Josef Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski: Solid Light

Jane Eckett

Why is Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski not more widely recognised as the post-war modernist pioneer he evidently was? His work was at the international vanguard in terms of his experiments with sound and light, with clear links to the Zero group in Germany and their wider international network of affiliated artists including the Gutai group in Japan and the Nouveaux Réalistes in France. It is rich enough to have sustained numerous scholarly studies, which claim him variously as Australia's first video artist, the first to use lasers in a stage production, an innovator in creative microcomputing, and not just the first artist to create electronically generated images in Australia but also one of only a tiny few to do so in the early 1960s anywhere in the world.

Yet for all that he is something of a cult figure among artists and scholars concerned with the intersection between art and technology. Ostoja-Kotkowski is far from a household name. No state or national gallery afforded him a survey during his lifetime and to date none have done so posthumously. Kudos is due to the McClelland Gallery for being the first to grant him this honour, twenty-five years after his death, and for producing a fine catalogue to accompany the exhibition.

This is a tightly curated exhibition that showcases some though not all of Ostoja-Kotkowski's multifaceted projects and ideas. It begins with a striking juxtaposition at the entrance to the exhibition. On the right is Theremin 72 (1972)—a wall-mounted stainless steel square panel, sandblasted with an op art design and attached by wires to a small theremin on a nearby shelf. As the unwitting visitor enters the exhibition and approaches the work an unearthly electronic wave of sound pulsates from the steel plate, mirroring in aural form the swelling and rippling lines etched on its surface. It instantly establishes Ostoja-Kotkowski's two main concerns: sound and light, while also creating an unexpected yet appropriate context for the exhibition in terms of experimental electronic music. Theremin 72 entered the McClelland collection in 1974—a prescient acquisition made under Carl Andrew's directorship—and provides the necessary pretext for the McClelland mounting this survey show.

Hanging on the opposite side of the entrance are five small black-and-white pen and ink drawings dating to 1950 or thereabouts, also from the McClelland collection (in this case purchased in 1991). These adhere to School of Paris expectations in their cubist reductions and use of a continuous line, recalling Surrealist experiments in automatism, and are likely a product of Ostoja-Kotkowski's art schooling at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, 1946-49, and his exposure to the flow of exhibitions mainly from France but also from Britain and Italy in the post-war years. While visually appealing, the drawings are youthful exercises that hold little promise of what would follow.

More research is needed to establish the the true legacy of Ostoja-Kotkowski's German art schooling. Zero founder Otto Piene, seven years Ostoja-Kotkowski's junior, was also in Düsseldorf in these years, and it seems likely the two were acquainted. Certainly there are many similarities in their choreographed performances employing lights and lasers and their close collaborations with scientists. At least one wall text in the McClelland survey mentions Piene in connection to Ostoja-Kotkowski's kinetic sculptures and cites Piene's call for a new medium that can 'transform the power of the sun' as a portent of Ostoja-Kotkowski's use of lasers. If the relationship between Ostoja-Kotkowski and Piene can be established, the perenial question of who influenced whom should perhaps be set aside in favour of questioning what factors in Düsseldorf precipitated both artists to pursue such closely parallel paths and why Piene should have received institutional support in Europe and the US where Ostoja-Kotkowski received neglect and often intense critical resistance in Australia.

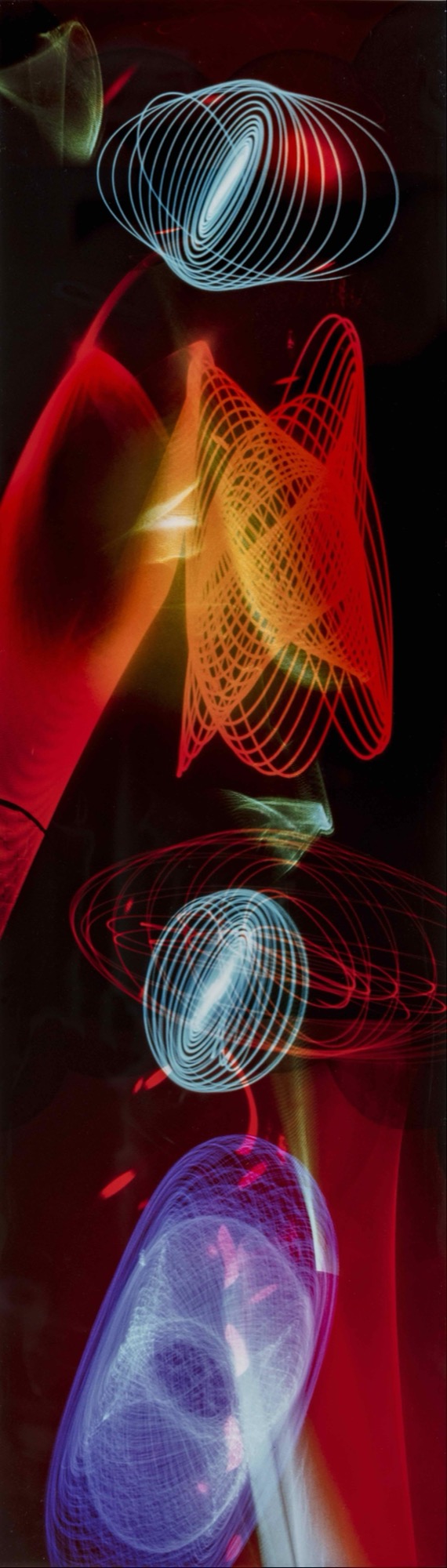

The main body of the exhibition is arranged by medium rather than any distinct chronology. The first room entered presents the visually arresting electronic images Ostoja-Kotkowski began making in 1962 by modifying a cathode ray television set so that he could control electron-beam deflection waveforms using audio waves. The elegant arabesque forms recall Constructivist sculptural forms, captured photographically. These are presented alongside some examples of his more diffuse Cymatics photographs that document sound waves and were developed during an ANU Fellowship in 1972, as well as the undated black and film Dream, in which dancer Judy Dick responds to Ostoja-Kotkowski's light and sound projections.

Dominating the second room is a series of five large Op art paintings from 1965-67, employing narrow strips of 3M tape collaged onto vividly contrasting backgrounds. The formal geometries and psychedelic colour schemes of these works seem entirely fitting with the hard-edge colour field abstraction that prevailed at the time; but a more specially Polish context is established through the inclusion nearby of two paper cut decorations, or wycinanki, and a wool kilim, all from the _Łowicz_region and dated c. 1965, which employ similarly vivid colours and mirror-symmetrical compositions. This folk art context is an intelligent rebuff to Elwyn Lynn's objection—cited on one of the wall texts—to the 'retinal' rather than 'emotional' appeal of the Op art paintings, suggesting Lynn overlooked the emotional content of foreign traditions.

Also in this second main room is a single example of Ostoja-Kotkowski's mid-1960s kinetic light boxes he termed Polachromatics. Effectively this is a small television-like construction with coloured cellulose forms arranged under glass. Behind them are fluroscent tubes and a motorised rotating disc that blocks off areas of light, thereby changing the colour of the cellulose forms. The motorised disc appeared not to be operating the day I visited, but the ties with other kinetic light works such as Frank Hinder's or the much earlier Farbenlichtspiele of Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack's were still evident.

Less evident was the link between the Polachromatic image (1966) and the series of slides projected at the far end of the gallery. The disarmingly quotidian subjects of the slides ranged from simple still life studies of candle flames and lamps to landscapes and skyscapes. According to the wall text the slides record Ostoja-Kotkowski's abiding concern with light 'as a medium and subject', and his experiments with colour filters, multiple exposures and lens flares. These experiments presumably fuelled the Polachromatics. The missing link is the series of experiments he began in 1955, sandwiching transparencies together to create abstract compositions from figurative photographs, which were the basis for his later sound and image performances.

The final room of the exhibition consists mainly of archival material and photographic documentation of his laser performances and theatre set designs, as well as a documentary interview with Ostoja-Kotkowski that conveys the sense of disbelief and suspicion prevailing in the sixties concerning art made with technological means. A black and white photograph depicts the artist dressed in sci-fi glamour beside his Laser-Chromoson (1972), developed in Canberra during his ANU Fellowship. This device consisted of a Perspex sphere containing two helium-neon lasers and six coloured lamps, attached to circuitry that translated sound from a microphone, synthesiser or tape-recorder into signals that controlled the strength of the light or vibrated mirrors to move the lasers. Other colour photographs capture later laser performances from the 1980s, while two black and white photographs record the 37.5 metre high Chromasonic Tower for the Adelaide Festival (1970) and the Laser Chromasonic Tower for Civic Square, Canberra (1975). The first of these towers was a vertical blade-like structure of 400 blue, red, yellow and white light bulbs controlled by an electronic system that responded to the frequency of recorded music. The second tower comprised a cylinder of large translucent panels onto which moving laser images were projected from inside the tower, controlled by sound. Both were major achievements in terms of scale and technical sophistication.

Lack of physical exhibition space seems to have been the main reason we see less of Ostoja-Kokowski's other public art projects and commissions. It would have been good to see photographs of his eleven-storey temporary light mosaic he created on the façade of the MLC building for the 1964 Adelaide Festival, his 18-metre-long bas-relief mural for Melbourne's BP House (1964), a similarly scaled mural for Adelaide Airport (1970), which has since been placed on long-term loan with Flinders University, or his vitreous enamel theremin mural for Melbourne University's McCoy Building (1975). And there are many more besides. Given the modernist commitment to interweave art and life, and to integrate art and architecture, it is a shame that this important aspect of Ostoja-Kotkowski's work remains largely invisible. Perhaps a second survey focusing on the public works is warranted? But coming in this year of the celebration of the centenary of Bauhaus and the arrival of some of its artists in Australia, it somehow seems appropriate that we similarly recognise Polish-born Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski and the contribution he made to the artistic life of this country.

Title image: Josef Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski, Nymphex, 1966, gelatin silver photograph from electronic image, 50.6 x 60.8 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, gift of Dr George Berger 1978. © Estate of J S Ostoja-Kotkowski. Photo: Christopher Snee, Art Gallery of New South Wales.)

Jane Eckett teaches art history at the University of Melbourne and was the 2018 Ursula Hoff Fellow.