Hito Steyerl: Factory of the Sun

Amelia Winata

Hito Steyerl is arguably the most important “post-internet” artist alive today. Though the history of post-internet art is a nascent one insofar as wide-spread use of the technology is quite a recent phenomenon, the art that responds to it also reflects this ascendency. Ironically, the post-internet 'condition' seems to have had a limited lifespan, the work seeming to confirm the zeitgeist of the recent past—one that has quickly evolved into an altogether different present.

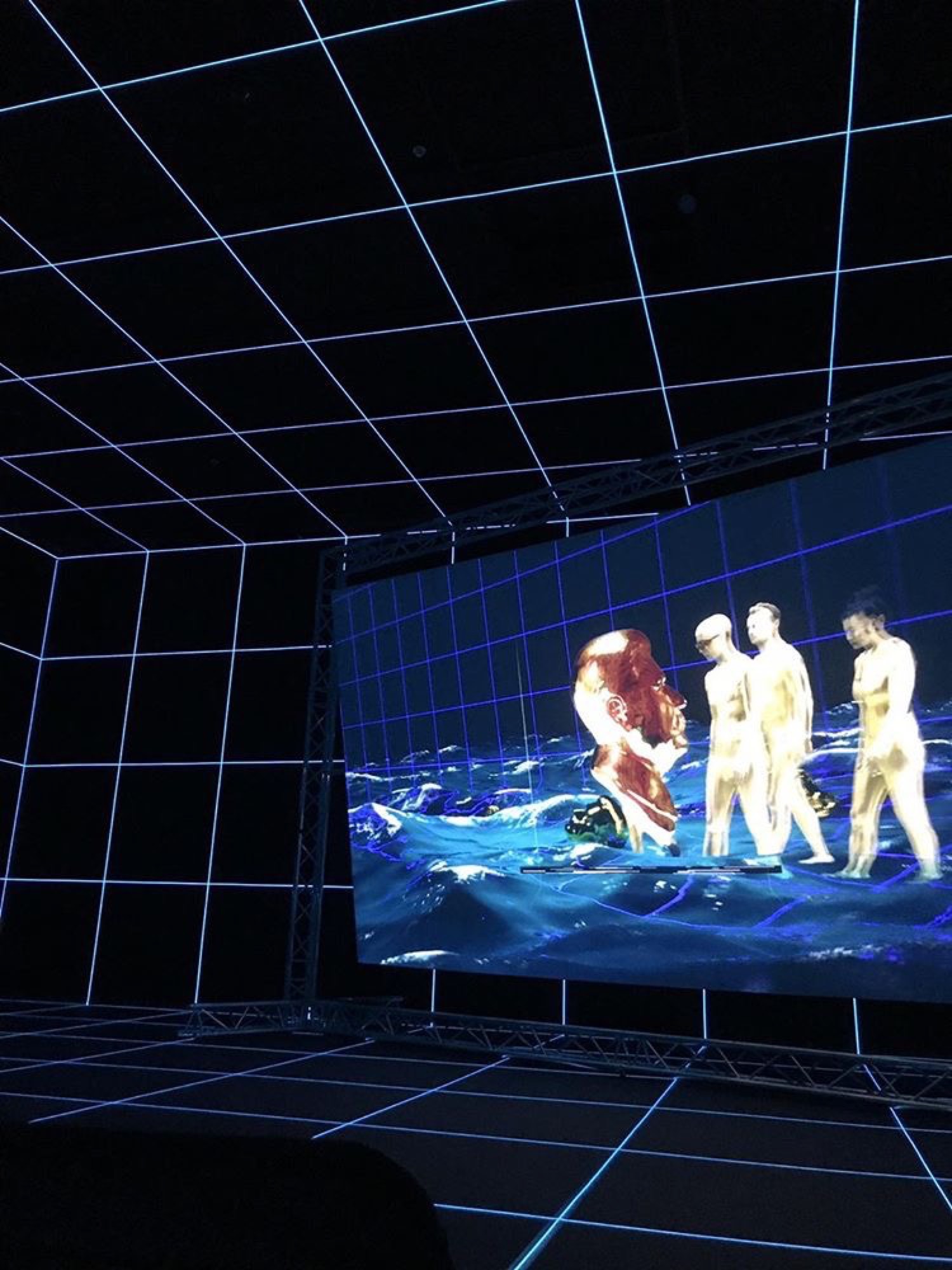

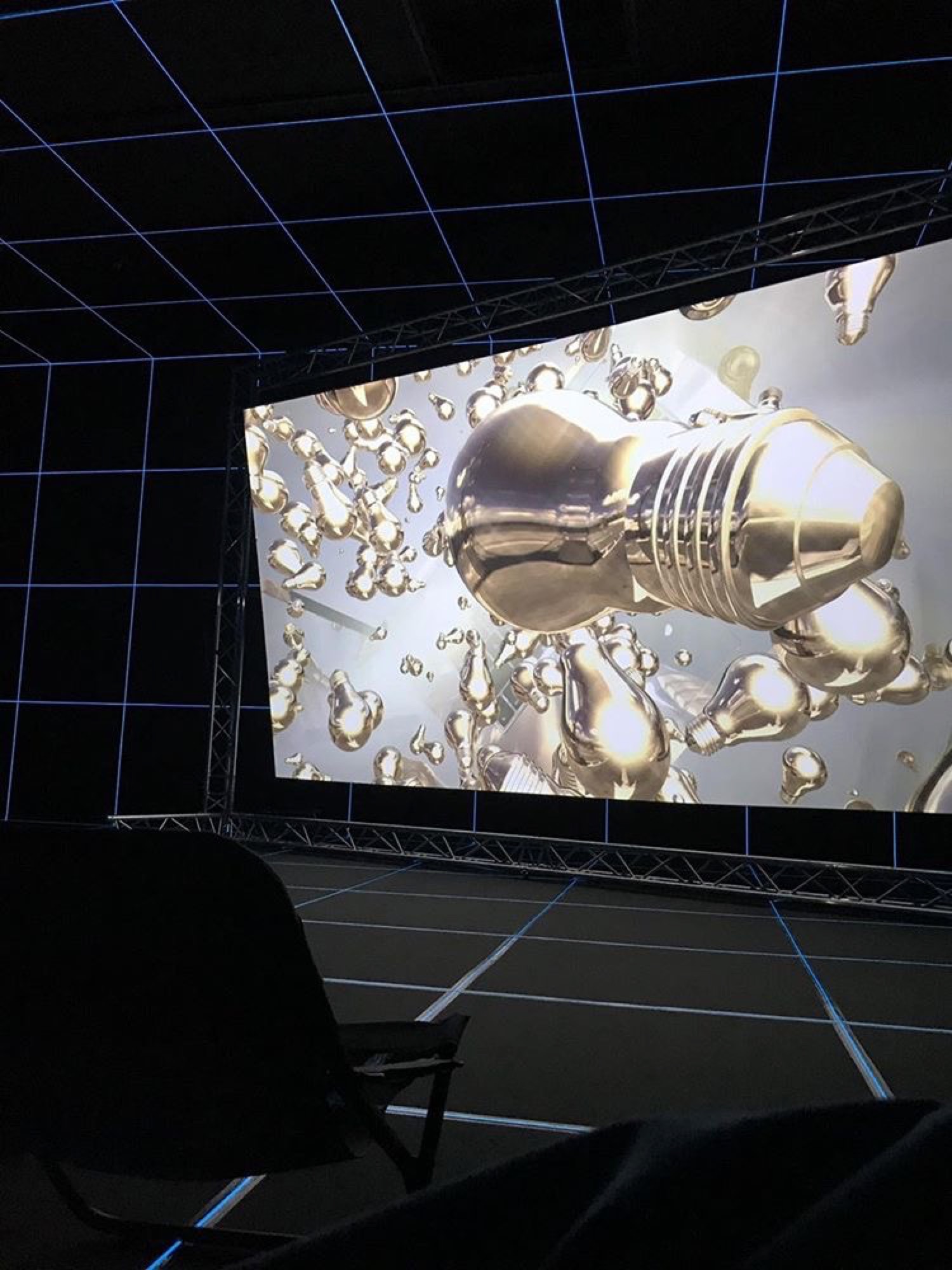

Factory of the Sun, 2015, was first exhibited in the German Pavilion of the 2015 Venice Biennale, All the Worlds Futures. It is a 21-minute single-channel video presented on an enormous screen supported by stage mounted scaffolding. Upon entering the exhibition space, the viewer is overwhelmed by a dark room gridded with neon blue light tubes that create a matrix across the floor, walls and ceiling like an '80s video-game or '00s remake. Plastic reclining chairs (the smell of which trigger olfactory memories of IKEA) lined up across the back of the room encourage the viewer to stay for the duration of the video. I must admit that I found the experience of watching Factory of the Sun entertaining. It felt like a theme park ride—Baudrillard's theme park, of course. The sudden display of the work after its 2016 purchase is surely also a reaction to the ongoing public demands for the NGV to exhibit more female artists (or at least fewer male artists). Symptomatic of this is also the concurrent solo exhibition of works from the Guerrilla Girls.

The work is a bizarre mash up of scenes that form a loose narrative about the death of a person as a result of the Deutsche Bank attempting to accelerate the speed of light. Anybody familiar with Steyerl's work will instantly recognise her erratic use digital imagery and references. Some of the myriad depicted subject include drones, “internet dancing” (one presumes this is the phenomenon of people posting videos of themselves dancing on online platforms such as YouTube), the relic of the Teufelsberg spy base in Berlin, popular uprisings, human migration and video games.

The storyline is loosely based around broad concepts of information exchange in the digital age, the migration of populations, mega corporations, and the general postmodern “mood” of irony or solemnity that seems to now go hand in hand with the critique of the neo-liberal. This final point, the irony/solemnity bind, is one that is represented by way of visual juxtapositions in the video. For instance, A group of dancers in gold one-pieces— representatives of the dystopian future—perform atop the Teufelsberg ruins, as though anachronistically existing in an expanded present.

The irony of Steyerl's practice is that it relies upon readily available, easily transferrable imagery that, in theory, should operate across time. Think, in particular, about stock imagery and the way that it is relied upon to communicate across language barriers quickly and effectively and can be relied upon to survive only because it resists fashion and adapts as necessary, evolving from its original form to fit particular context it is required to exist in. It is also a topic that Steyerl addresses in her 2009 essay In Defence of the Poor Image. She writes there:

Steyerl implies that the poor image is a democratic image. What's more, she presents the concept of the internet as democratising because in this idea is also embedded her implication about the poor image. In Factory of the Sun, the viewer is offered masses of such images that riff off of 90s video game graphics or early 2000s science fiction style animations, for instance. These are consciously dated images. As a colleague noted, such 'retro' imagery is also on trend at the moment—think Bladerunner 2049 or Stranger Things. Others, though, such as the gold body-suit clad dancers perched on the Teufelsberg rooftop—obviously inserted digitally but with the effect that these individuals could easily have been there—just look a bit old. I suspect that this is because, in the three years since 2015, we have seen similar imagery produced by a plethora of other artists.

As is the case with most hot new things, Steyerl has sadly been somewhat the creator of her own demise (though maybe demise is too strong a word) insofar as her immense popularity and presence amongst young artists saw a proliferation of work in a similar vein to her own. In the years following Steyerl's sudden popularity, many artists embraced the thematic of the post-internet—a term that in itself now seems quite daggy. Typical Australian examples might include Marian Tubbs or Hamishi Farrah. While internationally Petra Cortright and Ryan Trecartin are representatives of the style next to Steyerl—though the latter were producing work contemporaneously to her.

Of course, the internet and its all encompassing nature was always going to be a hot topic for artists. In the first decade of the century, theorists, artists, writers and curators were speculating about the hidden impacts—be they positive or negative—of the internet. This took many forms. For documenta XI (2002), for instance, Okwui Enwezor curated such a huge volume of digital video that it was estimated it would take 600 hours to watch it all—25 consecutive days. Fast forward, and in 2014 a survey-like exhibition entitled Art Post-Internet was shown at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing and featured the likes of Steyerl alongside other post-internet staples such as Cortright and Jon Rafman. The question therefore arises as to where you go after a “trend” that's risen so quickly, peaked and had apparent retrospectives within the space of little more than a decade?

It's as if post-internet art already needs to be treated as a historical moment. A quick Google Search tells me that the installation of Factory of the Sun (purchased by the NGV in 2016) is virtually a carbon copy of the other iterations of the work that have been exhibited globally, including at MOCA and Kunsthal Charlottenborg. All of the installations have included the exact set up of retro Tron-like neon grid that spans the floor, walls and ceiling, as well as the reclining chair set-up and stage scaffolding. No doubt this is part of the contract that the NGV has with the artist. But I can't help but recall another installation of Steyerl's work at the 2017 Münster Skulptur Projekte—HellYeahWeFuckDie—that was installed in a decrepit modernist office building. Here the slightly dated quality of what was once sparkling and new was embraced as part of the natural process of things rather than ignored.

One final thought: while this work speaks to “democracy,” it is difficult to ignore that buried within this is also a notion of class, caught in a tension between the idea of the displaced and that of the cosmopolitan. Only those privileged enough to be a certain kind of “people of the world” are likely to enjoy the irony of the video, the tongue in cheek use of imagery to poke fun at the neo-liberal corporation, for instance. On the other hand, a diaspora, as opposed to a cosmopolitan, is a group of forcefully displaced human beings. This is a thematic in the video, as the main character, Yulia (a cyborg-type), provides a voiceover that discusses her Jewish family's forced exile from Russia. So the video addresses disenfranchised people, but only to always fall back on the tongue in cheek material that makes up Steyerl's practice. In fact, Steyerl work creates confusion precisely on what her position is. Is she simply ironic? Does Steyerl truly believe the internet will change the world for the good? Or is there a deeper-seated sense of unsettlement to her work?

The work does well to tell us as much about our current moment as it does about the moment it was created in—a moment so recent but that somehow already feels distant. In three years, things have changed. In short, a certain sense of the absolute unremarkable impact of the internet as it was lauded by post-internet art. Today, post-internet has become post-truth. Returning to Steyerl's provocation about the poor image—”it is about reality”—it is impossible not to look at this highly stylised video and wonder how this is a true depiction of reality. Though, I suspect that in 2015 it was a quasi-projection of a future possible world—albeit embellished. If the strength of Factory of the Sun is as an index of the recent history of humans coming to terms with our co-habitation with the online world, then its significance is as a historical work of art rather than one that is representative of now.

Amelia is a Melbourne-based arts writer and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne.