In the Ruins I See the Future

Scott Mclatchie

An image of the snake eating its own tail, a symbol of repeating destruction and renewal, sets the tone amongst the warm glow of reds, golds, clay, dust, and stone for the current exhibition at Incinerator Gallery, curated by Jake Treacy. Above me as I enter In the Ruins I See the Future, I can see the elaborate portrait of an antique god and beside that the Ouroboros. A wall-text near the entrance explains: “The future is distilled through the icon of the Roman Deity Janus. Depicted above with two faces—one reflecting back on the past, as the other faces toward the future—he is the god of beginnings, transitions, passages, and endings.” I often reflect on the pilgrimage to Incinerator, an almost church-like building in Aberfeldie, with its high-sloped ceilings once filled with furnaces but now home to works by eight contemporary artists harbouring renewal and change. Here is an exhibition that seems to begin with this sense of return, even to see something new.

The upstairs space of Incinerator Gallery holds a tense heaviness that is removed from the echoes and reverberations of the downstairs space. As I enter, a chaotic ruin abounds in the landscape of the space, and like an opening to a cemetery we almost have to dance around the heavy matte of concrete structures installed by participating artist, Hugh Crowley. Works with a connection to queerness and the coded natures of objects; structures reminiscent of parks where looming trees, leaves, and matter would fill the spaces in darkness; in Crowley’s concrete structures lies an empty bowl within the construct of the concrete plinths. Here instead we have bleeding wooden tanbark and dirt staining the tombstone-like models and yellowing rain-water pools. The gallery is a graveyard. Viewers must carefully position themselves in a respectful reverence to these structures, where people may have been laid, but just who remains mysterious to those entering?

Like Crowley’s gates, Cruising Utopia (2022), also open onto the evolving soundscape and video work, Temples of Doom (2021), by Ryan Andrew Lee. In turn this work seems almost to respond to the movements of the opposing video work by Karina Utomo, Mortal Voice (2022). Their works engage a transformation, and in the droning I hear subtle hisses and whispers of Utomo’s work through the headphones hanging nearby on the wall.

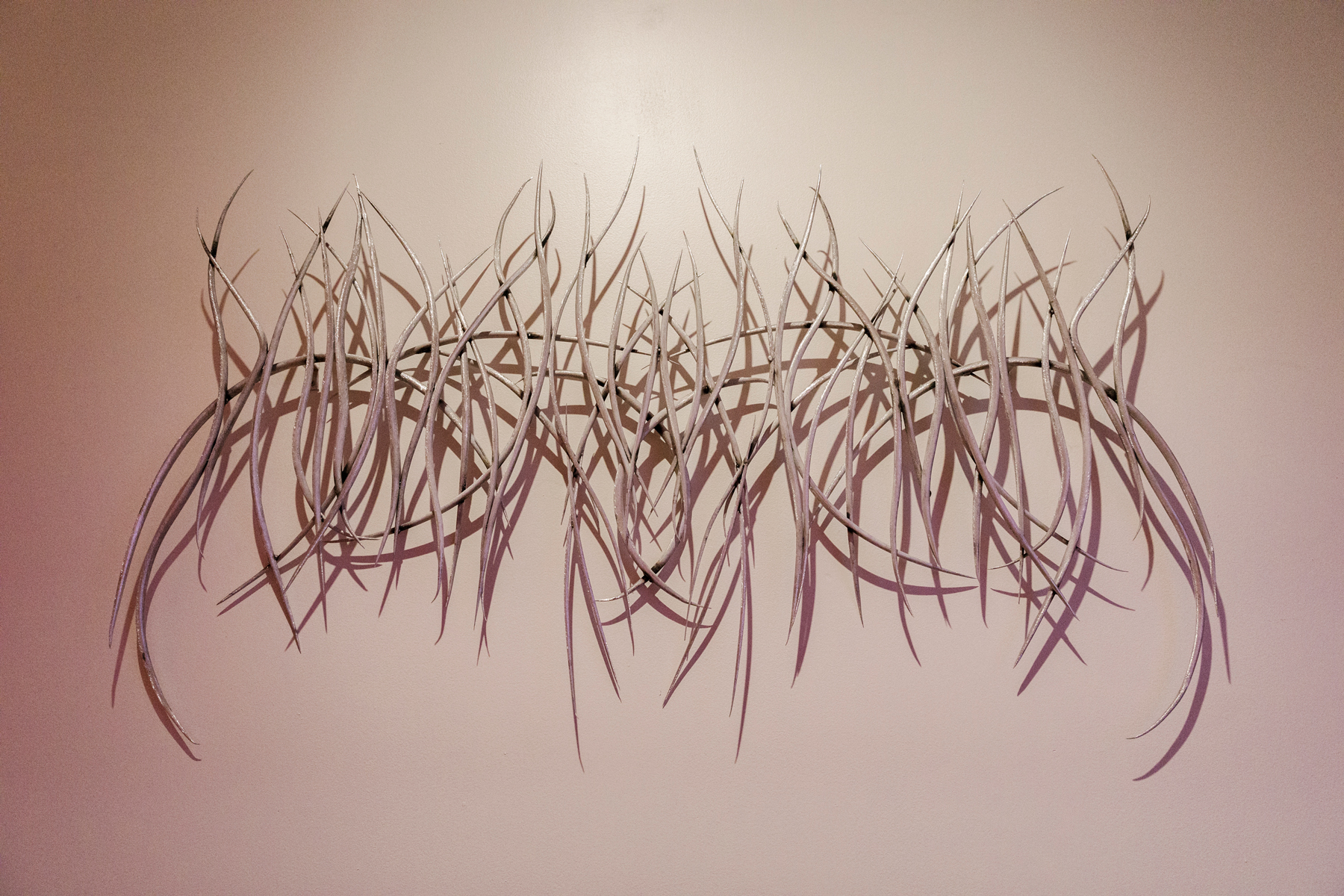

These sounds captured a special moment for me. Donning the headphones of Utomo’s Mortal Voice, I felt in awe as the space began to shapeshift from the complexity of the sounds. A sharp, Black metal inspired structure of welded aluminium, Utomo’s Darah/Tulang (2022)—meaning “blood/bone”—hangs illuminated on one wall, with protruding sharp edges. Despite the aluminium frame, it is heavy and fierce, unattainable. It appears almost as a warning of pain in the context of the work as well as visually referencing the metal music subculture’s obsession with organic language. Utomo’s involvement in extreme metal creates a cross-cultural practice with her work, with movements, sounds, and gestural expression within both metal and Javanese storytelling. The slow churning and evolving voices in Mortal Voice create a tensioned chaos that resolves within the power of the voice we hear, forever captured in a looped video, but changes within the context of the space as we hear it over time.

Treacy’s curation focuses on ideas surrounding an anarchistic concept of destruction and rebuilding on the shaky foundations of Western modernity. I find connections to nature and materials pertaining to this utopian ideal, however, one where we could be going if we work toward a future of caring for the lands and waters where we live, one that in spite of imminent collapse sees regrowth through both literal and conceptual navigation into the future. Returning to Ryan Andrew Lee’s Temples of Doom, the Sydney-based cinematographer focuses this work on the damage to culturally significant sites of Indigenous rock art by mining companies. It is a slow-building and-escalating video work, a sobering reminder of the continued disregard for sacred sites by successive governments and private companies for the sake of materials and profit. Even as uneasy viewing, the work also acts as a document of the names of the companies participating in this destruction.

The curation of the space, while referencing the ancient Egyptian iconography of a never-ending cycle of destruction and rebirth, also resembles the Ouroboros by design. Forcing visitors to navigate this circle of constantly shifting and changing materials, their alchemical form becomes soil, dust, and dirt, manifesting again into golden radiant beacons piercing the show’s red hue. Claire Bridge’s works are aglow in the light, the golden and glazed ceramics The Unfolding, Torus, and Petal Lotus (all 2022), sit atop a plinth with a resting bed of glittering black dust. The scaly texture of these golden stoneware bowls is reminiscent of the recurring theme throughout the exhibition filled with returns and renewals of the past and the present. The ceramics take on new forms in the process, and Bridge’s work adopts an approach fusing symbolic imagery and language, such as Indian, Tibetan and Sanskrit, rooted in her heritage, both Eastern and Western. Although I was somewhat intrigued by the mysterious description that Bridge provides in the wall text, these sculptures affirm renewal from the literal ground up to take on new forms.

Within the implied circular shape of the exhibition, I eventually found myself sitting face to face with the humanoid figure petrified in place, behind it a large obelisk leering with its fierce and hostile branching out. Below it, the glow of a cold blue light emanating from within the tombstones supporting the structure, is a small murder of crows atop watching the beast with its face made of twisted branches and twigs. Michael Needham’s two monolithic works, Through the Pines (Cryptal Reverb) (2018) and Gnasher Mongrel (Nietzschean Demon) (2019), embody an uncanny familiarity and extend the narrative to kings from the biblical canon, relating them to the corrupt figures of today. Perhaps they are national leaders, relating to the work by Ryan Andrew Lee in their allegiance to companies who capitalise on destroying the planet. In my view, the beast that descends into madness and destroys all in its path lives in a contemporary setting and the grim obelisk speaks of colonisers within Australia and colonisers around the world.

Hung beside these sculptures, three square-framed prints sit adjacent in imaginings of occult practices, bodies, and fabrics, strewn together as if conjoined in a unified sheet. A harsh, bright flash captures an almost candid moment of a ritual in Joseph Häxan’s intimate yet chaotic digitally-altered photographs. Witches, as described by the wall text of Häxan’s work, are the figures who bring havoc and hysteria on society, uproot the status quo, and disrupt the norms of a society full of corruption and destruction. These acts of wild fervour in Apocalypso (2019) remind me of Gustave Dore’s beautiful nineteenth-century etching Satan Descends upon the Earth (1866). In the central work, Blood (2018), we are met by the gaze of two figures bathed in blood seemingly connected at the torso. In the frame next to it a multitude of bodies lie in an almost euphoric heaving of flesh toward the night sky. In Space The Stars Are No Nearer (2018) is described by the wall-text for Häxan’s work as “an image of the rapture”. The departure of the flesh into a transcendent form into something other, it is finally intangible. This being the act of transformation of flesh, blood, and bone.

All elements of the human body are seen within this exhibition, but so is the red heat of fire, which I see reappear in nearly all of the works on display. It is sometimes quite literal in interpretation, but plays within a conceptual nature. Whether it is building or dismantling, there is a constant duality. The fragility of organic and wrought materials such as copper and ceramics are the continuum of flesh and bone. It all feels breakable, yet we cannot be destructive in a space meant for creativity, and I feel the palpable sense as a viewer held accountable for the space. This may be interpreted as a control mechanism, of not being able to act out in the space but to remain a witness of these acts of destruction and rebirth.

Back outside the cemetery gates curiously made of candle-wax, we are greeted with a taunting silhouette of a rich red standing in the maw of a cliff face opening. A naked figure stands powerfully, while the surrounding images, nailed into the wall, dance and shift in a spirit of and connection to country. The Broome-based photographer Michael Jalaru Torres’s rich red images in Mother Earth Burn (2019), a series of four images arranged by piercing nails into the wall, depict twisting figures which match elements of the surrounding works, evoking a sense of incredibly powerful and unstoppable strength. The figures are unwavering in their stoicism most evident in the largest image in the exhibition, Torres’s Blood Flows over Falling Stone (2019). The concepts of Mother Earth and the indigenous knowledge of caring for country manifest in this deeply connected use of red casting on the photographs, which appear as both earthen soil and blood.

Below Jalaru Torres’s figures on the wall lies a body of soil, glowing in that same red that covers the rest of the exhibition. A lone crown in The King of Nothingness (2022) floats above, as if for an audience member to take its place, making up the heavy space for Adina Kraus’s collection of disintegrated and dismantled sculptural installation work situated in the centre of the room. Etched symbols of the Tree of Life on clay tablets immersed in the soil, materials of terracotta, copper, bronze, and mud lay bare in their own destruction, waiting to be rebuilt. Kraus’s In Story, Song and Stone and I Am What I Am (2022) also embody the continued theme of renewal, quite literally from the ground up. This work suggests the point that humans are their own gods: made in god’s image but embodying an element of the occult within the structure of the world and the horror vacui of the void found within that we must fill.

Several days after my initial visit, I returned to the exhibition for a performance of Mortal Voice by Utomo, a fitting end to my experience of the glowing red space of In the Ruins I See the Future. Immersed in deep red light, the space’s circular form was upset by chairs for our experience of Utomo’s powerful voice. In the span of a twenty-minute performance, Utomo responded to a simulacrum of herself on the screen, with subtle voicings of the slowed down video and audio acting as groundwork for the presence of Utomo’s real self, who hissed, groaned, and snarled at her digital self, moving in a continuous loop. What I didn’t expect was a feeling of catharsis at the end of the performance: the hair on my skin stood up when Utomo’s voice would rise into a powerful belting yell. This supremely moving act of strength through voice ends with peace that I took with me, feeling through the witnessing of this performance a sense of completion for myself.

Scott Mclatchie (they/them) is a multidisciplinary artist and musician from Naarm. Scott explores the dystopian in their own work as well as trying to explore the fringes of music by performing with an array of bands and projects. Scott is currently studying a Masters of Curatorship at Melbourne University.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of Meridian Sculpture.