Lili Reynaud-Dewar, TEETH, GUMS, MACHINES, FUTURE, SOCIETY / Alicia Frankovich, Exoplanets

Anna Parlane

The paired exhibitions currently on show at the Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA) are linked by the figure of the prosthetically enhanced, composite or permeable body. Alicia Frankovich's Exoplanets, 2018, and Lili Reynaud-Dewar's Teeth Gums Machines Future Society, 2016-18, both explore territory that can be described as post-humanist feminism. It's an interesting and curatorially astute pairing, not only because of the similarities in the two artists' interests but also because of the apparent difference in the politics of the two bodies of work.

Frankovich's practice has developed around the intersection of sculpture and performance, exploring the latent energy in both bodies and things. In recent years, however, her work has taken a new direction. Her (Dome Perspex Light Sculpture) (Not Yet Titled), 2018, is a good example. A transparent perspex pod that looks like a futuristic baby incubator contains a gleaming pile of golden omega-3 capsules. Hit by a projected stream of light, the capsules throw kaleidoscopic patterns onto the opposite wall. In contrast to Frankovich's earlier work, the theatricality of this installation tends more towards the staged image than the performative body. The patterns of light refracted through the translucent omega-3 capsules create an image that is transcendently medical: it seems to display the health-giving contents of the capsules in microscopic detail. Omega-3 is crucial to our health, but because it is not produced within the human body it must be ingested. Frankovich's auratic image of this substance speaks to our bodies' reliance on externally sourced chemical compounds and micro-organisms.

This point is reiterated in the adjacent video Exoplanets: Probiotics Probiotics! 2018, which displays microscopic footage of probiotic agents in the trendy fermented milk drink Kefir. The image collapses together macro and micro perspectives. The pale wrigglers on the screen, swimming through their deep indigo-coloured environment, could equally be unusually mobile heavenly bodies in a vast galactic system, or sperm anxiously seeking ova. The work points out that our bodies are a symbiotic composite of multiple parts, a galactic-scale ecosystem for microscopic life.

What I am describing here is not the common futuristic fantasy of technological post-humanism: a superhuman body armoured against physical vulnerability by technological enhancement. Although Frankovich's references to the naturopath-approved lifestyle of the urban hipster—yoga pants, omega-3, probiotics and purple carrots—could be seen as a version of this progressive mythology, technological post-humanism tends more towards the hope that technology will save us from our organic mortality. In other words, it is a narrative about culture's triumphant supercession of nature. The post-humanism that both Frankovich and Reynaud-Dewar explore is one that recognises no meaningful distinction between nature and culture. The post-humanist body is a synthetic assemblage of interpenetrating entities. It refuses the humanist and anthropocentric myths of self-sovereignty and discrete individualism by acknowledging our real symbiosis with other things: animate and inanimate, tangible and intangible.

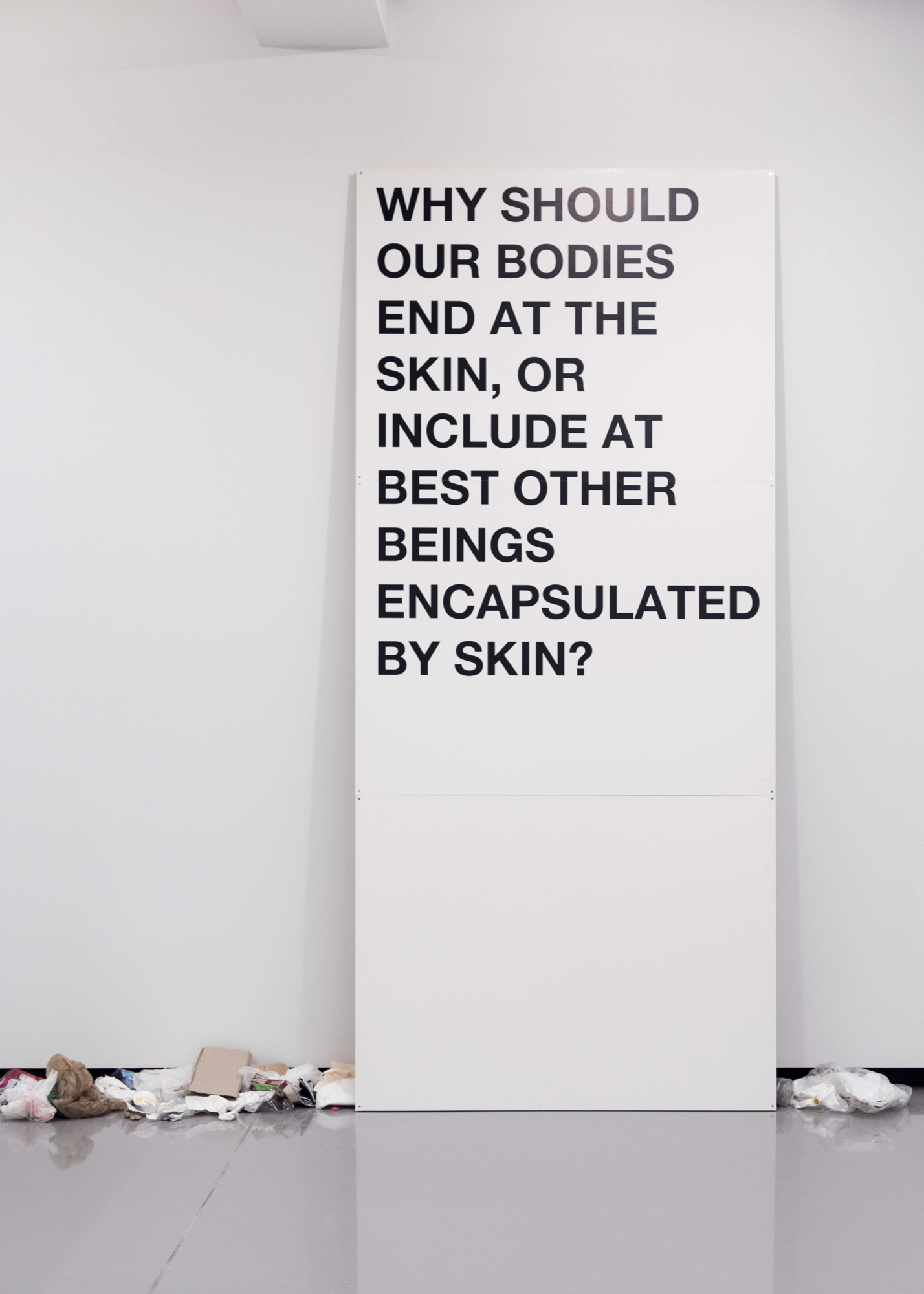

At the most obvious level, this is evident in the fact that Frankovich and Reynaud-Dewar have both assembled loose constellations of apparently very different things in order to discover or construct connections between them. Frankovich's works describe instances in which things imitate, transform into or are ingested by other things. In the animated video in her large installation Outside Before Beyond, 2017-18, for example, green Space Invaders-style pixels fluidly reconfigure themselves across huge shifts in scale: a spaceship becomes a sub-atomic particle becomes a galloping giraffe. Reynaud-Dewar's Teeth Gums Machines Future Society also combines a bewildering array of references: teeth, trash, hip-hop, the political history of Memphis, stand-up comedy and pioneering post-humanist feminist writer Donna Haraway's 1985 text 'A Cyborg Manifesto'. The key link, for the artist, is the “grill”: a kind of jewellery worn on the teeth that has niche popularity in African-American hip-hop culture. For Reynaud-Dewar, grills are a metallic cyborg-style bodily enhancement that also speak about the construction of cultural identity. As a white artist, however, by using the grill she ventures into the racially charged terrain of cultural appropriation.

The video component of Reynaud-Dewar's installation features interviews with several Memphis comedians fitted, for the project, with custom grills. Their commentary is edited together with drive-by footage of Memphis streets cut to a pulsing hip-hop beat, the labour-intensive process of crafting a grill, and a performance the artist staged in the Memphis sound shell. The comedians complain about how uncomfortable the grills are, while Reynaud-Dewar's camera captures in close-up their obvious difficulty speaking. As their mouths contort around the foreign object introduced into the sensitive space between teeth and lips, their physical discomfort parallels the political tension in Reynaud-Dewar's project. The artist has mined the culture of a group that is not only foreign to her as a white European, but has historically been subject to violent disenfranchisement as a result of their exoticisation and fetishisation by white Europeans. The precise nature of Reynaud-Dewar's interest in Black cultures and histories remains an open question and, to my mind, an uncomfortable one. My discomfort was shared, apparently, by the work's participants. African-American comedian Darius Clayton tells the artist that his initial reaction to her project was “Are they trying to gentrify the gold teeth now? Like, can we not have anything?” It's a good question, and it threatens to overshadow Reynaud-Dewar's effort to, in her words, “create a new meaning” for the grill.

Reynaud-Dewar's work does succeed, however, in dwelling in this discomfort. Like the camera fixating on her interviewees' mouths as they struggle to adjust to the grills, she has focused her work on this ideological fracture. In this she is true to Haraway's 'A Cyborg Manifesto'. For Haraway, the cyborg figures a refusal of organic wholeness. It stands in opposition to any sense of original unity or coherence, the supposedly “natural” order of things invented by patriarchal humanism that underpins hierarchies of race, class and gender. Haraway's cyborg is an antagonistic composite, a post-human construction forged out of the fractures and failures of past ideologies. The question is: in a post-human collectivity that rejects the organic unity of a discrete body (whether this is an individual body or a collective social or cultural body), is it possible to take account of a disparity in power? In other words, can post-humanism, with its fluid interchanges between self and other, adequately acknowledge histories of oppression? Can a white French artist use grills in her work without subjecting them to the cultural death of gentrification?

By focusing on material and bodily transformations and assemblages, Frankovich seems to have sidestepped the fraught politics that Reynaud-Dewar has tackled. But as the juxtaposition at MUMA clearly demonstrates, the two are related. Both artists attempt to demonstrate a different way of perceiving the relationships between things: self, other, bodies, objects, myths, histories and ideological frameworks are all, in these artists' works, enmeshed in continual interplay. And it is perhaps in this theatre of multiple views that Frankovich's work offers a possible response to the problems Reynaud-Dewar raises.

Frankovich's Outside Before Beyond is elaborately choreographed. The work comprises an ambient electronica soundtrack, a double video projection beamed through cinema-proportioned fringe curtains, and several large scale images, rigged billboard-style on metal scaffolding, which create visual rhymes between legs, root vegetables, skins and tights. These elements are each smoothly illuminated in turn by a central, automatically rotating theatre light. The explicit theatricality of Frankovich's installation, like the staginess of the projected light in (Dome Perspex Light Sculpture) (Not Yet Titled), insists that the framework through which we view things is as worthy of examination as the things themselves. Habits of thought are the stage sets that shape perception. They make it possible, for example, to recognise the power dynamics at play in the exploitative gentrification of “authentic” African-American hip-hop culture. These frameworks, just like the objects they display, are both historically real and ideologically constructed. They are elements in the multiplicity of our shared reality—which, as Reynaud-Dewar makes clear, is far from frictionless. While this is certainly not a resolution (cyborgs don't promise justice), it seems like an important trajectory of thought worth developing.

Anna is a writer and occasional curator based in Melbourne. She is currently finishing a PhD at Melbourne University, and was previously assistant curator at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.