Light + Shade: Max Meldrum and his followers

Jarrod Zlatic

The work of Max Meldrum—and the circle of artists who adopted his tonalist theory of painting in the decades after the First World War—tends to be both ever-present and also unknown. His theory was a provocative and appealing avenue for artists that became a major component of Australian arts culture in the inter-war period. The method rejected all drawing and design stages, painted directly from observation through squinted eyes and predominately executed on board (valued for its sturdy flatness). The resulting works, informal and realistic, at times inadvertently border on abstraction. Outlines were forbidden and large masses of unbroken colour often dominate, while clusters of dissolving tonal shades and single brushstrokes provide the few points of detail and definition.

Although consistently present in Australian art historiography and included in permanent collections as timepieces, they have been increasingly remote in mainstream understandings of Australian art since Meldrum’s death in 1955. Indeed, as far as I am aware, the last time Meldrum himself was the subject of an exhibition by one of the major institutions was at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1961. The retrospectives of the Meldrum circle that do inevitably come around tend to be hosted at regional or private galleries.

Much of the on-going interest in the Meldrum circle has been due to Clarice Beckett and her enigmatic and moody landscapes. Beckett was Meldrum’s star pupil and has slowly been admitted into the centre of Australian art since her re-discovery in the 1970s. She was the subject of a comprehensive retrospective by the Art Gallery of South Australia last year (curated by Tracy Lock-Weir, who was also behind AGSA’s Misty Moderns: Australian Tonalists 1915-1950 in 2008), which one would suspect was the impetus for the current show held at the Art Gallery of Ballarat, Light + Shade: Max Meldrum and his followers.

The past retrospectives on the Meldrum school have tended towards a curatorial approach that treated the tonalist works as hermetically sealed, displayed on their own closed circuit. Refreshingly, the current show curated by Louise Tegart makes a break with this approach. Drawn almost exclusively from the gallery’s own collection, the choice of works goes beyond tonalism proper to include paintings from artists who studied under Meldrum but subsequently moved away from his strict precepts.

The influence that Meldrum had on Australian art has tended to focus on his impact on the trajectory of modernist painting within Australia. While he was personally an anti-modernist modern, Meldrum’s systematic theory of painting (what he called a science) was a phase that many of the Australian modernist painters of the 1920s went through before their embrace of a modernism proper. Here Arnold Shore is the chief representative of this tendency. He is featured prominently in six paintings across the three rooms of the current exhibition, five of which are from long after his move away from tonalism in the early 1920s. His diminutive landscape from the 1950s are perhaps the most remote from Meldrum’s style. The lumpy, ecstatic impasto is excessively applied to the point of incomprehension. The hillside scene looks as if it is melting and threatening to drip down onto the gallery floor.

Interestingly the exhibition also provides a view into how Meldrum’s influence worked its way into painting that, at first sight, seems closer to the popular interwar landscape tradition. This can be seen in the works of the once successful but now almost completely forgotten landscape painters A. E. Newbury and William Rowell. While incorporating the tonal method, these artists produced large-scale canvas works in the higher key yellows and blues of Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton which were consciously rejected by Meldrum for their unnaturalness. These landscapes in the exhibition depict scenes of a far wider scale and more open feeling than the typically sheltered or lush scenes of the other landscapes in the show. Newbury in particular seems to have favoured bush scenes that embraced both the sublime and sentimental, with the recurring motif of mother and children enjoying an afternoon in nature, dwarfed by the surrounding bush. The Meldrum circle is often placed in opposition to the so-called Gum Tree school. Meldrum’s own quasi-socialist pacifist politics and alternative model of the Australian landscape—small and slight—can be thought of as a repudiation of the heroic, nationalist landscape tradition. Yet it is easy to forget (because of changing taste and the shifting historiographical perspective on Meldrum) that his teaching method still fed back into now quite unfashionable and populist approaches to painting throughout the middle of the century that now clutter the salerooms of auction houses and backrooms of regional galleries.

While numerous “strong” painters were attracted to the tonalist method, the school was also a haven for amateurs and dabblers. The exhibition features works by obscure Ballarat locals who studied under Meldrum. The portrait of a violin player by Dorothy Edwards is decidedly scrappy, though the oblique, craggy post-mining landscape by Irene Hewett is intriguing in a way that best exemplifies the style. A cliff face is rendered in a limited palette of mostly soft pinks and brown, unspooling like jagged cloud patches and vapors with lines of green vegetation attaching themselves through paint daubs like tufts of lint.

It is these marginal works that point to the actual long-term impact of Meldrum more so than the grand landscape works. The Meldrum tonalists have a long tail of influence stretching well into the early 1990s and beyond. Meldrum’s students taught students (e.g. Ron Crawford and Alan Martin in Melbourne, Hayward Veal in London and Sydney, Percy Leason in Staten Island, NY, Joseph Allworthy in Chicago) whose students continued to teach the tonalist method to students who still teach today. The notion of the student was pertinent for Meldrum, who saw painting as an endless learning process (to Meldrum even the greats such as Rembrandt were classed as perpetual students). It was said of his teaching, not unlike his paintings, that his “last lesson was same as his first”.

The organisation of the paintings is by theme. The first room is focused on still life and landscapes, the middle room a mix of landscape and beach scenes, with the final room exclusively portraits. While the tonalist works themselves seem to invite a thematic hang, this curatorial choice tends to obscure the chronological shifts of the students who went their own way. It also dilutes the consistency of style that is a hallmark of the Meldrum method. This approach, combined with the limitations of direct association with Meldrum, leads to the inclusion of some rather weak works. The paintings by William Frater and AME Bale (representing both the modernist and conservative trends of “post-Meldrumites”) are especially unengaging, almost arbitrary in the context of the show, and detract from the more interesting angles elsewhere in the exhibition.

While his influence obviously runs through the majority of works on display, Meldrum himself is almost absent from the exhibition, represented by only four out of the fifty paintings on display. Yet due to the very nature of his painting theory, Meldrum’s complete absence would have made almost no difference to the show itself. Indeed, to search for aspects of personality in the row of impassive still-lifes in the first room—to determine what differentiates Harry Harrison’s creamy daffodils from Beckett’s earthy wattle and gum leaves from Alma Figuerola’s gladioli—is beside the point. Meldrum’s theory of painting was not just a painting method but also a philosophy around the combination of painting and observation that was infused with a dogmatic rejection of personal expression and feeling. This hostility to expression included a disavowal of all narrative and literary content in painting, a textbook Meldrumite work being completely unallegorical. This impassive, impersonal quality means that five paintings in the style could almost be equal to fifty. At their core many of these paintings are interchangeable, the artists to a degree irrelevant.

The restricted palettes and blocks of flat colour often result in remarkably rich paintings. The subtle gradations and vibrating blank spaces of unbroken wall, cloth, sky, ground, tree or sea rendered in single colours are entrancing and ambiguous. Yet they were conceived in resolutely anti-sensual terms. Meldrum wrote that treating art as a pure science of optics enabled art to transmit “more than blind sensual emotions”. This denial or transcendence of sensuality entails that the work of Meldrum and his many followers is in many respects bland. Yet this “blandness” is deliberate as his method insisted on impersonality as a form of ego-death. They are willfully mindless. Meldrum insisting of himself that he was an “interpretive, not creative artist”, and that “without clear sight there can be no clear thought”.

The tonalist paintings are notionally empty, concerned with nothing else but painting itself. They were strictly preoccupied with problems of order, space, proportion, light, shade, colour, etc. It is tempting to read the later interiors by Meldrum, painted as he became increasingly housebound (none of which sadly are present in the exhibition), as a surrender to more human concerns. The oblique depictions of empty chairs and figures, frozen within velvety genteel surrounds, is suggestive of icy domestic drama or ennui. Though this interpretation, I suspect, would be further over-determination on the part of the viewer: trying to fill the void of apparent meaning in these paintings through narrative content misses the point of their own internal concerns. The carpet, upholstery and drapes simply presented for Meldrum the same observational and depictive challenges as eucalypts and country roads had earlier on. Painting remained for him a militantly optical art, truly what-you-see-is-what-you-get.

This unrelenting insistence on impersonality and de-subjectification lends Meldrum’s theory of painting a quality closer to a painting machine than a painting method as such. The problems of subject, theme, style, etc., all became needless problems or questions for those that submitted. This approach to painting has typically seen comparisons with the camera. This is apt, not due to their realism, but to the off-the-cuff and sometimes awkward compositions that embrace a seemingly arbitrary form of image production.

It would appear today that Meldrum’s process can be seen as algorithmic or auto-generative, his painting machine being an endless content generator. The basic setting runs on the stock refrains of the easel painting tradition—en plein air landscapes and studio still-life studies—though ultimately open to whatever the eye sees. This is a cybernetic approach where the artist is jacked into a control and observation system of Meldrum’s design. Together they blankly scan empty streets, public parks, paddocks and lounge-room corners for new content like a security camera system. The artist co-mingling into a network of dispassionate eyes, each painting adding to an ever-expanding database.

This indifference towards content itself lends many of the works in the exhibition a timeless quality,incorporating both urban modernity and rural tradition. Automobiles and trams or electricity and telegraph poles are seamlessly assimilated as painting content. Laptops or data banks would simply be an optical event, no different to the old mill in the 1926 painting by AD Colquhoun or the spinning wheel in Polly Hurry’s Woman spinning (1944). The art critic J. S MacDonald’s complaint in 1925 that the “familiar and unfamiliar present no depictive difference” for the Meldrum circle can be seen as the very motor of the style.

This approach is timeless in an anti-historical way,so caught in a single moment that it is a moment of nothing. This contemporaneity, with its rejection of allegory or social comment, is distinct from the contemporariness of the 19th- century French realists who were influential on the Meldrum circle. Apart from the model of cars in Colin Colahan’s Elizabeth Street (1929), many of these paintings are only noticeably dated through their glittering, ornate gold frames (though the more recent acquisitions have opted for the “funeral black” frames that many of the works were originally exhibited with).

In this respect the tonalist’s works have more in common with the pure forms of, say, Ralph Balson’s Constructivist (1946), on display upstairs in the permanent collection, than any of the subsequent generation of figurative and social realists (indeed Ian Burn has described Colahan’s Elizabeth Street as almost “Constructivist in its clockwork precision”).

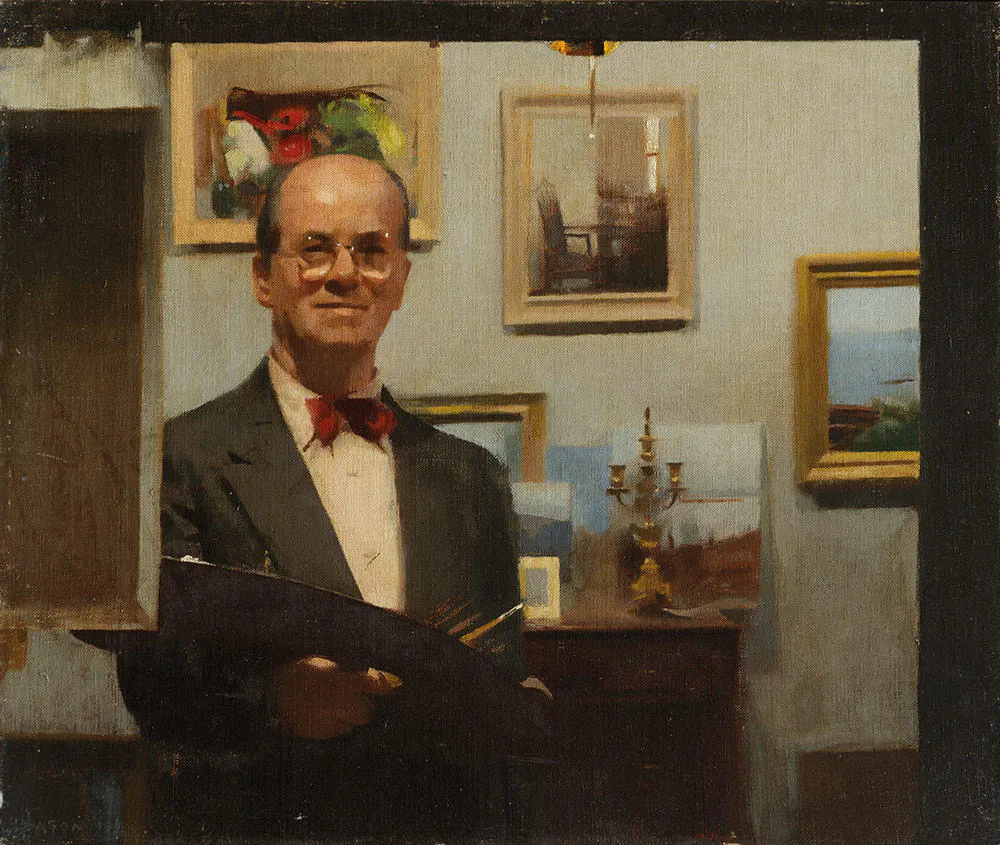

Yet Colahan is also an example of how Meldrum’s followers wrestled with the limits of de-personalisation. The best painters who emerged from this circle (Beckett, Colahan, Leason) produced paintings that developed upon Meldrum’s theory to create works with distinct individuality. Several paintings from Leason in particular show something approaching humour (Leason was at one time Australia’s highest paid newspaper cartoonist), which seems uncharacteristic of the soberness typical of the style. The lush scene of an Eltham pond with a putti ornament holds an air of serene fantasy, with the all-American rodeo cowboy in blue Western Yoke against a vivid field of pure orange; even the black bands running around the upper and right edge margins of one of Leason’s self-portraits-as-artist suggests a joke about the nothing point beyond optics. The black band beyond the mirror representing both a literal vision of black, blank space and the notional nothingness that is at the limits of vision. These black bands become a stand-in for the blank void of modernism itself that the Meldrumites held such a reactionary position towards.

The long tail of Meldrum’s influence on art teaching even had an impact on artists who sit beyond modernism as such. Ian Burn and Robert Rooney, usually considered among the chief exponents of the conceptualist break with painting in the late 1960s, had to navigate the impact of Meldrum on Australian painting. Burn’s experience was positive; he was briefly a teenage Meldrumite before enrolling to study at the National Gallery, and his mid-1960s paintings seem to have something of the tonalist’s systematic approach to colour. Rooney’s meanwhile was negative; he deliberately chose to study design at Swinburne Technical College to avoid the Meldrum derived-tonalism taught at the National Gallery Art School.

Yet there are even synergies between Meldrum and Rooney’s later 1960s paintings or his conceptual photography works such as Holden Park 1 & 2 (1970). Rooney’s droll, domestically focused works were preoccupied with the same themes of non-artistry, “blandness” and realism that anchored the Meldrumites, albeit in an ironic and inverted way. While the tonalists considered their photograph-like works to be an attempt to develop and heighten human vision, Rooney embraced the camera and process-based painting for their ”dumbness” and mindlessness. It is a shame the gallery did not pull down Rooney’s Canine capers VI (1969) from its current inclusion in a bizarre and totally inaccessible Salon hang above their main staircase (truly a triumph of decoration over display) and insert it here amongst the works as a sheep in wolf’s clothing.

Although the comparisons with the later conceptualists can seem dubious and perhaps forced, this correspondence can be pushed even further. Meldrum and the conceptualists both held doubts over the elevation and status of the creative artist, there being a synergy between Meldrum with Dale Hickey, who exhibited with Rooney and Burn at Pinacotheca. Hickey’s work Fences (1969) involved hiring a tradesman to erect a fence around the edge of the gallery’s walls, echoing sentiments in Meldrum’s book The Science of Appearances (1950)that “it can be said without exaggeration that the house-painter knows as much (about the mechanics of painting)…as the most accomplished artist”. Meldrum dismissed the technical side of painting as “relatively easy”, instead emphasising that “one must learn to think as a painter”. Yet while sharing this skepticism towards paintings in-and-of-themselves, the Meldrumites obviously remained true romantics, dedicated to the act of painting itself. Indeed, the Meldrum circle and its ongoing lineages still paint with the belief that painting never ended.

Jarrod Zlatic is a writer and musician from Melbourne.