Monet & Friends

Luke Smythe

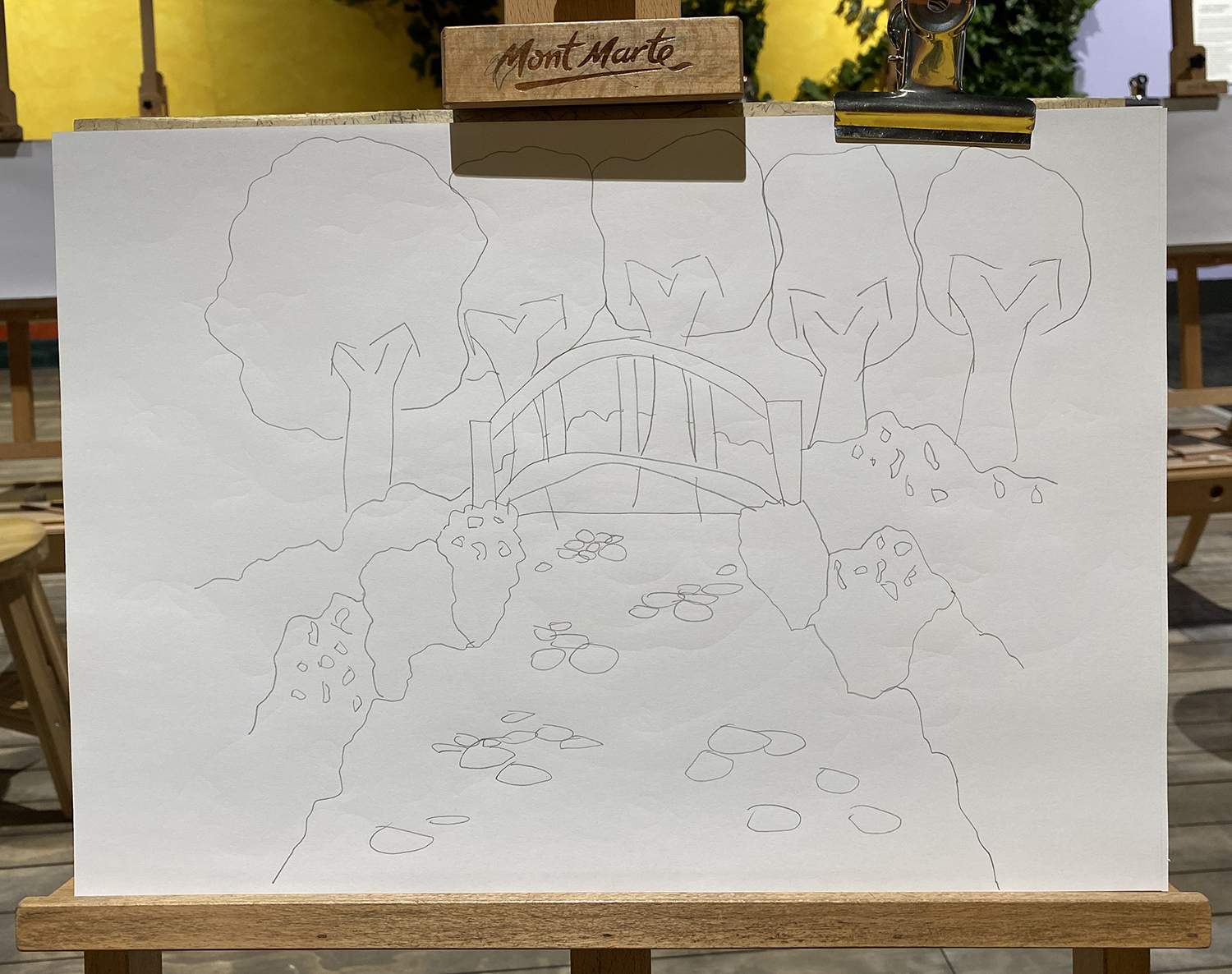

Since its Covid-delayed opening last year, digital exhibition space The Lume has welcomed more than 700,000 visitors. Its inaugural offering, Van Gogh (known also as Van Gogh Alive), tapped into the endless public appetite for all things colourful, creative, and out of copyright from late nineteenth-century France. This year’s sequel, Monet & Friends, offers more of the same fare, plunging viewers into a forty-minute animated mélange of work by Monet and a dozen related artists, synced up to a mega-mix of classical music favourites from the period. It is, however, no mere AV light show, for it is also suffused by its own scent, intended (according to a wall text) to transport visitors “to the lush gardens, mountain slopes, and spreading landscapes, where the Impressionists painted their timeless masterpieces.” Add to this peripheral attractions, like a life-size simulacrum of Monet’s footbridge at Giverny, an art studio with a video tutorial, in which one can draw the footbridge for oneself, and a simulated Paris café, from which one can view the action en terrasse, and it is evident that Monet & Friends owes as much to theme parks and Las Vegas as it does to more venerable institutions like the Gesamtkunstwerk, with which its source material was contemporary. While its pedigree is evident, its purpose is more difficult to fathom, in large part because its organisers appear to be unsure of their own goals and may indeed have chosen the wrong medium with which to pursue them.

To begin with, their selection of artists conflicts with their stated ambition (announced on The Lume’s website and elsewhere) to take visitors “on a spellbinding journey through the vibrant world of French Impressionism.” A journey roughly along these lines does indeed take place but surprising stops are added along the way. Monet appears, as expected, and so do his Impressionist contemporaries (Pissarro, Renoir, and the like). But what are we to make of the inclusion of Pointillists like Seurat and Signac, who ranged themselves in opposition to Impressionist spontaneity; of figures with connections to Realism, like Degas and Manet; of the Nabi Bonnard’s brief appearance; and of the segments of the mélange devoted to Cézanne and Toulouse-Lautrec (the latter synced-up to what else but the can-can)? The show’s commitment to art history is so slight that it remains content to lump all of these artists beneath that most marketable of monikers, Impressionism, whose key features and achievements it does convey fairly clearly to a “general” audience but whose links to other movements and artistic developments it makes no effort to explain.

Monet & Friends’ art-historical component consists mainly of brief quotes from the artists and concise, informational statements, inserted between its numerous short sequences of imagery. From the statements we learn that the Impressionists preferred to work outdoors, and that unlike prior artists they chose to depict “ordinary” people going about their business in the present, instead of grander scenes from myth and history. The en plein air claim is, of course, a solid one, but for the benefit of those unfamiliar with the art of the period, why have we been offered no examples of the kind of work against which the Impressionists reacted? And what exactly do the organisers mean by “ordinary” people? I suspect they are referring to the Parisian bourgeoisie; but, if so, should we not spare a thought for the peasants and the burghers of the Low Countries on which genre painting had been focusing for centuries? Here too some contextualisation would have been enlightening.

The artists’ quotes included are a mixed bag and are as likely to confound as to illuminate. Degas protests at one point, for example, that nothing could be less spontaneous than his painting methods, a claim that those familiar with his work will know to be correct. But how are we to square it with the show’s insistence elsewhere that Impressionists audaciously improvised in a bid to capture transient phenomena? Does this technical discrepancy imply that Degas was no Impressionist, as he himself and many critics and historians have maintained? Or is he just a complicated case whose work obliges us rethink what the movement was about? A side gallery with bios of a number—but for some reason not all—of the artists promises to shed light on this issue. Instead of helping readers weigh the merits of the two competing claims, it simply notes the artist’s preference for the label “Realist.” That this claim might have its merits is nowhere entertained, nor is it ever noted that Realism was itself an art movement. Since readers unaware of this fact will likely equate “Realist” with “realistic”—a term applying equally to Impressionism—it is hard to see the value of this omission.

Other artist bios generate confusions of their own. The text on Lautrec, for instance, begins by telling us that “Modern physicians attribute Lautrec’s disability to a genetic disorder, caused by his aristocratic family’s history of inbreeding.” The nature of this malady, however, and how it might pertain to his work, remain unspecified. Perusing the show’s program in the gift shop will help resolve the first of these enigmas by revealing, in the opening sentence of a somewhat longer version of the bio, that said disorder gave him problems with his legs. But how this might have influenced his work is not disclosed, and the excision of that sentence in the gallery is puzzling to say the least. Perhaps the edit happened in a hurry, or the organisers felt that no-one would be paying much attention to the bios anyway.

People do, of course, attend to the projection itself, which is, if nothing else, technologically impressive. Throughout the presentation, elements of each painter’s work come and go from the zig-zagging walls of the exhibition space: an enormous trade fair hangar, into which towers of stacked cubes and a cylindrical side room have been plonked arbitrarily, presumably to add visual interest. On occasion, complete paintings appear, but for the most part the organisers have taken a free hand with the material: lifting details from it, animating them selectively, repeating and juxtaposing them with chunks of other works, and so forth. Despite these rather rude interventions, they survive the jump in scale from the easel to the wall impressively, a testament not only to the artists but also to The Lume’s projection prowess, which only falls short during sequences that zoom in on a single colour—all of which look fuzzy and washed-out.

Alas The Lume’s lack of interest in art history can make it hard to know what one is looking at. Not only are the works never labelled but when quotes from the artists appear, they often do so in conjunction with another artist’s work. A statement from Cézanne, for example, is juxtaposed with scenes of urban life of a kind far removed from anything he ever undertook, though only those who already know his painting will discern this. To establish who made what, one needs to look elsewhere, and since neither the program nor the wall texts make it easy to identify many of the paintings in the show, one will need to go beyond the information provided by the venue. Last year in The Age, The Lume’s owner and founder, Bruce Peterson, suggested that many people find traditional galleries “sterile,” in part because “they don’t know what they’re looking at.” But how Monet & Friends aims to redress this deficit is unclear.

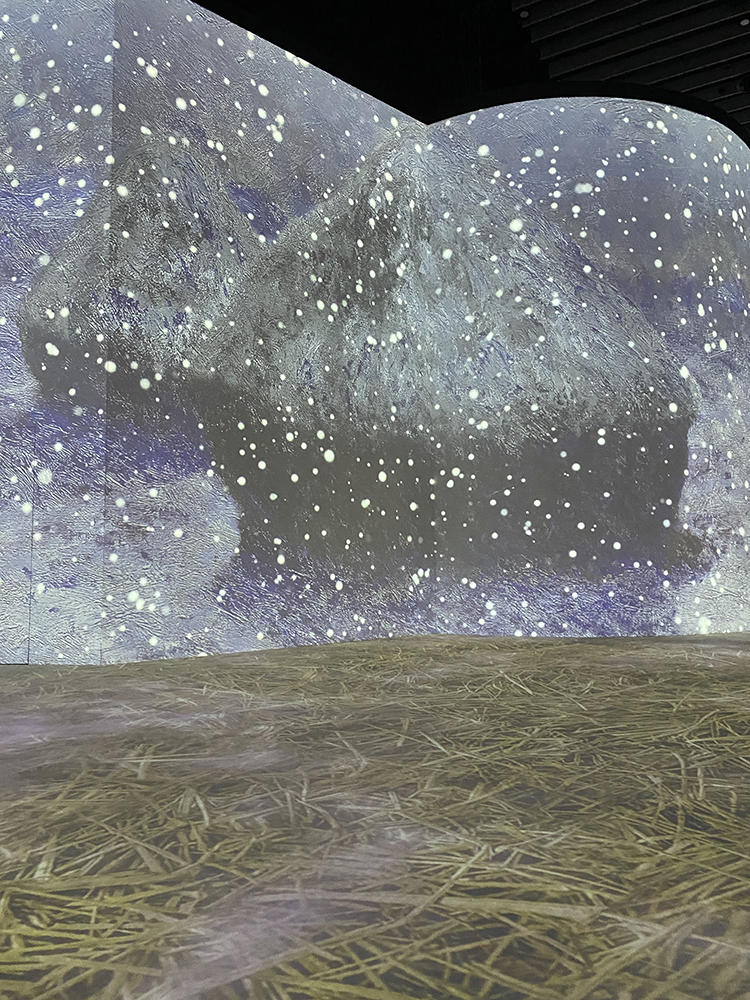

Occasionally, film footage of some of the subjects shown in the paintings is added to the mix, like tulip fields or a puffing locomotive. These segments are presumably intended to help us gauge the skill of the artists in capturing the scenes that they evoked. Whether they are useful to anyone who hasn’t seen such things in real life is unclear, and it’s hard to tell why some subjects and not others were selected for this treatment. Elsewhere, digital additions have been made to some works, like the plethora of drifting, fuzzy dots that descend to veil one of Monet’s haystacks. The dots are presumably intended to register as snowflakes, but like all of The Lume’s animations they are graceless and jarringly out of place. Pervading all of this is the show’s fragrance, which the organisers describe as a “powerful” olfactory addition to the show, “inspired by en plein air painting.” They go on to break it down into “top notes,” “middle notes,” and “base notes,” which together are supposed to smell outdoorsy. Would that it were so, but my own sense of smell is either too coarsely indiscriminate, or the fragrance itself is too sickly, to credibly convey the “fresh floral, citrusy, and woody fragrances” it seeks to simulate. Far from being transported to a meadow or a forest, I felt at times like I was sniffing out a purchase at a shisha shop, standing near a surreptitious vaper, or visiting a damp apartment block, whose musty odour is in need of concealment.

Had the organisers candidly declared that Monet & Friends is simply a diversion, which allows us to happily spend time bathed in colour, light and scent, such historical and sensory faux pas might not have been so galling. For if one passively submits to the spectacle, the experience is frequently delightful—full of mutually enlivening conjunctions of sound and vision, in which the drifting patterning of imagery on every nearby surface transforms an architectural blank canvas into a radiant elsewhere. Yet the organisers stress that mere sensory distraction is not their aim. Instead, they are attempting to bring history to life by plunging viewers into stirring simulacra of the artists’ creative milieux: “Don’t just admire the Impressionists, become part of their movement,” the website trumpets, before inviting us to take an “exhilarating adventure across nineteenth century bohemian Paris and countryside France.” The purpose of this trip, one assumes, is to enhance appreciation of the works that the show has so casually dismembered. But it strikingly fails to deliver on this promise and on its attempts at historical immersion. So art historically inattentive are the organisers that they’re happy to include within their line-up of quotations generic remarks on colour from Expressionist Marc Chagall. So pronounced is their lack of interest in keeping faith with an experience of the paintings that they distort them willy-nilly in pursuit of their own aesthetic goals. To enjoy The Lume’s display is therefore to appreciate an object whose links to the original artworks is tenuous at best.

With more careful calibration of image-text relationships, these problems might have been alleviated. However, it is doubtful that they could have been eradicated due to a deep and perhaps fatal misalignment between painting—which is silent, tangible, and static—and The Lume’s dynamic, AV technology. As a brief presentation of several additional projections (which appear at the end of the main feature) makes evident, native digital material fares better than remediated analogue originals. A striking case in point is Bioluminescence by Andy Thomas, in which fantastic, glowing creatures drift and dart through a liquified and fractalised environment, redolent of deep forests and ocean depths, which have been heavily abstracted. Although only a few minutes in length, Thomas’s fantasia is absorbing. Not only is it usefully unburdened of the main feature’s narrative ambitions, but its auditory component is coupled far more tightly with its visuals. While no doubt far less viable commercially than Monet and his friends, Bioluminescence and the two additional shorts—Ghost Trees by Nature as Data, and Grayson Cooke & Dugal’s Australian Cloud Atlas—feel far more at home on The Lume’s platform. Perhaps we can look forward to an independent program of such material in the future, or at least to a more substantive and ambitious art-historical experience.

Luke Smythe teaches art history and theory at Monash University.