In the notes published for his 1994 ACCA exhibition, Thesis, John Nixon writes the following:

The “Exhibition” is provisional by nature…The art of exhibition is a dialectical relationship between painting/object and the room (gallery, warehouse, museum, etc.) which the given orthodoxies about hanging and placement are questioned…The exhibition here is not merely “the frame” for the works but an active/ (provisional) arrangement of its parts, integral to the art.

This thesis gives atmosphere to Conners Conners current side-by-side exhibition, a double-chambered display featuring Isabella Darcy’s Articles of Blue, Black and White and the late John Nixon’s Monochrome/Piano 1992.

For the last three years, Conners has occupied two rooms of the Fitzroy Town Hall situated in the middle of Napier Street. Built in 1873, its Victorian-era grandeur has been re-fitted by artists and co-curators Ry Haskings, Vince Alessi and Narelle Desmond to house an intimate, white-cube, artist run gallery. Indeed, as a dual functioning site, caught between civic duty and aesthetic commitment, Conners embodies the dialectical entwinements Nixon noticed in the “provisional exhibition” nearly three decades ago.

It is therefore rather apt that Conners, working closely with the Nixon estate, has had the opportunity to restage this installation for its third public display, the first instance being at Seoul’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 1992 and the second at his previously mentioned ACCA show, Thesis, in 1994. Split across the two front rooms of the town hall, the ensemble exhibition brings into dialogue the practices of Darcy and Nixon, intergenerational artists and friends, whose relationship through art is shadowed by the architectural history of this gallery space, in which the imbrication of art with life is never far from one’s mind.

A rigorous and prolific analysis of the correspondence between “painting / object / room” was, of course, an ongoing project developed throughout the entirety of Nixon’s vast oeuvre. Indeed, the depth of this investigation could be traced across several of his recent solo exhibitions held in the preceding months across Australia, notably Guzzler’s John Nixon, Anna Schwartz’s White Paintings, Sarah Cottier’s Single Object Paintings and the Canberra Museum & Art Gallery’s Life as Art. While each of these present an impressive selection of Nixon’s work, with a varied emphasis on his geometric abstractions and monochromes, Conners’ restaging of Monochrome/Piano 1992 brings a particularly focused attention to a problematic which animated Nixon’s practice during a key period of his career.

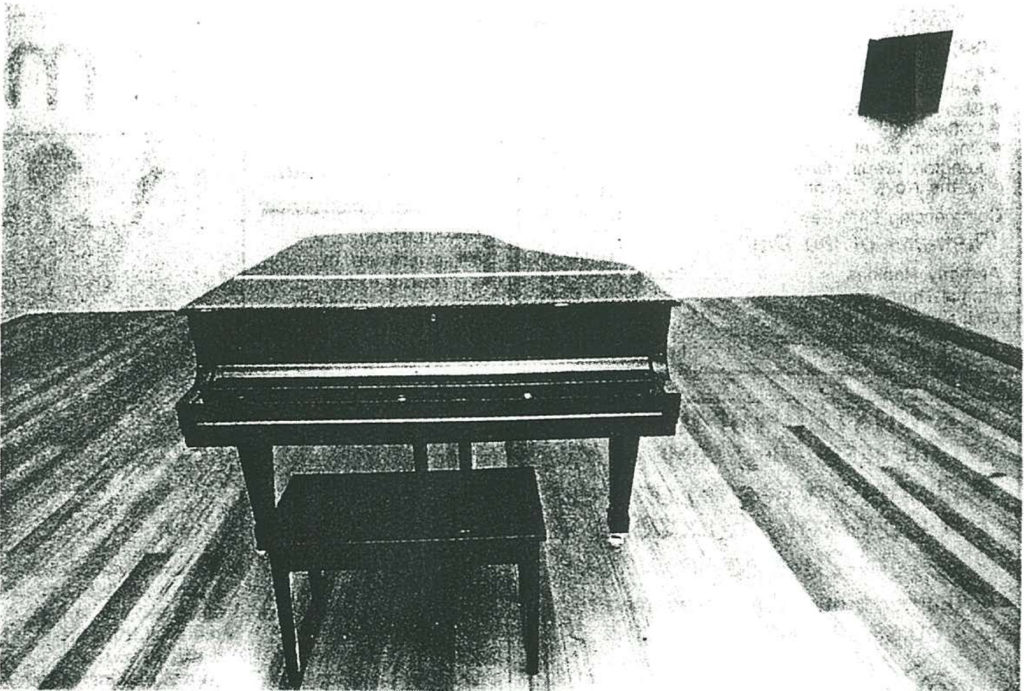

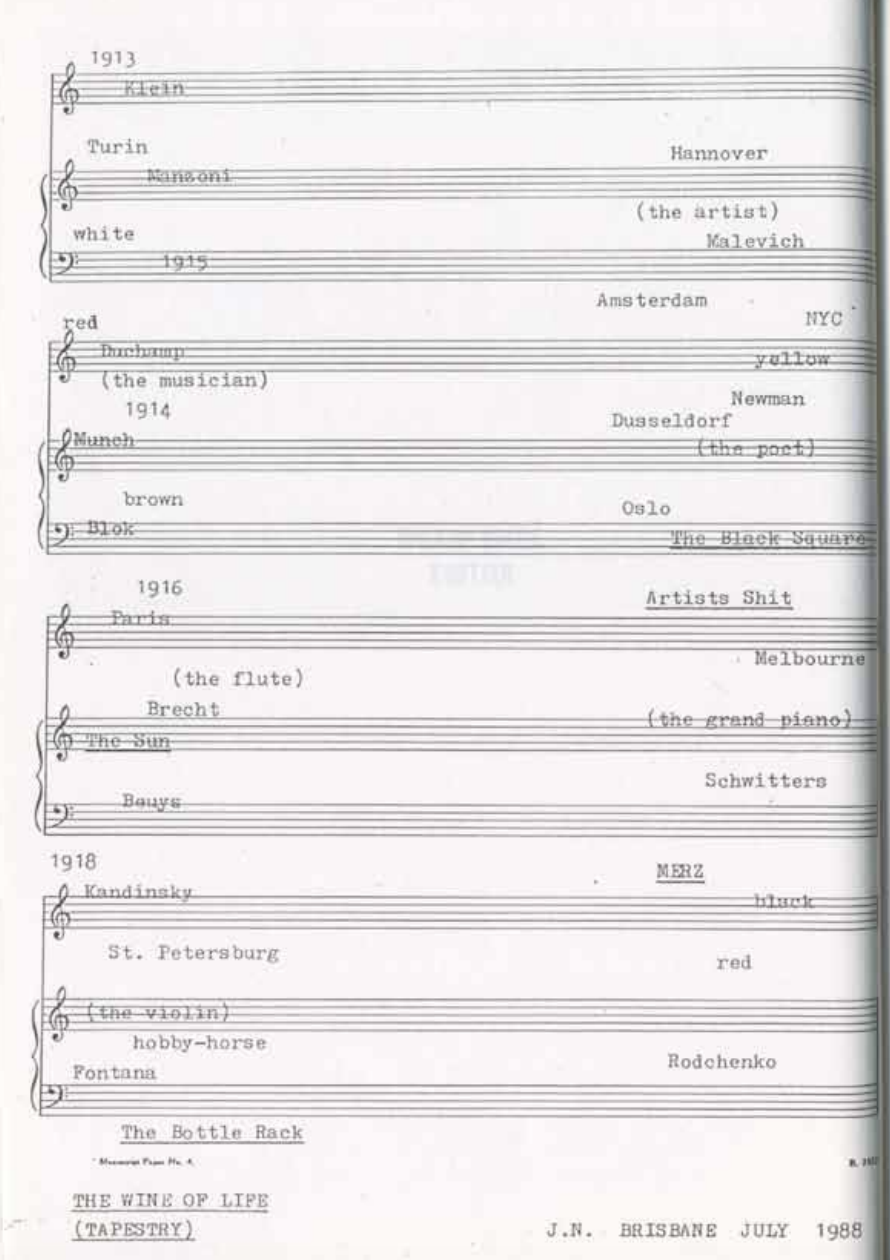

Entering the room, I am met with a flush of colour. The gallery walls have been painted over with a brilliant cadmium yellow that matches the accompanying room sheet, a reproduction of an original score annotated by Nixon in 1988, The Wine of Life (Tapestry). In the centre of the room sits a grand piano, its lid unpropped and keys covered. The instrument appears as one solid mass of glossy black, accented with brass fittings. This is reiterated by the single black monochrome painting hung in the corner of the room, whose hessian surface offsets the glint of enamel paint while maintaining its reflective instinct. Wedged between the “yellow-cube”, the painting purposefully blunts the sharp right-angle of the gallery walls. It hangs well above eye-height, which actively dwarfs the room as it draws my attention to the top of the gallery wall. Looking back to the piano that dominates much of the floor space, the shrinking effect is amplified.

Nixon’s formal manipulations revest the materiality of the gallery itself. The wall studs left visible to anchor the gallery atop the civic-stained carpet; the town hall’s original egg-shell walls and revival arche windows peaking over the top of Conners’ façade. Much like the piano or any readymade art object, the town hall is an exemplary instance of the “banal”, a zone of municipal bureaucratese, an archive of quotidian history. Nixon’s exhibition draws this situational content into relief without enveloping it entirely. While the installation harnesses its situational context, the town hall remains discrete—a reminder that the readymade as art object maintains an everyday function to which it can return. As Nixon puts it, “a suitcase which is in one exhibition can be taken on the flight to Los Angeles, as a suitcase again. Its function is not lost”. The gallery walls now double as both monochrome and readymade within the confines of Fitzroy’s Town Hall, fluctuating between the categories of painting, object and room.

On his choice of the piano-as-readymade, Nixon has previously described the musical instrument (much like, say, a mallet or handsaw) as a tool of its discipline. That is, the sensuous objecthood of the grand piano—its luxe satin surface, the roundness of its body, the dimpled curve in its side—directly informs its purpose and the potential sounds it can produce. By adopting the piano into his artistic practice, Nixon reinscribes the instrument with the popular maxim, “form follows function”, paradoxically emphasising the functionality of the object directly through its formal properties. This antimony seems to reverberate up the gap between the doubled-up interior walls, whirring between function and aesthetic, civic and artistic, eggshell and cadmium.

As I walk around the piano, shifting reflections bounce off its glassy exterior. The brass hardware turns to gold from the all-encompassing yellow atmosphere…Lane Cormick—local artist and city-dweller tasked with the job of painting the install—must have the Midas touch. Standing in the corner of the room opposite the hessian monochrome, the hinge along the piano’s spine cuts through its reflection, splicing it in two. The combination of the two black reflective surfaces under the LED light exacts a sort of double negative, bringing a whiteness into the canvas that causes a sort of gradient effect on the otherwise opaque monochrome plane. This intensifies the texture of the hessian surface, with tufts of fibre transforming into a landscape whose peaks and dips are illuminated by the sharp gallery light. That Nixon’s intention for this installation was to elucidate “the relationship between the monochrome and the readymade” is made concrete by the image of their surface and reflections coalescing, forever in flux.

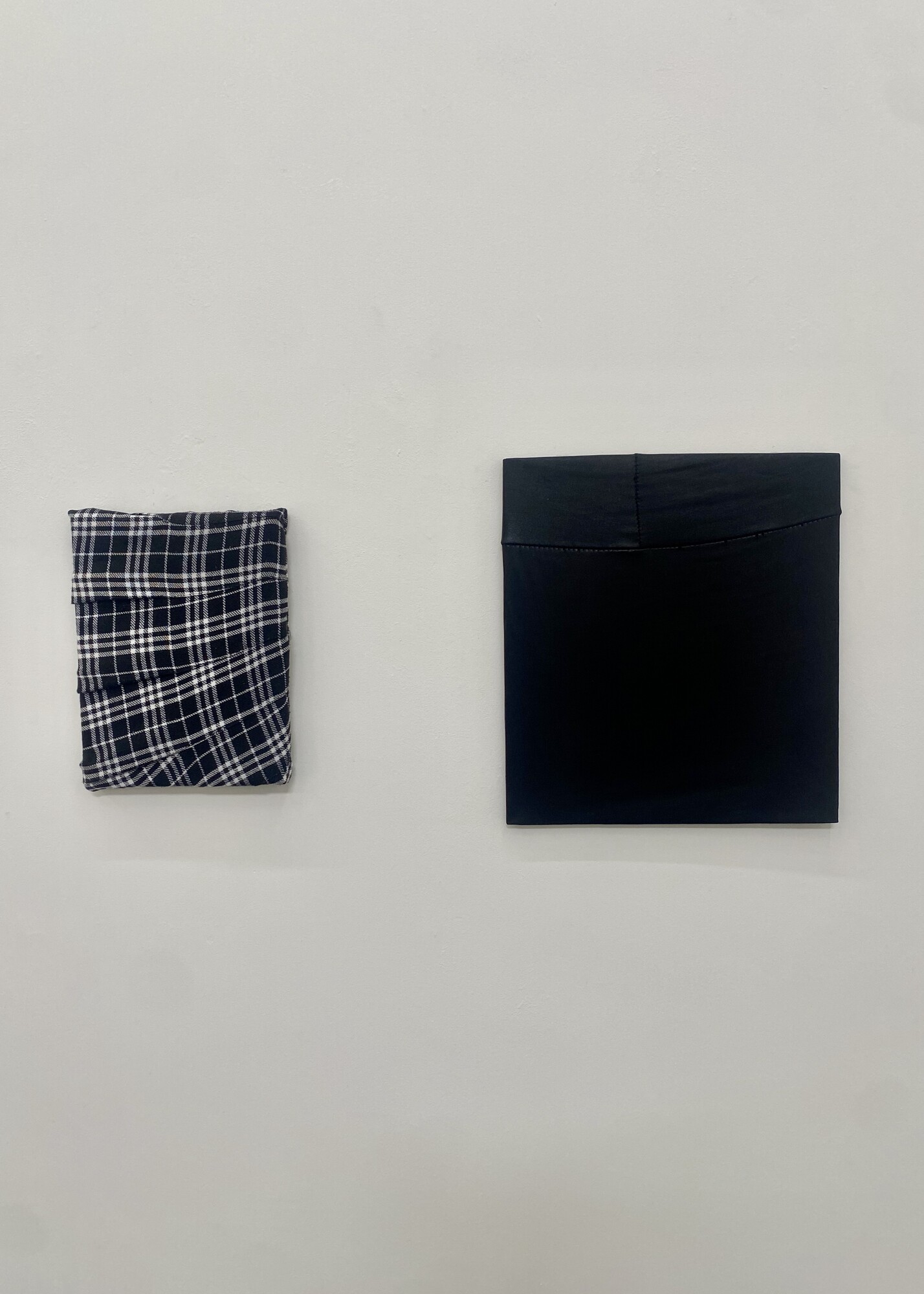

Walking back into Gallery One, I am reinitiated back into the white cube. Here I’m welcomed by eleven of Darcy’s fabric stretched canvases and one framed cyanotype print. Couplets of variously sized canvases donning found and reclaimed fabrics—towels, cottons, denims—line the gallery walls at eye-level. I am drawn to the duo, Untitled (black and white tartan wrap) (2022) and pleather pull (2019). To the left is a small canvas dressed in what looks like a pleated tartan mini skirt, and on its right is a slightly larger surface stretched with pleather leggings. It’s a chic outfit, really. What attracts me to the set is how the otherwise straight linework on either fabric, be it the stitching or pattern, has become manipulated by Darcy’s stretching. The tartan skirt bends vertically to the right as the pleats unfurl. And the leggings’ seam, running horizontal along the canvas, bows downward like it would over a rounded stomach. With a deliberate faux touch (its pleather, after all), the work echoes the curve of Nixon’s polished grand piano, whose stiffened hinge then rebounds back to the perpendicular seams on Darcy’s respective denim works, Untitled (stitch) and Untitled (fade), hanging on the other wall.

Articles of Blue, Black and White feels very much like an extension of Darcy’s ongoing artistic project. Speaking with her, she explains how the print works, Moodboard #29 (cyanotype) (2022) and prototype (2020) braid into her ongoing project Reworked—an investigation into material process and production of consuming and wearing via photographic and archival studies. These are in correspondence with her textile works, works she describes as “archetypal vignettes”, informing the materials and colours archivally selected to dress her canvases. I am struck, however, by how the show seems to work in dialogue with Nixon’s installation. Aside from the clear link to be made between the artists’ utilisation of non-art materials, there is a deeply intuitive exchange registered on the fundamental level of form and colour that becomes equally apparent.

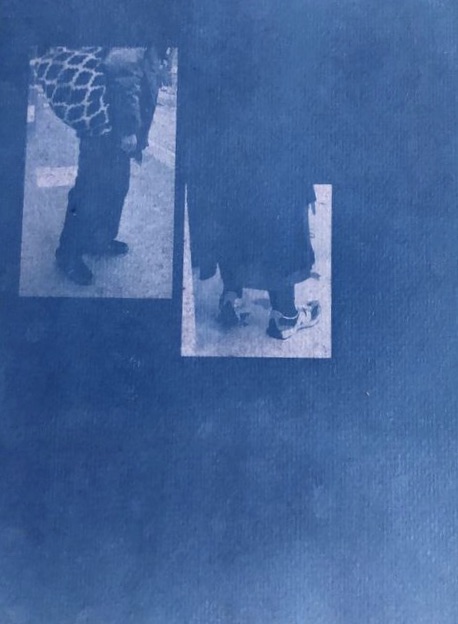

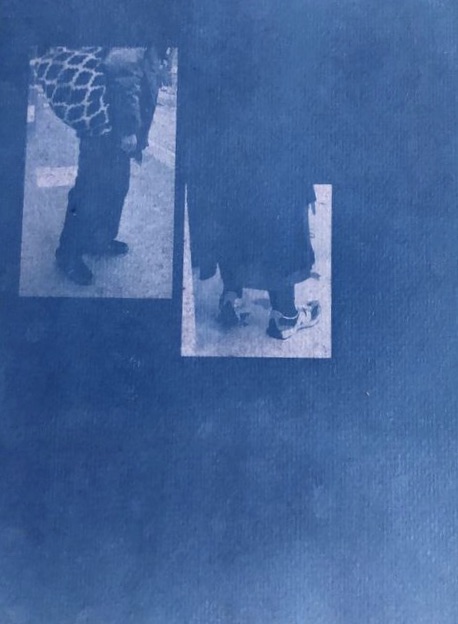

Take the cyanotype print, Moodboard #29 (cyanotype) (2022). Pictured on the washed blue sheet of paper are two separately cropped images positioned in the centre and upper-left quarter of the frame. They each depict a well-dressed body standing in the street from the waist down, compositionally standing kind of “together separately” in a field of blue. Similar images were used in Darcy’s show last year at Haydens Gallery, Reworked: Moodboards and Assembled Behaviours, and her paste-up show On the Path, co-curated by Babs Rapeport. However, the flush of Prussian blue effected by the cyanotype printing process—a photochemical method that produces monochromatic blue images by exposing chemically doused paper to UV light—recalls the twentieth century monochrome tradition whose inheritance is so clear in Nixon’s work.

Darcy’s quiet nod to her long-term mentor—to the memories of friendship that reside in the contours of developing form—is poignant but it doesn’t dominate the uniqueness of her developing practice. The ethereal quality of the tonal Prussian blue harmonises with the otherwise everydayness of Darcy’s archival studies which seek to investigate value production, commodity objects and design. It sings to me David Berman’s lyrics, that “all houses dream in blueprints”…words that immediately pull me back into the building I stand in. First to the town hall, then to Conners.

Camille Orel is a writer living in Naarm/Melbourne.