James Nguyen: Open Glossary

Declan Fry

I’d planned to begin this piece with a fracture: on one side of the stage, the before, my attempt to visit the Open Glossary exhibition without actually visiting it. My travel aids: James Nguyen’s Open Glossary exhibition guide, his book Làm Chó Bò ~ Making Trouble, and Denise Ferreira da Silva’s essay “1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞ / ∞: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value.”

In each of these aids, language is made to perform a specific function. In da Silva’s essay languages normally considered in isolation from one another are placed in conversation (the language of mathematics, the language of historical materialism, languages that have equated race and value). The international status of English—its ubiquity—means that non-Anglophone countries regularly have to see, hear, and be made aware of English, whether intentionally or otherwise. Meanwhile, Anglophone countries in the main tend to work almost to avoid the languages of others.

On the other side of the fracture, the after, perhaps stage right or left: after having visited the exhibition, I would square the language of its actuality with my own invented tongue, the language I had created from first entering the exhibit purely via its texts and whatever materials I brought to my reading of them.

Unless the viewer of Open Glossary is enviably multilingual, they are unlikely to know every language the glossary invokes. Indeed, we never learn every language that makes up a life, whether our own or someone else’s. Hence we must be collaborators. Open Glossary represents just such an invitation to collaborate, one the audience may take or refuse. We reference the work of others in our texts as a way of building community, of offering the audience an invitation they can choose to take or to ignore as they wish.

So: What does the invitation present? To go home? To meet familiarity on familiar terms? Whose familiarity? Whose terms? Whose home?

Open Glossary is a compact exhibition. A children’s exhibition is in one space, James Nguyen and Kate ten Buuren’s Lerty’s Song (2023), whose wall is filled with paintings, zines, costumes, sculptures designed from felt and wire, vivid exclamations in a flurry of languages (สวัสดี!こんにちは、愛してる^_^ 哈嘍! 안녕하세요!), dioramas, depictions of journeys (one drawing depicts the Eiffel Tower beside a sunstruck Australian shore). Each was prompted by the exhibition’s invitation to reflect on connection to Country and caring for Country. Beside it is James Nguyen and Budi Sudarto’s White shirt installation (2023), a maze of shirts through which the audience wanders, hearing the voices of interlocutors talk about sexuality and life in Australia in a variety of languages. Linguistic variety both introduces the exhibition in its five-language title and is followed through to its end-space, James Nguyen and Budi Sudarto’s Angel Costumes (2023), whose many languages—Malay, Thai, Chinese, Korean, Spanish—invite the audience to see questions of gender and sexuality given voice and materiality through linguistic avowal. I recognise in the angels’ wings a few words: espéctro de genero, Spanish for ‘gender spectrum’; the simplified Chinese for ‘lesbian’ in 女同性恋者.

I first entered the exhibition via its catalogue and two of the languages I was familiar with: English (the first one to greet you as you enter the exhibit or turn to its opening page), and a piece in Chinese about New York-based freelance ethnographer Chris Xu’s “Letters for Black Lives,” titled “翻译与交流, Translation and Connection.”

I read Xu’s work—which talks multilingually about multilingual experience—in Chinese before entering its English half. “Letters for Black Lives” is set in America but broadly addresses the role of diasporic communities in other settler-colonial states like Australia. In Chinese, Xu describes speaking about race in America with their parents. This is a kind of everyday translation experienced by many families with differing degrees of familiarity with the majority language. Younger members translate for the older ones and in doing so open the possibility that these acts of translation may be passed on, speaking to others.

The material world and its crises tend to rejuvenate and incite dialogue with family and familiars. Xu states that translation is a problem: their Chinese remains at a child’s level and their parent’s English has been self-taught from daily life; the problems of race at the core of the Black Lives Matter movement have never entered these spheres. Xu writes a letter in English and crowdsources a community of translators to put it into Chinese. In writing of a desire to communicate the idea behind the Black Lives Matter movement in a way that speaks to their parent’s values, Xu is also describing the matter of what matters, which is to speak in a language that resonates in the life-worlds people move in. (Even the Chinese version communicates this: 黑人的命也是命, or “Black People’s Lives are also Lives.”) A life is one we recognise as such: as something worthy, whether of another language, culture, race, gender, sexuality, religion, or design. Xu’s experiment in collaborative translation offers an example of minds meeting, “To come to consensus because a paragraph can only tolerate so many parentheticals.” What might such a community look like, with so many others incorporated into it?

Language entails a shift in perception. It may be a banal observation, but that does not deprive it of its significance. To read, in Xu’s reflection, of 美国 (meiguo, “America”), is not to read of the same place that the word “America” connotes in English. (Or, for that matter, the same place 美國—the traditional Chinese word used in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan, with their own particular linguistic and cultural histories and experiences of the country—connotes). 美国 resonates differently in Chinese on the mainland: it is both the power from which Mao’s China grew apart and a place whose arrival on the mainland in the eighties saw decades of postwar Western culture arrive in a sudden, telegraphed rush. When we speak of 美国 we are speaking of a very different place to “America,” both temporally and geographically. Words re-create the things they describe; what they describe does not exist before them but comes into being as a result of them.

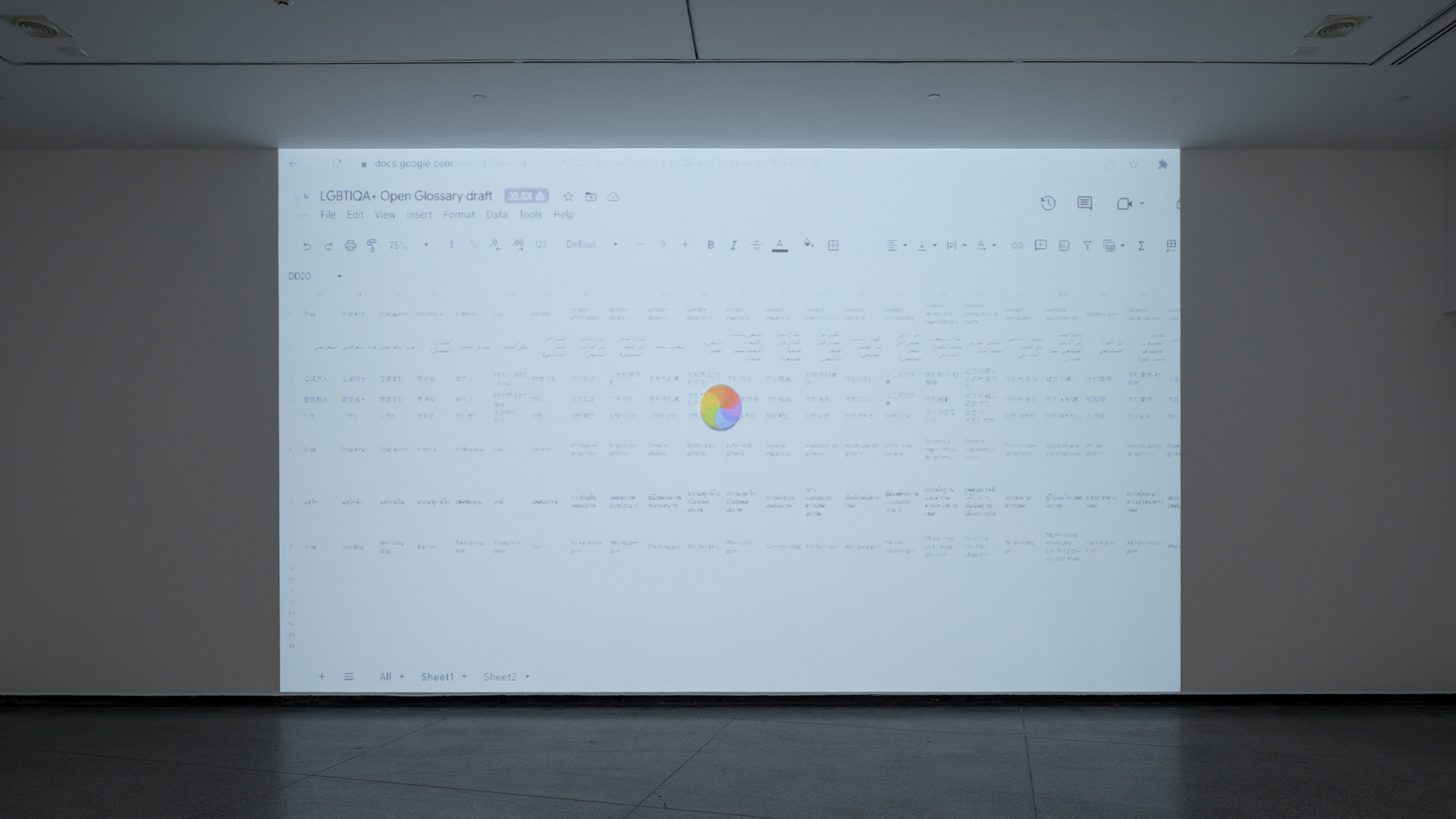

In conversation with Nguyen, ACCA’s Senior Curator Shelley McSpedden gives a wonderful description of meeting places as 会 (hui), encounters. In establishing relationships and communities, 会 becomes both an invitation as well as a moment of “obligations and responsibilities, the tensions and the conflicts of that encounter” (it is interesting to note here that 会 can also be used to indicate the future tense in Chinese, a marker of something that will happen). Communities with conflicting demands and obligations coexist, raising the question: what is allowed into a glossary? Sometimes translation fails at the border, because it cannot accommodate everyone inside the gates. As Nguyen remarks in conversation with McSpedden, “When you’re working with a gallery, there’s this expectation that when you’re queer, you want to celebrate it and be outrageous. And you want to bring your ethnic community in. But actually, that’s really dangerous. What if my parents get ostracised? And I’m not in Sydney to give them the social support that they need. So it’s always very complicated.” Describing their decision to limit the original project of creating an open, live, digital document in various languages of Western queer terminologies in favour of a more restricted one, Budi Subarto and Nguyen say simply, “We are hopeful in unhopeful times.”

Who participates in language? Who is left out? What communities does language speak for or on behalf of? Who is integral and at what cost? In White shirt installation (2023), a donated array of plain white collared shirts forms a maze through which the audience walks—a maze punctuated by a set of Ariadne’s threads, different people speaking about living in Australia, in English and in other languages. This exhibit threads together the predominance of the white collared shirt in Asian cultures—as symbol of middle-class respectability, of worthiness under regimes of settler-colonial capitalism—with its material value as part of the manufacturing industries that are so densely interwoven with both former and current clothes manufacturing industries in Asia and the global South. For Nguyen’s family, matriarchal piecework kept them afloat, allowing them to participate more fully in the world.

Languages thus produce hidden economies. Consider the black market of migrant labour that takes place, outside the dominant language, in precarious conditions across developed countries. One of my favourite stories concerns the phrase “fair dinkum,” an almost comically “Aussie” settler-colonial slang meaning that something is the “real deal.” The story goes like this: at the heart of this most “true blue” of words is a southern Chinese dialect, perhaps Cantonese, which was misheard or Anglicised by White settlers hearing southern Chinese miners during the gold rush cry 真金! (Zan gam! or Real gold!; try saying zan gam aloud and you will probably hear the resemblance to dinkum). The real deal indeed.

This story reminds us how language, culture, race, and nationality can come untethered or be re-understood. Language and ethnicity—to say nothing of citizenship or culture—do not have an intrinsic or indissoluble connection. They often conceal or contain the traces of other languages, histories, and cultures that have informed them.

As the Hanoi-based artist and activist Nhung Đinh writes, describing spoonerisms in Vietnamese sexual expressions, if the sexual relationships or orientations of the speaker are unclear, a sense of openness emerges about “the possibility and positionality of these sexual relationships, their subjects, and how we ourselves relate to people with our preconceived judgements and assumptions.” (I am reminded here of Anne Garréta’s 1986 novel Sphinx, in which the gender of the two lovers at the centre of the novel is never spelled out, something that imposes its own linguistic constraints and navigation in both the gendered norms of the original French, as well as English and the other languages it has been translated into.)

Although not featured in the exhibition proper, academic and artist Dr Kirsten Lyttle has a bilingual reflection in te reo Māori and English in the exhibition’s catalogue. In “Tora Hui” (“Three Hui”), Dr Lyttle describes learning the te reo Māori language and discovering that one phrase, “hello family,” does not appear in her textbooks. I am reminded that the language taught to outsiders often differs from that of native-speakers: in Japanese, the term wareware, for example, occurs frequently but only rarely used by non-native speakers, since its associations with ethnic and national identity—as in われわれ日本人 (ware ware nihonjin, “We Japanese”)—are so common, a link strengthened both through usage and association. Even the name of the Japanese language changes depending on who is using it: 日本語 (Japanese) is the language taught to those outside Japan; inside Japan, it is not 日本語 that is taught but 国語 (kokugo), literally “nation language.” (Chinese makes different yet not wholly dissimilar ethnic distinctions: while the language in the abstract might be called 普通话, putonghua (common language), it can also be called 汉语, hanyu (language of the Han), an issue further complicated by geography and cultural history: in Taiwan, for example, even if someone like me, who is not ethnically “Taiwanese,” were to speak Mandarin, many people would say I was speaking guoyu, nation(al) language, even though this would almost never happen were I to speak the same language on the mainland.)

There is thus a mystifying aspect to language beyond its straightforward communicative function, a mystery which writers work with as part of their practice. As Yoko Tawada writes in her essay collection Exophony, describing the experience of “not hearing” French (due to not understanding it), language, freed from the conditioning and restraint of usage and meaning, can sometimes become more visceral: “My whole body became an ear” (全身が耳になってしまう).

Open Glossary is a testament to Nguyen’s concept of Làm Chó Bò or “making trouble”: how immigrants, perceived in Nguyen’s words as “simultaneously invisible and troublesome,” can take advantage of networks and collaboration to teach one another, create new stories and languages within the intersection of both adopted and personal histories—especially personal histories in which speaker and listener are both coloniser and colonised. At the same time, this collaboration can help to change the narrative that encourages colonisation and settler amnesia to continue untroubled.

Part of the underlying fabric of this “untroubling” lies in the conditional nature of modern liberalism, allegiance to which will not protect you. For example, Nguyen’s family became involved in piecework just as the Labor government elected to float the dollar in 1983, stimulating the banking and mining sector while hollowing out lower paid, lower skilled manufacturing, disproportionately affecting immigrant and non-fluent English speakers. Nguyen spoke movingly at the exhibition’s opening night of learning that, while his mother supported the family with piecework, she had, unbeknownst to him, also been writing poetry in Vietnamese. This piecework—which continues to this day—sponsored Nguyen’s auntie over from Vietnam, paid off debt, took care of school fees, and allowed Nguyen’s father to return to university and qualify as a social worker. On the other hand, Nguyen states: “My Mum, and to a lesser extent my Aunty, emerged from this process with profoundly bad English. Mum’s relentless piecework prevented her from gaining the language skills to actually leave piecework.”

Nguyen also describes learning about the feminist and orthographic traditions of the Vietnamese folk script Chữ Nôm (𡨸南, “Southern characters”). This script, like Japanese, took its form from the Chinese language while reshaping that inheritance to fit the local language. (Informed by Nguyen’s reference to the language, I am fascinated to learn that it has another name, one very similar to 国语 / 国語 / 國語: Quốc Âm (國音), or “National sound.”

What is this “national sound”? If it is to be something other than brute nationalism, I believe it must be personal—personally incorporated, personally voiced and felt. (And the “personal,” here, need not be the self-contained Western subject). Taking back the language in order to speak to settler-colonisation, Nguyen’s Aunt insists on voicing their Acknowledgement of Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung Country in Vietnamese. Just as gaps in language for Xu, with their struggles to communicate in Chinese, created opportunities rather than deficiencies, the Vietnamese Acknowledgement is an opportunity to remember (or hide—not all pain can be shared or accommodated) both the injustices of various homeland(s), adopted or otherwise, as well as a contribution to the ethics of what it means to live in Australia today, amidst our different struggles, displacements, and needs. What Nguyen reminds us of is that language-brokering for intergenerational migrants can become a form of political activism, helping to fight political disconnection and cultural estrangement. As the draft Acknowledgement of Country at the exhibition shows, acknowledgement is not a performance or a token but a particular act in a particular time and place that the speaker takes responsibility for. It demands thoughtfulness about what it means to speak of a particular Country, and the speaker’s (and their communities’) relationship to that moment of Country. The collaboration between Ngyuen and his Aunt on a Vietnamese Acknowledgement shows this, right down to the need to choose from among the possibilities of translating a term like “unceded land”:

We decided to spell it out (the meaning of “unceded land”) in Vietnamese. Saying trên mảnh đất này bị người khắc lấy đi, mà không phải nhường ~ on this piece of land that was taken away by other people but was never offered up/given away. To my Aunty, the clarity of saying how the land bị người khắc lấy đi ~ was taken away acknowledges the actuality of forced land theft, making it specifically resonant for herself and other potential Vietnamese-speaking audiences whose lands and property were taken away throughout our various wars. To Dì Nhung, the memory of having land, friends, and family taken away and put into reeducation camps was something that she can không bao giờ quên ~ never forget.

There is solidarity in language, in linguistic collaborations, in translation, in re-engaging with forgotten or non-fluent languages. This can be seen in Nguyen’s Aunty’s reflection on the Vietnamese term for Country: Đất Nước, which literally translated means “Soil Water.” Đất Nước offers a potential for awareness of Country in Australia, of Country as land and waterways, and for communicating this with family and community. A composite is possible, as every translation is a palimpsest—a palimpsest that does not displace what lies beneath it but allows it to coexist and remain visible within the open mesh weave that the work of translation makes possible. Nguyen and his Aunt take Acknowledgement of Country as an opportunity not only to think about the implications of living on đất bị cướp or “stolen land” but to live them, refusing the dominant language. They acknowledge Country in a language that has seen its own violent massacres and land dispossessions—some of which Nguyen’s family have known firsthand—even as Nguyen’s family, like millions of other internally displaced Vietnamese refugees, were resettled in South Vietnam under a scheme that saw the displacement of Southeast Asian minorities and First Tribes.

Open Glossary builds on activist work like that of the Anticolonial Asian Alliance, designed to create new connections across diasporic and migrant communities while speaking back to the dominant narratives of the homeland, whether voluntarily or involuntarily adopted or left behind. They create new linguistic and cultural connections, refusing estrangement or complacency in favour of, as Nguyen writes, “self-reflection, collaboration, archival production, language-sharing, and knowledge production.”

In Yoko Tawada’s 2004 novel The Naked Eye, a work written simultaneously by Tawada in Japanese and German and thus not easily traceable to a single “original” or “first language,” a young Vietnamese woman is invited to speak at an International Youth Conference in East Berlin. She is kidnapped and finds herself on the other side of the Berlin Wall, before escaping to Russia and then to Paris. Alone and penniless in a foreign land, at one point she says to her kidnapper:

そのうちにヨルクの顔がまた視界に入ると、思わずロシア語になって、「家に帰りたい、家に帰りたい、家に帰りたい」と叫んでしまったが、なんだか外国語でそう言うとうそのように聞こえた。

When Jörg’s face appeared in my field of vision again, I screamed in Russian: “I want to go home, home, home!” In a foreign language it sounded like a lie.

By taking on the responsibility of making and living an Acknowledgement of Country in our mother tongue(s), speaking becomes a contractual compact—one that acknowledges our multiple histories and complicities, unsettling our settlements. We become someone who refuses the lie of coherence and, in so doing, refuses to speak of a home whose invocation itself risks becoming a lie. Refusing to speak thus, we grow to love the story whose truth we live.

Declan Fry is a writer currently based in Naarm.