Vivienne Binns: It is what it is, what it is

Helen Hughes

Vivienne Binns seems to have taught—or had some sort of mentor-like relationship with—a whole bunch of artists whose work I like: Charlie Sofo, Liang Luscombe, Trevelyan Clay, Kate Smith and Geoff Newton, to name just a few. If there is amongst some or all of these artists a shared sensibility to do with humour, a cavalier attitude towards painting (or 'fine art' in general), a commitment to abstraction, patterning and the everyday, it is more than a little tempting to see Binns lurking somewhere in the background, as somehow responsible. Over the years, I've got to know Binns' work elliptically. We were taught about her now-canonical early feminist and community arts projects from the late 1960s to the early 1980s in Australian art history subjects, but these—not surprisingly, some forty years later—seem at a remove from the very particular painting practice of hers that I've come to know in recent years. Rather, I feel I developed the strongest sense of her work through anecdotes told by these artist students, and through the spectral traces of her practice that seem to be expressed in their own work. Indeed, the intergenerational and discursive model offered by teaching in an art school, where ideas, techniques and pools of knowledge are thrown around often casually, is a useful one for thinking through the impressive body of work that Binns has produced over the last five decades. Binns' solo exhibition at Sutton Gallery, entitled It is what it is, what it is, afforded me a chance to test this proposition.

Though she is renowned for her metal enamelling work of the 1960s and '70s, and is often hailed as a pioneer of both the community and feminist arts movements in Australia, It is what it is offers viewers a substantive look into Binns' career as a painter. It spans nearly twenty years of her painting practice (the earliest works date 1988, and the latest 2016), and has been put together by Binns' long-term Melbourne gallerist Irene Sutton. Those already familiar with Binns' practice will recognise many of the works in this show, with them having been exhibited in the two major retrospectives to date (one at La Trobe University Museum of Art in 2012, and the touring solo show that began at Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in 2006). But for the uninitiated, It is what it is is timely because it arrives at a moment when Binns seems to keep popping up with individual inclusions in bigger, thematic group exhibitions around Melbourne. For example, she was represented as a 'focus' artist in the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art's 2016 exhibition Painting. More Painting, and she likewise cameoed in ACCA's more recent Unfinished Business: Perspectives on Art and Feminism. As well, in late 2017, Binns was included in the important homage-exhibition I Love Pat Larter at Neon Parc, Brunswick, which was curated by her former student and collaborator Geoff Newton. Each of these group exhibitions presented Binns as a thread in a weave—as painter, as feminist, as peer. By contrast, It is what it is is special because it allows us to look at Binns' practice in isolation. And it allows us, I suggest, to look at Binns' painting practice as a type of weaving process itself.

At least, It is what it is almost allows us to look at Binns'work in isolation. Perhaps due to her background in community arts, it would seem that the Canberra-based Binns—not unlike the artist, writer and teacher Lisa Radford in Melbourne—cannot help but extend invitations and share opportunities with others, and particularly her former students. Binns' exhibition in the main space at Sutton Gallery is accompanied in the smaller space by a group exhibition of work by three former students—Dionisia Salas, Chris Carmody and Fiona Little—that she has curated herself. I'll return to the significance of this later.

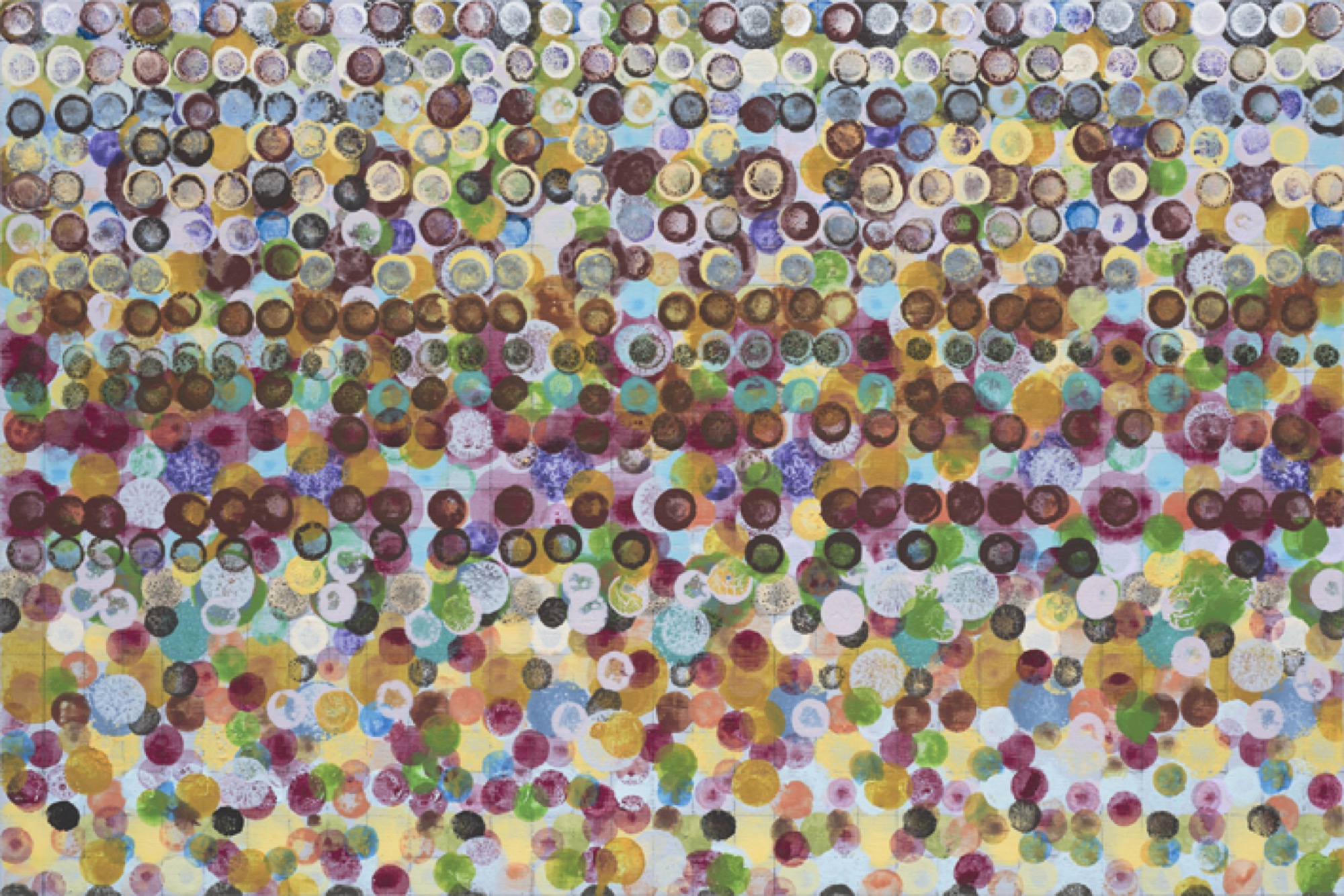

If you were to evaluate It is what it is on purely formalist grounds, you'd be quick to identify the compositional logic of the grid that clearly structures twenty-two of the thirty-one paintings presently on display at Sutton Gallery. Whether these are carefully traced horizontal and vertical lines producing squares, or diagonal lines producing diamonds or lozenges, or optically inferred by the overlay of evenly spaced dots, grids certainly do predominate. But, executed in an at times casual, wavering hand as they are in works such as Yukky Surfaces, 1999 or Surfacing in Memory, 1999 (both of which seem to bear more in common with a hastily played game of naughts and crosses on a napkin at an airport lounge than with, say, the exactitude of an Agnes Martin), there is clearly a humanity, humbleness and sense of humour at play here, one that is wholly lacking in the declarative works of twentieth-century modernism parsed by Rosalind Krauss in her famous 1979 October essay 'Grids'.

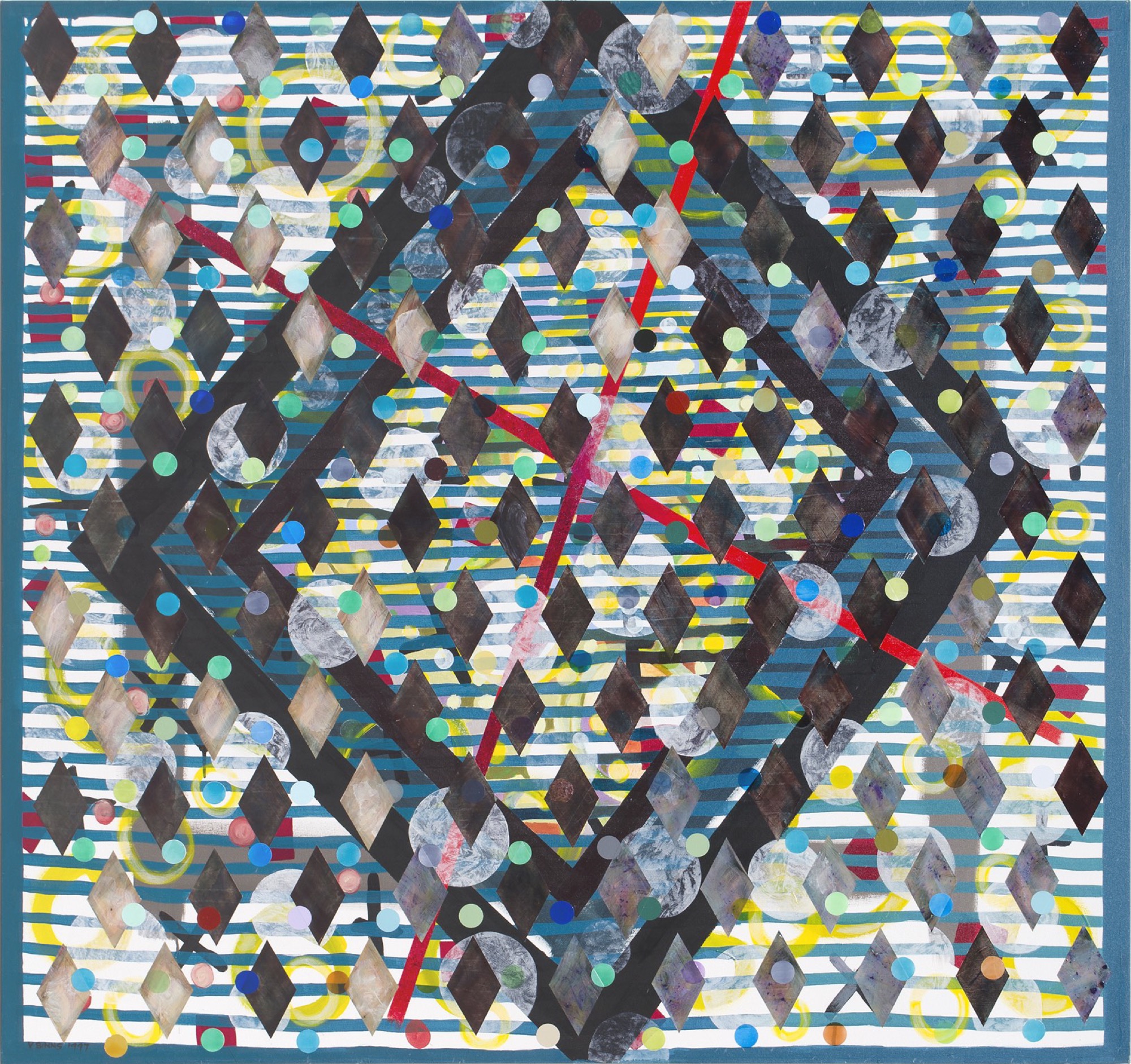

Krauss premises her study on the belief that the grid is exemplary of modern art's 'will to silence': it is the compositional strategy that banished everything to do with speech, narrative and language (and thus duration) from the optics of the visual arts. As a composition, she wrote, the grid is 'antireal', 'antimimetic'—'it is the result not of imitation, but of aesthetic decree'. Binns' grids, however, have a wholly different character. For a start, they are largely mimetic: they are usually based on decorative patterns gleaned from materials like friends' jumpers (as with the commanding From David's Jumper Mark II, 2007–8) or fragments of fabric collected from op shops or sent to her by friends (as with Gingham Thread, 1999). Rather than 'lowering a barrier' between the visual artwork and language, her paintings are utterly resonant—you can almost hear the myriad conversations with other artists, friends, family, and so on, that surely supported the production of these works. After all, a crucial chapter in the Binns mythology is the fact of her abandoning painting for some two decades due to her extreme dislike of the isolation that accompanies a traditional studio practice, embracing instead the sociality of a community arts–oriented practice.

As Binns scholar Penny Peckham has observed, her paintings bear something in common with those of the Australian late modernist Dale Hickey, who also turned to domestic sources in his painting practice. However, where Hickey 'takes inspiration' from such things as floor tiles only to turn them into geometric abstractions, Binns takes the tiles as the actual subject matter of her paintings—elevating these designs into the realm of fine art. Perhaps she is even painting their portraits. Stemming from her 1970s feminist reappraisal of the status of variously 'craft' and 'amateur' arts practices as 'fine art', works like David's Jumper and Gingham Thread relate to her series In Memory of the Unknown Artist, which pays homage to the decorators and pattern-makers of fabrics and other utilitarian objects that can be found around the house. Other paintings not only depict but directly appropriate such materials. Floating, 2000 and Lino, Canberra, Tile Formation and Overlay, 2001 both collage miscellaneous offcuts of linoleum flooring onto board, over which new details have been laid down by the artist in acrylic paint—a type of Cubist experiment. A funnier still Cubist-type work is the 2012 Little Ballerina, a small rectangular canvas whose bottom and upper edges are adorned with a fabric frill covered in glinting purple sequins. The painting's surface continues the fabric's chintzy pattern as a modernist grid infilled with circles painted in a range of purple-derived hues—these are paintings (portraits?) of the sequins, we presume, shown in an array of colours as caught under light. A semiotic displacement, this modernist grid is also, in fact, a realistic painting.

Binns' interest in the grid exploded in the late 1980s through her involvement with ARX (Artists Regional Exchange—a precursor to the Asia Pacific Triennial, but rather orchestrated by artists with a view to exchanging knowledge and skills). Here, she first properly encountered the production of tapa bark cloths and their designs, which, too, are often based on grids. Binns then pursued an active interest in tapa, visiting Raratonga in the Cook Islands in 1992 for the Sixth Pacific Festival where she was invited to participate in their production by the Tongan craftswomen there. Several of the works in It is what it is—most obviously Pacific Learning Again, Tapa Focus and Tapa Pattern over Scrap Ply from Hong Kong, all 1993—pay homage to the practice of tapa designs and their ability to hold collective stories. These works also possess a similar sensibility—and similar dispersal of authorship—to her earlier cross-generational and community-driven projects like Mothers' Memories, Others' Memories of 1979–81. Binns' turn towards tapa also helped her rethink Australia culturally and geographically. Her reimagining of the country of her birth saw a shift away from the traditional Australian isolationist mentality and towards the interconnectedness of the archipelagos of the Pacific Ocean. This shift in her thinking seems broadly in line with her commitment to community art practices and her dislike of the solo studio artist paradigm (which, of course, has much to do with second-wave feminist critiques of the individual-male-artist-genius—the critical culture in which her early works percolated).

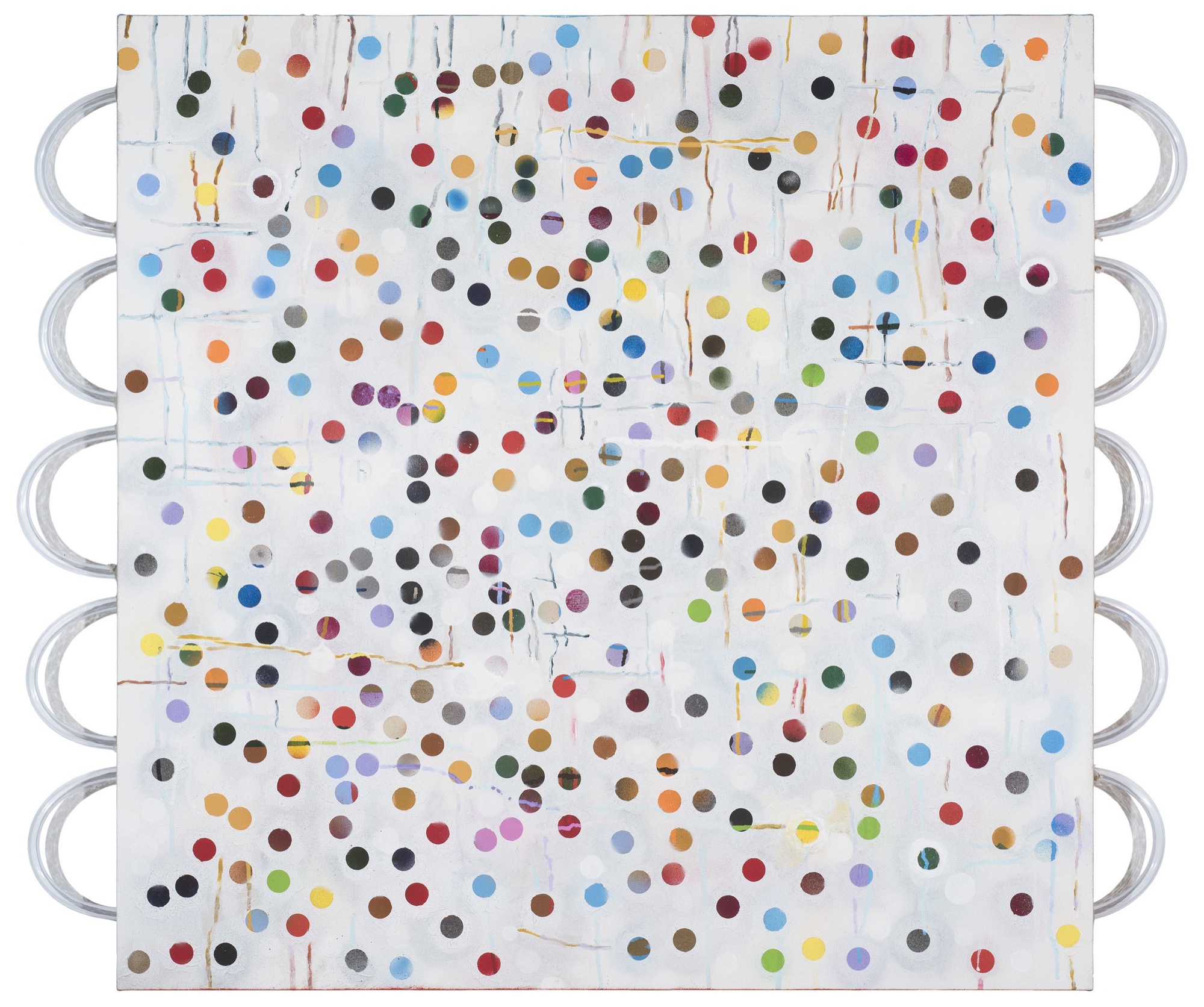

If the grid is a giveaway compositional device in Binns' work, then the other tell-tale characteristic trait is the void—the painterly wormhole that pierces her paintings' surfaces, offering portals into deeper layers, other paintings. The void shape began as a bombastic trope in Binns' sexual imagery of the late 1960s and '70s—most famously, the 'central core' imagery of her Vag Dens, 1967—then continued as a stand-in for the female sex in her small paintings on canvas boards Bush Ground: unstable image becomes; more from the allegory of the good girl … and Each One has a different name … is a different thing, both 1990. In 1997, it manifested again in the series of photocollages that include The Object which is more than One and This space can be rendered both, in which black vessels and gashes are vertically imposed on a grassy landscape. This compositional device is best demonstrated It is what it is with her 2008 painting Thinking of Pattie Larter and her untitled collaboration with Merryn Gates, whereby Binns in 2002 painted (or it may be more accurate to say 'combed') a black-and-white layer of wobbly stripes over the top of some fabric that Gates had herself painted in 1986 (it was for a harlequin costume she wore to an exhibition opening at the National Gallery of Victoria). Binns leaves biomorphically shaped 'holes' in her layer—apertures onto Gates's red, yellow, green and black triangular patterning that forms the underpainting. In this respect, we may be inclined to think of the late Robert Hunter, whose mesmeric, layered 'white-on-white' paintings too contain voids or holes onto subterranean layers of off-white house paint, which he also likened to vaginas. Yet where Hunter's paintings hinge on their uniformity and precision, Binns' layers are often executed in completely different styles, demonstrative of her decision to employ 'diversity as a deliberate artistic position'. Before the Eyes, 2013, for instance, is undergirded by a patchy Howard Hodkin–style abstraction, then striated by impastoed, combed lines over which two fields of spray-painted, Arkley-style gridded dots float. Other paintings, such as Big Drawing No. 2, 1997 reworked 2011, combine layers of alternately opaque and semi-transparent shapes and patterns, making it difficult to discern a top layer from a bottom layer. This technique scrambles our sense of the painting's temporality as well as its depth.

It's not just in Binns' students' work that we see continuity: for instance in the dynamic, jumbled surfaces of Dionisia Sallas's three prints on marbled paper, and the all-over, intricate patterning of Alice Little's mixed media works. Binns' practice openly evidences the heritage of her own teachers' too—particularly the off-kilter gridding and colour separation technique of Godfrey Miller, who taught Binns at the National Art School in Sydney in 1950s and '60s. As a student, Binns also studied closely the works of early Australian modernists like Ralph Balson, Frank Hinder, Anne Dangar, Grace Cossington Smith, and Grace Crowley. The three tiny canvas boards comprising ABUT, 1988, for instance, check the brilliant colours and pointillism of Cossington Smith.

Latterly, Binns has become renowned for spending a whole year working on a single painting. Her labour-rich works that overlay grids, build up layers, and use voids to point to the ontology of painting not as surface (as with the twentieth-century self-referential modernist grid), but rather as surfaces (palimpsest-like, as literally and metaphorically bearing the memory and trace of what came before) indicate the time of the painting as eventual, progressive, and also connective. This is the generous spirit of her painting as weaving, as a braiding-together of that which modernist avant-gardes would more readily shunt in their effort to create a rupture with the past. In these ways, Binns' survey It is what it is is unusual, yet also wholly typical of the artist's approach: her paintings simultaneously command and deflect attention.

Helen Hughes is research curator at Monash University Museum of Art, and an assistant lecturer in Art History and Curatorial Practice in the Faculty of Art, Design & Architecture at Monash University.

Title image: Vivienne Binns, From David’s jumper mark II, 2007–8, acrylic on canvas, 152.5 x 183.8cm. Image: Derek Ross.)