Standard Oriental Blue. With this additional information, what seemed like a simple aesthetic choice in now extremely loaded. In 2016, the Obama administration outlawed the use of “oriental” in federal law. But while the word was recognised by the United States government as a slur towards Asian Americans, it nonetheless continues to be brandished by big companies to sell products. In the case of the Haines paint, Ngo suggests that it screams, “look, I’m a model minority!”, as though standard orientalism is a thing: or, even worse, that a standard Australian orientalism—a kind of regional dialect—is a thing. As an Asian-Australian myself, the term oriental has always offended me because it is so generic. I am reminded of oriental flavoured two-minute noodles, a non-descript flavour co-opted by a white multi-national (Maggi) for the tastes of predominantly white consumers. Anti-Asian racism is naturalised through consumer products. Used throughout the exhibition, the paint prompts viewers of Ngo’s agenda, reminding them that racism is alive and well and that there is a lineage between his ancestors’ experiences of racism in colonial Vietnam through to Vietnamese diasporic experiences today in Australia.

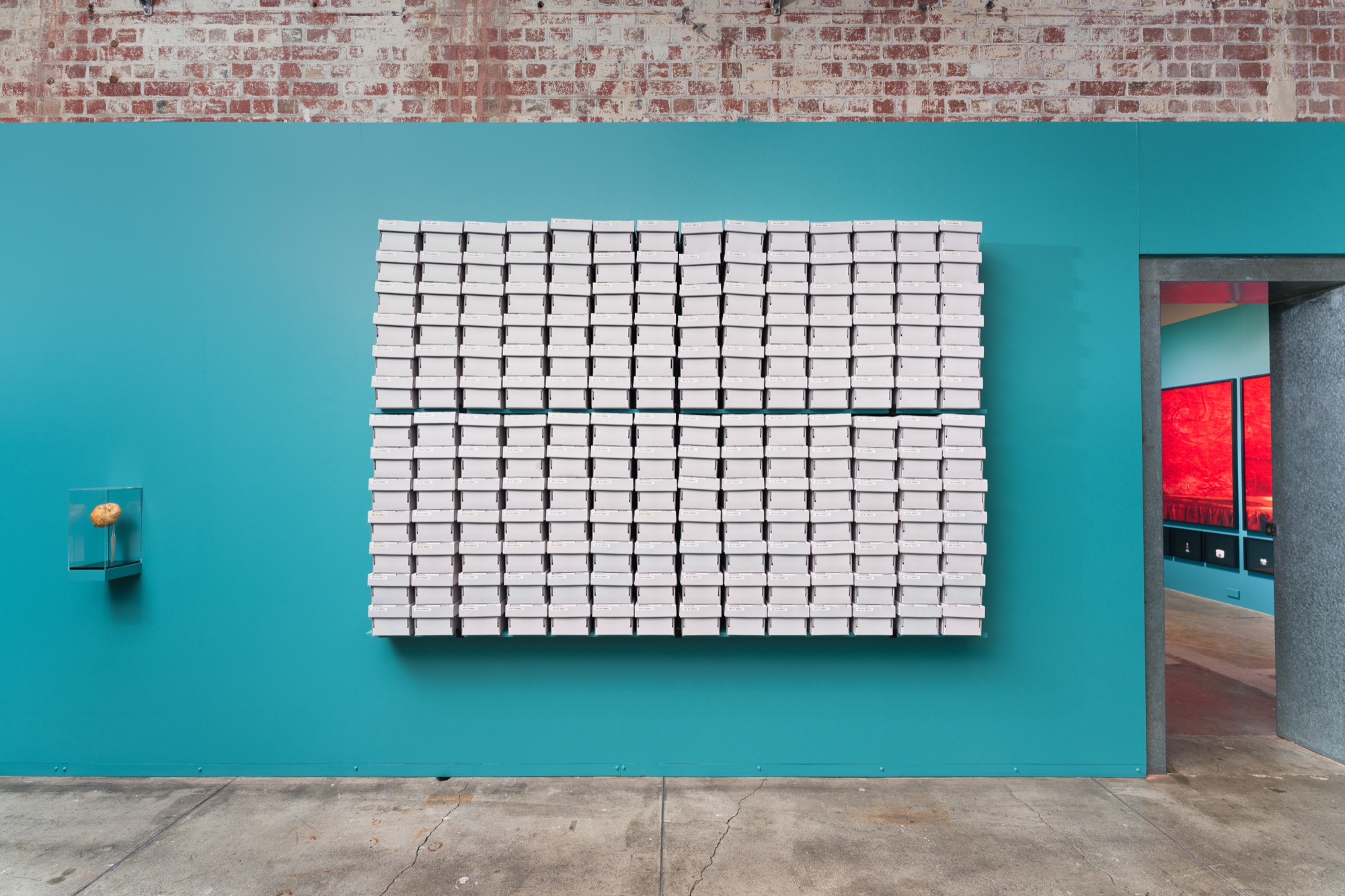

As we pass the readymade dumbwaiter, the viewer encounters Ngo’s answer to the archive. In recent years, plenty has been written about the use of archival material to re-evaluate history as multi-valent rather than singular (Okwui Enwezor’s 2008 Archive Fever looked at this in depth), but Ngo suggests that archiving contemporary objects is perhaps an even more effective method of beating the imperialist model because it creates new material made from the perspective of the colonised subject. The Bullhorn Research Centre (2020–) sees Ngo preserve and archive bullhorn cakes—the Vietnamese version of a croissant introduced during French colonisation—made by Vietnamese bakers in Sydney and Melbourne—literally preserve and archive them just as archaeologists would ancient specimens. This process allows Ngo to map the wide-reaching effects of colonisation upon Vietnamese populations as well as the geographic spread of Vietnamese migration in Australia. Each bullhorn cake has been left out to dry and then painted with varnish. It is tagged with the date, the location of its purchase and a unique identifying number and then packaged in archive-quality paper and an archival box. One bull horn cake is on display in a Perspex case, as though this traditional form of presentation legitimises its place as an archive piece. Next to this specimen, a collection of 182 white boxes line the wall—the entirety of Ngo’s bullhorn archive to date.

Unable to actually see the specimens, the viewer has little choice but to believe that the rest of Ngo’s bullhorn cakes are indeed housed in these boxes. Though there is just as much of me who thinks that the boxes are empty. Spotlit to the point of theatricality, Ngo layers a sense of the artificial over the work, daring his audience to question the boxes’ contents. Are these the authentic specimens or just place holders? I use “authentic” as a provocation. This is because the logic of authenticity plagues Asian people, who are continually called upon to prove they are real Asians. When used in relation to non-European cultures, the word authentic usually implies that these cultures are real only if they have not evolved past a certain historical point—usually the point of pre-colonisation. The conflation of stasis with authenticity has been historically perpetuated by Western enlightenment inspired museums. Writer Shimrit Lee has observed, for example, that natural history museum dioramas “give the impression that these cultures no longer exist or that they exist in a different historical time period, and there is no possibility of a shared humanity or connection between visitors and people whose cultures are on display”. Where western cultures have been allowed to evolve in line with the forces of global capitalism, Asian cultures have been expected to stay in their lane, to remain the chaste virgin ready for the picking by white consumers. Hybridity? Forget about it. Even the bullhorn cake, having evolved as it did from the croissant, only sets itself up to fail the authenticity test. In refusing to provide any proof of the bullhorns’ existence in the space, Ngo also refuses to justify what he says is real.

Given this critique of authenticity as a form of imposed statis, there is a very conscious impermanence across the exhibition. Throughout, gladioli (commonly placed at Vietnamese ancestral shrines) wilt in trench art vases—a vase made out of an artillery shell left as a remnant of the Vietnam war. With their stems yellowing and their buds dehydrated, these flowers register the duration of the exhibition and threaten to completely rot before the show closes in July. On the opening night and during artist talks, cognac was served in the glasses that now sit around the dumbwaiter in the work Ever Altered. The idea being that the aroma of the cognac would permeate throughout the exhibition space. An emphasis upon impermanence seems to be an important method of resistance for artists tackling colonisation in their work. Only recently, James Nguyen encouraged viewers of his installation as part of The Nguyễn Collection of Anglo-Australian Arts (2022), to sign their names on a colonial bucket, thereby desecrating the (white) sacredness of the specimen. Nguyen and Ngo are in fact friends, and Ngo recently gifted a bullhorn cake from his archive to Nguyen, proposing that gifting may be another way by which archives can remain decentred.

The almost poetic logic of Ngo’s archival boxes is balanced against just as many jarring images that depict the horrors perpetrated against Vietnamese people. In Lost and Found (2020–), Ngo has overlaid photographs of Notre Dame in Paris burning in 2019 with archival postcards of a replica Notre Dame built in Saigon by French colonists in 1880. You read it correctly. When the Paris Notre Dame burned down, people pledged one billion Euros to rebuild it in just one week, a demonstration of the sway that white imperialism has. Meanwhile, tucked around the corner as though to protect youthful eyes, two portraits—one of Marie Antoinette and one of Louis XVI—are overlaid with postcards depicting the severed heads of North Vietnamese pirates. These heads are positioned in place of the monarchs’. The guillotine, used to execute Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, was viewed as a humane method of execution. Fast forward two centuries and French occupiers demonstrated an incomprehensible level of inhumanity by decapitating these pirates with swords and machetes.

It gets even rougher. Upstairs I watch A World Vision (2022), four minutes and 16 seconds of pure discomfort. It is an 1889 film by Gabriel Veyre that shows a French mother and daughter duo standing atop steps and throwing coins into a throng of Vietnamese people who scramble to grab what they can. Ngo has inserted a soundtrack, Mary Poppins’ Feed the Birds, creating an uneasy juxtaposition between this childhood favourite and the horror playing out before my eyes. The title, A World Vision, clearly refers to the white-run aid organisation (that had me voluntarily starve myself for 40 hours once a year between the ages of ten and fifteen), thereby highlighting the way in which charity often collapses into imperialism.

Ngo has said that he makes works first and foremost about himself, his family and his community and that he wants to make young Asian artists feel welcome. If white audience members want to engage with his work, that is fine, but he is not going out of his way to make them his target audience—he does not try to educate a white audience or make them feel comfortable about their whiteness. This is evident in the titular installation Nostalgia for a Time That Never Was/Internalised Racist Paintings (2022–), which takes the piss out of white artists. The installation contains three hard-edged abstract paintings that dominate the space—two on the wall and one that follows the 90-degree angle of the lower wall and floor, highlighting that the paintings are in fact comprised of panels that in turn reveal themselves as repeated composites of two rectangles. One is the aspect ratio of Co Vang—the now defunct South Vietnamese flag—and the other is the aspect ratio of the Australian flag. Ngo has then deliberately packaged these paintings up to replicate the neat aesthetic of modernist abstraction, thereby having them masquerade as the forms of the white imperialism he critiques. A few artists immediately come to mind: Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella and, of course, Jasper Johns, whose American flag painting Ngo’s works might very well riff off (although Johns was not uncritical of American imperialism).

The rest of the installation is comprised of two lightboxes. One contains an archival image of the American flag and Co Vang, the other an image taken at the January 6 Capitol riots showing Co Vang being flown. Co Vang has traditionally been flown by Vietnamese immigrants, who fled at the end of the war, to distance themselves from communism, but many of these immigrants formed an important constituency of Trump supporters—a fact widely put down to Trump’s anti-China stance. It would seem that a conflation of nationalism and freedom has given rise to these extreme right-wing tendencies. Indeed, there is a sense of amnesia amongst older immigrants, who forget that systems such as Trump’s would not allow the mass migration that allowed them to flee Vietnam in the first place.

Nostalgia for a Time That Never Was is an unequivocally beautiful exhibition, in the sense that it looks good. And while many of the visually pleasing formal aspects have an uncomfortable underside (the oriental blue, the use of museum-style lighting), there is also an immense sense of generosity at play. To be sure, simply because a work takes trauma as a central subject matter does not mean it must replicate that trauma through its form. Given the history of white male artists who have relied upon a spectacle of disaster—Andy Warhol, George Baselitz—Ngo likely consciously avoided it. More concerned with including his community than educating the white viewer, Ngo understands that a preserved bullhorn cake carries just as much gravitas as any visual representation of death or anguish.

Amelia Winata is a Narrm/Melbourne-based arts writer and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne.