Hiroshi Sugimoto, Palais Garnier, Paris, gelatin silver print, 2019, installation view, Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024. Image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine

Elisa deCourcy

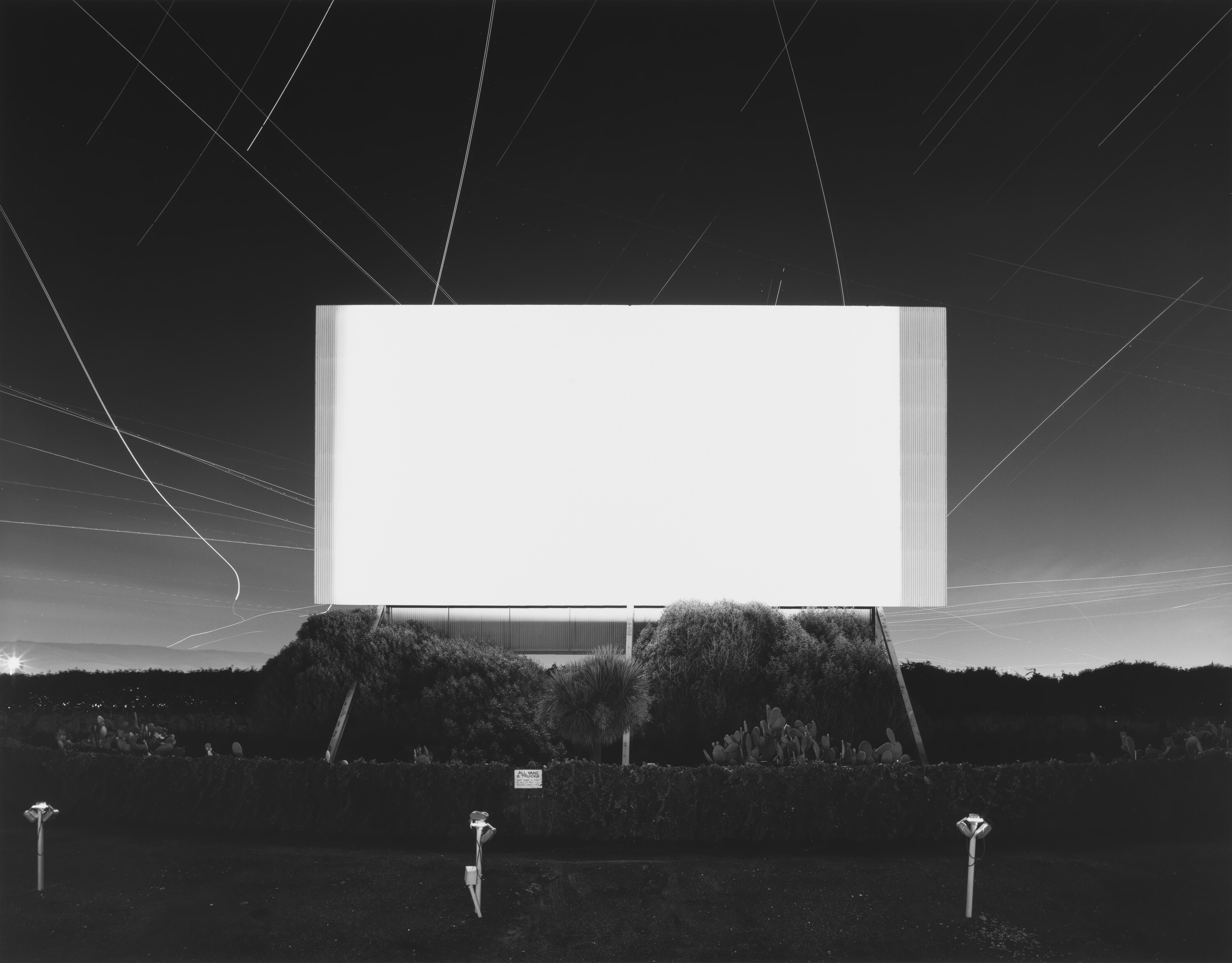

Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs compel us to look and then look again. His “wild” beasts, intimate portraits, sea-encased horizons, and ostensibly empty theatres are as striking as they are strange. Sugimoto’s work is concerned with the elemental properties of photography: light, chemistry, atmosphere, and form put to performative use. As the exhibition’s title implies, time is perhaps the only unifying concept that links eleven very distinct bodies of work drawn from a practice that spans over five decades. For Sugimoto, time is not simply something to be stilled—the photograph is not a straightforward Barthian vessel of “that-(which)-has-been.” Time is a quality he concertinas, elongates, and folds back on itself, toying with the medium’s limits.

We enter the exhibition at the top of a long corridor. Down the opposite end is a single photograph of a glowing cinema screen in a dark interior. We are immediately positioned as Sugimoto’s audience, suspended within a mise en abyme set up by the image’s own lit position at the end of the somewhat darkened hallway (at least this is how it appears from an entryway vantage). The survey of Sugimoto’s career is curated across adjacent and interconnecting rooms off this main arterial hall. If you follow this path, a progression that broadly unfurls Sugimoto’s work chronologically, then it is some time before you re-encounter this photograph and the Theatres series to which it belongs.

Like any artist, Sugimoto courts his audience’s attention. He piques our curiosity with intriguing compositions and rich tonal prints. But the more attention you give each work the more the subject matter unravels to betray an illusion. This system of revelation and reward is established from the outset. Lining the walls in the first room are large 119 x 149 centimetre and 119 x 185 centimetre monochrome prints of a condor, Colobus monkeys, a manatee, and a polar bear, all respectively enveloped in their habitats. Standing six paces back, a required distance to take in each frame, the perception that we are looking at wildlife photography holds momentarily. It is strange, though, how none of the animals are conscious of the photographer’s intimate proximity. Moving forward, closer to each work, the illusion starts to “crack.” There is something artificial about the perfect pyramid of raking light shrouding the manatee mother and her calf. In a similar manner, the monkeys’ tree-top ecosystem shifts dramatically in the mid-ground from lush forest to comparatively paler rolling hills. And the ice shelf upon which the polar bear has winched a seal carcass has a polystyrene-like gradient. The piercing clarity generated by each of Sugimoto’s twenty-minute exposures of museum displays—dioramas—register the detail of each taxidermied feather and fibre while, on close inspection, illuminating the artifice of the dioramas’ painted backdrops and synthetic staging.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Polar Bear, gelatin silver print, 1976, installation view, Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024. Image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley

Sugimoto began this series early in his career during the mid-1970s, at the American Museum of Natural History, New York, shortly after completing his studies at Art Center College of Design, Los Angeles. It was shot, as much of his work is, with his large-format view camera. This device was more commonly used (as the name suggests) for late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century landscape photography—the artist is deeply committed to illusion both technically and visually.

Sugimoto’s work also comments on the history of photography, more generally. One of photography’s French inventors, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, began his artistic career manufacturing dioramas in a studio from which he would later take a now-notable early photograph, Boulevard du Temple (1838). But Sugimoto’s Diorama series is not just a nod to a photographic (or museological) past. It is impossible to conclude whether his photographed beasts are fixed in time or temporally unmoored. Certainly, they appear to meet us at once as an ecological vestige, imaginative apparitions, and a prophetic warning.

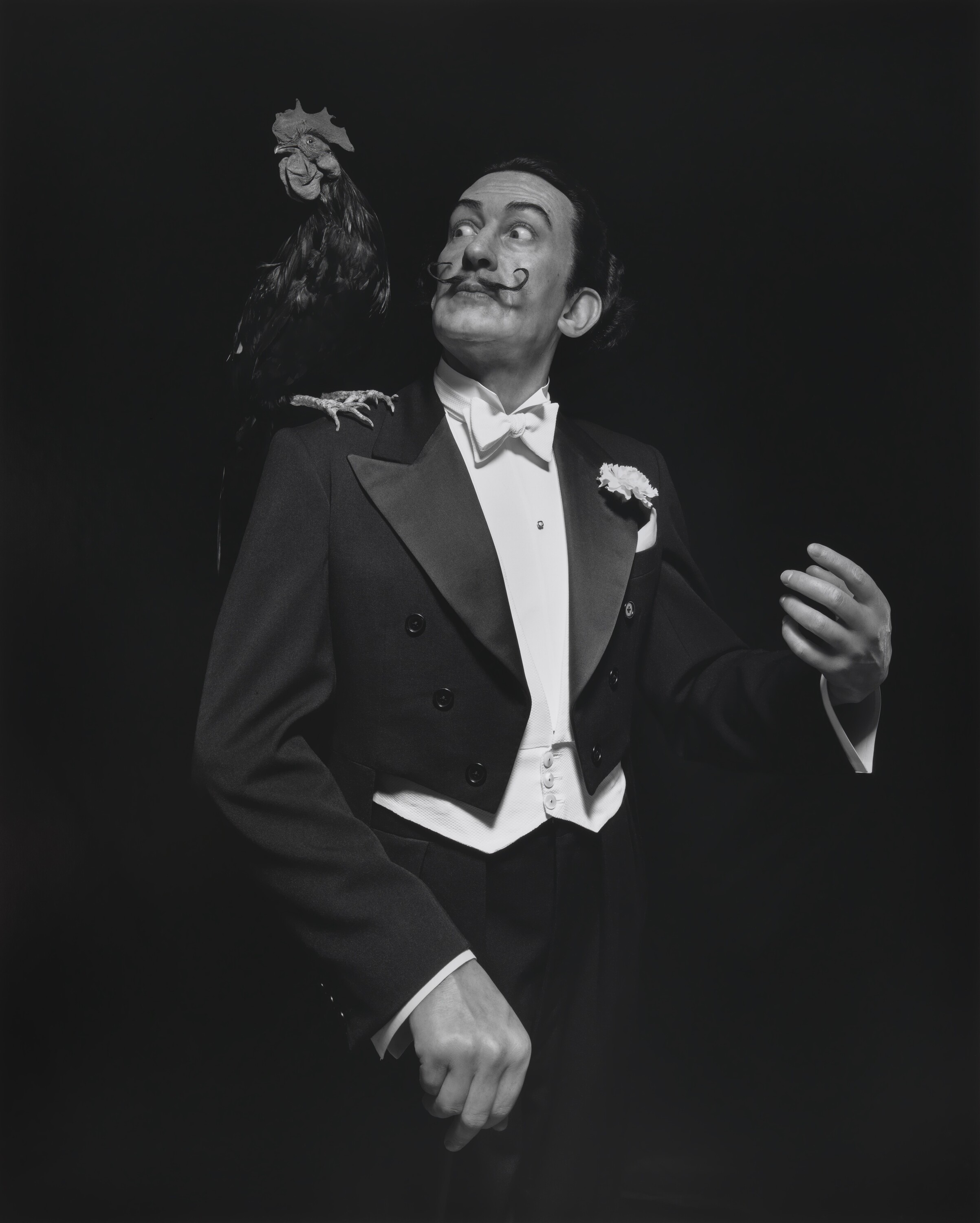

The winding footprint of the exhibition offers a lesson in looking playfully and poignantly delivered. The MCA is the second venue to stage this survey, following its first show at the Hayward Gallery, London in late 2023. In the accompanying catalogue, lead curator (and Hayward Director) Ralph Rugoff wrote that Sugimoto is a “poet of paradox.” The layers of ambiguity in the artist’s work, though, are generated through more than an engagement with a history and practice of photography. As Lara Strongman (MCA Director, Curatorial & Digital) notes in her own essay, the Portrait series of Madame Tussaud wax models recalls the dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio and Rembrandt. Anne Boleyn, Salvador Dali (with rooster on shoulder), Oscar Wilde, and Princess Diana, among others, seem to be emerging from the pure darkness of their backdrops. The subjects’ faces are bathed in the light, but as we look to the portraits’ edges the blemish-free and veinless skin of hands, for example, allude to the wax substrate.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Salvador Dali, 1999, gelatin silver print, image courtesy and © Hiroshi Sugimoto

When I was in this room, a fellow visitor commented to me that this work was “spooky.” I have been thinking about the meaning this word contains. I think she was using it to express how in Sugimoto’s portraits we encounter life and death in equal and opposing measure (all his subjects died tragically but are reinvigorated with a simulacrum of life through his lens). This threshold between life and death is further explored in his panoramic tapestry Sea of Buddha (1995), photographed at Sanjūsangen-dō temple, Kyoto. It shows in gridded symmetry a physical representation of the one-thousand bodhisattvas said to greet devotees at the gates to Paradise. Further into the exhibition, the softly rendered featureless horizons of Sugimoto’s Seascape series endow these views simultaneously with a generic vacancy and primordial latency.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Seascape series installation view, Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024. Image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley

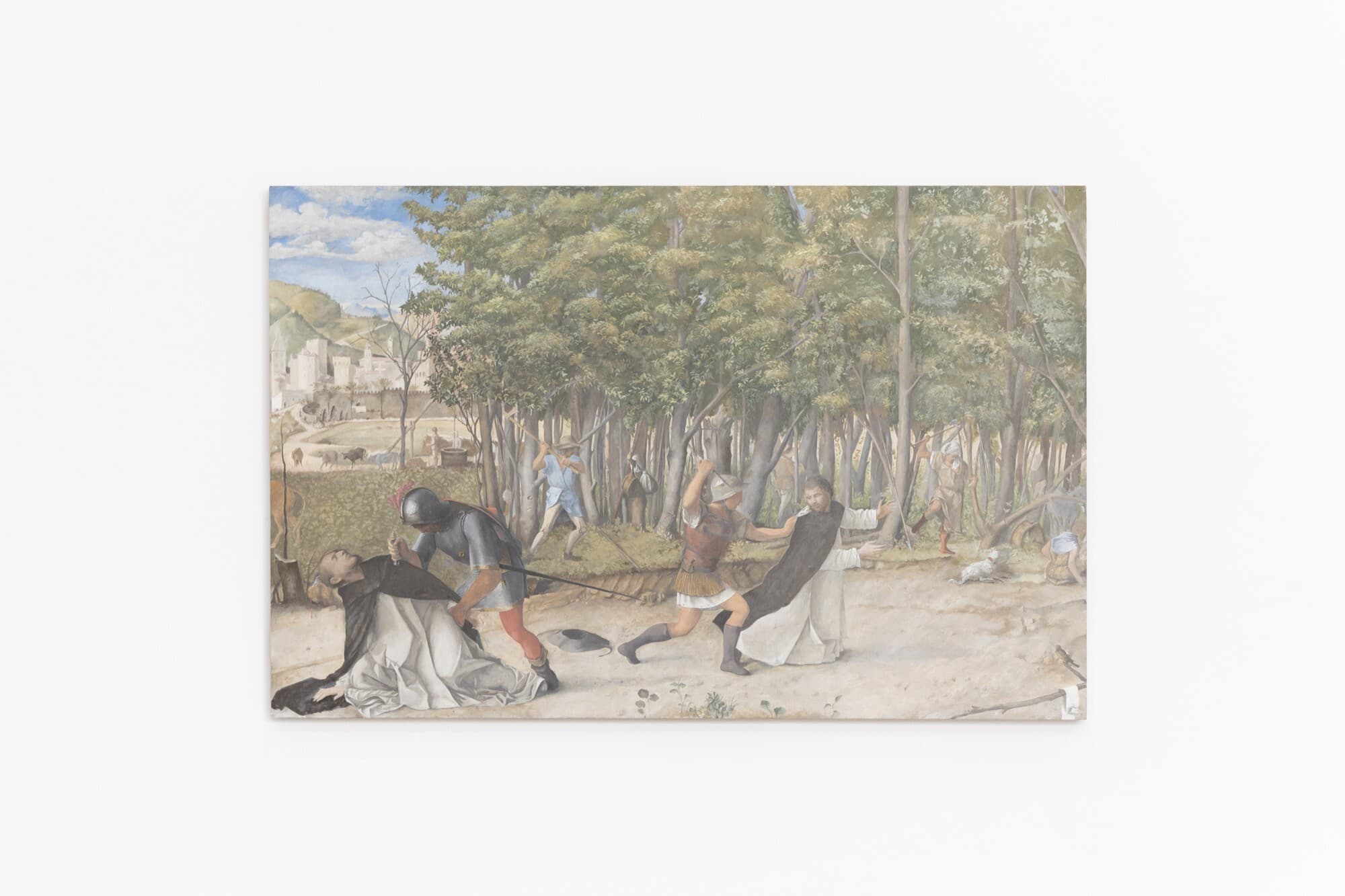

As we come up close to the Theatre series, halfway through the exhibition, a further shift occurs. Light transitions from being a technical tool to also becoming a primary subject. It is a shame that this important series is a little crowded in a narrow room. Sugimoto’s clear luminous screens are, on average, 172,800 after-images. Put more simply, they are the compression of the whole film into a single, long exposure. The resulting overexposed “blank” screens themselves function as something of an aperture. They push light onto the Art Deco fixtures of cinemas, the crumbling interiors of derelict theatres, and the manicured hedges and stilled playground equipment in the foreground of Drive-Ins. Greek actors frolic with Versailles ladies in an anachronistic garden landscape of the wall and ceiling paintwork of Cabot Street Cinema, Massachusetts (1979). Beams of light mark the path of planes that have flown overhead during the film at Union City Drive-In, Union City (1993). Sugimoto really wants to highlight the passage of time here, so much so that Metropolitan Opera House, Philadelphia (2015) is hung in a lead frame that is tarnishing (oxidising) as air is pushed through the gallery by the jostle of visitors’ bodies. This work is still coming into being even as we look upon it.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Union City Drive-in, Union City, 1993, gelatin silver print, image courtesy and © Hiroshi Sugimoto

In contrast, the subject matter of a following body of work, Lightning Fields, is captured in a crafted instant. Normally, lightning becomes visible when it connects with the earth, but Sugimoto’s violent gashes hang suspended on his photographic paper. As Geoffrey Batchen recounts in his catalogue essay, Sugimoto’s “fields” are less topographical, and their illumination is not metrological, but generated through an electric charge in his darkroom’s water-ladened developing tray. We can think of this series as being in conversation with nineteenth-century scientific experimentation (indeed, Sugimoto used English polymath and photographic inventor William Henry Fox Talbot’s Electrostatic Discharge Wand to complete early prototypes and studies for this series). But, as ever, Sugimoto is not rehashing or re-photographing, but taking the experiment to its nth degree. The works in Lightning Fields are forged with a vividness and voltage unrealised in the historic experimentation. These photographs are literally black and white, absent of midtones, and as such represent an extreme even within Sugimoto’s own largely monochromatic practice.

As we loop toward the end of the exhibition, the series Opticks feels like the show’s natural culmination, even though it occupies the penultimate room. These are the only photographs in colour and are among Sugimoto’s most recent work. Yet, the series’ primary field of enquiry is not pigment but, once again, light. It was inspired by Isaac Newton’s 1704 treatise of the same name, which concluded that light was not colourless but comprised of a spectrum of colours. In his own Tokyo apartment, Sugimoto restaged Newton’s experiments shooting a single ray of light at various angles through a glass prism. He photographed the resulting refractions cast on his wall with Polaroid film. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe identified seven prismatically-produced colours in 1810 following on from Newton’s experiments, but Sugimoto’s squares are studies of the colours and spaces in between these dominant hues. He commented in a recent interview that in Japan there are over two hundred names attributed to an equally plentiful array of identified colours. It is as though Sugimoto has taken Newton’s early Enlightenment experiments and re-illuminated them with an expanded register and philosophy of seeing.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Opticks series installation view, Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024. Image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley

Perhaps the biggest illusion is Sugimoto himself. We come to the end of the exhibition feeling as through we have traversed great tracts of art history and photographic practice all the while circumnavigating the globe. It is almost inconceivable that this is a solo show, conceived in the mind’s eye of a single artist and conjured largely in interiors, domestic quarters, and the confines of a darkroom.

Elisa deCourcy is a writer and curator based in Kamberri/Canberra. Between 2020-23 she was an Australian Research Council DECRA fellow in the Centre for Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University. Her monograph, Colonial Photography, is in press with Miegunyah/Melbourne University Press.