The original geometric sanctuary screen has been removed post-renovation and heating ventilation has been added. Most original elements, including the bronze reliefs and stained glass behind the church altar, remain. Photograph by Caitlin Wong.

Mary Immaculate Church

Cormac Kirby

Coming into the main street of Ivanhoe on Upper Heidelberg Road, ten kilometres north-east of Melbourne on Wurundjeri Country, it’s hard to miss the Mary Immaculate Church.

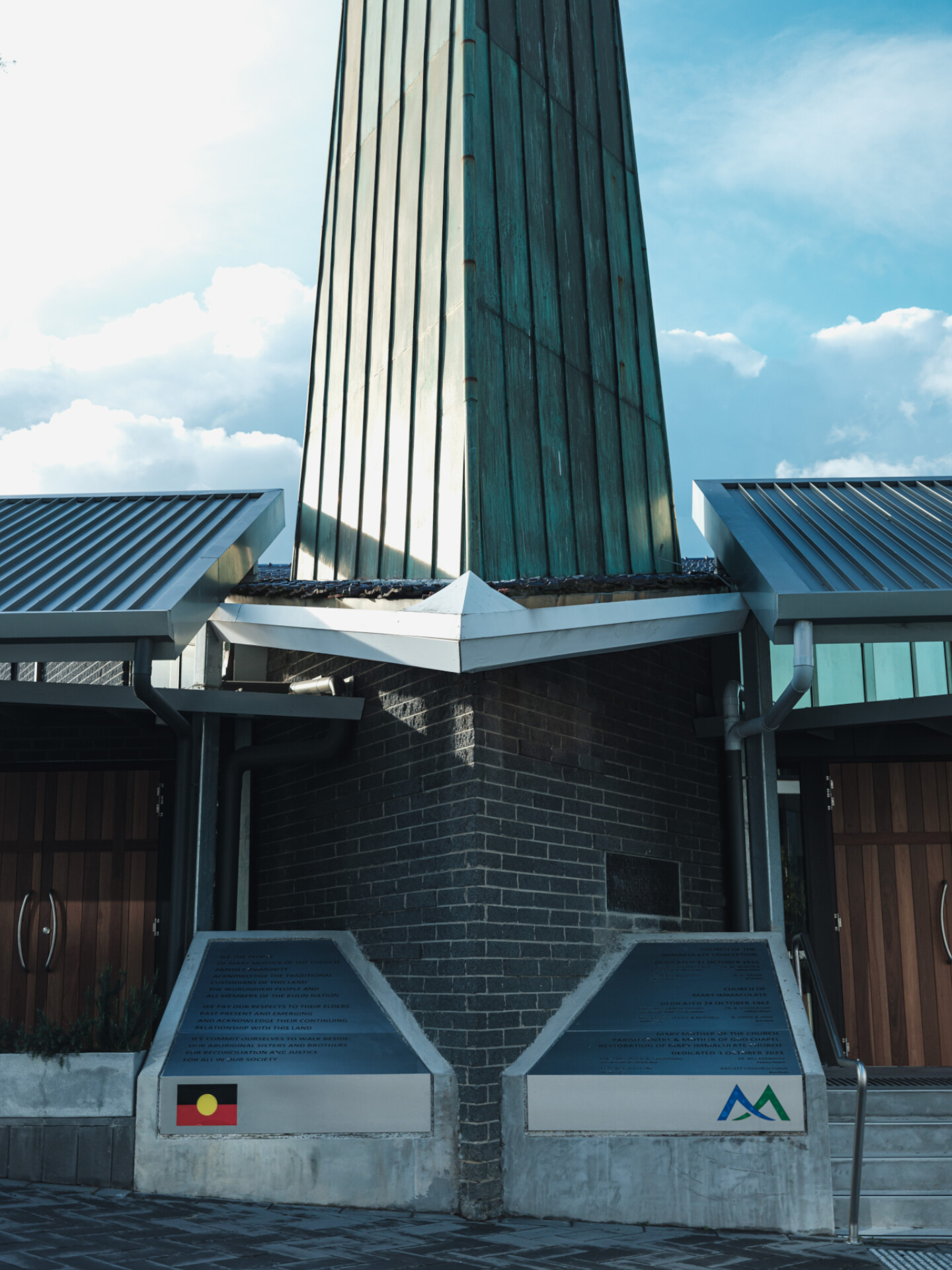

Framed at a street corner, just before the Ivanhoe shops begin, the mottled-green modernist church spire still draws adequate attention to the recently renovated building.

The new facade’s still-fresh mix of materials reflects the mix of opinions on the revamp of this church, which frustrated members of Melbourne’s architectural community, divided opinions of heritage institutions, and seems to have left its parishioners happy.

Exterior view of Mary Immaculate Church from Heidelberg Road showing the retained spire of the 1960 version by Mockridge, Stahle & Mitchell and the recent additions by FPPV Architecture surrounding it. Photograph by Caitlin Wong.

It would be easy to call the renovation of the Mary Immaculate Church a butchering.

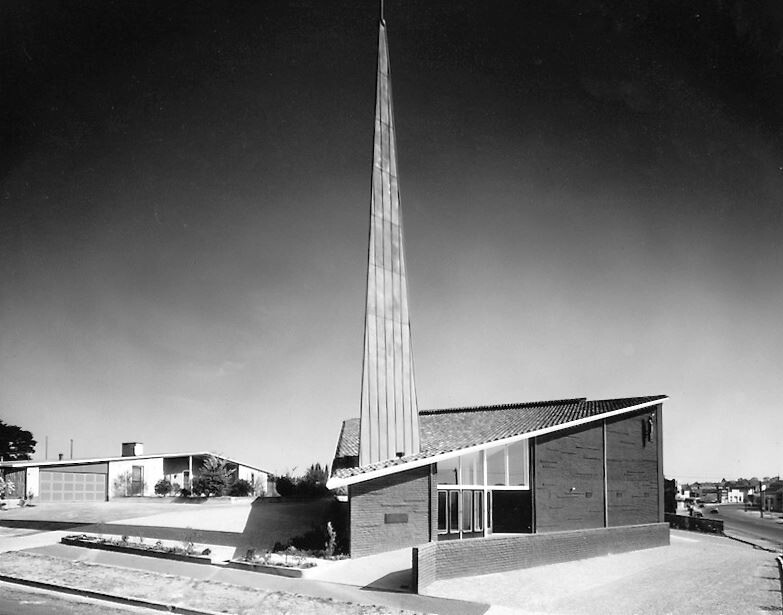

A previously intact vision of Melbourne’s post-war pre-occupation with reimagining places of worship—the original 1960 design by Mockridge, Stahle & Mitchell (of heritage-listed Carlton car-park and Troye Sivan “mid-century Melbourne oasis” fame) was an imposing sculptural edifice.

Exterior view of Mary Immaculate Church just after completion circa 1962, photograph by Wolfgang Sievers, courtesy of the National Trust of Australia (Victoria).

The focal point of the church—the spire—was, and still is, striking. A reinterpreted symbol of heavenly aspiration that made clear Mockridge, Stahle & Mitchell’s intention to create a modern vision for worship.

Renovated between 2021 and 2023, the original building has been unsympathetically treated, at least from the outside.

The once austere light-grey bricks and dark terracotta roof tiles of the post-war church are now swaddled, lying tamely in the centre of a larger, less imposing complex.

The structure and interior of the modernist church are intact, but the building has now been wrapped and partially buried in the expanded and recently opened Mary Immaculate Parish Centre.

Aerial view of the church prior to renovations in 2020 (left) and post-renovation in 2023 (right). Courtesy of Nearmap.

The building’s footprint has more than doubled with the kite-shaped church still the central piece of the new Parish Centre, but with built forms added to all sides.

Walking around the perimeter of the new Mary Immaculate Parish Centre, it is hard to not feel a little sorry for the once imposing modernist church, which has now been lost and neutered within a much more pragmatic but plain building.

Several community members, architectural publications, and the National Trust vied to save this building in 2018 from what can now be reasonably judged as aesthetic mediocrity.

At a Heritage Victoria Council meeting, the National Trust of Australia and community members faced off with Heritage Victoria and the Catholic Diocese of Melbourne over the significance of the 1960s building.

The debate at the hearing centred on the Mary Immaculate Church’s individual contribution to the heritage of post-war church design in Victoria.

The National Trust and community members wanted the building listed and preserved on the Victorian Heritage Register, while the Heritage Council and the Church argued against the restrictive controls associated with the listing.

The iconic spire pierces through the roofline of the Mary Immaculate Church. Date and photographer unknown. Photograph courtesy of State Library Victoria.

The original modernist church, intact until 2020, undoubtedly contributed to post-war church design (whether it was individually significant was the primary question). The 1960 design spoke not just to an architectural revolution in church design, but to a liturgical revision of worship.

In the early 1960s, the Second Vatican Council the Catholic Church re-imagined its ceremony—deserting Latin as the language of mass, revising the intricate rituals, and re-thinking how the space of a church functioned.

The unusual external shape of Mary Immaculate optimised engagement within the church interior. The kite-like shape enabled a non-traditional horseshoe-shaped seating pattern that put each parishioner within the direct eye-line of the priest.

There was to be no more dozing off in the back pews to the crooning sound of medieval Latin (something my own grandfather reportedly enjoyed). Instead, churchgoers were to be engaged, enlightened, and uplifted in a new type of Catholic mass.

The fresh modernist vision flowed from the structure of the church to the artwork inside, where renowned local artists were commissioned to design re-interpretations of classic ecclesiastical decorations.

Matcham Skipper of the Montsalvat artist colony designed a set of brutalist Stations of the Cross, which still line the perimeter of the renovated church.

Interior photograph taken in 2024 within the modified 1960 interior showing the 2023 modifications and the bronze reliefs by Matcham Skipper from the 1960 version. Photograph by Caitlin Wong.

Herman Hohauss, a sculptor, produced an eerie bronze statue of the Virgin Mary, while artist David Michael Shannon created a set of simple, geometrical stained glass for the church naves.

Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell, who designed other now heritage-listed re-interpretations of church buildings – like St. Faith’s in Burwood – were on this journey, and were closely involved, with John Mockridge himself designing a geometric sanctuary screen for behind the Mary Immaculate altar.

However, at the conclusion of the hearing, and to the dismay of the National Trust and many heritage-minded, Heritage Victoria ruled that the modernist Mary Immaculate Church did not satisfy any of the six criteria that could qualify it for a site-specific heritage protection.

John Mockridge’s original sanctuary screen was removed as part of the renovation. Photograph by Paul Atkinson, courtesy of the National Trust of Australia (Victoria).

The parish’s own decision to compromise the heritage of the Mockridge, Stahle & Mitchell church was, in a way, much simpler.

By the 2000s, the building had become almost completely impractical. The building was almost impossible to heat, costly to cool, and had no internal toilets—not ideal for ageing attendees.

Primarily, though, the building was needed to serve a different function—a new centre for three Ivanhoe churches: Mary Immaculate, St Bernadettes, and Mother of God. All designed by Mockrdige, Stahle & Mitchel in the early 1960s, and all of which were being forced to amalgamate due to declining church attendance and ever-rising maintenance costs.

The parish, being asset-rich but cash-poor, decided to focus its efforts on the Mary Immaculate site.

In an asset consolidation exercise, the parish divested their two other Ivanhoe churches (St Bernadette’s and Mother of God) with associated land-holdings, including school buildings, a parish priest’s house and tennis courts.

While procuring the design for the new consolidated Parish Centre, the parish priest, Bill Edebohls, told me he was encouraged to demolish the existing building in order to create a blank slate.

Keeping the interior of the modernist church intact was a decision, the priest says, that was a recognition the modernist design could connect with the faithful in a way a traditional narrow, rectangular hall could not. The building is now thermally comfortable, a little confused (with a modernist church buried inside) and truly post-modern.

The original geometric sanctuary screen has been removed post-renovation and heating ventilation has been added. Most original elements, including the bronze reliefs and stained glass behind the church altar, remain. Photograph by Caitlin Wong.

The new development spans three levels. At the northern end of the original church, there is a new street-level entrance and parish office facing Lower Heidelberg Road. The parish office doors address the street, designed to encourage walk-ins and greater interaction with the Ivanhoe community.

The modernist church itself now forms a mezzanine level. The original entry point on side street Waverly Avenue remains, but new office spaces have been attached to the original eastern facade, as well as a new gathering space, complete with a commercial kitchen on the western facade. The gathering space is designed for multi-purpose use, including school functions and wakes, and can be used as an overflow for the church, with a large television live streaming the services inside.

At the northern end of the church, there is also a second storey above the new street-level parish office with more office spaces, archives, and a private apartment for the parish priest (who lost his house in the big sell-off), and a new industrial-sized air-conditioning unit, which is critical for heating the once frigid church, but whose impressive mass also featured recently at the centre of a VCAT battle between the church and a nearby apartment building.

Mother of God Chapel, one of the new additions to the Mary Immaculate Parish Centre. Photographs by Caitlin Wong.

The modernist Mary Immaculate Church was an impressive, sculptural edifice. The new Mary Immaculate Parish Centre is a compromise, almost a retreat—less idealistic and more comfortable—like a revolutionary film now censored.

The modernist church does remain, albeit in a reduced, redacted form. The kite-like shape of the original building has been swallowed, with even the interior somewhat compromised—John Mockridge’s towering gothic sanctuary screen was removed during the renovation.

The value of these modernist places of faith across Australia is only now beginning to emerge in the minds of the heritage-inclined.

The fact that only eight such buildings have been heritage listed across Victoria, was referenced frequently by the National Trust in the Heritage Victoria hearing.

They are scattered across suburbia, with approximately 260 modernist places of faith built in Victoria between 1950 and 1970.

Original spire and the two new wings attached the east and west facades of the original building. Plaques at the entryway acknowledge the traditional owners and architects for the new building. Photograph by Caitlin Wong.

Interestingly, these buildings seem to be more venerated by the mainly secular architectural and heritage community than by parishioners who still attend their masses.

Their status as moments of architectural salvation in the dreaded monotony of Australian suburbia seems to give them an almost sacred aura—yet, usually, not as strongly to those who worship within them.

Ultimately, Melbourne has lost the integrity of a rather unusual and striking modernist church. Mary Immaculate’s failure to be listed on the Victorian Heritage Register, it could be argued, is more of a blessing than a curse.

View of Mary Immaculate Church in street context of Heidelberg Road mid-way through the renovations. Photography courtesy of Google Maps.

To entertain a counterfactual, given the financial difficulties facing the parish, if the church had been heritage listed, it’s likely the parish would have had to double down—sell the church, capture the value of the prime Ivanhoe land and focus on one of their other sites. To have the church listed, and likely force the community for whose use it was built to abandon it, would have been a strange outcome.

In that scenario, we probably would have been left with another post-modern, yet less appealing, compromise—a left-over, modernist sculpture in the form of a church, perhaps gracing the entrance to another towering Ivanhoe apartment condominium (with lovely hilltop views).

Cormac Kirby is a writer and urban planner.