Mitchel Cumming and Kenzee Patterson: A redistribution

Nick Croggon

Weighing down the floor of Verge Gallery at the University of Sydney are two massive stone discs. Pocked and tarnished with age, they crouch low to the ground on unglamorous metal pallets, the sides smooth and the top worked into a system of furrows that move outwards from a hole in the middle.

The stones are, in fact, nineteenth century basalt millstones, and they form the aesthetic and conceptual centrepieces for Mitchel Cumming and Kenzee Patterson’s collaborative exhibition, A redistribution (2023). As the show’s room-sheet explains, the millstones were used between 1812 and 1830 at a flour-mill established by the settler Thomas West on Gadigal Country in the area now known as Paddington, and are currently on loan from Sydney’s Museum of Applied Arts and Science (the Powerhouse).

The millstones entered the Powerhouse’s collection in 1906 and, it seems, have rarely left storage since. This is perhaps unsurprising—they are unbeautiful, unwieldy things. Getting them to Verge was no easy matter. As the exhibition text details, it took a year of careful correspondence and paperwork, and a team of engineers, conservators and administrators to measure and document Verge’s humidity and air quality, dimensions, and weight bearing capacity. It is because of this latter capacity that the two stones (which in use would have been placed one on top of the other) are spaced apart—the show’s first and most obvious act of redistribution.

While the stones are not much to look at in themselves, their redistribution at Verge enacts a kind of clever institutional critique. The seemingly simple journey of the stones from museum storage to gallery floor drew to the surface the usually invisible infrastructure that makes such display possible, and the vast resources dedicated to this infrastructure’s maintenance.

There is, of course, more to it than that. Indeed, a signature of this exhibition is the way it rewards time spent lingering over its works, each layer of meaning requiring time to unfurl. This mode of engagement is encouraged by the inclusion of audio descriptions for some of the works, developed by the artists in collaboration with Sarah Empey, and Sarah Barron. This set of detailed ekphrases provides more than just a base level of accessibility for the blind and low-vision community—they are a crucial access point for grasping the complex processes that the show is concerned with.

A redistribution is just one iteration (perhaps the culmination) of Cumming and Patterson’s years-long engagement with the millstones. One origin-point for this project can be traced to a transformation that took place in Patterson’s sculptural practice between 2017 and 2019. Energised by his graduate study at the University of Sydney, Patterson sought to reorient his art practice away from the mere production of art objects, and towards a more ethical relationship with his surrounding environment and its materials, especially rock.

As Patterson has explained, this reorientation was prompted in large part by the work of Goenpul scholar Aileen Moreton-Robinson. The patriarchal white sovereignty of places like Australia, Moreton-Robinson has famously argued, is upheld by a logic of possession: a compulsion to extract, own and protect that underpins the practices and knowledges that sustain white patriarchal sovereignty. How, Patterson asked himself, might a person of settler heritage such as he make art on Country in a way that properly acknowledges or even disrupts this logic?

This background locates Patterson (and Cumming, whose work asks similar questions) within a broader transformation in Australian art history, and its troubled landscape tradition. Non-Indigenous artists are increasingly reading and heeding Moreton-Robinson’s message, and exploring ways they might return to the environment and materiality in a less possessive way. The goal is to find ways for settlers to live better on Aboriginal land. Or, as Simryn Gill has so elegantly put it: “How do we become from where we are?”

The necessarily collective nature of this endeavour was signalled at Patterson’s 2021 exhibition at Sydney’s Darren Knight Gallery, ½ to dust. Originally planned as a solo exhibition, Patterson instead invited artist friends to share the space, as a way of showing solidarity in hard times and articulating a shared sensibility.

This exhibition was Patterson and Cumming’s first collaborative engagement with the millstones. The work Redistribution (forbearing/forthcoming) (2021) (also on show at Verge) comprised a set of prints embossed with the words “DEEP HEAT,” which were produced by placing a die and paper between the millstones for the length of the exhibition—effectively turning the two stones into a printing press. Instead of attempting to represent the millstones, Cumming and Patterson found a way for the millstones to represent themselves: the resulting prints a set of almost photographic snapshots of the stones’ redistributed weight and downward movement.

A key aspect of the 2021 exhibition that is carried through to the present show is the concept of “exhaustion.” For Patterson, the cumulative impact of covid-19 lockdowns and more general artworld burnout had left him in a state of physical and mental exhaustion—a sentiment he found shared by fellow artists. Exhaustion is also, however, a material operation of possessive capitalism—the production of waste (exhaust) as the result of extraction and burning of fossil fuels. In the 2021 exhibition, Patterson expressed this link between the unsustainable consumption of artistic energy and the burning of natural resources with sculptures made of steam-diffusing car exhaust pipes.

The air quality conditions demanded by the millstones meant that Patterson’s exhaust sculptures could not be shown in the Verge exhibition. Instead, the gallery’s far wall is graced with a series of colourful sleeper-shaped markings, which Patterson produced by retooling his air diffusion sculpture into an instrument for spreading pigment across a surface. While in the 1960s the diffusion of pigment was understood as the final step in painting’s evacuation of all but its essential material properties, here Patterson insists on diffusion/exhaustion as a historical and political process.

The idea of exhaustion, then, contextualises the exhibition within twenty-first century extractive capitalism in a general and (literally) abstract sense. The millstones, by contrast, anchor the show in a much more specific and local history.

As Patterson and Cumming detail in the room-sheet, the millstones were used at a flour mill owned by the settler Thomas West. The mill was situated on and powered by a watercourse that became known as “West’s Creek” which, now enclosed, empties into Rushcutters Bay. The stones are made from basalt and, according to investigations by archaeologists James Flexner and Nicola Simpson at Patterson’s request, were likely transported here via sea from Germany’s Eifel district. The stones were only in use between 1812 and 1830, before they were rendered defunct by newer technologies.

While the exhibition’s exhaustion works evoke industrial extraction and dispersal, the millstones are instead artefacts of an earlier moment of colonisation, one driven less by industrial or urban development and more, as Dallas Rogers has recently argued, by rural practices facilitated by the circulation of goods and labour across the seas.

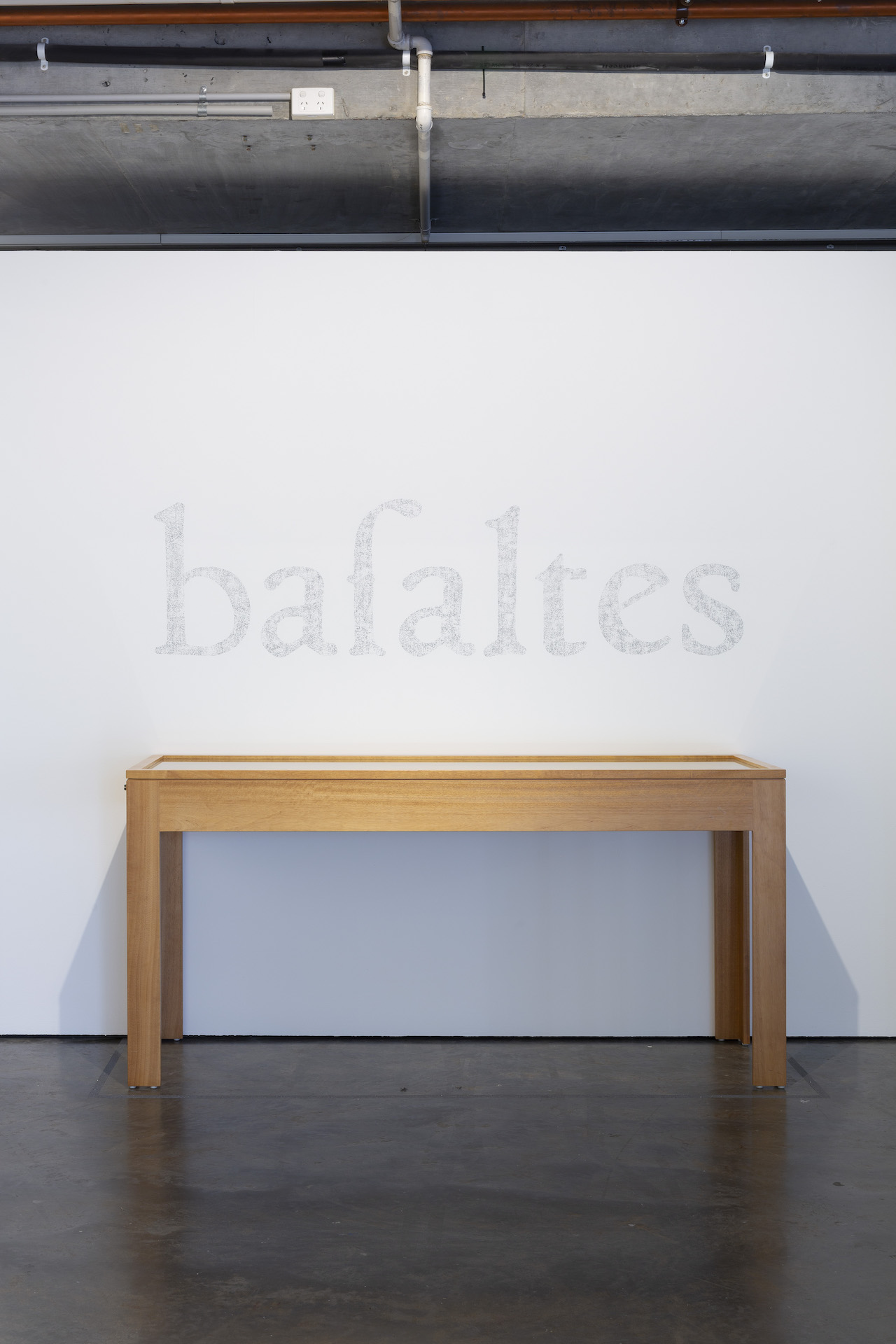

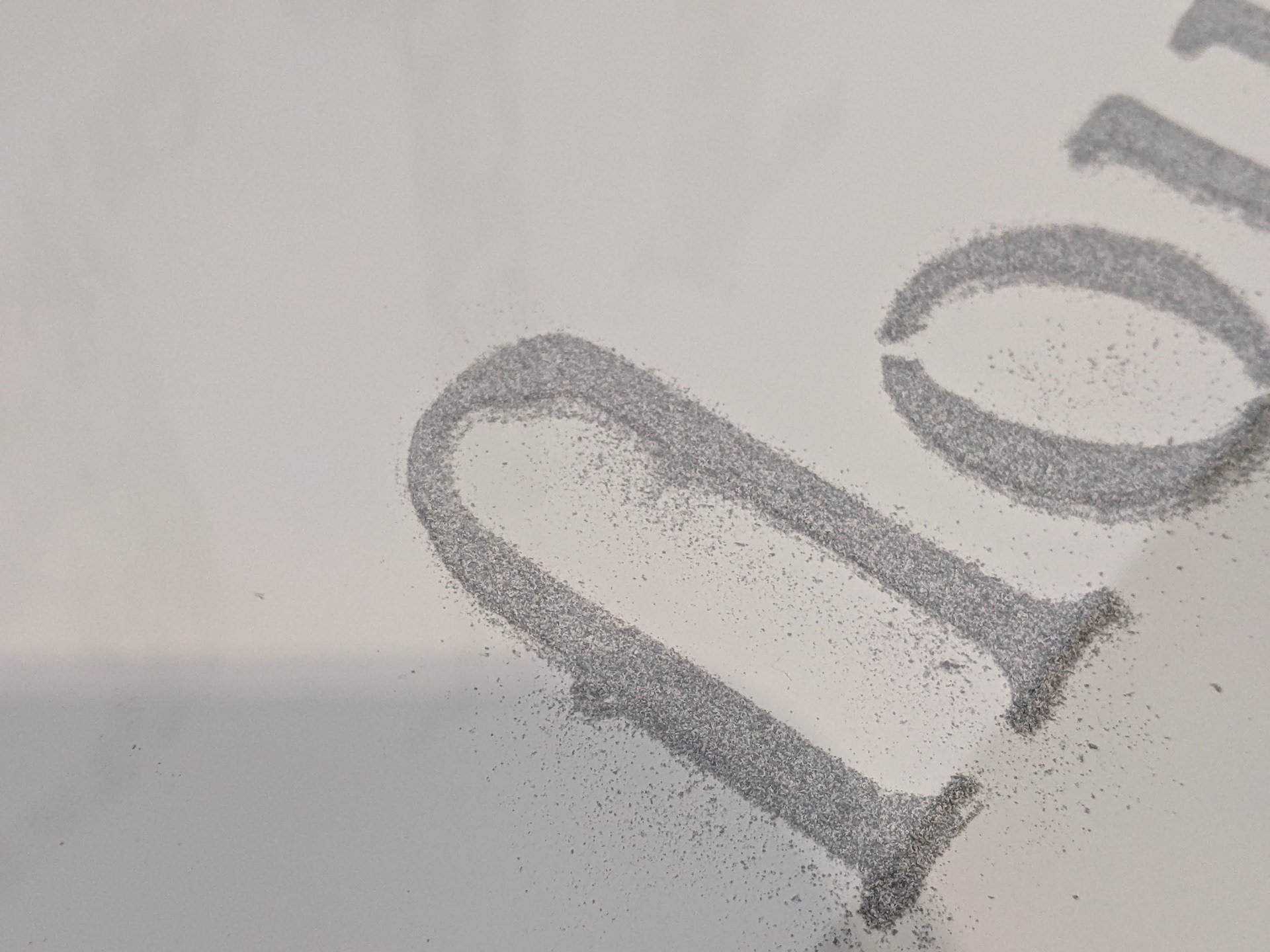

The circulation of commodities, labour and signs has been a focus of Cumming’s practice for some time. In his modest, wry poetic pieces, often published on Instagram, Cumming plays with the arbitrariness of signs, often drawing attention to moments where the smooth flow of language can be redirected or breaks down. In the Verge exhibition, directly adjacent to Patterson’s exhaust painting, Cumming has painted the word “basaltes,” which the 16^th^ century writer Georgius Agricola copied wrongly from Pliny the Elder, giving birth to the current word “basalt.” Cumming has sanded back the word to expose its material fragility, and used its traces to create another word, “flower” (the original spelling of the word flour).

Cumming’s experiments with signs and commodities are often enlisted in a project that he describes as “recessional aesthetics.” Here Cumming takes on the circulation of labour and money in the Sydney artworld, which he seeks to both expose and redistribute. In his 2019 Primavera showing, for example, Cumming enlisted MCA workers to staff Knulp, the small gallery he co-directs in Camperdown.

For Verge, Cumming has created Double Zero (2023), in which he has patched up a pair of holes left in the gallery wall from the previous show using “00” flour, mixed with water reclaimed from the Rushcutters Bay Stormwater Channel (West’s Creek present form). Cumming has deployed this work before (including in the 2021 exhibition) as a way of exposing the way the neutral flatness of the gallery wall is made possible by working hands. Here the work stands as a modest counterpoint to the millstone centrepiece, the work’s two Os mirroring their shape, and replicating their exposure of the infrastructural conditions of possibility for art’s display.

Ultimately, the exhibition title A redistribution is a misnomer. At work in the show are many redistributions—there is the redistribution of water and wheat to form flour, the relocation of the millstones from museum to gallery, the redistribution of the millstones’ weight to produce prints. There is also, as Moreton-Robinson would remind us, the brutal redistribution of Aboriginal people that occurred in sites like West’s mill, as they were removed from their Country, their subjecthood and environment recoded as possessions for settler colonialism to exploit.

Importantly, Cumming and Patterson resist ever pinning down redistribution, or framing it as a singular logic. Instead, their exhibition presents it as an ever-varying technique—what we might call, following Bernhard Siegert, a “cultural technique”—that is at work across the infrastructures that sustain settler art and life on Gadigal land that is still undergoing colonisation.

In Sydney at present, the triumphant arrival of Sydney Modern, and its multivocal survey of international art, risks a return to the sorts of totalising discourse that has, for better or worse, characterised the periodisation of contemporary art. Like Gill’s Clearing (a work recently on display at AGNSW that comprises a rubbing of a palm tree removed to make way for the new museum), A redistribution is a reminder of local histories and conditions, and the sophisticated strategies artists here are developing to deal with them.

The technique of redistribution is Cumming and Patterson’s significant contribution to the broader project of formulating non-possessive ways for non-Indigenous people to make art on Country. Their exhibition seeks to uncover its workings, to play with it, and to look for those moments where it stumbles and falls.

Nick Croggon is an art historian, writer and editor based on Gadigal and Wangal land. He is Events and Programs Officer at the Power Institute, and is completing a PhD at Columbia University, New York.