1:250 model of Monash College (completed 2021). Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis.

NMBW Architecture Studio, From No. 2071 to No. 9401

Moyshie Elias

A week ago, I celebrated my birthday in Rome with a visit to the Pantheon followed by a balmy evening drinking Birra Moretti amongst beautiful Mediterranean types at Piazza Testaccio. La dolce vita. Now I’m on Little La Trobe Street, standing in Cache, a dusty old office-turned-gallery, and it’s four degrees, and I’m surrounded by gaunt architects with bloodshot eyes guzzling free claret from plastic cups staring at architectural models made of balsa wood, box board, card, and metal wire. It’s not a comedown from the Eternal City. Not at all. We’re here to celebrate the opening of From No. 2071 to No. 9401, an exhibition showcasing three decades of work from the lauded Fitzroy-based NMBW Architecture Studio, run by Lucinda McLean, Marika Neustupny, and Nigel Bertram. The show is a selection of over 140 models and maquettes, accompanied by a catalogue and a fresh NMBW website link, both produced by every tasteful Melbournian’s favourite designers, Ziga Testen Studio, with graphics by Stuart Geddes.

Photo by Peter Bennetts.

I worked at NMBW for two years as an architectural graduate, from 2018 to 2020, so I know most of these models well. After leaving the exhibition space, I head to the bar, where I bump into my ex-Director, Nigel Bertram (the “B” in NMBW and Practice Professor of Architecture at Monash University). “Nigel, I just got back from Rome,” I say. “I visited the Pantheon.” He laughs. “Wow, the Pantheon … That’s great, Moyshie,” he says. “That’s like, the best building ever. The big opening at the top, it’s fantastic.” This is peak Nigel: excitable, plainly spoken, and architecture obsessed. I think of a joke which compares the number of Roman slaves who must have died during the construction of the Pantheon with the number of fingers that must have been cut during the making of NMBW’s models. I think better of it.

Instead, I ask Nigel what it feels like exhibiting NMBW’s work in the space that was once office to Edmond & Corrigan, the legendary practice where Nigel cut his teeth as a graduate. He admits that whilst he was initially hesitant, ultimately, it felt good to show work in the space once commandeered by his former boss Peter Corrigan, who many consider to be the Grand Poobah of Australian post-modern architecture. As Conrad Hamann writes, Corrigan embraced Australian architecture in all its complexity and contradiction and “totally rejected the Australian cultural cringe.” This thoroughly postmodern streak also runs proudly through NMBW’s work, where humble Australian building details are re-imagined in the spirit of Kazuo Shinohara. They aspire to the finesse of SANAA and the elegance of Lacaton & Vassal. They’re driven by the doggedness of Roy Grounds and the DIY verve of Brian Klopper. The firm’s overall architectural style could be described as “Mongrel Cute.”

Photo by Peter Bennetts.

I remember a typical day in the NMBW studio in 2018. An exasperated Nigel speaks with gentle intensity into a Telstra landline handset from 1997. “It’s the oldest fucking building product in Australia,” he says. He is arguing with a building surveyor who won’t let him specify corrugated iron (the oldest fucking building product in Australia) without the necessary fire risk assessment certificates. Red tape gone mad! Nigel slams down the handset. The handset slam is one of his trademark expressions. But to anybody who has met Nigel, both the swearing and the slam are easily understood as totally benign reminders that he cares a lot about architecture. To his right, a couple of metres away, an international student, Giancarlo, an interning model-maker from Italy, pauses briefly before delicately scoring another piece of balsa wood. Giancarlo is working on a model for the University of Melbourne’s new Student Precinct—one of the 142 models now being shown at Cache.

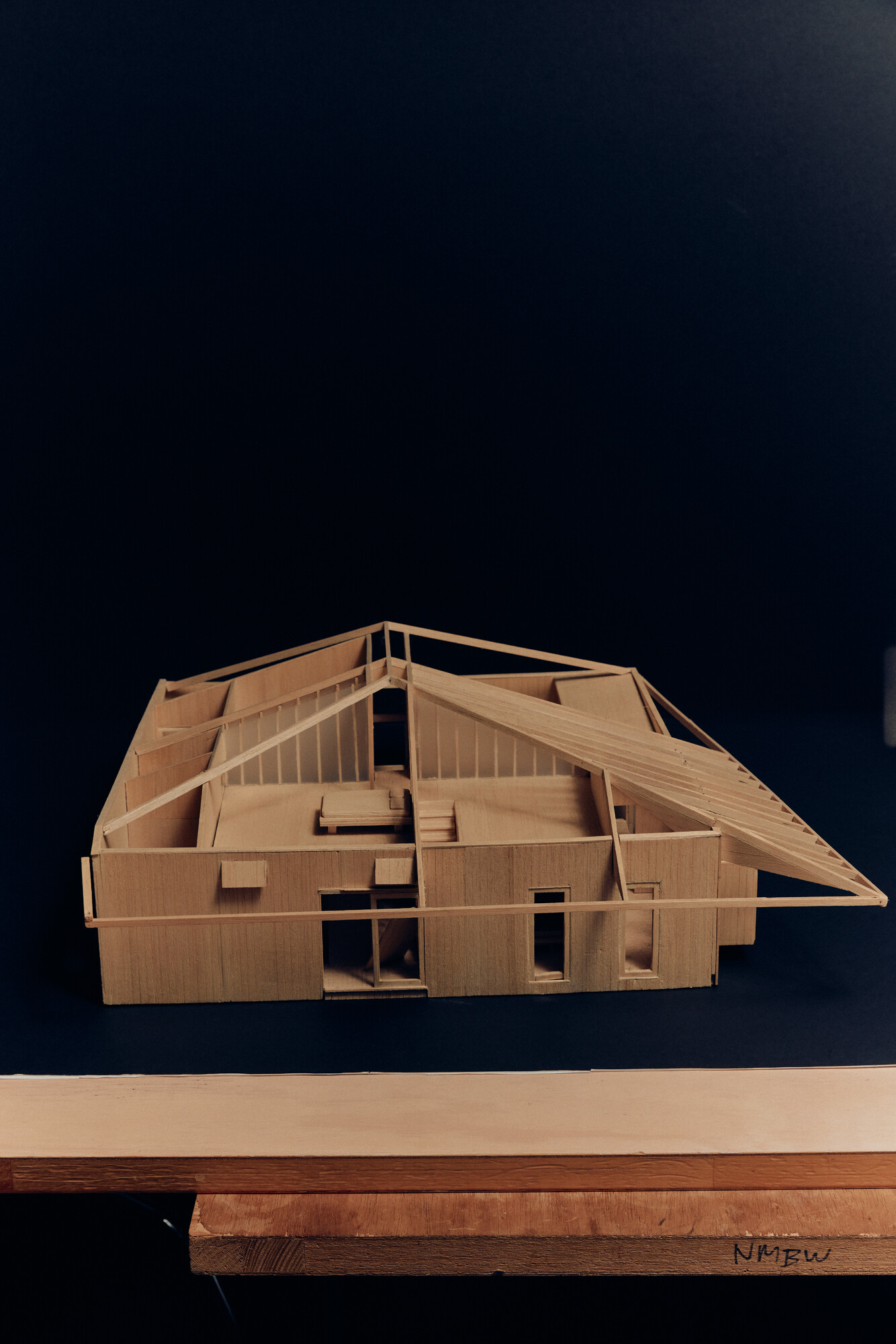

The models are displayed on the bookshelves and walls of the old Edmond & Corrigan Library (keen punters can read more about the old Edmond & Corrigan haunt in an excellent piece by Michael Spooner). The exhibition space is halfway between a dank terrace house attic and an industrial nightclub for tiny people. The models vary in scale and neatness. They appear delicate from afar, but they’re rugged enough to be handled. I lift the roof off the 1:50 balsa wood model of the Sorrento House (2007) to reveal a radial array of rafters reminiscent of the roof structure of Shinohara’s Umbrella House (1961). My partner looks at me with panic, as if I’ve just picked up a sculpture in a gallery. “What?” I say. “You’re meant to pick them up.” Architectural models are meant to be held, or at least moved around and viewed from a range of perspectives. Another shelf holds a 1:50 sectional model of the Frank Tate building at the University of Melbourne, prepared by an Irish student, Conor. I bring my eye right up to one of the four-centimetre-high doors and peek through.

1:50 model of the Sorrento House (completed 2007). Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis.

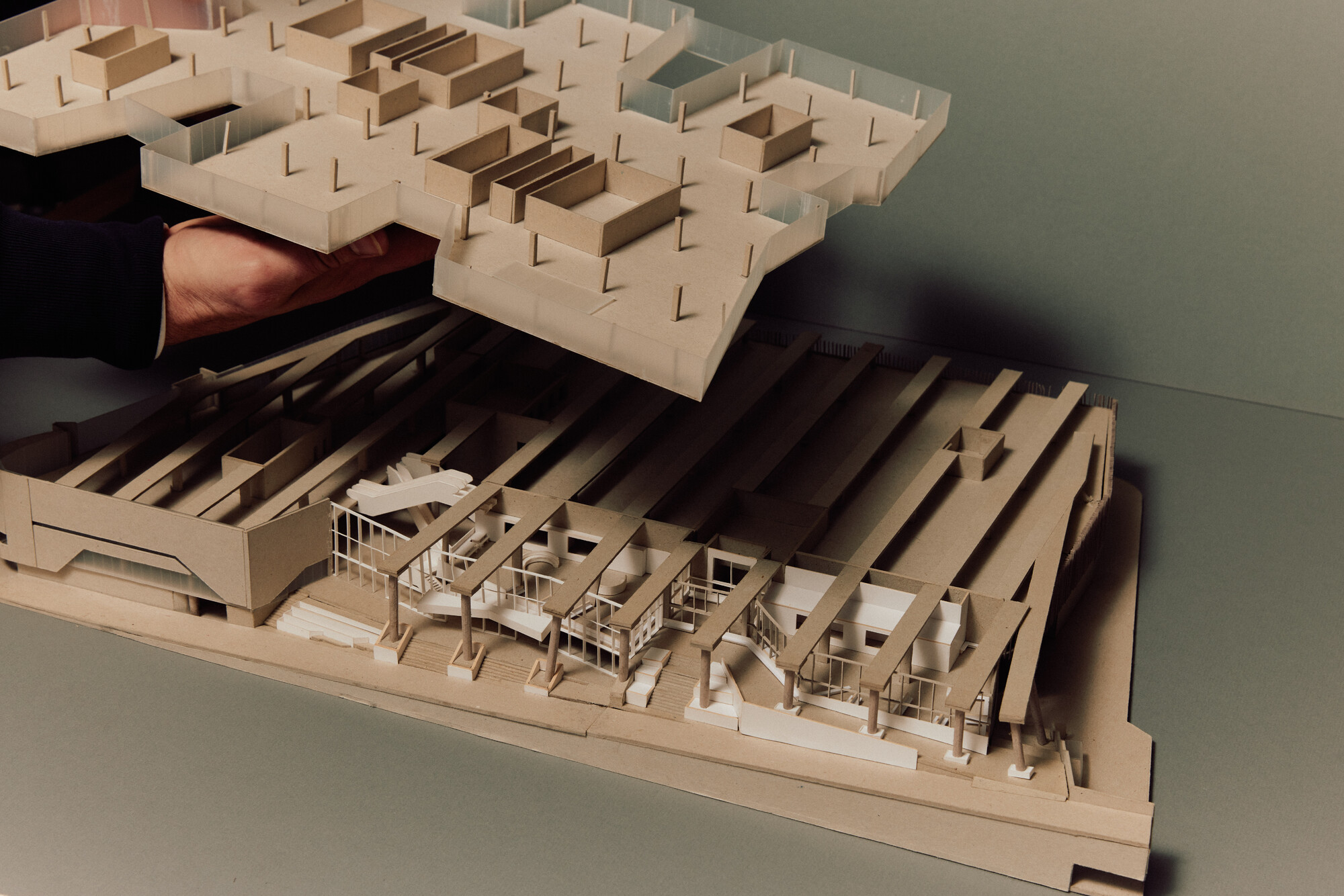

Back to 2018. To Nigel’s left, three meters away, is Marika Neustupny (the “N” in NMBW). It’s a winter morning and the dusty warehouse office on Kerr Street in Fitzroy is still warming up. Only five of us are in. Models are being made, spreadsheets are being confronted, PhDs are being written, building surveyors are being told off, and I’m furiously drafting a 1:5 detail of a log bench, which as the name suggests, is both a log and a bench. I ask Marika what sort of timber the log should be made out of. She corrects me, smiling, saying, “Logs are cut, not made.” I nod. It’s true: logs are cut from trees and benches are made from timber. Our conversation feels both Amish and Japanese. “Let’s do some research into local log people,” Marika says. The drawing is to be submitted to the builder in two hours. We don’t really have time for local log people research. Also, the log bench I’m detailing will be three meters long—fairly small in the overall scheme of the project, the gigantic Monash College Campus at 750 Collins Street. Correspondingly, it will account for a tiny portion of the project’s budget. But at NMBW, every log matters. The log concept was never translated into model form—if it was, it would have been a twig. Instead, it made the leap straight from detail to build, nay, sourced and installed log. But the project which the log calls home does exist in model form.

Monash College (completed 2021) is one of a trio of projects, including the New Academic Street at RMIT and the University of Melbourne’s New Student Precinct, in which NMBW collaborated with old peers and patrons Lyons. I shudder looking at the 1:250 model of Monash College (I worked on the project). But, involuntary physical responses aside, I learnt more being thrown in the deep end on that project than I had learnt in my previous seven years in the field. Most of that learning was enabled by Marika.

1:250 model of Monash College (completed 2021). Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis.

Marika’s architectural lineage is formidable. She studied under Yoshiharu Tsukamoto (Atelier Bow Wow) at Tokyo Tech in the decade following the retirement of the great Kazuo Shinohara. Then, Neustupny went on to work for Kazuyo Sejima at Pritzker Prize-winning Japanese firm SANAA (who recently designed Sydney Modern). Along with being a director at NMBW, she continues working as an educator, and is chair of the National Committee for Gender Equity at the AIA. She is also very short. I will never forget her going toe-to-toe with legions of tall men in black puffer vests during the construction of Monash College. Like Neo vs Agent Smith, or Yoda vs whatever bigger and badder opponent Yoda fights, Marika fought impossible battles and often won.

At Cache, I move on to one of Marika’s favourite models, a neatly crafted white card version of the North Melbourne House (completed 2016, winner of the Harold Desbrowe-Annear Award for Residential Architecture, AIA Victoria, 2019). The model shows how the house curls up like a cat between two courtyards. The house is a masterful assemblage of little havens and lookouts. It’s a place where one can appreciate the pitter patter of droplets on galvanised steel roof, and observe the flow of water as it runs into gutters and downpipes. NMBW’s obsession with how we experience water is for the most part lost in their, well, dry physical models. We get an idea for form, volume, scale, and some sense of materiality. But we can’t, for instance, experience the North Melbourne House’s prized downpipe detail, in which rainwater harvested from the rooftop terrace feeds a birdbath in the front courtyard. This little architectural triumph shows how NMBW treats water droplets like characters in a Miyazaki film, all part of life’s adventure. That said, some view NMBW’s architecture as being less Spirited Away and more Picnic at Hanging Rock. A colleague once described their style as being like Wake in Fright if it were to be remade by Hirokazu Koreeda.

1:50 model of the North Melbourne House (completed 2016). Photo by Annika Kafcaloudis.

The white card model for the Point Lonsdale House (completed 2015) hints at NMBW’s keen engagement with Australian architectural history and its resident ghosts. The house is heavily influenced by Ballara (1907), the former residence of Prime Minister Alfred Deakin. Ballara is a rare example of a Federation bungalow which features a series of attic spaces spiralling upward via a steep and creaky stair. The building, with its two-tone facade, internal clutter, and general pokiness, is charming yet haunted (by the ghost of its ex-PM owner, a Spiritualist with a penchant for seances—perhaps this is what informed my colleague’s tongue-in-cheek remark about NMBW’s work channelling Australian colonial horror). At Ballara, as with several NMBW residential works, it’s all about the cubby-like attic spaces.

Another great NMBW attic space is in the Flinders House (completed 2021). The design process and construction of the house is documented in the practice-based research PhD of Lucinda “Bindi” McLean (the “M” in NMBW). Every Christmas lunch at NMBW involves a trip to one or more projects that have been through the practice. During my last day at NMBW, the whole office visited the Flinders House. I stare at a model of the project at the Cache show. Maybe I’m welling up, just a little.

Models of the Point Lonsdale (Completed 2015) and Flinders House (Completed 2021) installed at CACHE gallery. Photo by Peter Bennetts.

We arrive at the Flinders House on a hot day at the end of 2020. Bindi, the lead architect on the project, is showing us around. She’s being incredibly modest about it all. Jonathon Yeo, an NMBW veteran who spent a whopping eight years at the firm, chimes in every now and then. We learn of the project’s teensy budget, about how the owner/builder was great to work with, and about how the previous landowner was a fisherman who sold snapper on site. For the duration of my time at NMBW, Bindi had a wide range of duck egg colour paint swatches laid out on her desk. I didn’t understand why until I saw the Flinders House; the facade is painted in two perfect duck egg blues. The colours had been carefully chosen to match pieces of cladding salvaged from the demolished house. This isn’t captured in the white card model.

Bindi completed her Master of Architecture at the Städelschule in Frankfurt. She shares Nigel and Marika’s love of history. Bindi and I worked together toward the end of a residential build in North Fitzroy. In architecture, we have what is known as the “defects” period—basically a time when architects have to ensure the thing has been built properly. It is usually an entirely unglamorous period. I learnt quickly that an architect’s ability to perform well during this time is very much about ad-hoc detailing: thinking of quick, elegant solutions to mistakes. Bindi is an enthusiastic sailor, and her proposed solutions to many of the defects would be to make use of parts from the Whitworths or Ronstan sailing catalogues. Alas, no rope or pulley details made it into the exhibition.

Overall, From No. 2071 to No. 9401 is a nod to NMBW’s three decades of practice. It’s cool to see all the models lined up. The catalogue and the new website are great. But these things are all nothing without what’s outside of Corrigan’s old library: the immense body of work and more ephemeral offerings the NMBW family have contributed to the local architectural field in their first thirty years. It begs the question: what will the next thirty look like? In an age where commerce and construction run at breakneck speeds, there are obvious questions one could ask about the scalability of NMBW’s work. The firm has proven it punches above its weight where civic, education, and multi-residential projects are concerned. But I’ll leave it to the architecture world’s resident Marxists to keep discussing the issues related to money and labour, and how these doozies impact the procurement of architecture. Don’t shoot! … I’m a card carrying unionist.

For now, let’s celebrate the architecture of NMBW, which is born out of what Marika would often describe as “generosity.” A generous architecture aims to bring people closer to the cultural and ecological lineages of a site; closer to construction materials and their origins; and perhaps most importantly, aims to foster closeness amongst people. Of course, there is a requisite slowness to achieving all of this. Fostering lasting relationships takes time. Getting to know unfamiliar sites takes time. Manually making physical models takes time. Arranging thirty years’ worth of those models in a hip new gallery takes time. But Rome wasn’t built in a day.

Moyshie Elias is a practising architect currently working at NH Architecture in Naarm/Melbourne.