Melbourne Now

Amelia Winata

The NGV has been transformed into the shopping mall of the future, and design is its favoured language of commodity. For the 2023 iteration of Melbourne Now, an emphasis upon design was made apparent as soon as the viewer stepped into the atrium, with schematics for architecturally imagined dwellings and pieces from up-and-coming furniture designers paired with one another. The design aspect is peppered throughout, coming to an agonising crescendo with the design wall brimming with July suitcases and Tontine pillows. Why any of this needed to be included when Melbourne Design Week is only around the corner evades me.

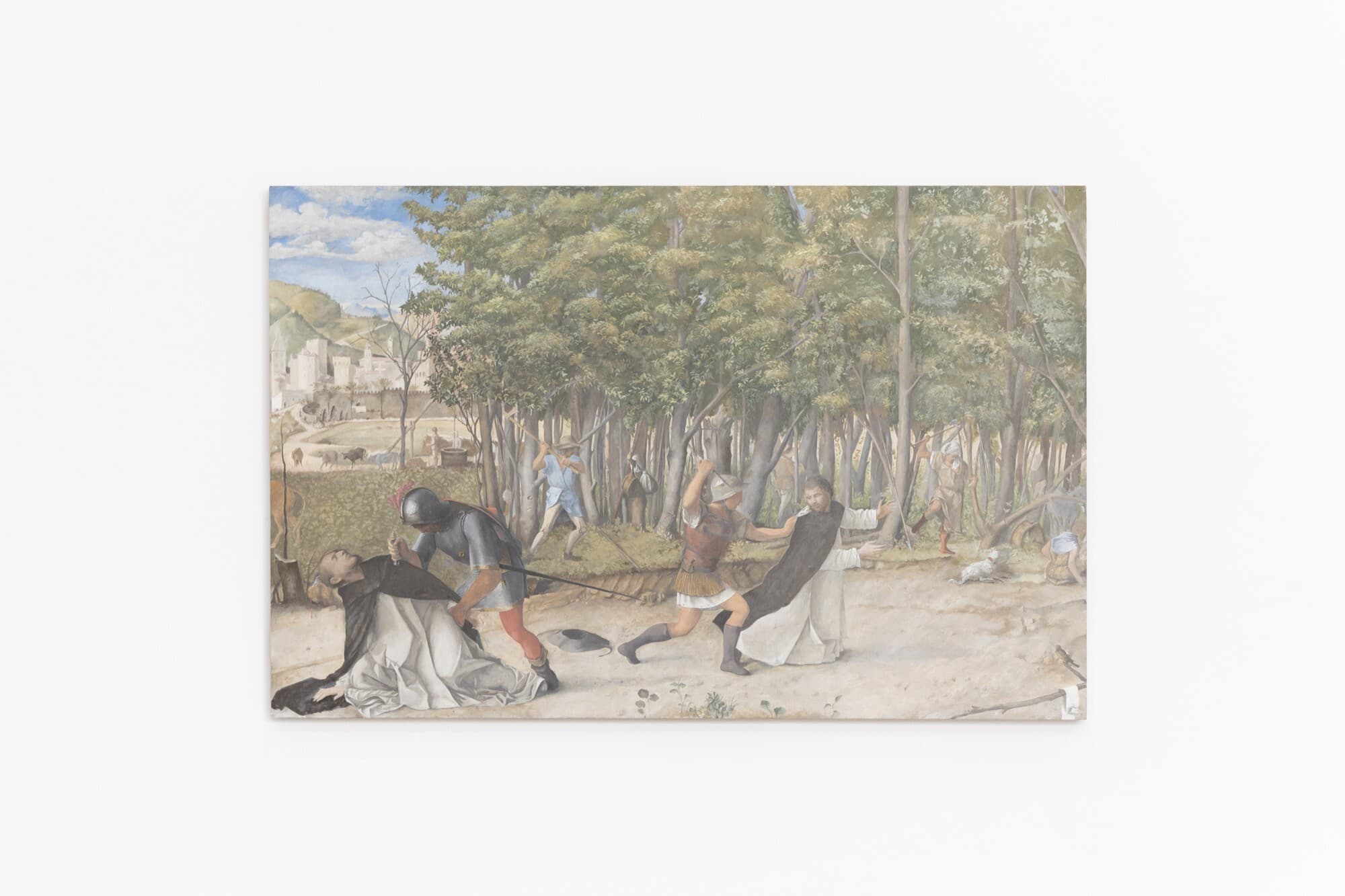

on display as part of the Melbourne Now exhibition at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne from 24 March to 20 August 2023. Photo: Sean Fennessey

Not only does design dominate Melbourne, but visual artists have been reframed as designers, or, at the very least, visual merchandisers who seduce us with images. Curators have attempted to create relationships between the design sections and artworks. A deliberate sight line links Megan Streader’s Sky Whispers (2023), a long, darkened gallery illuminated by light tape, and Fashion Now, the gallery dedicated to Melbourne fashion designers, as though the installation is some mockup of a cool runway design. Elsewhere, vision was privileged over substance, reducing three-dimensional objects to images. The logic of sculpture is repeatedly negated. This was evidenced in Nabilah Nordin’s trio of sculptures, pushed up against one another and mashed into a corner.

Melbourne Now is the NGV’s very own in-house shopping experience and Tony Ellwood is the client who wants to try before he buys. For the most part, exhibiting artists were commissioned to make new work (they were paid a combined artist and material fee to produce a new commission)—all while having the carrot of possible acquisition dangled in their faces. Many artists wait to hear if their works will be bought. And until then, they subdue their frustration at the disparity of pay (some exhibitors were paid handsomely, others nothing), and the micromanaging of the final works (many artists have reported being asked to change aspects of their works at the eleventh hour). If the work is purchased, the NGV will subtract the initial artist fee from the acquisition cost (for those not privy to the opaque machinations of institutional acquisition, this is, sadly, pretty standard practice). A number of those artists went beyond their artist fees, using personal savings to produce work of a quality high enough to be deemed acquisition material.

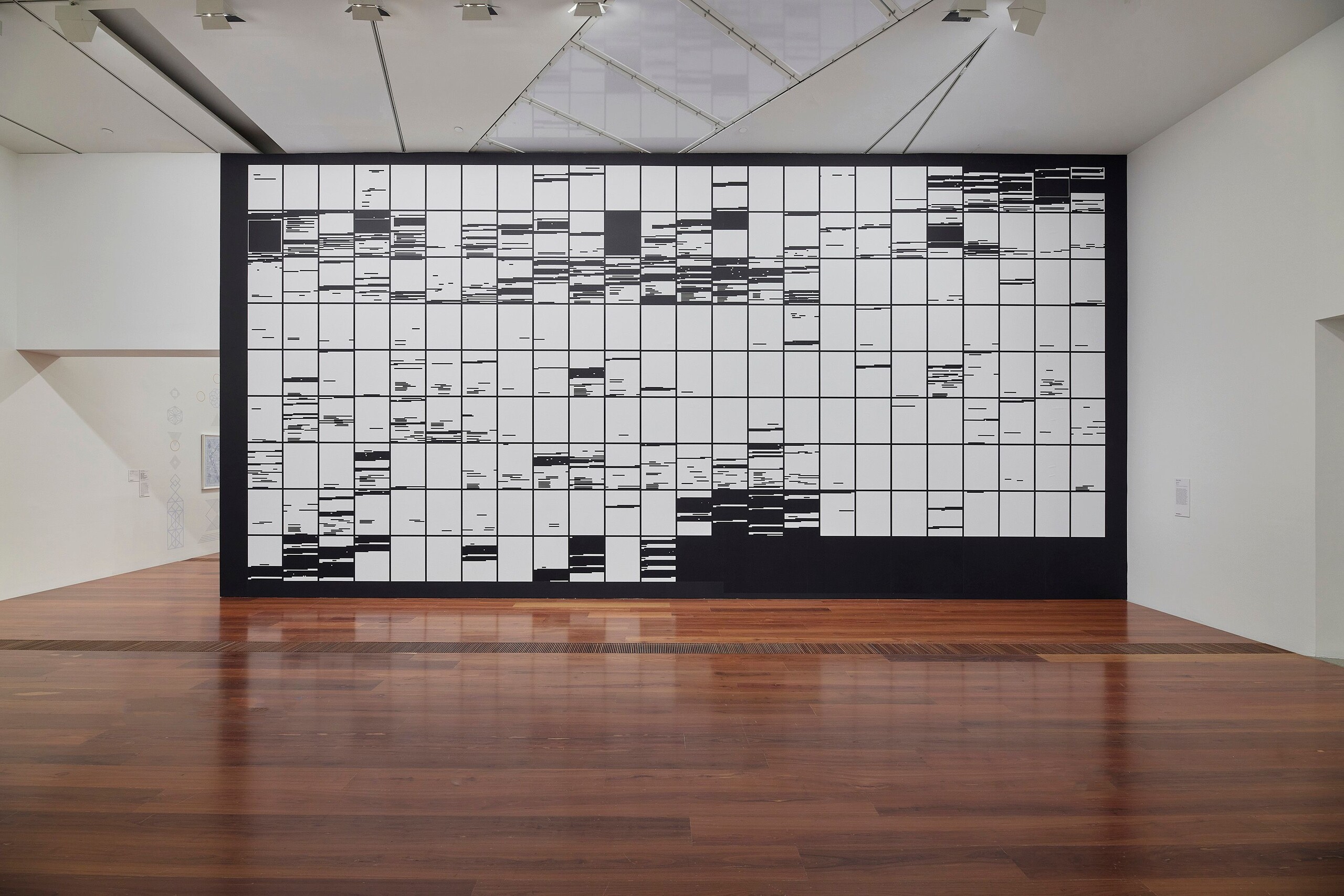

Of course, it is a well-known fact that money is not lacking at the NGV. Some years ago, the gallery allegedly spent one million dollars on a wallpaper machine. This acquisition means that every subsequent exhibition includes a jaunty wallpaper design. At Melbourne Now, the contraption earns its keep, looking to have been used by Atong Atem and Sean Hogan, amongst others. Hogan’s entire work, Volume 1 (2022), is in fact just wallpaper. One insider told me that there was “total chaos and staff on the verge of tears” in the lead up to the glitzy opening night. I imagine these teary-eyed staff members, delirious with lack of sleep, hastily pasting up wallpaper before the vernissage. Hogan’s work is laden with bubbles and creases and the panels are misaligned.

on display as part of the Melbourne Now exhibition at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne from 24 March to 20 August 2023. Photo: Sean Fennessy

A common formal characteristic amongst artists who produced large-scale installations is the multiple—see Jan Nelson’s windchimes (Black River Running #14: 33.54 minutes, 2020–22), Jenna Lee’s paper lanterns (Balarr (To become light), 2023) and Hannah Gartside’s mechanically-activated fabric sculptures (Forest Summons (for Lilith), 2022–23). The latter is a near monochrome and uniform reworking of Gartside’s colourful and varied 2022 Primavera installation. In and of themselves, these works are totally palatable, even likeable.

But the repetition of form across the galleries made me wonder if these artists were directed to extreme versions of their artworks, or if the install exacerbates the reproductive logic. Viewing these works, it’s impossible not to come back to the enormous design wall that featured dozens of identical products to create a grid-like formation. Indeed, the multiple insinuates modularity and reproducibility, themes that sit firmly within the free market logic of Melbourne Now’s latent shopping theme. I can see it now. Ellwood slowly wandering the galleries of NGV Australia, followed by a lowly shop assistant—sorry, curator—with notepad in tow, as he takes his pick of the works that will make it into the permanent collection.

Amelia Winata is a contributing editor at Memo. She is a PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne and the Curator in Residence at Gertrude Contemporary.