Installation view of Jelena Telecki, Mothers, Fathers, 2024, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Photo: Felicity Jenkins.

Mothers, Fathers

Toyah Webb

In Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), Sigmund Freud describes a game played by his eighteen-month-old grandson Ernst. The toddler would repeatedly throw objects from his cot while making an “o-o-o” sound, which Freud and Ernst’s mother Sophie interpreted as the German word fort (“go, gone, away”). One day, Freud found Ernst playing with a wooden reel with a length of string tied around it, which the toddler would throw over the edge of his cot (fort), then reel back by its string, exclaiming da! Freud interprets this game of fort–da in two ways: in the first, the game restages the disappearance and reappearance of the mother with objects, thus affording the child control over her absence (she will return); in the second, the child satisfies a repressed impulse to “revenge himself on his mother for going away from him.” For Freud, Ernst’s fort–da is a working through of ambivalence—the unconscious knowledge that the things, or people, we love most are the cause of our greatest psychic suffering. In infancy, it slowly dawns on us that the mother’s breast or bottle (and by extension, the mother or guardian) is an external “other”: a gulf opens, between pleasure and fear of abandonment. There, gone, there, gone again. This vulnerability never goes away. Haunting our mutually dependent relationships, it is what binds us to one another—in love, in pain, in “angst and rebellion.” This, in Freud’s terms, is the central crisis of inheritance.

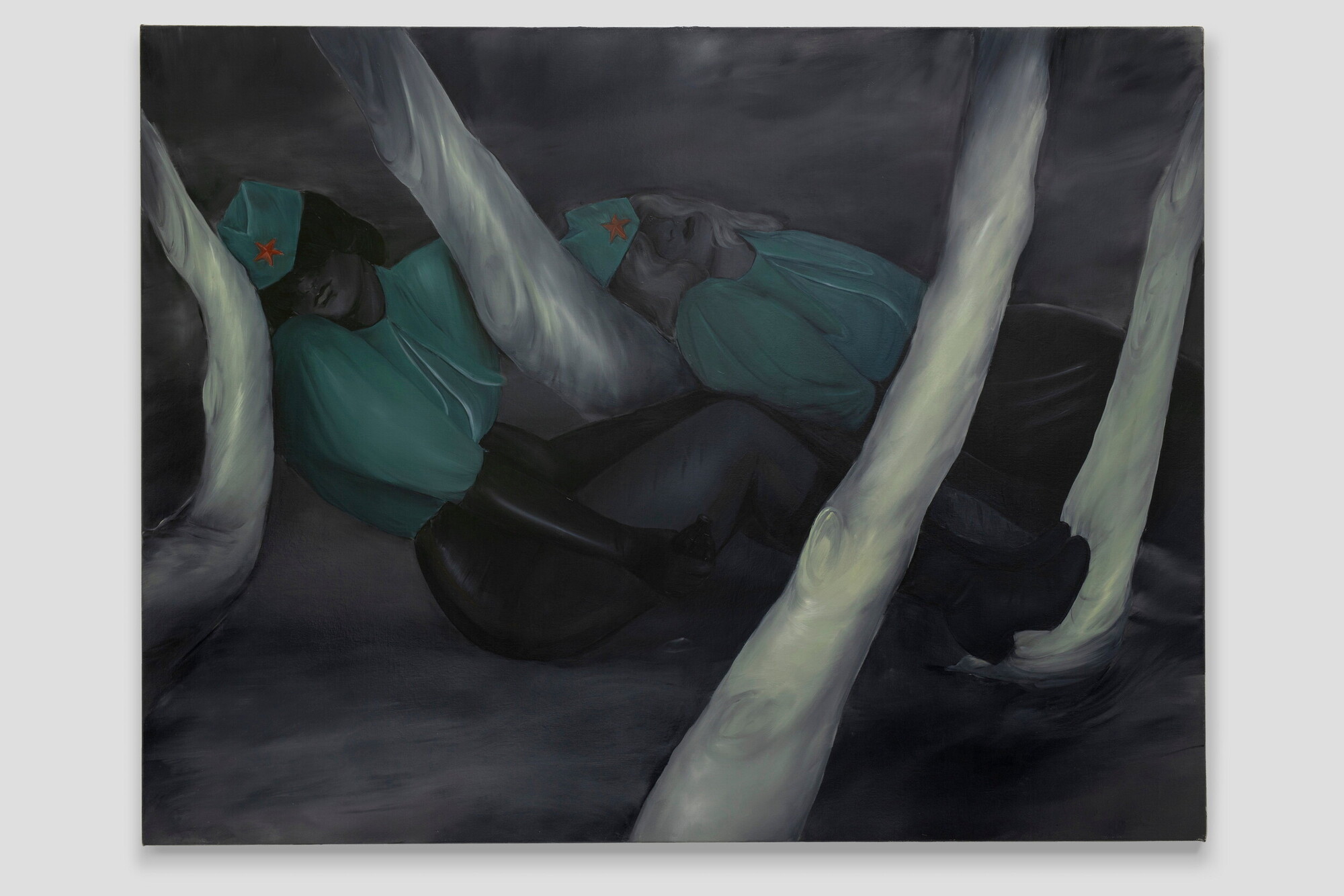

Jelena Telecki, Partizanke, 2023, oil on canvas, 146 x 190 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Courtesy of the artist © Jelena Telecki and 1301SW, Melbourne. Photo: Jessica Maurer.

Jelena Telecki’s show Mothers, Fathers depicts these overlapping “crises.” There are latex-clad breasts, unborn babies, spectral fathers, and Yugoslav Partisans that gesture to Telecki’s Balkan heritage. Pulsing with a phantasmal excess, the paintings (a series developed for the Art Gallery of New South Wales) speak to the psychic traces we inherit from those who come before us, but also the ways we pass these traces to those who come after us: we are complicit in history’s repetitions. In Partizanke (2023), two members of the anti-fascist Partisans—who resisted the occupation of the Axis forces in World War II Yugoslavia—rest in a forest. The ground is obscured by a dark cloud, while pale trees rise from the earth like bones. Despite the looming violence, Telecki’s figures are captured in a moment of tenderness. I am struck by the feet of the Partisan on the left, which rest at the base of a tree. The pose allows this Partisan to keep their knees raised, and thus create a bed for their comrade: the former’s body is angled awkwardly to allow the latter to sleep. However, after Josip Broz Tito’s death in 1980, the diplomatic relations between Yugoslavia’s six republics soured. This was followed by a decade of violent ethnic conflicts in the region, culminating in the 1995 Srebrenica massacre. Against this temporal palimpsest, Partizanke imagines what care might look like on a historical bed of bones. By invoking historical solidarity, Telecki reminds the viewer that grief, like inheritance, is shared. As Judith Butler writes in Precarious Life, grief makes manifest the relational ties (the spectral thread of fort–da) that are fundamental for a sense of ethical responsibility and collective solidarity. Grief, they write, reveals the “thrall in which our relations with others hold us.”

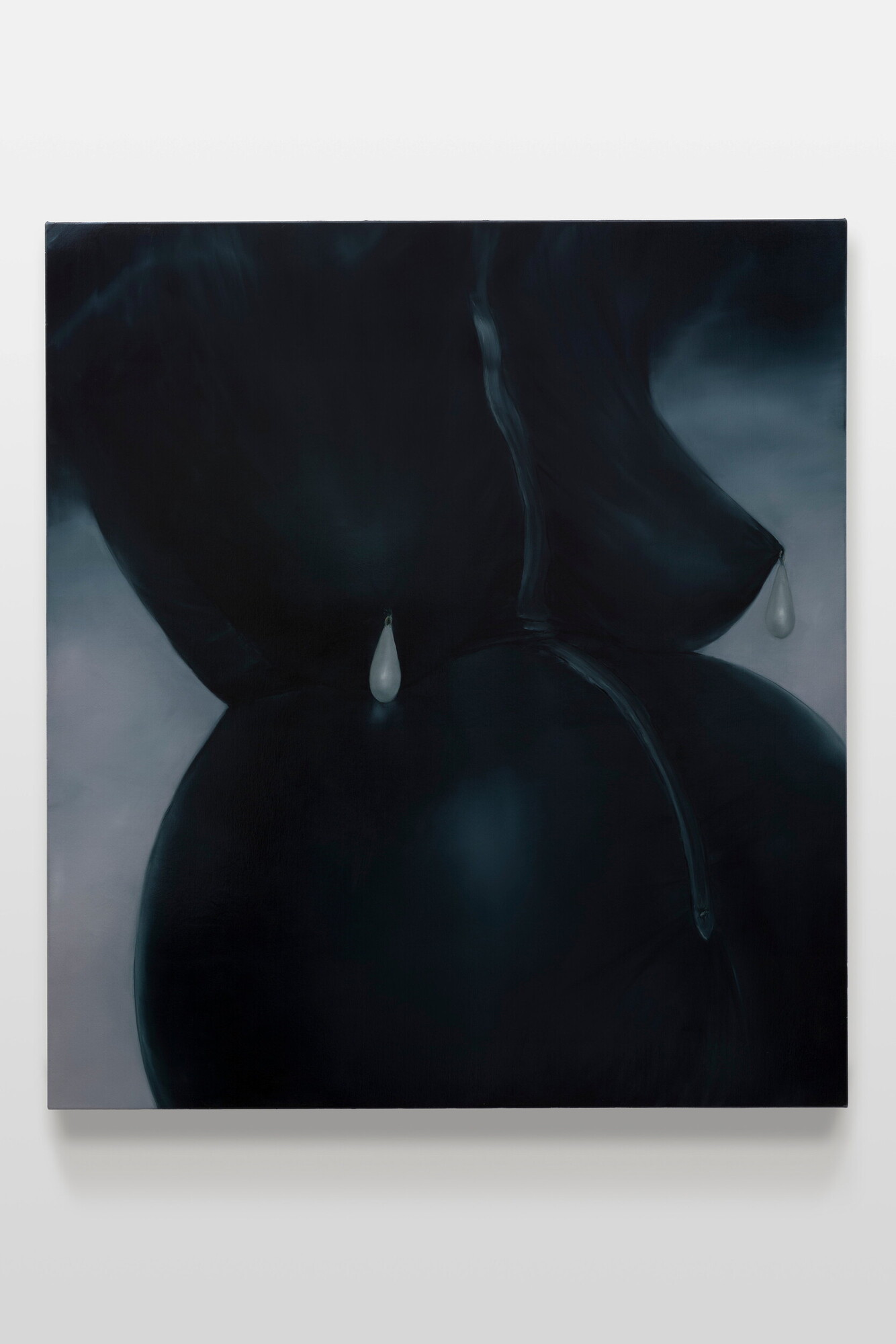

Jelena Telecki, Majka, 2023, oil on canvas, 153 x 138 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Courtesy of the artist © Jelena Telecki and 1301SW, Melbourne. Photo: Jessica Maurer.

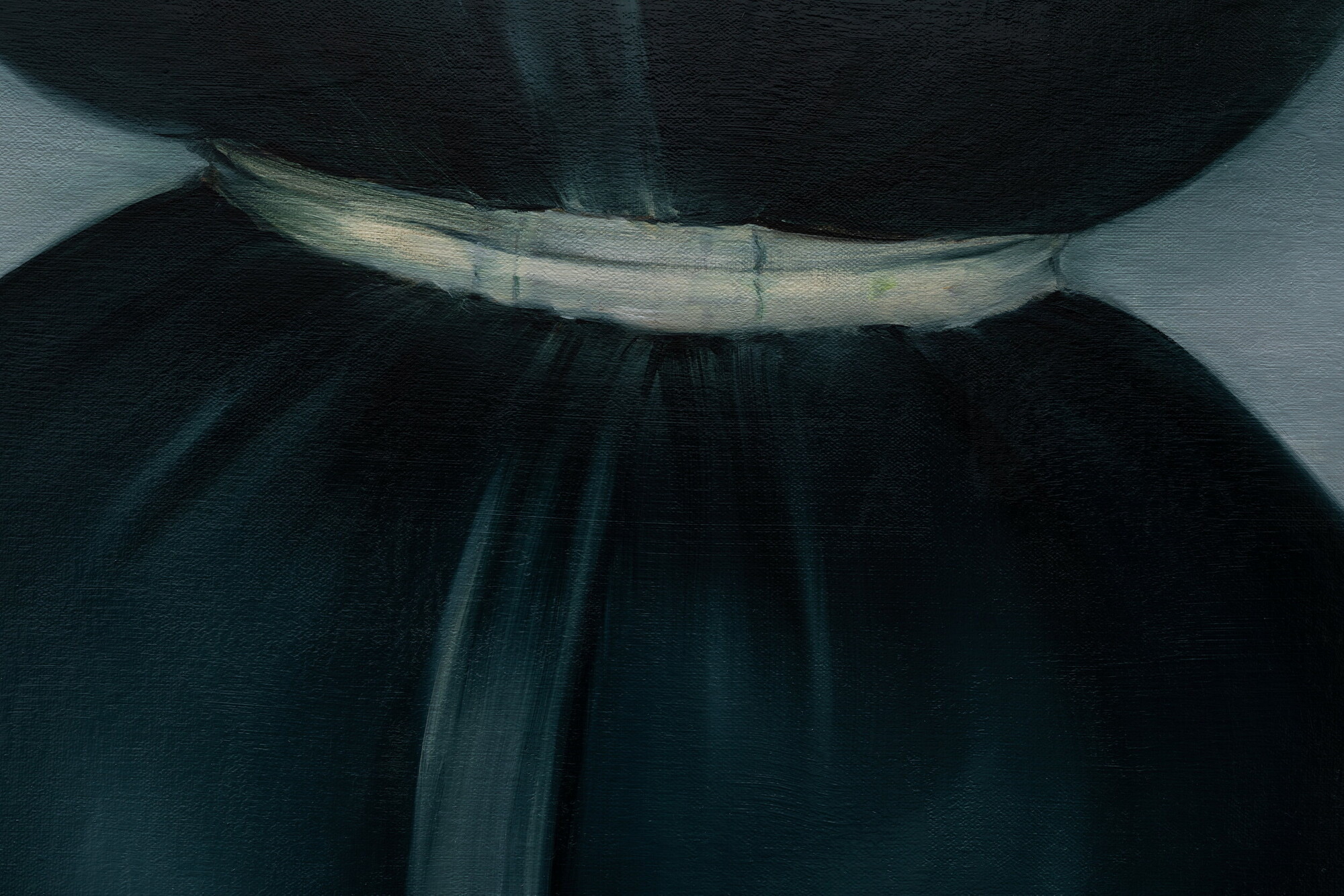

Hanging on the back wall of the gallery, Majka (2023) depicts a feminine torso clothed in a latex gimp suit. Worn by several of the figures in Telecki’s paintings, these second skins are a playful nod to the subtle fluctuations in submission and dominance required for the reproduction of life. In Expecting Couple (2024), a headless duo—fully-clad in “him and hers” gimp suits—pose for a family photo, reminiscent of those staged against artificial backdrops of ocean sunsets or autumnal vistas. In Inheritance (2023), a second feminine torso in a gimp suit is constricted by a white tie at their waist. It is striking that none of these figures have faces. Instead, Telecki strips them of their particular subjectivities and cheekily re-clothes them (suits them?) in universal approximations of their gender-inflected roles.

In Majka, the breast returns as an ambivalent object of nourishment and fear—of love made murky by the possibility of loss (our first trauma). With artistic alchemy, Telecki transmutes mother’s milk into two teardrop pearls, which hang from gold hooks affixed to the nipple of each gimpified breast. In Studies of Hysteria (1895), Freud and his colleague Josef Breuer characterise psychic trauma as a “foreign body” that continues to work long after it has entered one’s body. Eventually the trauma is displaced and reproduced as a symptom. In a later lecture, Freud compares this process to an oyster creating a pearl (an oyster defends itself from “foreign bodies” by encasing any irritants that enter its shell in nacre, otherwise known as “mother of pearl”). Telecki’s overdetermined accessories make me wonder whether mothering is a type of pearl making. Or is it the infant, lips dripping with a milky “foreign body,” who develops an opalescent case? Who is protecting whom?

Detail of Jelena Telecki, Inheritance, 2023, oil on canvas, 90 x 66 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Courtesy of the artist © Jelena Telecki and 1301SW, Melbourne. Photo: Jessica Maurer.

But, Dear Reader, this is where things get really spooky. While writing this review, Microsoft Word glitches. First the screen freezes, then, after a brief intermission, goes completely black. I am about to close my laptop when fragments of text begin to flash up on the screen, and the ghost in the machine (a writerly poltergeist?) takes over. The first fragment reads: “ps / is the first crisis of inheritance.” Then: “Ernst play / throw over / game of / the mother.” Fragments repeat, appear, then disappear again in a game of digital fort–da. This continues for a few minutes, before concluding with the lyric apostrophe, “I / Jelena Telecki.” This final expression—an articulation of ghostly identity, formed with the emphatic “I” of the italicised shortcut at the top of the page—evokes the conventions of demonic possession or a séance. The “I” is transformed into an other, or an “I” that cannot be trusted.

In demonic possession or a body-haunting, the possessed subject speaks “I” with a voice that is eerily theirs and not-theirs; a false articulation ruptures the stable relation between “I” and the proper name. But this is also the wager of psychoanalysis: no matter how well we think we know ourselves, there is always a part of our “I” that remains unknowable. We are haunted by the dark twin of our “I”—the unconscious that floats below the surface of knowing, a nocturnal sea of ghosts. Inside the latex-sealed urn of Vessel (2024), I imagine that there lurks another urn, then another, and another, in an infinite series of matryoshka dolls (a spool of little mothers).

Installation view of Jelena Telecki, Mothers, Fathers, 2024, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Photo: Felicity Jenkins.

Near the entrance of the room at AGNSW, a small painting depicts two hands holding an X-ray of a femur and tibia. The image emits an otherworldly light, glowing against a curtained backdrop that evokes a hospital, morgue, or photographer’s darkroom. Mum’s Knee (2023), I later learn from the curator, is a painting of a photo taken by Jelecki’s son, of his aunt—the artist’s sister—holding an X-ray of their mother’s knee. This cast of characters is disorienting; the viewer must work their way through artist/mother/daughter, son/nephew, grandson, sister/aunt/daughter, before arriving at the subject of the painting: mother/grandmother’s knee. Tethering her family to the maternal signifier, Telecki’s painterly remediation reverses the game of inheritance. Instead of holding the child, like the mother in Expecting Couple, the child holds the “mother,” who is in turn held by our interpellated gaze. I look for the break suggested by the X-ray and realise that perhaps the mother’s body—tessellated across the room in metonymic fragments and repetitions—is the break, a phantasmic abîme that offers an alternative to the chain of inheritance determined by paternity, proper names, and historical forefathers. Yet Telecki’s “game of mother” is also a game of the mother, and she can choose whether to pick up the toys or not: throw over.

Toyah is a writer and PhD candidate living on Gadigal land.