Mutlu Çerkez: 1988-2065

Nicholas Tammens

The exhibition Mutlu Çerkez: 1988 – 2065 and its accompanying monograph form a long awaited eulogy to an artist whose influence has remained largely unacknowledged since his unforeseen passing in 2005. It would not be conceited to say that the format of the exhibition was fated by the artist, but there is a general feeling that it comes as a late arrival. As Justin Clemens once pointed out, Çerkez's work explored exactly these “vicissitudes” of determination that are latent within the life of any artist—how art history and the popular consciousness segment an artist's life into periods, gathers together all the matter from its orbit, and simplifies it at its termination. Introspection and retrospection were inherent to the task that Çerkez had set himself in making his art. There was a burden to it, a weighted and incredibly sad vision of labour that brought the serial demand of the production line into being with the banality of life.

This is not the fantasy of Çerkez's work. On the contrary, it is where it once drew and continues to draw its acerbic realism. Çerkez described his project and its inspiration better than anyone else:

probably the most beautiful, poetic and moving moment I have had while looking at art and, yes, probably the most inspiring, was as an art student looking through a book on de Chirico and thinking I was looking at a metaphysical painting from about 1915 and then realising that it was dated 1975.

This moment led to my idea to repeat all of my work at a later date. I began to title each of my works with a date from the future that would fall during my possible lifetime. I would undertake to repeat each work in some way on its particular date. Every work would reappear at some later point during my life's work. My work would not evolve, or at least the gradient of its evolution would be flat. It is a system where I can consciously fool myself that all my works are mature works. And working within this system I would, in fact, objectively use my own life's work as its own subject matter.

The duplicate dating format underwriting this system informs the basis of the exhibition at Monash University Museum of Art. It does so with good reason. None of the works included in the exhibition fall out of Cerkez's system and the curators are attentive to an attempt to present cohesive movements in his work. There are tragic omissions, but the exhibition's monographic catalogue performs well in its stead, detailing the breadth of Çerkez's career with the historical import and anecdotal hinges that are so crucial to understanding a body of work that incorporates its own gaps, losses and imaginary duplicates. We learn of the loss of work to an airport fire, paintings indexed as “location unknown”, and the destruction of art by the artist himself.

One work that does not appear in the exhibition but appears in the catalogue (listed as “destroyed”—but, if I am correct, remains at least partially complete in the back of Çerkez's media file at Anna Schwartz Gallery) is Çerkez's series of coins that he minted on his stove in Sunshine in the late 1980s. They form an emblematic work for Çerkez, predating his earliest self-portrait on canvas and signalling an interest in the function that portraiture serves within a social history of art, as well as Çerkez's own coming oeuvre. Representation has long had a use-value in maintaining the sovereignty of state powers, be it in the mastery of court painters or the ascription of currency to the control of the head of state. In Çerkez's series, this meaning is carried through to another end. Beyond its will to provide the pith of meaning conflated between art and commodity, it draws attention to the perceived autonomy, or indeed sovereignty, of the artist. This view maintains that there was an ideological shift between the late 1960s until the 1980s, in the way that the West produced and consumed art—with the influence of movements in conceptual art, feminist art practices, performance art, etc., as well as a broader confluence that included entertainment, commodity culture, celebrity and the media. The old myth of genius was enveloped by a performative body, recasting a perception of the autonomy of the artist as sovereign power: as the prescriber and referent of meaning. Çerkez himself once joked about the power attributed to the artist once they acquired the status of a proper noun—a “Picasso”—maintaining a suspicion towards its resulting implications. Çerkez's work centred on this as a problem, continuing to function by possessing it as a drive: taking the total “life” of the artist as its referent.

Within his lifetime, the Australian art historian Mary Eagle commented that “Çerkez seeks to control every aspect of his relation to the world”. The problem now, in surveying the work of an artist who took to their work with such control, is just how this is to be attended to in making exhibitions without the artist's authority—as has proven to be the case with artists such as Michael Asher. In the best scenarios, the answer may lie in a transferral of power from artist to estate. The task for the curator becomes one of either animation or conservation of spirit, resting on belief—a theological leap—that takes us back to the etymology of “curator” and its founding as a vocation in the church. Such a belief maintains that what one is doing is in line with the perceived wishes of the artist. It is only by holding to this position with certainty that MUMA's team of curators, along with Marco Fusinato, Michael Graf, Stephen Bram, Rose Nolan, and the necessary assistance of the Çerkez family, could see this show through to completion in a way that we can at least sense to be attendant to the artist's own desires.

This is congruent with the successes of the exhibition, which lies in its moments of brevity and absence. The beginning galleries, showing a limited number of works, engender the feeling of the elegiac that Çerkez represented throughout his career, long before his passing. There are works that have not been sighted in years, for instance, the three digitally printed canvases of a broader series of eleven that reproduce still life drawings of Çerkez's mother's tablecloth, future dated by the time-stamp of home video (all untitled in Çerkez's idiosyncratic format). These are relieved by two understated paintings on canvas board, and Untitled 36891 (17 September 2065), 1990, which is likely the statement piece of the whole exhibition—a frieze of 111 small composition boards sitting atop a wooden shelf above eye level, each carrying a year from 1964 (the artist’s year of birth) to 2075; its line is punctuated by a still life painting of an uprooted young potato with the artist's signature inscribed in its surface, hung under the year 1990, the year the artist formally took the name of Çerkez. Its thoughtful installation perhaps makes up for the shortfall of impression in the much desired recreation of Untitled 12309 (30 May 1998), 1992, Çerkez's work that features an apiary of bees embedded in the window of the following gallery. I can't help but report that in seeing this work in 2018 it lacked the force that it held either at Anna Schwartz's Gallery, or in the venerable place of the imagination.

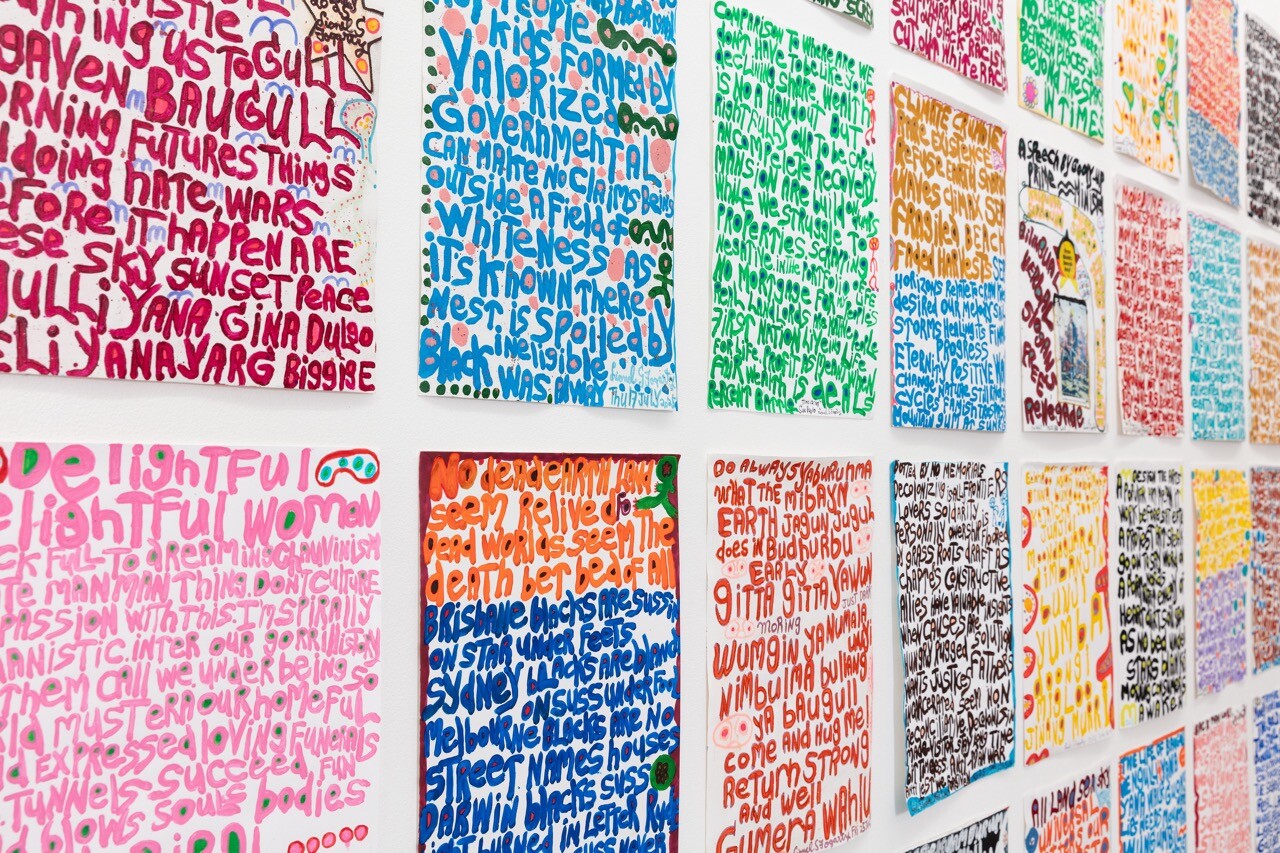

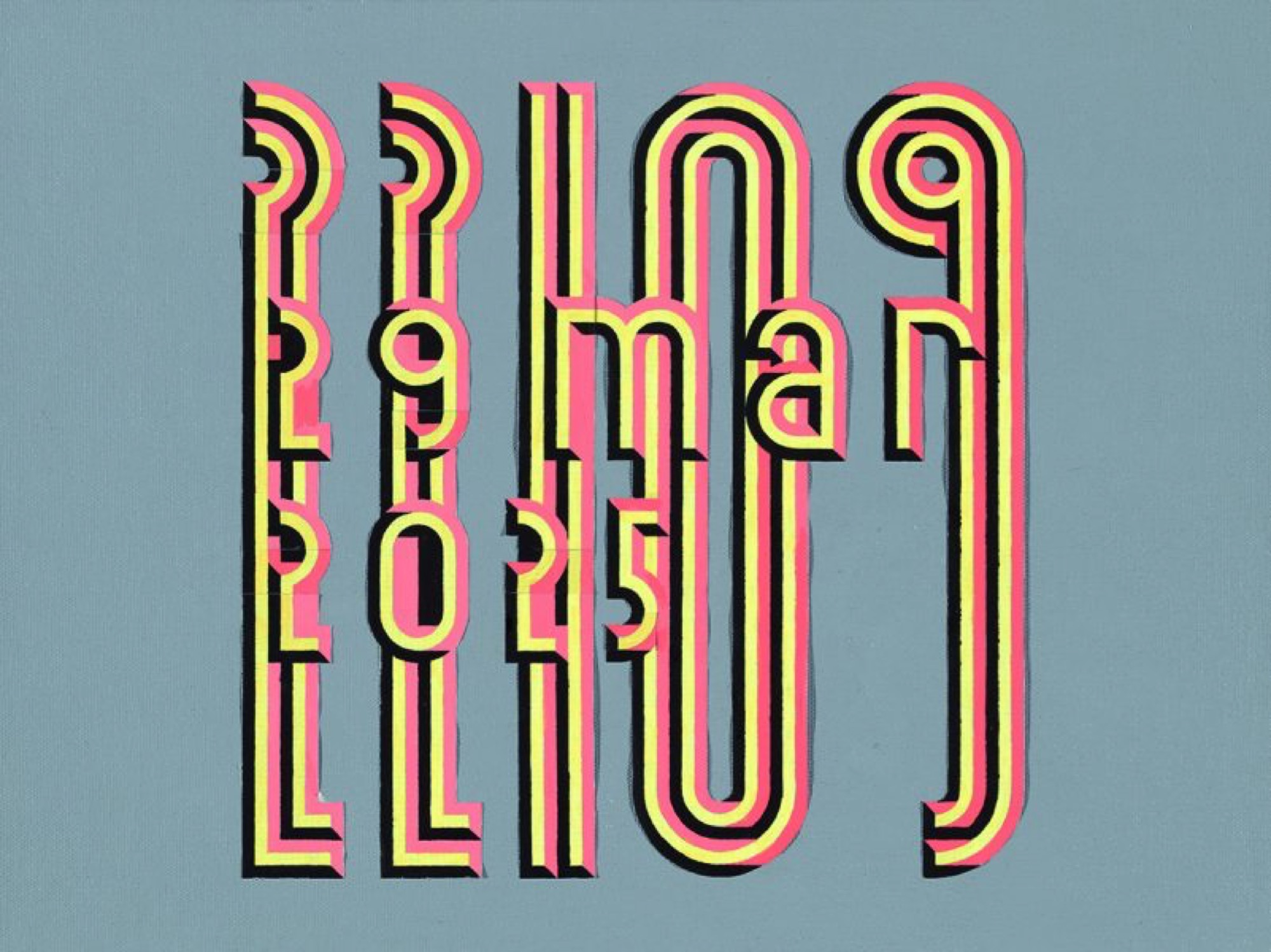

But the real problems of this exhibition are derived from an economy of space. This misfortune forces an uncomfortable hang at times in the show, and at places the walls took on more works than their sentiments could handle. For instance the impact of Çerkez's iconic series of paintings that feature text derived from a telephone dating service was lost to the competition in a room that included some 22 other works. Perhaps suggesting that the pun on romantic dating and chronological dates was either lost to the task or left to be found by the viewer, neither is clear. Where the rest of the exhibition feels paced and complementary, this large room, which makes up almost half of MUMA's total floor plan, lacks division and clarity between works, ultimately informing the misfortunate read of a dealer's stockroom.

The accomplishment of this exhibition lies in its response to a task that was mandated by the work itself. It's disappointing that other recent surveys have not been executed with such delicacy and attention to verve. For example, Jenny Watson: The Fabric of Fantasy, a conceited and over-designed survey exhibition conceived by the Museum of Contemporary Art (and toured to Heide Museum of Modern Art), which one can only feel did a disservice to the import that Jenny Watson's work holds for many of us. Despite the trends in Australian museums at the present, it is a relief that in this exhibition the curators appear to remain mostly absent, giving the work the matter of respect it deserves.

***

Viewing these works in 2018, there is a sense that, before Mutlu Çerkez had even begun the course of his work, there was a foreclosure perhaps necessary for the artist. Aesthetic possibility was abated by a stringency that was commanded by the artist's overarching system. Yet Çerkez was well aware that making art systematically was a pedant ass's bureaucracy, taking its own rule of mastery from the senseless—”It is a system where I can consciously fool myself”. It all carries a futility that is ultimately mistrusted, an anxiety in making and judging art that was perhaps the hallmark of a generation that saw modernity come to a close. The opportunity to reconsider multiple works by this artist together makes it clear that there was something at stake within these margins much larger and more evasive than can be adequately put to words. In the end, what we can be sure of in Çerkez's art is that in foreseeing his own epitaph, Mutlu Çerkez worked accordingly.

Nicholas Tammens is a freelance curator, writer, and childhood educator based in Naarm (Melbourne). At Yale Union this April, he is the curator of one of the final exhibitions by Jef Geys, who passed away in February. He curates 1856, a program sited at the Victorian Trades Hall.

Title image: Mutlu Çerkez, Untitled: 18 April 2013 2002, oil on canvas, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Contemporary Collection Benefactors 2003.)