Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley: Temptation to Co-exist

Francis Plagne

It is a somewhat disconcerting experience setting out to review an exhibition when one has the distinct feeling that whatever might be said about it has already occurred to the artists and is already, in some sense, factored into the work itself. This is precisely the feeling one has moving through this well-curated retrospective of the work of Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley—their most extensive exhibition to date, containing a generous selection from their collaborative work over the last three decades. Perhaps as a result of the hyper-referential yet opaque nature of their work, which the artists themselves describe as ‘highly condensed’, criticism—especially in the form of critical judgment about the success or failure of individual works—risks being superfluous.

Take, for instance, Bricks and Buttercups (2016), the latest in a series of neon works begun over a decade ago. In wall-mounted bricks, neon tubes and other sculptural elements, the work depicts a scene derived from George Herriman’s absurdist early 20th century comic Krazy Kat. Ignatz the mouse throws bricks at Krazy Kat, who, oblivious to the mouse’s aggression—in the comic strip, Krazy Kat is hopelessly besotted with Ignatz and mistakes his projectiles are love letters—bends down to smell a flower as the bricks sail over his/her head. Formally, the work approaches incoherence: the constituent parts are clumsily strewn across the wall (especially the flower and text, not executed in neon, that sit below the main image), sorely missing the boundaries of the comic strip or page; the disparity between the heavy, bulky bricks and the almost incorporeal neon refuses to allow the work to properly synthesise into an image. At the same time, the work does not push this formal and material incoherence to the point of making it appear truly at issue, as if it were engaged in a formal deliberation on the limits of structure, unity, coherence, and so on.

A formal judgment like this is, of course, probably beside the point. The real content of the work is in its reference to the Krazy Kat comics, its pointing to this phenomenon outside the gallery. Along with the films of the Marx Brothers, Charlie Parker’s alto solos and the boxing matches of Jack Johnson, Herriman’s Krazy Kat belongs to the pantheon of 20th century popular culture celebrated by early-to-mid-20th century avant-garde and modernist artists: writers like E.E. Cummings and Jack Kerouac sang its praises and any Philip Guston fan knows how important the artist’s return to his childhood imitations of Herriman’s comics was for his late turn to figurative painting. All of which is to say that there is nothing particularly novel in the reference to Krazy Kat in an art context. In fact, this lack of novelty appears quite deliberate on Burchill and McCamley’s part, as the artists acknowledge the precedent set by Elaine Sturtevant, the legendary forerunner of appropriation art known for her imitations Warhols and Oldenburgs, who made a Krazy Kat piece in 1986.

The claim is often made in interpretations of Sturtevant’s work that her inexact copies of existing artworks function to bring them into new historical and cultural contexts. What might be the meaning of Burchill and McCamley’s gesture, understood in these terms? Perhaps their interest is in the gender fluidity of the central Krazy Kat character, which is never stably assigned a male or female pronoun in the comic, making Herriman’s work surprisingly topical. But, if this is the case, the work does not make this link to contemporary discourse explicit in any way.

If this were to be phrased as a criticism of the work, then it would be obvious to respond that, like ideas of formal coherence or originality, the value of directness it implies is one that the artists simply do not accept. The figure of Krazy Kat is here at once a formal device, an art historical reference and a political allusion. Equally, it is none of these, because the work in which Burchill and McCamley presents the figure does not appear to really want to be visually compelling, to say something particular about art history, or to make a specific political statement. Making any of these three aspects of the work into grounds for a critical judgment risks irrelevance by praising or blaming the work for something it has not set out to do. Bricks and Buttercups is a perfect example of the ‘highly condensed’ nature of Burchill and McCamley’s work: its aim seems to be a kind of density of formal, art-historical and political reference that deliberately refrains from pushing any of these references to the point of saying (or doing) anything in particular This cool, reserved style of opaque referentiality roots Burchill and McCamley’s approach firmly in the 1980s postmodern context in which their careers began. The early work displayed here is an important reminder of the intertwining of art practice with film in the early 1980s, a time when Laura Mulvey’s Lacanian-Marxist approach to feminist film theory, in particular, had more to offer to young artists than traditional art history. Both Burchill and McCamley studied film in this period, and their early collaborations included super-8 shorts and photographic works making reference to film history.

One of the latter, Temptation to Exist (Tippi), (1986), from which the exhibition partly derives its title, remains one of Burchill and McCamley’s most powerful works. Two different crops of what appears to be the same image of Tippi Hedren, mounted on aluminium and separated by a thin black bar, depict the actor’s face glamorously made-up yet streaked with blood after an attack from the titular birds of Hitchock’s 1963 film. Showing the strong influence of the Pictures Generation (Cindy Sherman, Sherri Levine, Richard Prince, and so on), the work uses its appropriated imagery to generate a complex effect that can perhaps be understood though reference to key themes of Mulvey’s film theory. The doubling of the star’s beautiful but brutalised face suggests the perversely doubled nature of desire in Mulvey’s account of the male spectator’s relation to the cinema, in which the woman on screen is both a source of scopophilic pleasure and a threat that must be tamed, even punished, by the male protagonist. But equally this doubling of the violence inflicted on Hedren suggests Mulvey’s account of the female spectator’s oscillation between two positions, both equally violent, of masochistic identification with the female image and sadistic identification with the male protagonist. In the form of this materially imposing and formally elegant object, with its subtle play between symmetry and asymmetry, the ambiguity of Burchill and McCamley’s suggestions results in a work that carries a poetic, even emotional charge.

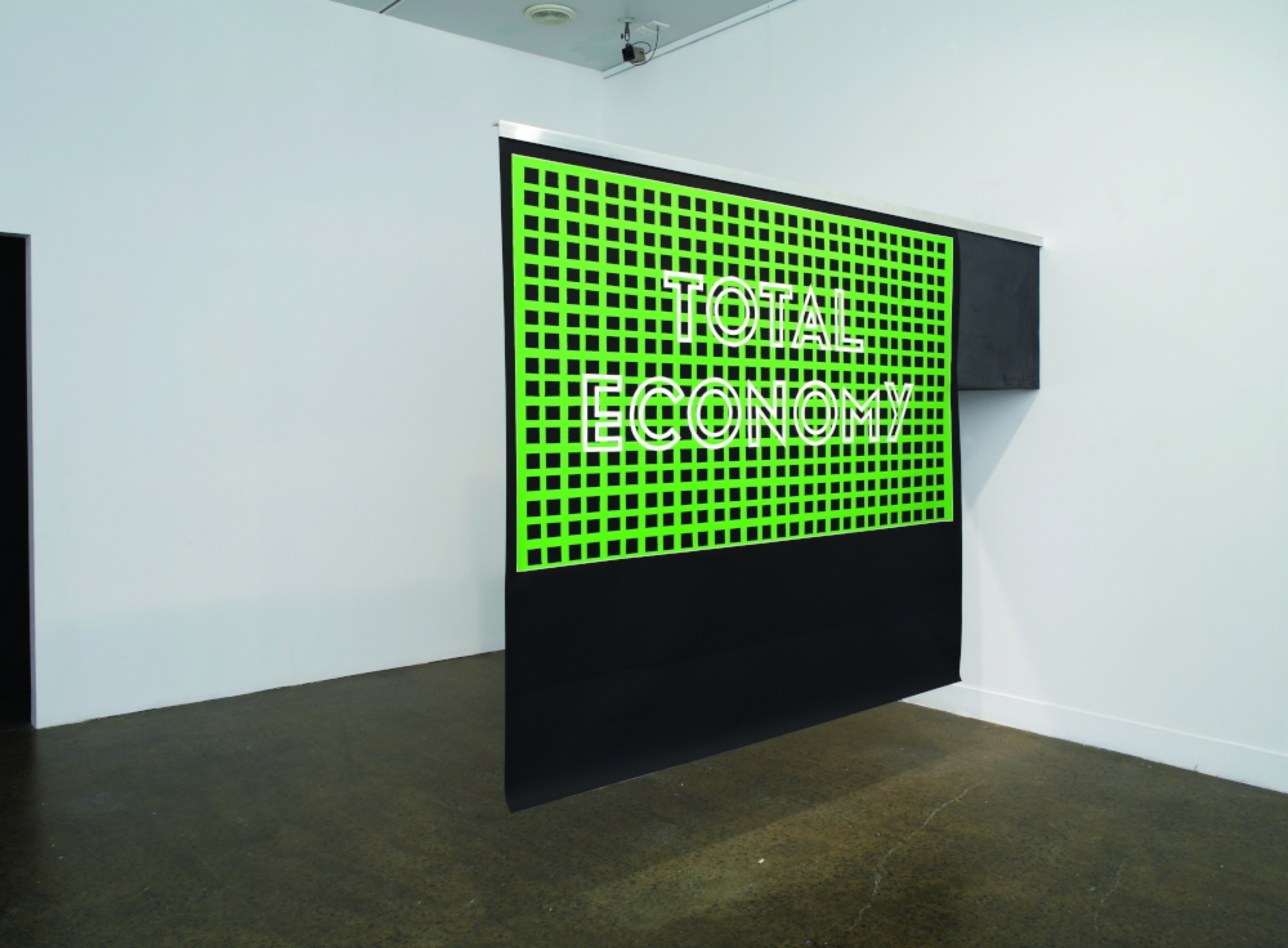

The same cannot be said for a series of works that exemplify one of the most tired aspects of 1980s postmodern discourse, the revision and critique of high modernism. Works such as Burchill’s Orange Race Riot (1998) and collaborative Total Economy (2007)—both reproduced in the catalogue but not included in the exhibition—fail to achieve the ‘highly condensed’ effect of the artists’ better works. The critical take on high modernism implied by Total Economy, a green grid with the title phrase painted over it in white, with its suggestion of some connection between the formal economy of modernist abstraction and the sinister-sounding notion of ‘total economy’ (the global spread of neo-liberal capitalism, perhaps?) has an undergraduate air. Orange Race Riot refers to Warhol’s famous 1963 silkscreen paintings, from his ‘Death and Disaster’ series, of images of police brutality against African-American civil rights protesters, complicating the formal autonomy of modernist hard-edge painting with reference to politics and presumably suggesting that colour can never be separated from its cultural and political meanings (including race).

The problem with a work like this, as Rex Butler already noted in the 1990s, is that such revisionist approaches to modernism make themselves redundant through their very success. That is, the modernist discourse of autonomous art has been so successfully complicated since the heyday of postmodernism in the 1980s that this revisionist critique is now the mainstream approach to modernist art. That the values of formalist modernism are inseparable from socio-political questions disavowed by its proponents is in fact ‘the only thing we bother to think about modernism’. This weakness is particularly notable in Orange Race Riot, which adds very little to Warhol’s own Mustard Race Riot, where the shocking imagery is complemented by a second monochrome panel in mustard yellow, famously explained by Warhol as a way of raising the prices of his work. Burchill and McCamley carry on Warhol’s evacuation of the sublime associations of the modernist monochrome field in their reduction of the formal language of modernist abstraction to a banal sense of good design; but as Hal Foster enquired of the ironic Neo-Geo abstraction of the 1980s, we might ask: ‘do they receive abstract painting as so reified, or do they participate in its emptying out?’

A number of works featured in the exhibition express similar concerns through an engagement with the history of modernist furniture design. Much more interesting are the artists’ most recent works with chairs, the pair of Falling Water sculptures (2015), in which car seats custom-printed with kitsch images of waterfalls are displayed atop concrete plinths. We might say that these works perform an exemplary operation of contemporary art, that of illuminating a new medium or support structure. If we understand the result of the post-Duchampian breakdown of the limitations of traditional artistic mediums (corresponding to the creation of what Thierry de Duve has called ‘art in general’) not to equate to the evacuation of self-reflection on the medium from art—in favour of ideas that can be expressed in a multitude of forms—but rather to the radical opening up of what counts as a medium for art, then we can understand the plurality of material supports found in contemporary art practice as results of an aesthetic search for unconventional, often everyday, mediums able to become the independent subject of aesthetic investigation and the support for an artistic practice. Thus we might say that the strength of the Falling Water sculptures is precisely their absence of specific statement, of any clear cultural ‘meaning’ being imputed to these car seats. The very arbitrariness of the decision to decorate them with images of a waterfall draws our attention to the car seat itself as a kind of medium; and in so doing it generates a characteristic aesthetic effect of contemporary art, a kind of sublime acknowledgment of the infinitude of possible mediums, each amenable to its own practice of experimentation, analysis, and dissection.

A number of recent works in the final rooms of the exhibition announce a dramatic shift in subject matter: out of the semiotic fog of Burchill and McCamley’s cultural references, nature suddenly appears. It takes the form of cast fungi (Throw Field, 2019), cacti (Arc Landscape, 2004), and most intriguingly, a series of bird’s nests in bronze displayed through holes in a wall-mounted cabinet that simultaneously recalls Donald Judd and the kinds of observation windows found in recreations of animal’s burrows at the zoo (Wall Unit (Origin of the World), 2001). Though Sue Cramer’s catalogue essay attempts to downplay this ‘surprising sidestep’ by arguing that what interests the artists here ‘is not nature per se but its interrelation with culture’, these works strike me as quite outside the purview of the artists’ other work, introducing an almost romantic note. Though the casting process necessarily destroys the fragile nest and transforms it into cultural object, the finished bronze stills captures something of the beauty and delicacy of the natural phenomenon. McCamley states that the artists see these bird’s nests as ‘mini-architectures and habitat units’, a singularly unenlightening comment: who, one wonders, would not see them this way? But, paradoxically, this failure of the artists’ discourse on their own work is the sign of exactly what is interesting about these pieces: here, finally, we have a sense that their work reaches beyond the game of deliberately ambiguous cultural references to try to capture and express something about experience.

Francis is a writer and musician from Melbourne.