Kieren Seymour, Autism, Bitcoin and the Four Seasons

Adelle Mills

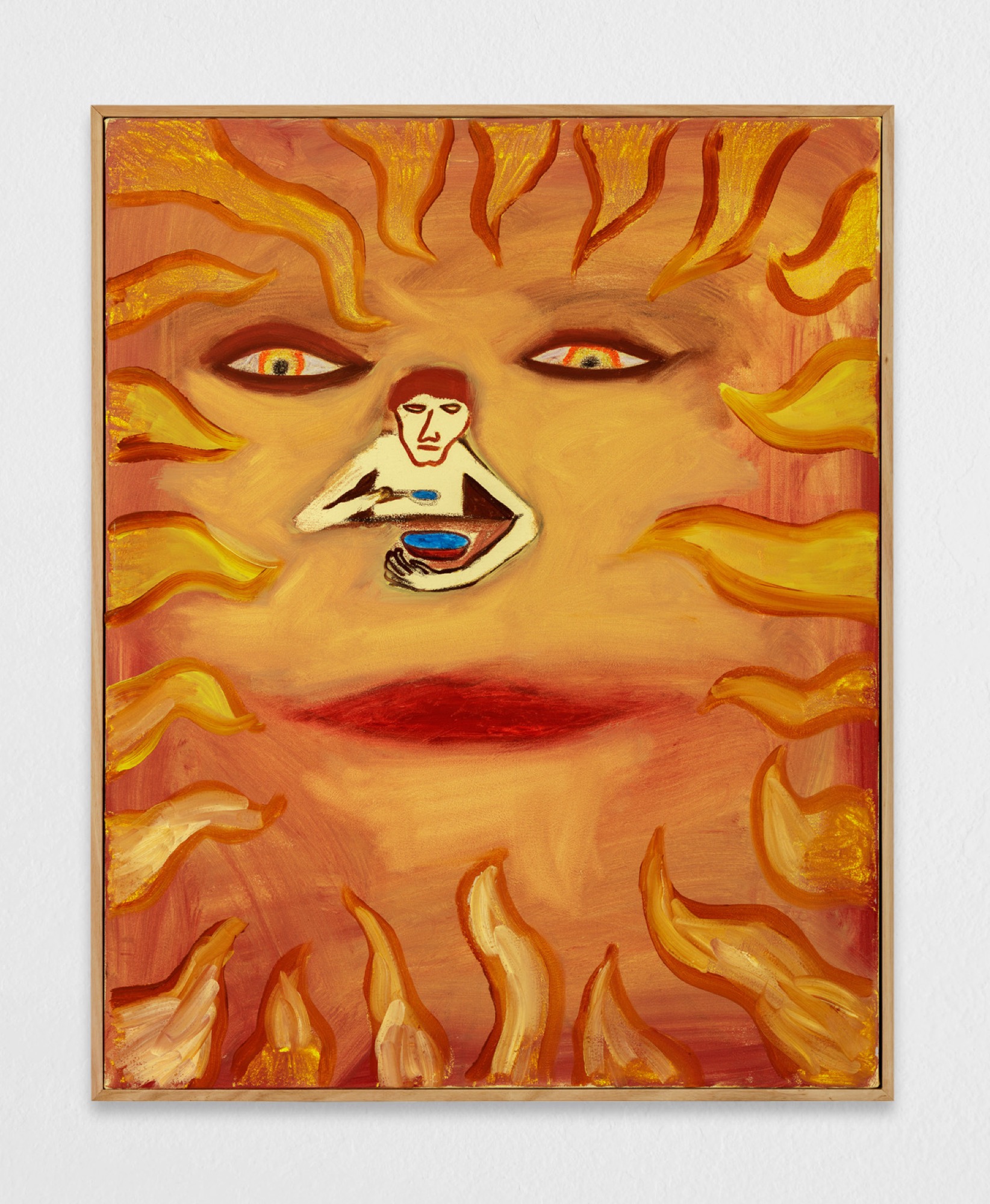

“O blushing sun, ashamed of my despair”, Phèdre cries, “Now, for the last time, I salute thy face”. Jean Racine’s 1677 dramatic tragedy follows the disgrace of its namesake Phèdre, who declares incestual love for her stepson Hippolytus. With the shame this brings, the older woman is consumed by a death wish so sour her desire turns to rage and betrayal. Daughter of Helios, the god of the sun, Phèdre’s patriarchal lineage is key to her pathological torment. Throughout human history the sun has been a Socratic allegory for goodness, vision and change, but it is because of Phèdre’s habitual avoidance of the downward gaze of the sun—“My face is hot, with my shame; / I cannot hide my guilty sufferings / And tears descend that I cannot restrain” —that we learn of the destructive power of the sun God and, through this, the power of taboo. While Racine deals with the more fundamental taboo of incest, Kieren Seymour’s Autism, Bitcoin and the Four Seasons, an exhibition of twenty-three recent oil paintings at Neon Parc in Brunswick uses seasonal motifs to confront the neurological taboo: that of being “different”. In this collection of paintings, the sun is a recurring axis from which the transmuting bodies depicting ‘Bitcoin’ and ‘Autism’ take their energy and guidance. Sometimes these figures rest beneath the sun’s hovering gaze; at other times these symbols of economic progression and neurological divergence appear to enter or hide behind the sun’s fractalised surface.

The four seasons appear as characters throughout this series of paintings, like close friends of the seemingly phantasmagorical “Bitcoin” and “Autism”. But it is these latter figures that become metaphors through which we encounter the mutable paradigms they each present. Seasonal forms and faces—some disfigured, others rendered familiar through reappearance—offer an allegorical structure for Seymour’s exploration of the refracting alignment of a singular and yet mutable emblem for growth and difference. Seymour’s Autism/Bitcoin figure communicates the Janus face: one who naturally changes like the ecological allegory of the four seasons, while providing passageway for birth and exchange.

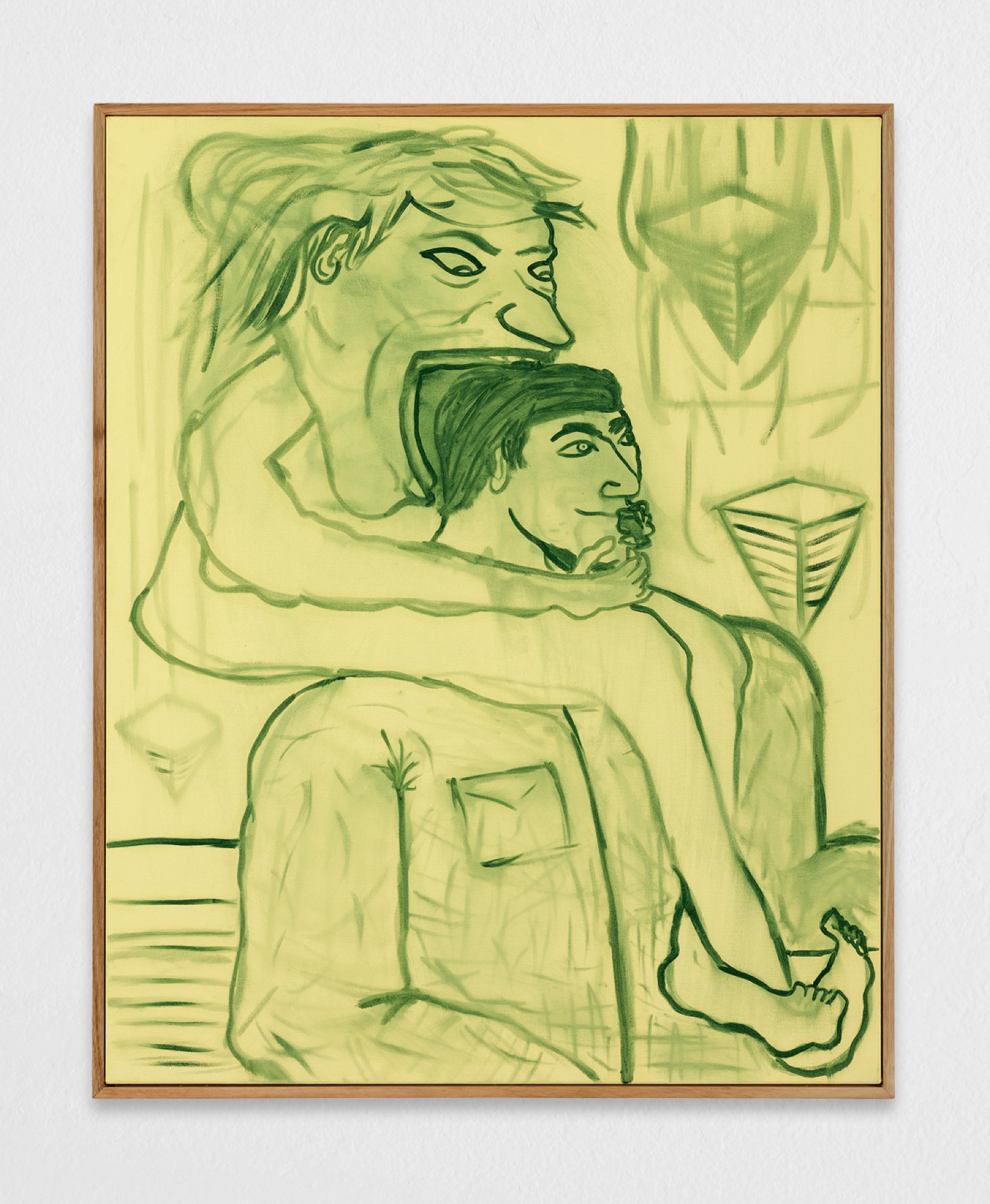

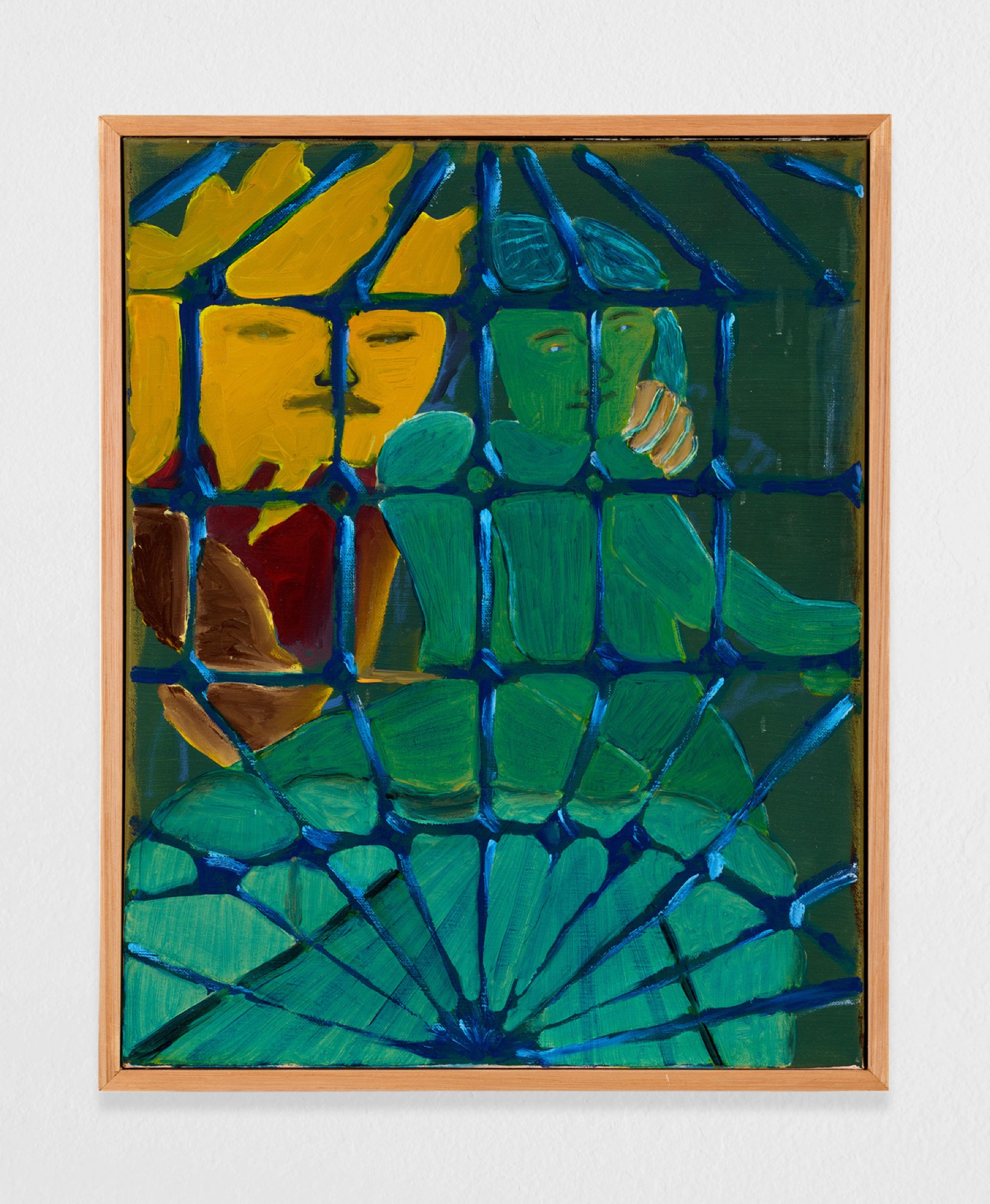

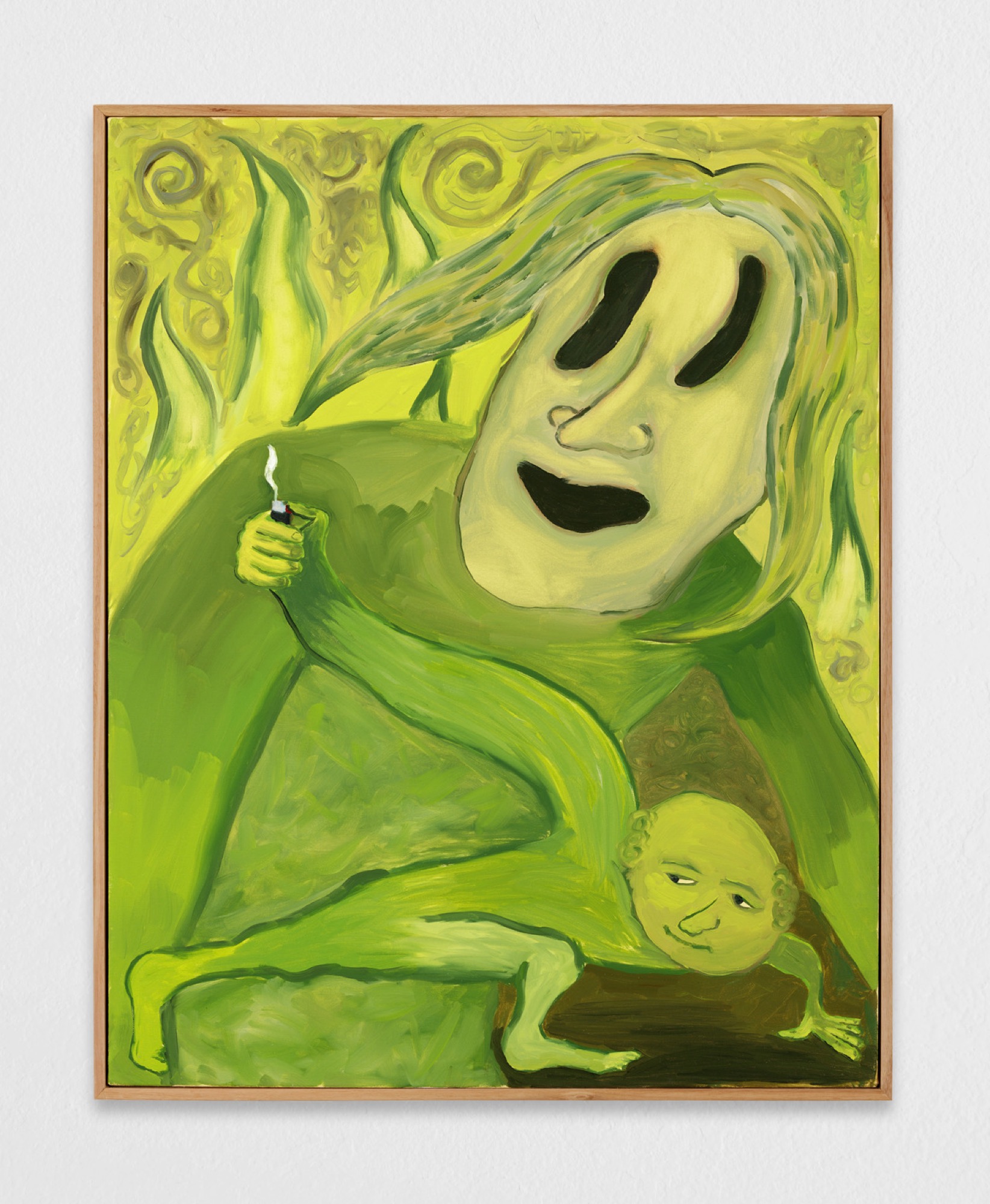

In Bitcoin Eating Daddy (2021), a ghoulish head with wobbly limbs rides on the supportive shoulders of a virile body recalling the geometric musculature and stoicism of social realist painting, such as Phillip Guston’s Gladiators (1940) or José Clemente Orozco’s Barricade (1931). Bitcoin’s open jaw is clamped to the chiselled head of “daddy”, while the benevolent superman-esque figure carries the babyish Bitcoin forward into an atmosphere of dropping diamonds. Presumably epitomising cryptocurrency, these shapes generate a sense of speed in the painting while Bitcoin’s clamped jaw suggests a kind of battery-charge given to “daddy”. In Fighting (2021), Seymour works in green—muddy, fluorescent, moss, forest, pea and turquoise—to create subtle deviations among the many interlacing limbs, mirroring fists and allegoric heads: an overall effect of organised chaos calling to mind M. C. Escher. Visually complex, the perspectival crescendo of suspended forms converge at the painting’s conceptual centre, where the eye is drawn to the superhuman face of a knife-wielding sun. Light bars radiate from behind its bearded skull and the sun god’s subdued expression tempers what is otherwise a climax between rippling fists and the many faces of Seymour’s seasons. While Fighting is one of the larger pieces approaching the consolidated palette of a Jutta Koether red painting, the Cologne artist’s influence can also be seen in such works as Looking Out of a Diamond Ring #1 (2021) and Bitcoin Showing Autism the Flame (2021). Sketched or stained in layers of boggy yellow and blue, these works produce the effect of a mystical prism containing jester, sun and ghost caricatures.

It is through these caricatures that one contemplates Autism, Bitcoin and the Four Seasons as a collection of portraits of the same person, or better still, a group of persons made up into a unique family. In an Instagram post for the exhibition, the artist describes “Autism” as the “main protagonist … represented as both male and female, human and animal, and is loosely based on Seymour, his ex-girlfriend and his best friend, who are also Autistic”. With this, Seymour proposes the “Autism” figure as both one and many. We are reminded that autism as a category, classification or diagnosis is based on a myriad of characteristics: each person’s manifestation of these markers or traits is unique.

If this collection of works invites us to question the experience of neurodivergence, another “spectrum” it presents is that of currency, both in terms of what is accepted or policed as the day’s discourse as zeitgeist as well as that of money. Creating normative values as it both includes and excludes, currency in all its forms shows us that a person can be either inside or outside of wealth just as much as they can be in or out of sync with the times. If autism is a spectrum, money is a spectre. And within the many margins of autism, we are also asked to comprehend the indigestible and haunting predicament of money. This value system is made even more arcane by the divergence of cryptocurrencies, which in their digital transition literally take the power of the sun. Digital currency in its transference of the sun’s power then becomes another value that one has or doesn’t have access to. We might then wonder if the Autism/Bitcoin correlation ultimately articulates the situation of being inside and outside, in that the prerequisite for social participation might ultimately require both money and a sound mind? Depictions of fighting, crying, killing, eating, sunbaking and watching YouTube all become scrutinised within this dichotomous puzzle, prompting us to ask if Seymour’s obsession with Bitcoin is analogous to the trope of the suffering artist.

Social realism historically depicts the working class, those people who are lacking in wealth but together wield almost mythical power. The artist in this context is both a hopeful conduit of this power but also a downtrodden outsider to capital. In a sense, the correlation of currency and difference—of power and punishment—gives Orozco’s and Guston’s works their internal logic. So how might we read Bitcoin’s clamped jaw or Seymour’s knife-carrying sun against the cultural context and utopianism of something like early twentieth-century American social realist painting? The payroll and weekly salary Guston received, for example, when producing murals for the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) as part of the New Deal certainly feels like mythology in today’s techno-capitalist economy. Though the suffering artist was most certainly not absent during the Great Depression, this trope is almost always followed by a couple of taboos: Guston suffered in reason after finding his father hanged. And while an obsession with money is unpalatable among certain circles and routine among others, being poor still somehow feels so … unmentionable. It seems that the relationship between difference and currency in Seymour’s works permits me to mention, at least to myself, the unmentionable.

Several works in this exhibition fixate on the act of looking, with up to five titles including the phrases “Looking in” or “Looking out”. In addition, “Autism” and “Bitcoin” are frequently presented in relation to the sun. Through these multiple configurations a pattern emerges whereby the gaze, like an electric current, is seen to be passed or exchanged like a baton or token between the allegorical figures. In Looking Through Summer’s Face (2021), the sun’s rust-coloured face takes up the entire picture, its little flames flicking around the edge of the painting like oiled hair. And, eating what looks like their daily gruel, a pallid little body sits between the sun’s piercing white eyes and reddened mouth. We attempt to stare at the skinny body sitting in place of the sun’s nose, but the sun’s eyes burn into us. In 10 to the 77 (2021), a broad-chested figure stares down at his freakishly enlarged fingers balancing the sharp edges of a silver star. We search for the blurry gaze of this washboard figure, but are instead met by the piercing little star so that we too become suspended by the mutilated fingers. Disfigured bodies with their gazes intact, these forms recall the blue-breasted alien in Don van Vliet’s Crepe and Black Lamps (1986), or the colourful distortions from René Magritte’s “vache period”, such as the terrifying clown in Le contenu pictural (1947). In bearing the reductive classification of “outsider artist”, Vliet who is lesser known for his paintings and most recognised as the musician Captain Beefheart, is someone delineated as the outside. These delineations seem to plague artists throughout history, to both generate forms of visibility or electricity, as well as deep long shortages—this is particularly true for women artists, who are most often written out of the “spectrum disorder” discussion as well as our art histories.

Seymour shares a designation with the “Autism” protagonist, which speaks to the mutability of this “disorder”: a collective transfiguration suggests that the neurological classification of living upon a “spectrum” is free flowing like the randomised activity of cryptocurrency. In this case, Seymour’s own Autism can be depicted through the autistic experiences of those close to him. And, like Bitcoin and also like painting in pure abstraction, a neurodivergence cannot be summarised; the randomised nature of such neurology is constantly evolving and thus unpredictable. Curiously, the two key actors in the show—Autism and Bitcoin—are animated into form outside of the paintings themselves. First, the asceticism of Neon Parc’s Brunswick exhibition space is modified to include a low-frequency experimental soundtrack embedded with Seymour’s own “stimming” sounds; the lighting has been reduced to an ambient glow, and the viewing numbers were restricted at the opening to seven at a time—a choice made by the artist not for social distancing, but for the sensory aversions of neurodiverse audiences. Second, Seymour is selling digital versions of each of the paintings as Non-fungible Tokens or NFTs. In an exhibition of the first paintings ever produced by this artist, the decision to financially circulate discrete versions of the works online contrasts with the obvious anachronism of a painting show with something as purely speculative and immaterial as code.

This prompts us to ask what it means for an artist to be working in the oldest medium—and for the first time—to then make his subject matter techno-economics, neurology and transformation? When critiquing the eradication of medium specificity in artist designations, Lizzie Newman points out how painting is one of the most basic attempts anyone can make in art. And then the painter who is also a writer writes, “painting is an attempt to ameliorate the effects of the techno-scientific languages upon us: to evade the new dominance of the writing of numbers and statistics that are used to administrate us”. Where NFTs are a priori abstracted as code, painting is concrete, bodily and physical. Like the soundtrack to the exhibition giving Seymour’s disfigured bodies a voice, the paintings both become code and also position the currency behind the code as something akin to the mind: complex, forging new pathways. While the new techno-administration presents yet another economic avenue through which the artist now navigates an already nebulous market, Seymour produces paintings that are both inside and outside of this dimension, new and old; they both exist in the real and they transmute into code.

Seymour’s new body of work presents a collection of images thematically speaking to the stages or seasons in an individual life, which when taken together depict the many layers of an interior world. Simply put, a “person type” is an oxymoron: the randomness of the individual is better described as a galaxy, phenomenon and constellation. While the sun is commonly held as the giver of life, Claude Lévi-Strauss records a pan-American dawn dance mythology between the forbidden lovers of the sun and moon, on whose ashen surface the sun’s flames blot an image of eyes and mouth. This image not only outlines the eternal dichotomy of light and shade, it also speaks to the innate transitions occurring within and between those two dimensions at all times. The sun as we know pulls along and measures the seasons, its charged face a torch for the day. But the moon, its so-called opposite bears that same sun’s fabled marks and is sometimes, ever so slightly, seen at day. If we borrow this tale of metamorphosis—of what feels like the subsequent eclipse of sun and moon, inside and outside, of having or not having—Seymour’s work invites us to give attention to these transitions, offering something less dichotomous so that the growth itself can be named.

Adelle Mills is an artist who writes and lives in Naarm.