Jordan Wolfson: Body Sculpture

Victoria Perin

In an interview from February 2023 with the National Gallery of Australia’s curator Russell Storer, Jordan Wolfson does a charming little dance. Storer (who has since quit his post as Head Curator of International Art after about 20 months in the role) wants to know, what “do you constantly ask yourself?” The forty-three-year-old New York-born artist riffs, “Is this good enough? Am I good enough? Did I do my best work? Am I avoiding my work or an idea out of fear? Am I still a good artist?” Still draws an important line across that last sentence. A fountain spurting neurosis reveals a confident monument beneath. The idea of a good artist is an archetype. The Good Artist is both confident and insecure. The Good Artist holds himself to account, checks in with himself constantly. Maybe he decides that he is still good, but he always knows that he can slip. This knowledge keeps him sharp: after being good for a while, you can be less good.

Cube was the working title of an artwork that Wolfson sold to the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) for $AUD6.67 million in 2019. When it was delivered in 2023 it was now renamed and repackaged as Body Sculpture (2023). In her withering 2020 New Yorker profile of the artist, Dana Goodyear gives readers the long back-story of this work and its acquisition. She sets our scene as the controversial artist pitches Cube to galleries and museums in North America and Europe. The literal punchline of the article? The work ends up in Canberra, Australia. It’s clear throughout the piece that Goodyear finds the artist painfully irritating:

“‘Cube can play the floor like an instrument,’ (Wolfson) said, pounding rat-a-tat-tat on the hood of my car. ‘Cube can play its own body like an instrument’—he patted his torso. ‘Cube can caress the floor.’ He smiled. ‘Cube can rape the floor,’ he said, holding my gaze—would I blanch?—as he put both hands down on the hood and mimed sex with my car.”

The NGA acquisition is Goodyear’s last laugh. The work lands in a kind of purgatory for the artist’s minor sins of being annoying and quote-unquote toxic.

So, we’ve been passed a grenade from the ivory towers of Contemporary Art discourse. Has it exploded in our faces? Is it a fizzer? Reading through the material around this work, Body Sculpture had been branded as a transition piece, one that has matured the eminently cancellable enfant terrible. In an interview in Interview with his zeitgeisty counterpart, the German artist Anne Imhof, Wolfson excitedly calls Body Sculpture “the third piece,” following his two most famous works, (Female figure) (2014) and Colored Sculpture (2016). All three artworks utilise a charged figure that performs for a small audience. Now that the trilogy is complete, we have an opportunity to stand back and assess the accomplishments of this youngish, major artist.

Except that very few people have probably seen all three works. (Female Figure) was debuted in New York by David Zwirner in 2014 and is now in the collection of the Broad Museum in Los Angeles. Colored Sculpture was first shown in New York by David Zwirner and has been acquired by the Tate Modern in London. Both works have toured, including a showing together at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Body Sculpture hasn’t been shown anywhere but Canberra. On my seven-hour drive there from Melbourne, I wonder exactly how many people have seen the trilogy in person. A vanishingly small amount, I imagine. Body Sculpture is the only work by Wolfson I’ve seen (I know that his curatorial supporters probably want me to say “experienced”) live. Before I go to Canberra, I’d encountered Wolfson the same way most people have: through hair-raising viral clips of the first two sculptures in the trilogy.

The lack of context for Wolfson’s work is affecting Body Sculpture’s reception here. Before Body Sculpture arrived, the Australian press submitted some very chatty notices about its purported themes, Wolfson’s reputation, the work’s relatively big price-tag. After it arrived? A strange hush has washed over local critics, with very few developed opinions being offered in either the positive or the negative. The NGA reassures us that Wolfson is an important artist, but we’ve never met this guy. Modesty prevents us from gossiping publicly about our visitor. In private, however? We’ll get to that…

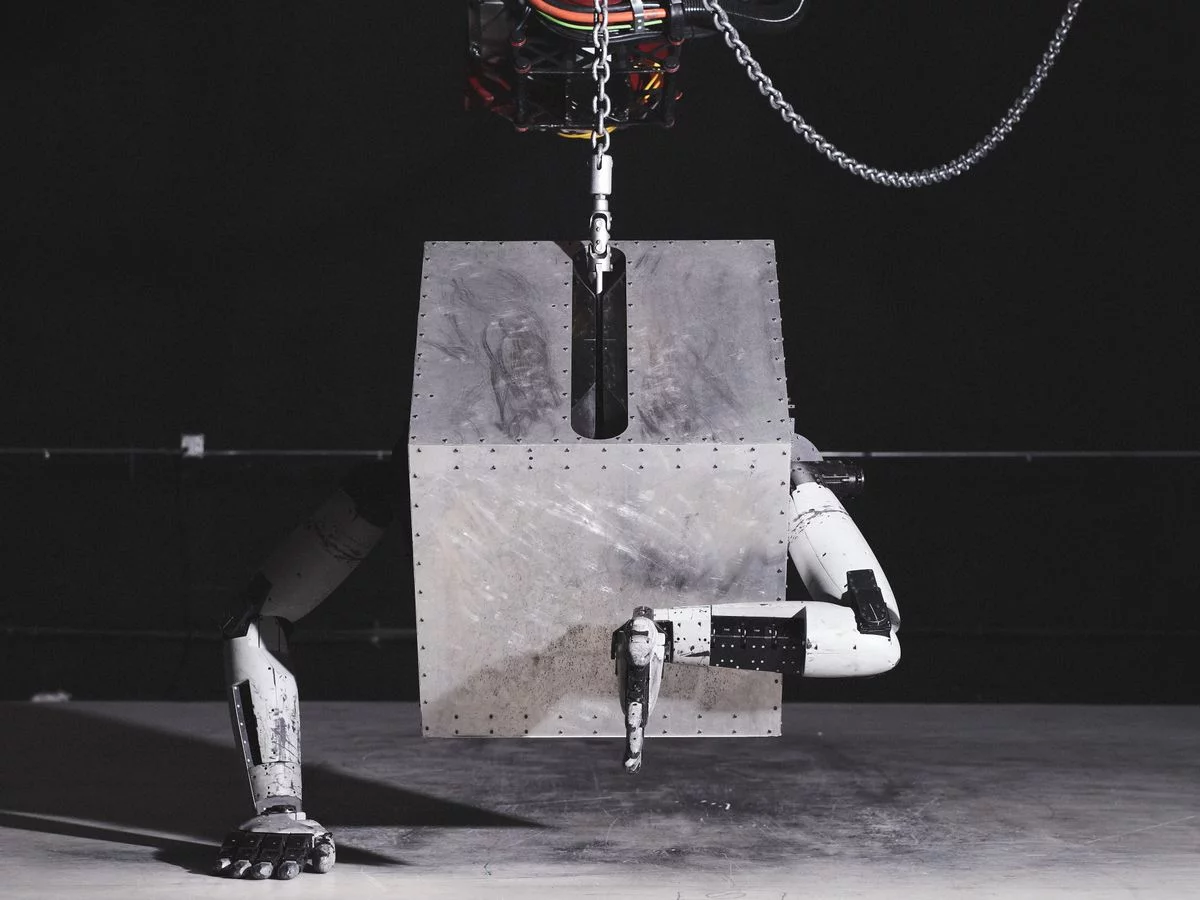

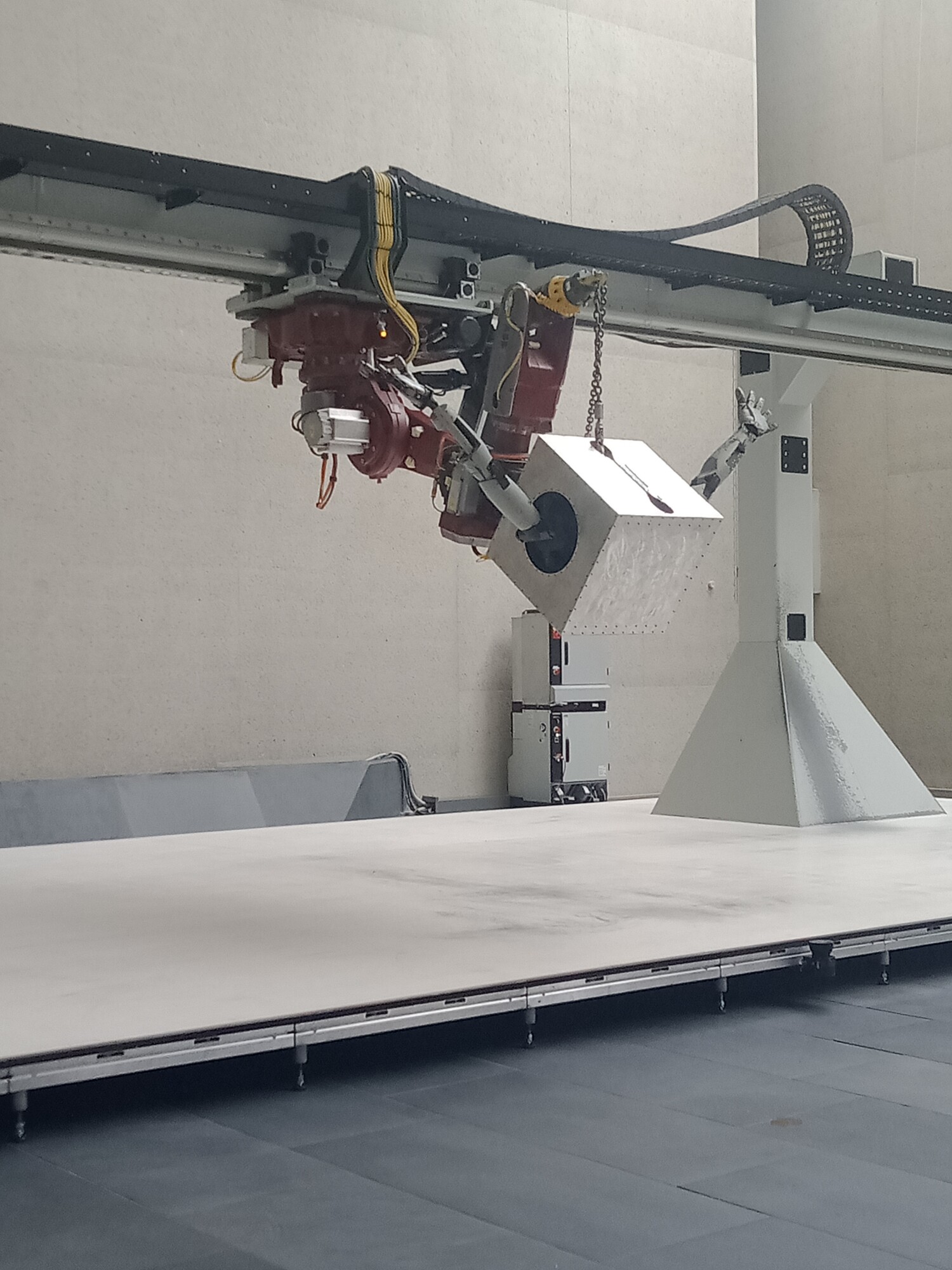

The trilogy repeats certain core elements, creating a through-line beyond the robotic conceit. (Female Figure) is a stripper-witch animatronic with a great body and a terrifying face. It dances seductively up and down in front of a mirror, talks cryptically in Wolfson’s voice and is accompanied by pop song playback. Equipped with facial recognition technology, it looks audience members in the eye. Colored Sculpture is an animatronic puppet that also looks audience members in the eye while it talks cryptically in Wolfson’s voice. The puppet has articulated limbs that are strung up on chains, and it is flung violently around a stage accompanied by Percy Sledge’s sentimental hit When a Man Loves a Woman (1966). Also strung up on a chain is Body Sculpture, a grey metal cube with articulated arms and hands that have amazing dexterity. The cube’s chain is held by a robotic gripper that moves it around a stage. The cube makes its own percussive music, by tapping and slapping itself. It has a “face,” in that it has a front side that never turns from the audience, but it doesn’t look anyone in the eye, and it does not speak.

The early videos of Body Sculpture never seemed to hit the peaks of virality that Wolfson’s other works used to. You could do the numbers (I’m sure someone at David Zwirner is hired to do the numbers), but anecdotally the algorithm has never offered me a video of Body Sculpture that I haven’t gone looking for. The virality of the first two works, and the reduced virality of Body Sculpture, could be a good or a bad sign. Has Wolfson lost his touch? (Am I still a good artist?) Or is this a sign that he has grown tired of an artistic formula designed to provoke online views? Wolfson’s charmed history with social media should have protected him from Canberra’s isolation, broadcasting his work to his fans and critics across the world.

Wolfson and his gallery representatives didn’t exhibit any public concern about Canberra’s remote location, but small signs suggested that they did in fact see it as a liability. The first slip that distinguishes the concept of the Cube from the reality of Body Sculpture was the quiet admission, made public around the launch, that the NGA’s new acquisition was number one in an edition of three, with two additional artist’s proofs. Apart from raising the value of this $AUD6.67 million artwork to a figure potentially five times that, this repositioning of Body Sculpture does away with the problem of Canberra. The work won’t be permanently stashed away in one of Australia’s smaller cities, a location that is evidently too far to even spin marketing about a “pilgrimage piece.” There will be other versions, and if all goes well for the artist, they’ll probably be planted equidistantly around the globe.

Maybe by the time Wolfson and his subcontractors make the new editions, they’ll have fixed the operational problems that the NGA’s one is having. Accounts of Body Sculpture’s breaking down abound. I spoke with one artist who was greatly enjoying the work, when, around the 23-minute mark, the roughly 30-minute performance abruptly halted. The audience was ushered out of the gallery while regretful invigilators noted that this had happened before. Gossip around the Canberra scene suggests that this has continued to happen. I wasn’t surprised to hear these rumours—during my own visit in December 2023, a black screw popped out of the work as it vigorously beat its metal chest. Did you see the cube? We ask visitors returning from Canberra. Was it working?

Undoubtedly, it would be very disappointing for tourists who have travelled far to see an interrupted performance. Personally, I think technical difficulties are an important part of the disappointment of robotics, and proof that, for all their purported sophistication, it’s still a mammoth effort to make a robot stack shelves in a warehouse, let alone dance with elegance.

But the Body Sculpture breakdowns are more important for showing how Wolfson relies on certain tropes across his trilogy. Wear-and-tear is part of the artist’s robotic aesthetic. (Female Figure) is scuffed and charred for appearances. The abrasions perfectly match her Halloween appeal. The costume of violence was transformed into real violence in Colored Sculpture, which is bruised and grazed as a result of its aggressive functions. Staff at the Tate Modern have confirmed that parts of Colored Sculpture need to be replaced constantly, and, like the Ship of Theseus, the whole work may essentially be remade after “1 or 2 display cycles.” The NGA had to be fully aware of the unprecedented and ongoing costs of exhibiting and maintaining an artwork with this kind of material and technological extravagance.

Like Coloured Sculpture, the cube is heavily worn. The floor carries the scuffs of its path across the stage, and paint on the gantry is worn from a key moment in the performance where the gripper flogs its supporting beams with chains. I don’t expect this work to stay shiny like a new Tesla (it can get rusty like a new Cybertruck, for all I care). But it is clear that what started as a rough-and-ready style in (Female Figure) has evolved to be a major, and not uncomplicated, aspect of Wolfson’s oeuvre. Grit started off as a bit of faux-texture on a sexy outfit, but now we are left with a robot that dies and needs to be tended to constantly. What should we make of this escalation from a grungy aesthetic to a busted reality?

But what about when the work does rally, and completes its full performance? The Body Sculpture starts with an act of drawn-out poses that the artist persuasively describes as a “sculpture garden.” In one of the few reviews of Body Sculpture, Wes Hill praised the work’s “capacity to slow the room down to its own methodical yet unpredictable tempo.” During my visit, this hypnotising effect does not occur for me. The performance is slow. While its fingers, hands, and arms occasionally move very quickly, the cube rarely does. This gives the viewer a lot of time (I’d argue much too much time) to anticipate what might come next.

I note that the cube appears too delicate to be dropped heavily on the ground, as in Colored Sculpture. It is dragged, and at one moment, it flies quickly through the air, but mostly it is suspended gently, or it is placed reverently on the stage floor. As its caretaker, the gripper treats the cube as a fragile object. But when this responsibility overwhelms the gripper, and its pent-up energy is expended by whipping the gantry with chains, I can’t help but feel a little misdirected. The cube can’t undergo such violence, so to incorporate this shock the action must move away from the protagonist. In its apparently delicacy, I start to think of the robotic engineers who made the cube, and the limits placed on the artist by the medium. In other words, I start to think—mid-performance—about the work’s technical limitations.

Contrast this with the visceral reactions that audiences of (Female Figure) and Colored Sculpture have reported. I’m thinking of Mark Godfrey, Senior Curator at Tate Modern, who told Goodyear that he “lost control” of his “critical faculties and gasped out loud,” when he first saw Colored Sculpture. I’m also thinking of a great anecdote Wolfson gave, when he describes (Female Figure) suddenly looking at him in the eye late one night during its development, causing him to scream and flee the building.

The second slippage between the Cube and Body Sculpture—one that has major implications for the work—was the removal of any interactive element. Eye-contact, mediated by facial recognition software, such a vivid element to the first two animatronic works, was never a part of Cube. Faceless and eyeless, Cube was instead supposed to point. And (as spruiked by NGA Director Nick Mitzevich in the New Yorker piece) it was going to point specifically at the viewer’s genitals! In lieu of using facial recognition to yoke the performer and viewer together, Body Sculpture unpacks itself as a choreographed dance, repeating the same moves at exactly the same beats in exactly the same places in every performance. When it sweetly beckons to the audience, with its extraordinary fingers, it beckons to no one in particular. It’s a momentous change in the trilogy, and a change that seems to affect the earlier works as well and the new one.

Despite the fact that Wolfson has marked this shift repeatedly in his public commentary, even sympathetic interviewers got confused. “The work literally points someone out, doesn’t it?” the art writer and NGA Council board member Alison Kubler asked in her Vault interview. “Actually, it doesn’t do that anymore,” Wolfson responds. He continues:

I took that out, but that wasn’t something that I could anticipate being negative. I anticipated it being generative and then it was subtractive. It felt sticky and bad and blah. It was one of those funny moments where you toss out an idea you’ve been committed to for five years in five minutes because you just see it finally come together for the first time and it falls flat. I did get it to work in one way, but it ultimately wasn’t technically possible, so I made do and dropped it.

I try to follow the logic of what Wolfson is reporting here: Theoretically, the pointing was a good idea, but in reality it was lame. I impulsively abandoned it. I could do it (sort of), but it was also not possible to do. “I hate interactivity,” he might say at one turn to Anne Imhof, before explaining that, actually, he does covet interactivity he just subscribes to a more confusing model of it, citing Marshall McLuhan’s theory of “hot and cool” media: “the radio is a cold medium, because there’s just one voice speaking and you can never speak back to the radio. I want my interactivity to be cold.” (McLuhan famously describes the radio as a “hot” media). Wolfson’s conflicted statements about the work’s non-interactivity read a lot like self-soothing.

Storer is confident that Body Sculpture’s move away from this interactivity represents a positive development for Wolfson. In his canny catalogue essay, which mounts possibly the most rousing defence that could be made for the artwork, the curator writes that Body Sculpture “lacks the scrutable factors those other works share. Gone are the cartoonish faces, the haiku-like voiceovers and pop-music soundtracks, components carried through from Wolfson’s (earlier) animated video works.” Scrutable is the perfect word here. Storer’s implication is that Wolfson is maturing away from something that we can identify and process as meaningful towards increasing inscrutability and mystification.

But Wolfson puts it more simply: “I try to just do the idea, rather than know it or dissect it. I find that that’s not productive for me. This isn’t an intellectual practice.” As he articulates constantly to interviewers, intuition is Wolfson’s methodology. He might flit between mystification and meaning, like a butterfly going from flower to flower, but it is the lightness of his touch that he trusts, not the nectar.

What does that mean in light of his extremely labour-intensive animatronics? How do you flit intuitively around millions of dollars of tech? Wolfson and Mark Setrakian, robotics celebrity and Wolfson’s chief collaborator, have described their process at length. In the case of Body Sculpture, Setrakian prepared a myriad of movements and gestures for the cube, and Wolfson would visit and select the moments that spoke to him. As he puts it, “a light would turn on in my body.” Setrakian would then work out a sequence based on their shared goals for the artwork.

Wolfson’s focus on intuition in art is bolted onto his sincere devotion to meditation, which he talks about constantly, and affirmation journalling. Like other people who are drawn to clearing their mind of negativity, pain, and intellectualising judgements, he’s a moralist about non-morality. Despite claiming that “Body Sculpture is an artwork without a moral position,” he observes to Storer that “most people at most times are not present in their minds or bodies, they are elsewhere distracted by anxiety, confusion, desires, etc.” Is Body Sculpture a response to this predicament, maybe even a temporary reprieve? “The intention is that the movement of the sculpture elicits the viewer to become activated in their bodies and therefore present.” Welcome to class, find a space where you feel comfortable. We’ll begin with a deep breath.

I understand Body Sculpture’s process of subtraction as a kind of cleansing. Gone are the alarming faces, the coy voiceovers, the internet-scroll pacing, and the pop-cultural, world-responsive references (which, I’ll just note, were previously considered Wolfson’s signature touches of contemporary camp). The attention-seeking elements were too attached to worldly distractions like “anxiety, confusion, desires, etc.” Wolfson was seeking something more cosmic: something he describes as a “frequency.” What animates the shell of this new work? Techne and vibes. The former is courtesy of Setrakian’s professional practice, the later courtesy of a watered-down, Westernised parsing of meditation, which teaches that being in touch with your body is superior to intellectualisation of any kind.

What Wolfson and Setrakian have created is an overbaked memorial to their lopsided process, with its competing values of spontaneous feeling mediated by indirect, painstaking technical refinement. Body Sculpture’s run time is too long. The tension that it creates is consistently undermined. For me this was encapsulated at the end of the choreography, when the cube mimes the gun-to-the-head suicide gesture, not once, not twice, but three times. At this moment, and others, such as the gesture of “becoming self-aware” when the cube gazes at its own hands, the gravitas intended is bedevilled by a disengaging ponderousness. As Wolfson puts it: “Mark … added the hand that moved with the trigger (gesture). And it became immensely sad. And the slower it was the sadder it was.” In its melodramatic logic, the performance is long because of its emotional profundity, and it is repetitive because things that are profound need to be underlined. It’s an underwhelming and patronising experience.

I was excited to see Body Sculpture. I could damn it with faint praise, and say I liked bits of the performance; there is a great sequence when the robot’s left hand performs an unhuman dance that is as exciting as it is elegant. But, then again, some of the bits were bound to be good. Making Body Sculpture’s entire performance remarkable, without the cool interactivity and the scrutable factors of his first two animatronics, was Wolfson’s real challenge.

With his worry-wart persona, I know that Wolfson has imagined the worse-case scenario: you are not feeling present during Body Sculpture’s performance. In fact, you are a little bored. You look over at a twelve-year-old (forced to sit on a fold-out chair in case he is overcome with spontaneous mischief). He looks bored too—this is unbelievable, as he is most certainly in the presence of the most unique robot that he has ever come across (and he is a twelve-year-old boy!). Hoping that the kid will have some sort of earthshattering experience at the gallery, for his sake, you start to will the cube to do something a little drastic. You wish, despite yourself, that it would pull some mischief out of itself. C’mon, I think, just point at my genitals a bit? It fucks the floor, as promised. Nope, that’s not it. Soon after you realise that you are bored, you realise that you might have fallen for some pretty cheap tricks in (Female Figure) and Colored Sculpture. Look at my eyes? Point at my genitals? Have we been duped by a little crowd work, the crutch beloved by all lacklustre comedians? No wonder Wolfson is trying to distance himself, however weakly, from the concept of the “interactive artwork.”

Ultimately, the NGA has bet a lot on this work. They’ve bet that it will translate to a context far from the trumped-up stakes of Biennale Art, that it will be a contemporary jewel in the crown of the gallery’s beautiful, brutalist architecture. But most of all, they’ve bet that Wolfson is at his peak. They leapt into the animatronic arms of the Cube before the development process was complete. Future research on this work and its acquisition will have the final say, but it’s hard not to conclude that Body Sculpture was under-conceptualised and overengineered. The light touch that Wolfson desired was challenged by the complexity and obfuscation of a long, six-year technical development that straddled the pandemic. Wolfson’s hazy intuitions about universal gestures can’t replace all that he stripped from his art, which was everything we liked about it in the first place.

Tell the world, reporting live from the scene in Canberra: Body Sculpture’s not the artist’s best. Lucky for Wolfson, though, Canberra has a lot of time for underdog artworks. In discussion of the acquisition, there is plenty of talk about Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles (1952), or the plethora of good bets made by the NGA’s inaugural Director James Mollison. Yet when the NGA acquires duds, even expensive ones like David Hockney’s A Bigger Grand Canyon (1998)—acquired under Brian Kennedy in 1999 for $AUD5.3 million—we will politely keep it around. We hang it over the escalator and forget it’s there. We barely ever mention it. But when we do, we might say something kind like, well, it’s not his best. But he is a good artist.

Victoria Perin recently completed a PhD at the University of Melbourne.