I will never run out of lies nor love

Victoria Perin and Brendan Casey

π.o.—Melbourne's preeminent anarchist/poet/DIY art historian—has observed a deep gulf between literature and the visual arts in Australia and speculates that Ern Malley is to blame. Before Ern, so the argument goes, art and letters co-existed in a collaborative landscape, evidenced in no small part by Angry Penguins the wartime journal that printed Ern's hoax poems in 1944, and thus ground zero for the rift. Thumbing through the magazine's pages, a reader was as likely to encounter the reproductions of an artist who also wrote poetry, such as Sidney Nolan or Joy Hester, as a critical text or poem by Max Harris or Geoffrey Dutton. And so, when Angry Penguins published Ern's faux-poems, concocted by James McAuley and Harold Stewart one drunken afternoon with the aim of exposing the magazine's modernist excesses, the hoax embarrassed painters and writers alike. Friendships soured, commentators grew apprehensive, and a wedge was driven between poetry and the visual arts.

Practitioners attracted to both the gallery wall and the page have rarely been deterred, but (according to π) they have lacked a critical discourse that might support their practice. In looking for a tradition through which to approach the artworks in I will never run out of lies or love, an exhibition currently on display at Bus Projects, we might look no further than to someone like π.o., whose vital dialect poems (among much, much more) are a trailblazing example of ethnic minority writing in Australia. As the curators of I will never…, Nanette Orly and Sebastian Henry-Jones write: “The use of language within artmaking is a powerful tool to negotiate identity through social, political and personal narratives, as it provides agency over (the artist's) message”.

Accordingly, I will never… is an exhibition about 'language' rather than 'text', the performance given privilege over the sign. There is no text in Rosie Isaac's Spit trap I, II or III (2019), just glass tubes, which at first glance look like unlit neon tubes, but in fact are—surprise!—vessels filled part-way with spit. The abject horror of this discovery lingers: a vivid illustration of the mechanics of speech, the tubing traps the lubrication for words, a clear 'grease' for the tongue and throat.

The remaining works of I will never… emerge from a broad and varied range of linguistic traditions: from Thai calligraphy to confessional poetry, SMS shorthand to ritual incantation. EJ Son has inscribed small lettering on her witty ceramics. Korean characters are either engraved or glazed onto porcelain sculptures, cast to resemble rocks, or hand-built figures with hard humorous dicks, bunny-tails and/or shit for heads. The text reads (in the artist's translation): “ugly duckling”, “to be hammered down”, and “hooray for self-reflection”. Son's rocks are glazed in a way that makes the text appear precious and tactile. Glaze has seeped into the incised words, and the artist has wiped it away to make it easier to read, but also to make it resemble a found, ancient artefact, worn down by generations of gallery visitors. Maybe you're touched by this rock that seems polished by human hands, until you read it or its translation, “so yeah the rough rock blah blah blah 'soong goori dang soong dang dang' keep walking”, more immediately recalling 'zaum' sound poetry than a profound relic.

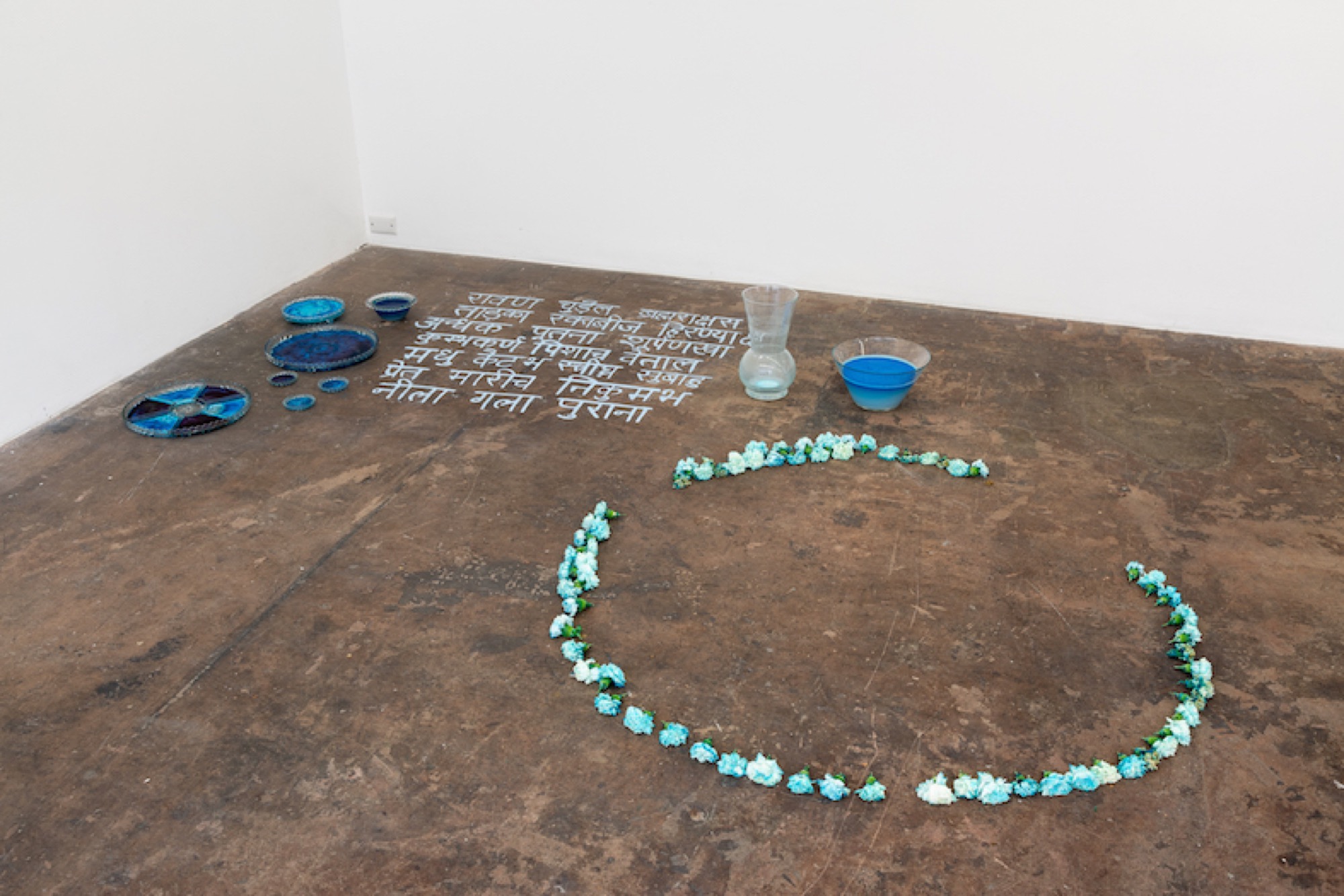

A performance on the opening night activated Manisha Anjali's work Old blue throat (2019). On the floor is a blue chalk inscription of demon names in ancient Vedic Sanskrit, a language the artist does not read. Surrounding the text we find the remnants of the ritual: vessels of blue liquid, some that have dried in various hues of blue residue, and a circle of white carnations, blue-tipped with absorbed pigment. Anjali's instructions for participation hum with the poetry of incantatory text:

1 - Enter the Dream Realm.

2 - Pick Blue Flower from Bed of Blue After Life Flowers.

3 - Leave Halāhala by the door.

4 - Give Blue Flower to (your) Demon.

The work alludes to halāhala, a deadly blue poison and by-product of the recipe for Amrita (the nectar of immortality), emitted during the churning of the ocean of milk. According to Hindu scripture, Lord Shiva was stopped from imbibing toxic halāhala by his wife, Parvati, who gripped his throat and prevented him from swallowing.

What does this diasporic ritual have in common with Natasha Matila-Smith's fabric works, with their aphoristic stencils on plain calico? Matila-Smith's Love-letter (2019) is less an example of text-art than txt-art, its stencilled phrases recalling a series of txt messages sent to an ex-lover in order to make them feel bad: “I cried so much I ran out of tears”, “I held your hand through a lot”, “I learned to be guarded and now I have intimacy issues you dick”. Her textile (txt-tile), sewn and hung to resemble a fake installation wall, includes tongue-in-cheek remorse—”Sorry for being so emo”—but it is a false apology. Like Anjali's Old blue throat, Love-letter is a work about finding words to confront your 'demon', a series of txts sent to expel poison and bile.

Angie Pai's two-part work is almost too exhausted to speak. Crawling on all fours—in a video filmed by the artist's mother—Pai wears the thermal shirt of her late ah gong (grandfather) as she edges around a wet suburban Melbourne street. Pai has embroidered columns of text in raised raw silk thread on this shirt, another undershirt, and a handkerchief. You can't see the text in the film, but the off-white garments hang in the gallery just above your head. The video enacting a mourning ritual and is almost too tender, but the hand-embroidered text is arresting. The artist noted on an Instagram post: “speaking to grandpa as I vandalise his clothes …” The complicated grief of the grandchild comes out slow, laboured and in text like scarring.

In the exhibition catalogue we read: “A bad story may be called untruthful. Language performed in I will never run out of lies nor love is more truthful for its effect than as fact.” Truthful expression is important to the curatorial framing of the exhibition. The curators are at pains to emphasise language as testimony: “language in this exhibition is used to make tangible that which often goes unread, unheard and unknown.” This is an exhibition firmly grounded in the contemporary politics of identity, and the revelation of the 'authentic' self.

Yet to return to Angry Penguins at the risk of reopening old wounds that rend art from literature—we might remember the many masks of Ern Malley. Ern 'was', of course, an 'outsider' artist, an unsung worker (a car mechanic, an insurance salesman, and a watch repairman); an émigré (he came to Australia from Liverpool as a child); and chronically ill (Ern suffered Graves' disease, leading to his early death aged 25). He was written by two poet-soldiers, McAuley and Stewart, who also invented Ern's sister, Ethel, and cross-dressed as her in letters. (The “brilliant” housewife figure of Ethel, writes Michael Heyward, “anticipated by a decade that formidable icon of Australian suburban sensibility, Edna Everage”). Meanwhile, later in life, Stewart would come out as gay. In the end, this complex play between identity and mask is perhaps the inheritance of artist-poets working in Australia: a fertile landscape which exists somewhere between fact and fiction. It seems to us that the artists in this exhibition brandish more masks than the catalogue gives them credit for. Art history and criticism, which has failed to serve artist-poets in the past, must learn to love the lie.

Brendan Casey is a PhD student living in Melbourne. His essays and criticism have appeared in Meanjin and Difficult Fun.

Victoria is a PhD student at the University of Melbourne. Her research concerns printmaking in Melbourne during the 1950s, 60s and 70s. In 2013, she was the Gordon Darling Intern in the Australian Prints and Drawings Department at the National Gallery of Australia.