Jonathan Walker: Capturing Details Usually Screened

Jarrod Zlatic

No one that I mentioned the Jonathan Walker retrospective to had heard of Jonathan Walker. Before visiting Capturing Details Usually Screened, neither had I. The only people who did know of Walker had either met him directly or knew people who had known him. Walker’s relative obscurity is heightened by the exhibition’s location—Bayside Gallery in Brighton. The setting is appropriate because Walker lived most of his life in neighbouring Hampton. Critically though, the distant location (I am writing here from the perspective of a lifelong Northern suburbs habitué) maintains Walker’s peripheral relationship towards the Australian art world.

While Walker did have early to mid–career success, regularly exhibiting with the iconic Pinacotheca gallery from 1985 to 1992, and garnering high profile support from The Age’s art critic Gary Catalano, his profile waned considerably during the 1990s. Walker became instead something of a painter’s painter, remaining intergenerationally connected to the art world through his former painting students from Western TAFE, such as Lane Cormick, Lisa Radford, Amanda Marburg, Blair Trethowan, and Colleen Ahern. More incognito than impresario, his preference was to sit at home in suburban Hampton and read books, listen to music and occasionally paint.

That Walker is even the subject of a retrospective is bittersweet. It doubles as something of a memorial, following the artist’s sudden passing in 2020. Capturing Details Usually Screened is the second exhibition dedicated to Walker that Ry Haskings has curated. The first was staged at Haskings’s Fitzroy gallery Conners Conners and traced a lyrical thread of soft abstraction throughout Walker’s oeuvre. For the current show, Haskings has opted for a more straightforward approach, providing a solid overview of the distinct periods of Walker’s painting practice. Looking at all these works together demonstrates that while Walker’s practice did go through a few significant shifts over time, there were a few constants: a disinclination towards hard lines, patterning and definite forms, pictorial language united by uncentered arrangements, curving and indistinct shapes, and a tonalist approach to colours that often bleed and blur together.

Walker began as a figurative painter in the late 1970s. His earliest subjects were liminal spaces, initially domestic (doorways and windows) and then natural (rivers and oceans). The show opens as Walker’s decade of exhibiting at commercial galleries was commencing. The earliest paintings included in the show are from 1983 and 1984, just as Walker was dissolving his somber, atmospheric waterscapes into abstractions of pure atmosphere. There is a bottomless quality to Untitled No. 1 (1983) (nearly all of Walker’s works are untitled): the rippled surface of a river is crammed into the very top of the frame, while subtle, swirling shades of submerged Yarra-brown fill the canvas.

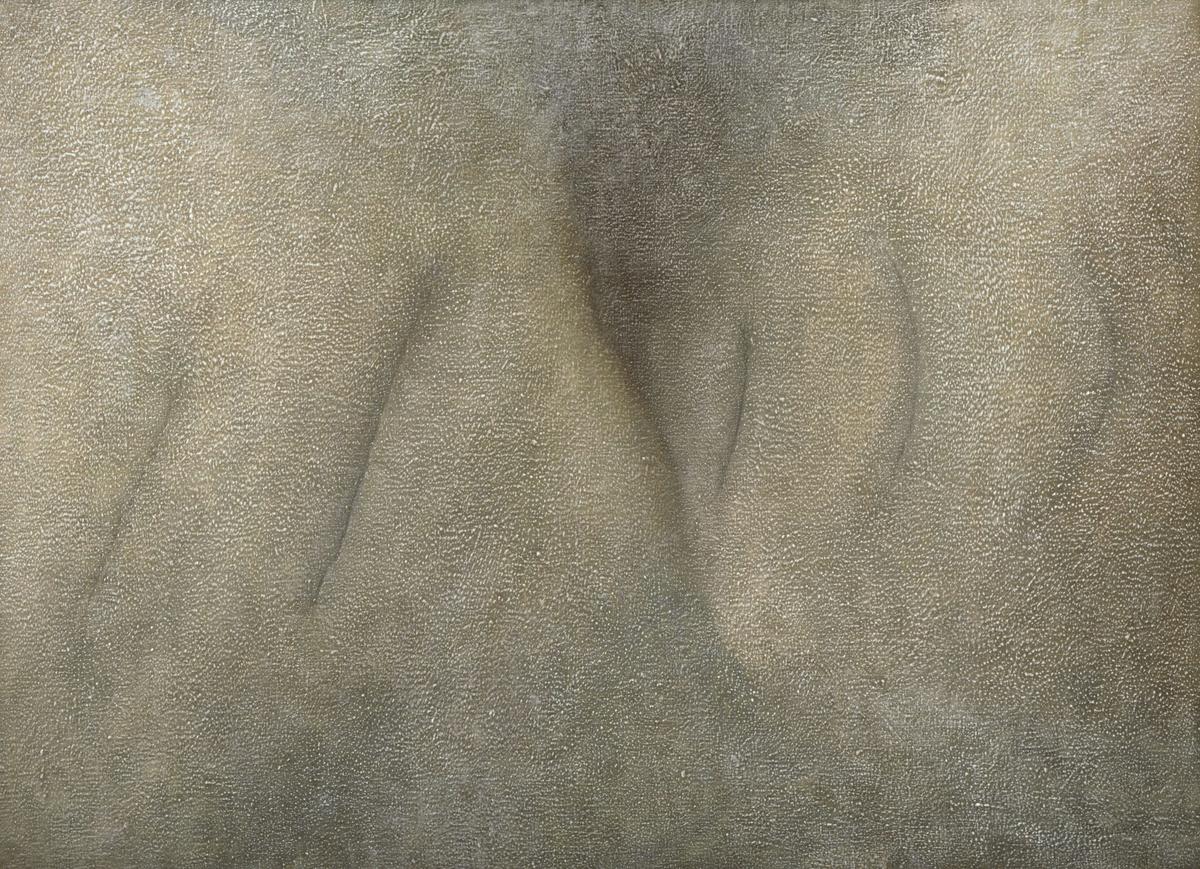

The abstractions of the late 1980s continue with this evocation of natural subject matter. Their biomorphic shapes and textures are suggestive equally of caves, tree trunks and human skin. This indeterminate quality is further underscored by the surface texture where the paint, which is usually applied quite thinly, congeals into spreads of sticky caramel. Untitled (1986), lent from Heide’s collection (the two paintings of Walker’s in public collections have been included here, everything else comes from what remained in Walker’s possession at his death), extends upon this textural element. Here Walker has mixed some type of foreign material in with the paint so that tiny stalactite-like formations ripple across the painting’s surface—a flesh-like expanse of waxy goose-pimples.

There is an ugliness to the abstract works. The palette is difficult—dim, grimy browns, greys and oxidised-avocado yellow—and the tonalist approach offers little in the way of relief. Given Walker’s interest in contemporary industrial music (more on that later), it is tempting to see these paintings as oblique riffs on the corruption of nature and ecological disaster. There are parallels between the decidedly non-pastoral anti-ambience of say Maurizio Bianchi and Walker’s perversion of the sublime. His expansive zones of space are suggestive of inhabitability, filled with what could be mud, poisoned water and choking smog.

To insist on such a deterministic reading of these works, however, would be a mistake. Walker’s paintings are, ultimately, insular. Despite the elemental qualities within the pictures they operate on their own inner logic, with little reference to the outside world as such. In the catalogue Haskings notes that there is a private, symbolist vein running through Walker’s work during the 1980s. There is an obstinate silence in these paintings that is at odds with how Australian painting of the 1980s is often framed. We see neither the self-declarations of the neo-expressionist artist nor the cynical commentary of the postmodernists (categorically speaking, Walker probably falls within the stream of painting that critic Charles Green termed “visionary abstraction”). Although Walker’s writings on music from the period demonstrate a familiarity with the 1980s French post-structuralism, his art avoids any handwringing about the death of painting and retains a dedication to the painter’s craft.

For Walker the 1990s were focused exclusively on his series of Spectral Paintings. These works bridge his changing fortunes as an exhibiting artist moving towards greater obscurity. The earliest Spectral Paintings are from his last commercial gallery show in 1992 (insofar as Bruce Pollard’s hands-off approach at Pinacotheca could be described as “commercial”) while the later works were shown at sporadic exhibitions in the artist-run spaces associated with his former-students such as TCB and Westspace. Indeed, Walker is a reminder that the common framing of ARIs as “incubator” spaces ignores that they increasingly provide a platform for mid and later–career artists who are without the patronage provided by commercial representation.

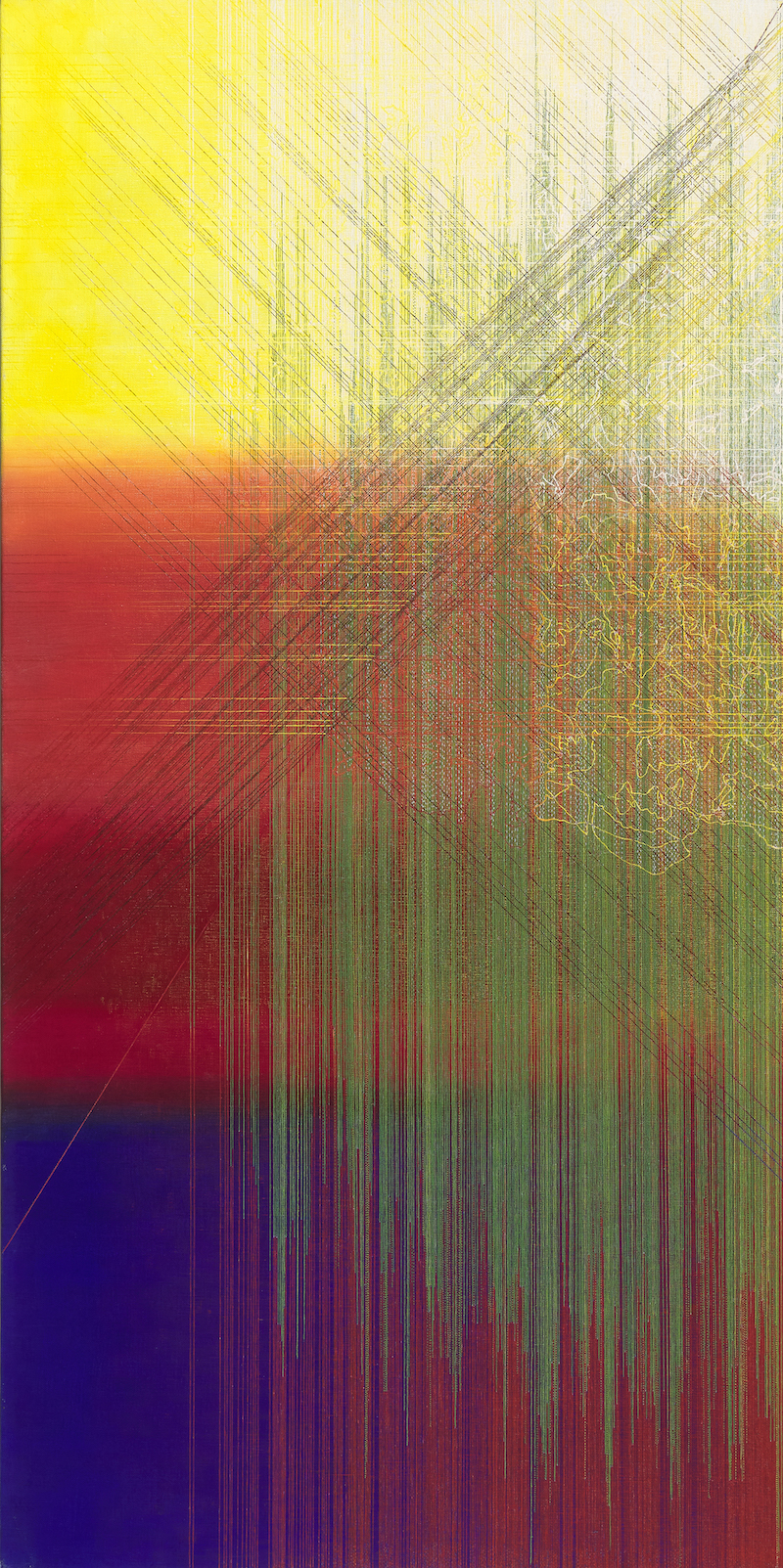

There is a basic framework for this series: vivid, glowing gradients of primary colours criss-crossed with masses of thin, straight lines that shoot across the canvas at all angles, overlaying the detailed outline of a lavender bush. They are composed with severely unromantic rationality. A complex mathematical formula, derived from Romanian composer Horațiu Rădulescu’s theory of Spectral Music, provides the determinations of their individual arrangements. The earliest iterations of the series have superficial correlations with the more eccentric end of modernist painting. The throbbing centres of colour and round, glowing gradients in these works are reminiscent of early twentieth century spiritualism-infused abstractions. The latter works are especially distinct, like a 2000s trance festival poster as seen through a broken LCD monitor.

From afar, these works look like screen-prints. Indeed, Walker studied and then taught print-making at RMIT in the early 1970s, winning a scholarship to study old master etchings in London in 1974. Up close, however, the works reveal a painstaking, meticulous attention to detail, and they begin to imitate textiles in how the fines lines and dots cross the textured surface of the linen canvas. This combination of subtle tonal shifts and high level detail means that these paintings suffer significantly in photographic reproductions in both the catalogue and the gallery’s website. Even in person the tonal overlays cause the paintings to resemble lossy, low bit-rate image files, as if the colour detail has become pixelated and lost.

The paintings from the Spectral Paintings series operate in stark contrast to the rest of the exhibition in their embrace of hard geometry and a palpable sense of “design”, otherwise absent from Walker’s pictorial repertoire. They are Walker’s painterly equivalent of the move from vinyl to CD. Yet they do still share the sense of endless, empty space that had occupied Walker throughout the 1980s—the nothingness of desolation found in the earlier works being replaced by the nothingness of digital infinity.

The 2000s mark the end of Walker’s era of large-scale paintings, the average size reduced down from meters to centimeters. The reduction in size is accompanied by a reduction in scope—what was immediately at hand in Walker’s home became the basis for his paintings. A series of works from the mid-2010s (some originally exhibited at World Food Books in 2016, his first show in a decade), utilise the reflections of his kitchen sink as the basis for a series of impressive quasi-abstractions. While seemingly casual, if not accidental, these works are the result of a patient choreography, with Walker placing himself and his kitchenware in precise configurations like an acrobatic Giorgio Morandi. As one working note for a painting in the series reads: “kettle on radio. I stand eighteen inches from cupboard corner legs akimbo. Experiment with door position. ALWAYS WILL NEED TO WEAR WINTER SHIRT BLUE + OCHRE SMALL CHECK PATTERN.” The chrome reflections render these arrangements as indistinct, curving, soft-focus distortions of blue, jade green and grey that are shot through with streaks of white, lavender, and pink. The patches of colour are gaseous, floating, and bleeding together in a way that feels fresh and unlaboured in comparison to the heaviness of his earlier work. Here, after the detour of the Spectral series, there is a re-engagement with the sublime in these miniatures of seemingly fathomless, icy spaces. Though being conjured from the most mundane of domestic items the sublime here feels more ironic than in the seriousness of the 1980s paintings.

The final series of paintings that Walker was working on prior to his death are collage-based. Pictures torn from the local seniors newspaper provide the raw material for haphazard compositions. Recognisable fragments reveal themselves: a pillow, a couple lunching at a table, a courtyard garden, trees, a post, a graveyard, glowing sunsets, a cricketer, gondolas on the water. But their arrangements are off-kilter, vying with jagged stripes of abstract colour and empty patches of linen canvas. There is a wryness to these paintings, with Walker re-purposing images of the seniors lifestyle (I’m guessing some of the source images in these paintings were originally ads for European getaways) into material for his own obscure retirement activities.

The approach to figuration in this series is as loose and restless as the pictorial arrangements. Each painting feels compressed—the paint is delicately daubed, flickered, clumped, and smeared in a way that vibrates with contained energy. The canniest painterly trick is Walker’s imitation of collage, so that the paint looks like it was glued on. The paint mimics the torn and frayed ends of ripped newspaper in a trompe l’oeil fashion, accentuated by patches of empty linen canvas.

Music, as much as painting, was a determining passion and influence for Walker. During the 1980s he remained more in contact with musicians then he did with the local painting scene. From his base in Hampton he kept up mail correspondence with many iconic figures within the submerged world of the industrial cassette scene, including Gary Mundy who ran the Broken Flag label in England, Maurizio Bianchi and Giancarlo Toniutti in Italy, and Masami Akita (Merzbow) in Japan. This correspondence was fruitful. One of Walker’s ambiguous animal/mineral abstractions became the cover of Giancarlo Toniutti’s 1986 LP Epigènesi. Walker’s contact with Merzbow led to an essay that accompanied a Merzbow album, and an article by Walker on noise and collage that focused on Merzbow’s pornographic collage works was published in Art + Australia’s bicentennial issue in 1988.

The most fruitful correspondence Walker participated in was with the German multi-media artist Achim Wollscheid. Wollscheid was a member of the Frankfurt-based artist collective Selektion and made concrete-noise as SBOTHI (Swimming Behaviour of the Human Infant). The duo’s correspondence developed into an artistic collaboration. Walker produced drawings that were immediate, improvised responses to Wollscheid’s sound works. Wollscheid would then photocopy, cut up and re-arrange the drawings into new works, which Walker then used as the basis for a series of paintings exhibited at Pinacotheca in 1989. These paintings appear as some of the more striking and refined products of mail art in Australia. They are unlike the usual inelegant or ephemeral works typical of the movement’s democratic immediateness. It is regrettable that they’re not included in the current exhibition, especially as they mark a significant shift in Walker’s approach to picture making (presumably their absence here has to do with the limits of the gallery, which is only made up of three hanging spaces). In the Wollscheid works, Walker moved from an imaginative basis for picture making, as seen in the 1980s nature-themed works, to the process-driven methods of his subsequent Spectral Paintings and 2000s domestic works.

The collaboration with Wollscheid also shifted Walker’s art beyond the strict confines of contemporary painting, towards the fringe areas of Australian art history. While Walker was not strictly speaking a mail-artist, the industrial cassette network he was part of was a direct outgrowth of the mail art movement. The Wollscheid paintings exist in a zone similar to that occupied by Pat and Richard Larter, whose paintings were also interspersed with their mail art activities. Walker also enters into another obscure non-tradition of internationally orientated multi-media collaborations grounded in experimental music. This tradition continues today in Christopher LG Hill’s recent sound-work contributions to the group show Track, Dash, Stroke at Tokyo’s Goya Curtain: sound-sculptures that were combined with live improvised accompaniment at the opening and closing of the exhibition. It can also be glimpsed backwards in the sound works included in the Outback Postal Art Show at the Orana Mall in Dubbo in 1980; Bruce Clarke’s activities in the 1960s (see his faint connection with Canadian concrete poetry and sound group See + Hear in 1969 and his involvement in the staging of Texan composer David Reck’s controversial multimedia work Blues and Screamer in Melbourne in 1968); the publishing of Harry Hooton’s prophetic essay “Jazz and Mechanisation” in San Francisco’s beat-adjacent journal Inferno in the 1950s; or Jack Ellitt’s pioneering sound collages for Len Lye’s films in 1930s London (which pre-dated musique concrete by a decade).

Capturing details usually screened is a fitting title for this exhibition, as Walker’s practice is an entry point to several aspects of art making often screened out of Australian art history. Though, of course, the title also refers to Walker himself, a detail that became unmoored from larger art narratives and institutions. And some might say that Walker’s hermetic self-isolation in Hampton was a more dignified alternative to a life in an Australian art-world that increasingly resembled one of his bleak 1980s paintings. The current exhibition is a welcome reminder of artistic traditions that continue to be maintained, despite the lack of critical, institutional, or commercial recognition.

Jarrod Zlatic is a writer and musician from Melbourne.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of MERIDIAN SCULPTURE.