Bill Henson

Beth Kearney

Even now, it is difficult to visit a Bill Henson exhibition without being burdened by the controversy that occurred at Roslyn Oxley9 just less than nine years ago. Stylistically, however, Henson has not changed his tack: the exhibition Bill Henson, part of the NGV’s Festival of Photography, is yet another rearticulation of his most recognisable qualities as an artist.

Bill Henson was the first exhibition to open for the festival, which also includes other contemporary photographers such as William Eggleston, Zoë Croggon, Ross Coulter and Patrick Pound. Running from 10 March to 27 August, the exhibition includes 23 large inkjet prints capturing—as Henson has for much of his career—pensive nude youths, coastal landscapes at sundown, moving water, ancient ruins, and public museum spaces.

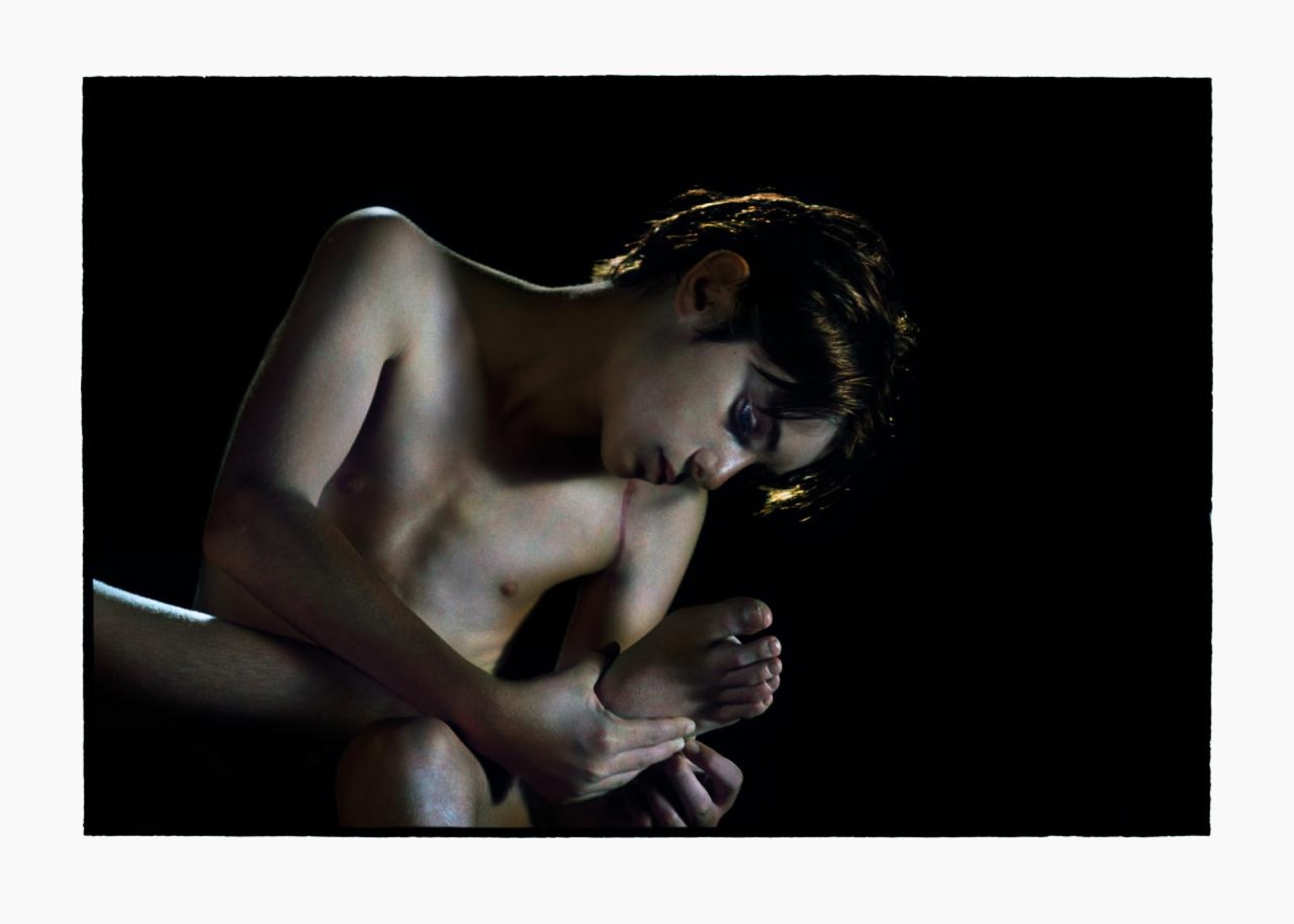

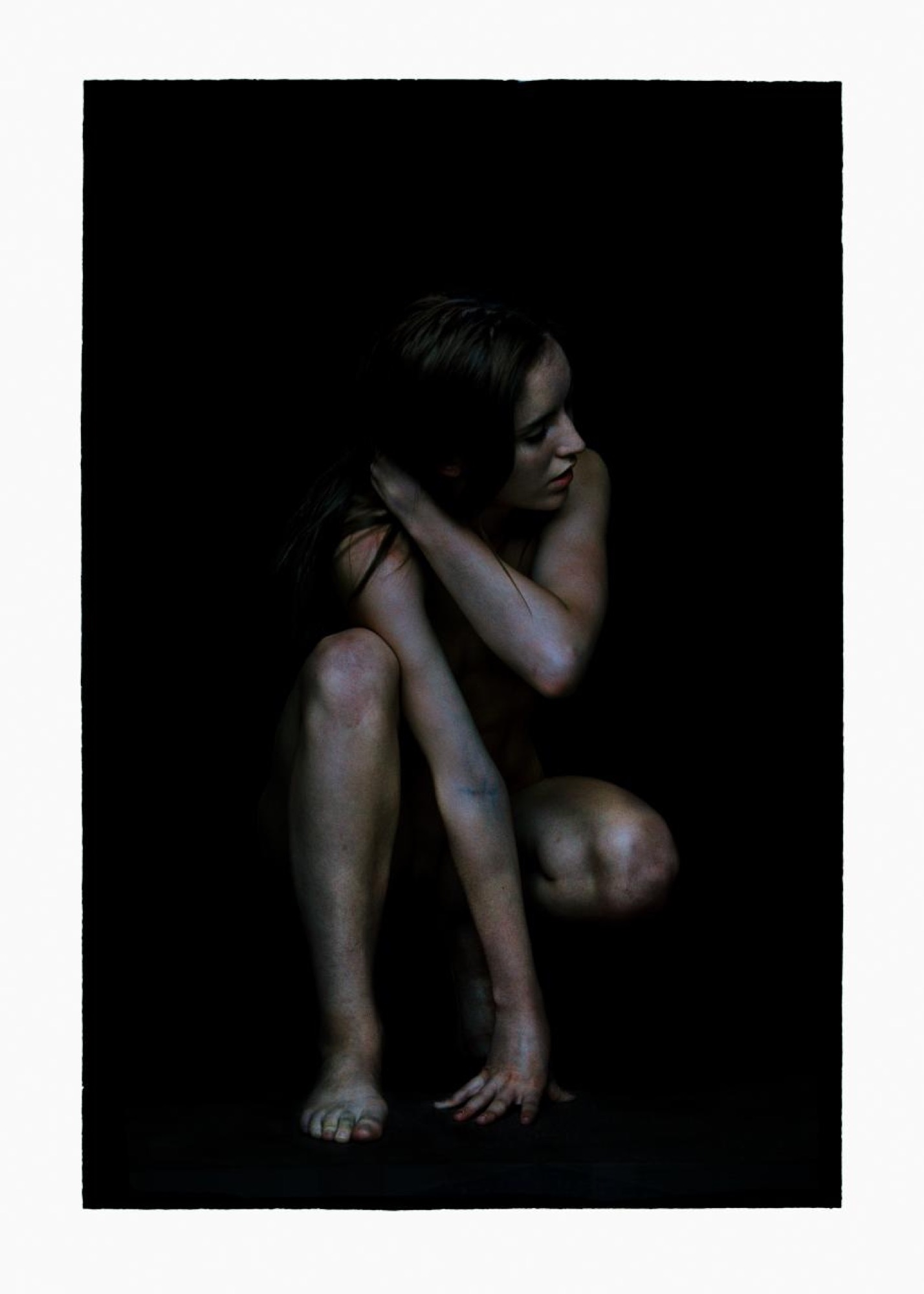

The well-known Baroque qualities of Henson’s work employ chiaroscuro, while his pre-production methods are detectable in the staged nature of his youthful subjects. Henson also continues to experiment with cyan hues, creating bluish undertones that enhance subtleties of depth, the appearance of kinetics in water and the visceral qualities of human flesh. Further, despite the arrival of digital media, Henson’s post-production methods do not aim for crisp, detailed and high-resolution photographic tableaux, but large textured prints that follow a painterly tradition.

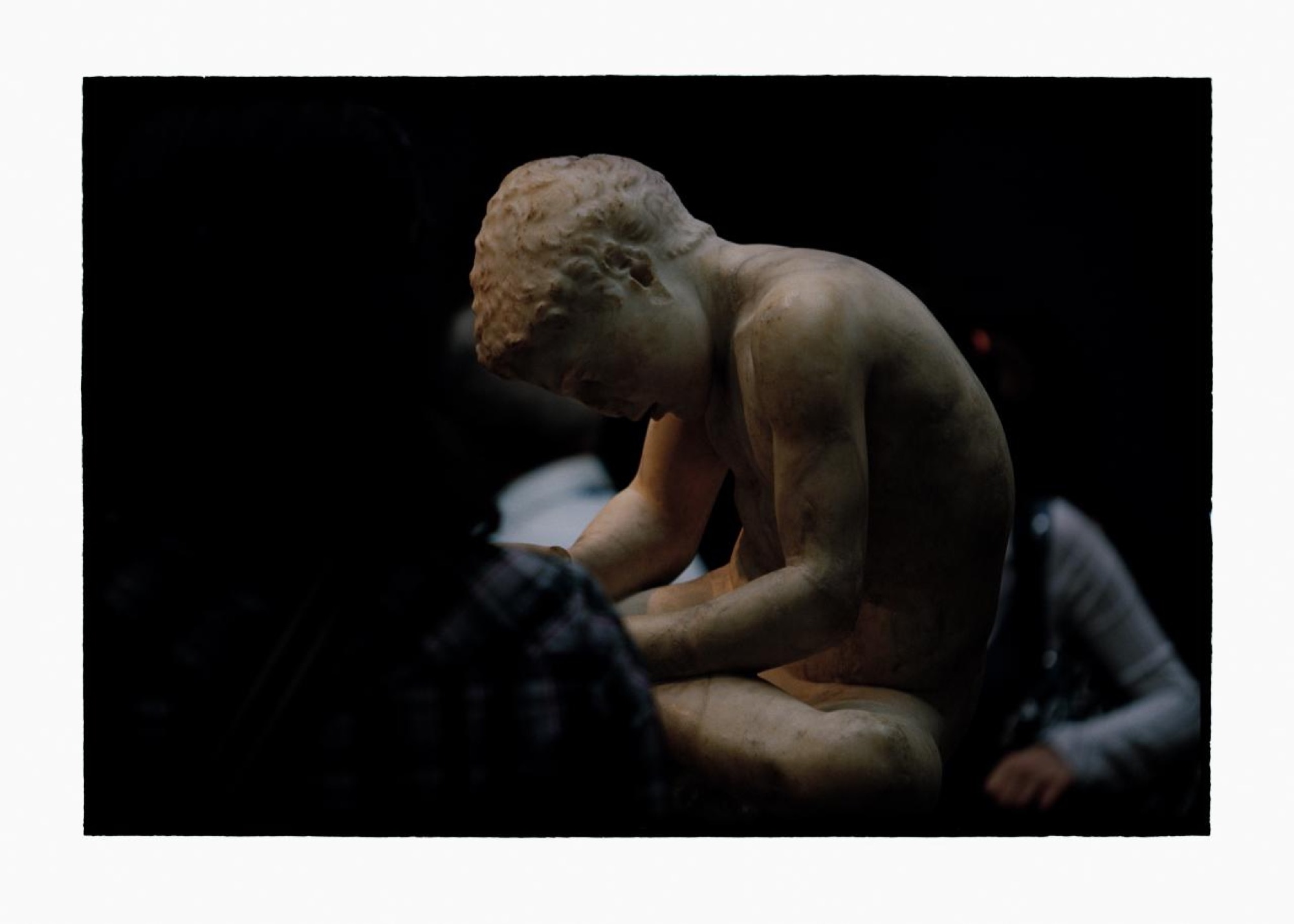

Henson’s theme of interstitial spaces is also typical of the artist’s career to date, and he explores this through various subjects. This continues unabated at the NGV. That is, Henson’s work figuratively meditates on the ‘in-between’. In his landscapes, shot during the transition between day and night, he focuses on the stillness of a bay surrounded by the turbulence of the water beyond. His studies of bustling museums depict these spaces as caught in-between contemporary life, as we see blurred and busy faces move past unmoving oil paintings and classical marble sculptures—his art pairs timelessness with the ephemeral, acting as a souvenir of the past. When photographing water, Henson’s camera captures neither its origin nor landing.

In his portraits, Henson’s young models are photographed at the threshold between childhood and maturity. While for some this aspect of his work is cause for discomfort, others admire the sensitivity and poetic lyricism of the approach; no longer children, his models are introspective adolescents on the edge of adulthood, coming to the realisation that they are not yet able to meaningfully act and react in the world.

Henson has long reiterated that his artistic aim is to create individual reflection on the part of his audience, stating that he wants the public to understand his work in ways unrelated to his own intentions. This unsolicited response that Henson seeks to bring about with his work was realised in the collectively fuelled public outrage caused by the Roslyn Oxley9 invitation to his now infamous 2008 exhibition, which culminated in ‘the Henson case’ (as David Marr coined it).

While Roslyn Oxley9 sent out an exhibition invitation with an image of a young nude Henson model, the limited-edition inkjet prints available this year at NGV avoid any sense of selling underage bodies. Instead, the Design Store sells a photograph of a quaint bay at twilight, Untitled (2008/09). This print embodies many typically Henson qualities, yet ensures that all nudity remains in halls purposed for the exhibition of art. In this vein, it is abundantly clear that the rearrangement of the level two galleries to host Henson’s work is no coincidence: for example, nudity warnings are now positioned at both entrances to the show.

2008 is also the year of the earliest photograph in the exhibition, even though Henson has been exhibiting at significant Australian and international institutions since 1975. This suggests that his artistic style and the scope of his exploration is unchanging, and perhaps therefore unchallenging. Indeed, challenges to artistic freedom are not entirely novel, and it would be remiss to forget the culture wars of the 1970s, or more recently, Paul Yore’s 2013 exhibition in Melbourne, Everything is F—-cked.

Exhibiting the same procedural artisanship, themes and creative objectives as ever, the show reveals Henson to be an artist who continues to rearticulate his own internationally recognised notions of artmaking. Perhaps this is unsurprising given that Henson’s success (he exhibited at the National Gallery of Victoria when he was just 19 years old, and has since been acquired internationally) is largely predicated on his distinct style.

While Eggleston, Croggon, and Coulter are in the level three galleries normally used for temporary shows, the spaces that house European painting and sculpture from the mid-19th to the 20th century serve as an intentional prelude to Henson’s show. I have been told that at the artist’s request, the permanent Salon display has been temporarily relocated to make room for his exhibition. The NGV agreed to have the Henson hall bookended by Modernist and European masters—perhaps unsurprising given that classical music so often accompanies television promotions of Henson’s work, in a recent ABC TV story this included Mahler, Allegri and Gorecki.

To reach Henson’s photographs, we pass impressionist landscapes, works by renowned European artists studying the human form through portraiture (including Pierre Renoir’s Jeune femme assise, décolleté (Young woman seated, with neck and shoulders uncovered), a Balthus oil painting of a young women Nu au chat (Nude with cat), and Robert Delaunay’s Nu à la lecture (Nude woman reading)). Immediately preceding the eastern entrance to Henson’s space, on the left is a tall marble sculpture of a nude Musidora (the stage name of beautiful 19th century actress known for her femme fatale persona), by Marshall Wood. On the right is an oil painting by Edward Burne-Jones of a trio of lovers inspired by (famously playful and erotic) Greek mythology. This positioning demonstrates that artistic meditations on corporeality, youthful beauty and sexuality reoccur throughout history, endorsing Henson’s irrefutable renown and highlighting the “eternal” values of his work.

In these works, nudity occurs in the way that Giorgio Agamben argues: with its biblical ties to the Garden of Eden, being without clothing was to be ‘clothed in grace’ and wearing human clothing was Adam and Eve’s punishment after the fall. Nakedness is thereby the theological counterpart to clothing rather than an uncovering. Even if we consider photography in this context as ethically laden, Agamben shows us that nudity is not degrading. In this way, Henson’s photographs do not carry the moral weight that is typically understood of photography. I return to the straightforward position that Henson’s nudity is not erotically charged or explicit. His models are simply without clothing. The NGV’s intention to place Henson among these works positions him as a favourite, skilfully continuing an art-making tradition not dissimilar to 19th and 20th century masters.

Henson’s photographs are well suited to this environment. In keeping with the aforementioned interstitial thematic, the subdued, atmospheric lighting of Henson’s space strongly juxtaposes the lighting ordinarily used to display European sculpture and oil paintings. His work reflects what is hung on either side of his hall, because his photographs pair reflections on the human figure with those of human-made and natural landscapes. I became uncannily aware of my own presence in the gallery, as the blurred faces and heads passing classical marble sculptures and oil paintings blend with those of visitors passing through the galleries surrounding Henson’s space; Henson’s audience becomes his subject, as does classical art history. Accordingly, the strength of the show is its self-conscious positioning within the NGV as whole, because it foregrounds the large extent to which Henson injects his work with meaning by setting himself against the backdrop of an artistic canon.

Aside from this, if we consider that he uses similar photographic techniques on his fully clothed and inanimate subjects that he does with his young models, it is easy to read his work as a ‘sensitive, sophisticated study of the human condition’ and to agree that ‘like much of Henson’s work, there is little that is explicit about these photographs’, as the wall text reads.

Yet the reactionary nature of the show’s positioning and the defensiveness of the wall text’s implicit counterargument (which abstains from ideologically charged debates relating to individual freedoms) dismisses and still somehow succeeds in reducing the validity of the initial controversy surrounding his work: that some audiences are uncomfortable with Henson’s fascination with adolescent sexuality, his use of young models, and the hermetic space of the photographer’s studio to realise this fascination.

Ultimately, Bill Henson leaves us with this question: is the artist’s unchanging style a paradoxical attempt at self-censorship? There is a sense that the exhibition is ‘in-between’ the artist’s reputation for shock and controversy, and the benign predictability of his unchanging style and subject matter. Henson is clearly comfortable as a well-established artist, continually supported by visual art institutions (which are perhaps comfortable with his self-association with high art, music and literature)—does this make him afraid of pushing the boundaries of contention too far (as he unwittingly did in 2008)? Whatever the case, the exhibition demonstrates that Henson’s prestige as an artist is unlikely to be undone, as if the opposition to his more challenging work was too shocking a debacle to repeat.

Beth Kearney studies Art History as well as French Language and Literature. She is undertaking a research Masters in Montréal from September 2017.

Title image: Bill Henson, Untitled 2009/10 2009-2010, inkjet print, 102.4 x 152.0 cm (image) 126.5 x 177.6 cm (printed image border) 127.1 x 184.6, cm (sheet), ed. 2/5, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Purchased, Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2012.)