Raafat Ishak & Damiano Bertoli: Hebdomeros

Paris Lettau

The irony of Hebdomeros is that the exhibition teaches us more about the Italian 'metaphysical' painter Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) than it does about either of its two collaborating Melbourne based artists, Raafat Ishak and Damiano Bertoli.

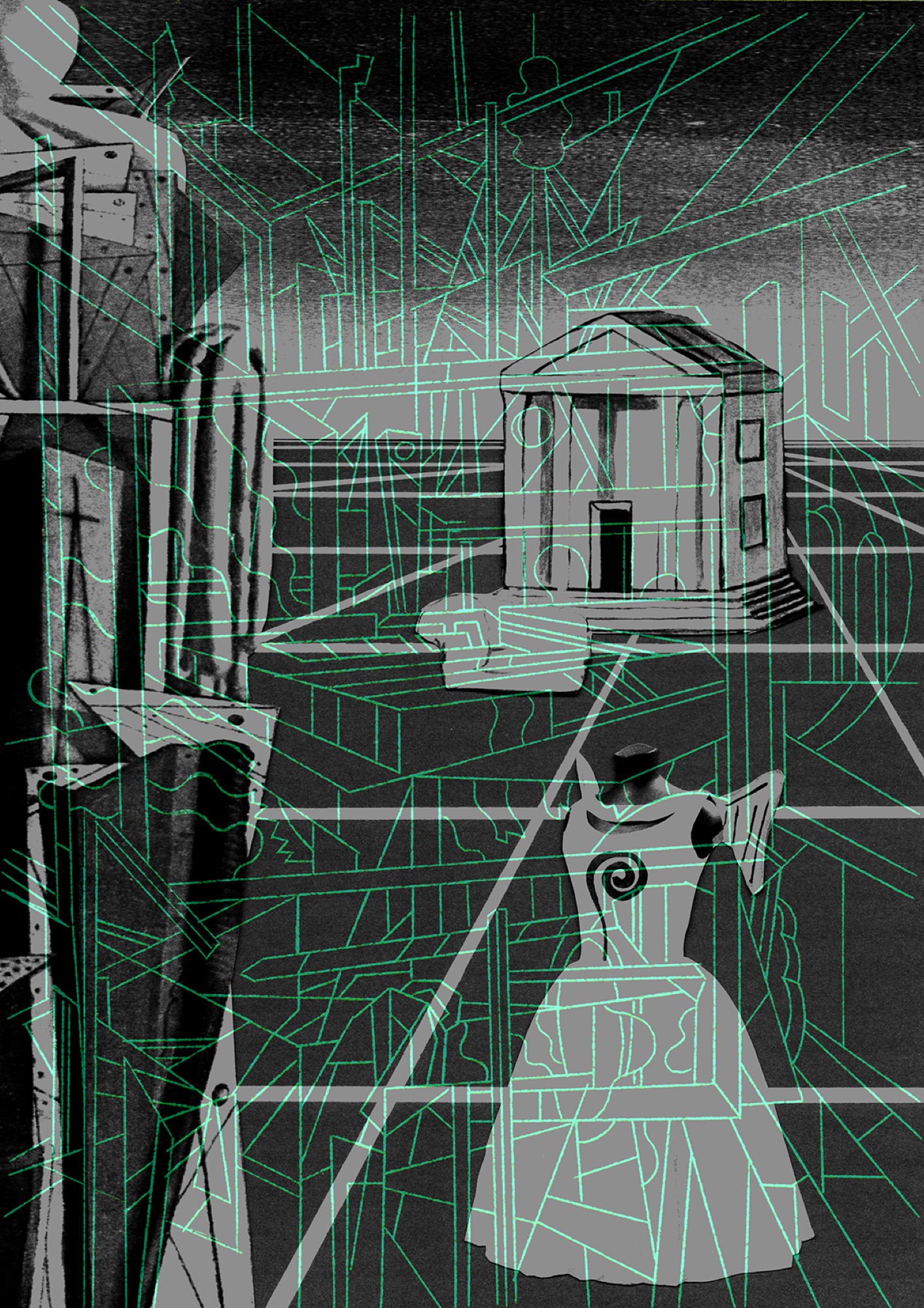

The modest exhibition, which accompanies Ishak's solo exhibition 1977 (in Sutton Gallery's adjacent room), takes its title from de Chirico's short 'surrealist' novel Hebdomeros (1929 )—whose plotless story famously opens at the steps of a 'strange building' that 'looked like a German consulate in Melbourne.' The exhibition comprises just nine small (42 x 30 cm) works that draw on the artists' mutual interest in de Chirico, which are presented as three sets of three (like three triptychs). Each 'triptych' in turn consists, from left to right, of one pencil drawing by Bertoli, one printed work by Ishak and one collaborative work produced by overlaying a work of each artist.

This is not the first time Bertoli and Ishak have collaborated. They previously produced an 'Italo-Egyptoid' (the artist's respective backgrounds) themed series drawing on Silvio Berlusconi's liaison with sex worker Ruby Rubacuori as well as North African 'clandestini' selling fake designer goods on Italian streets (the works also appropriating motifs and figures from de Chirico's work).

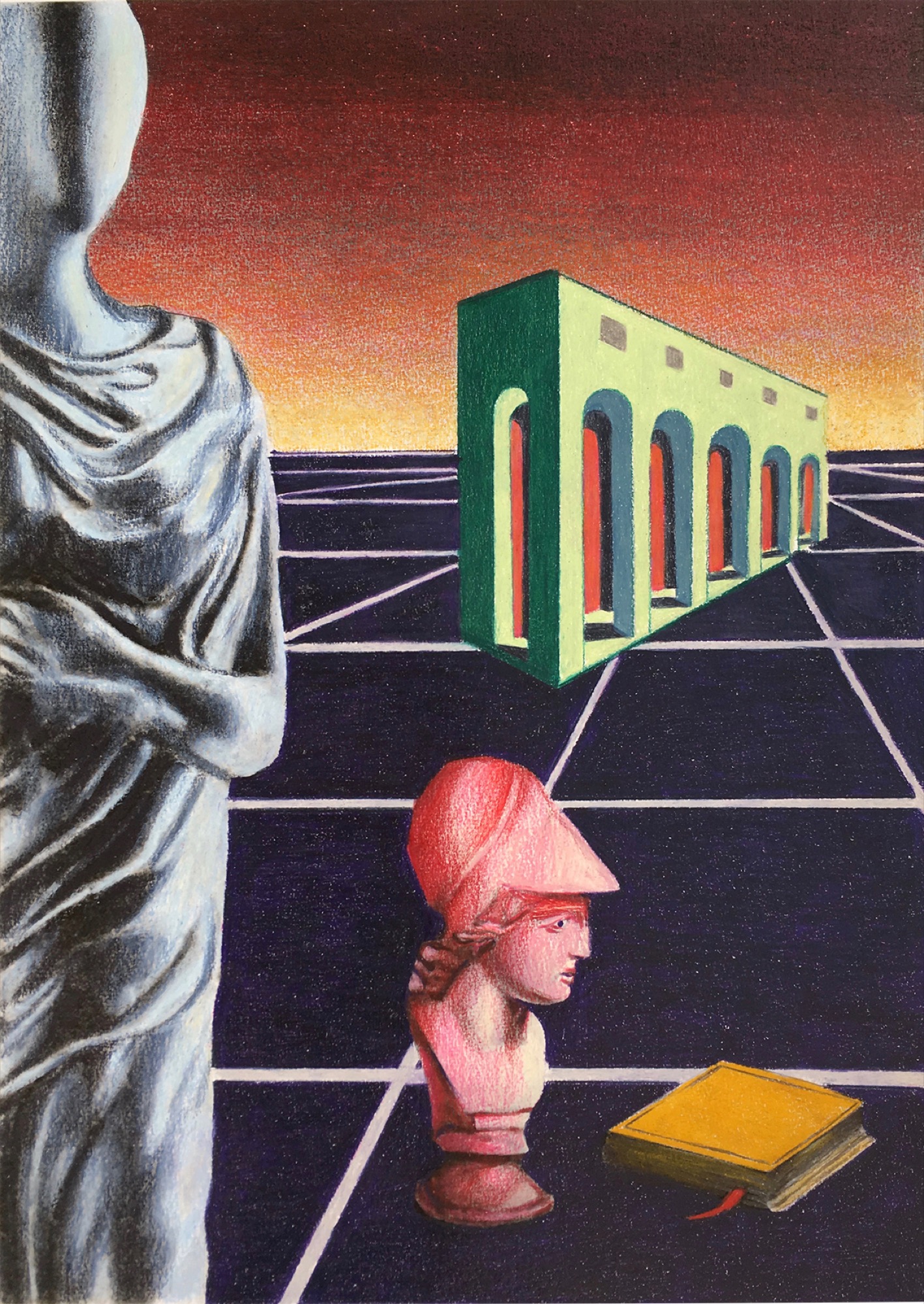

The metaphysical art of de Chirico traces mysterious affinities across time and space. It shows his own exploration of hidden cosmological realities, sedimented mythic anxieties that have accumulated in the Mediterranean's classical traditions. De Chirico's early (universally loved) metaphysical paintings show desolate melancholic urban cityscapes with displaced classical figures composed in ironic pictorial non sequiturs (think of the classical bust next to an enormous tacked-up orange glove in The Song of Love (1914)).

Yet, as the critic Wystan Curnow has pointed out, artists have long admired de Chirico for the very qualities that would, after the 1920s, come to damage his reputation. Not only were de Chirco's late works so often (and wrongly) dismissed as a kitsch neo-Classical 'return to order', but his 'late style' was also filled with stylistic 'faux pas', alleged plagiarism (of himself and others), controversial backdating of works and the absence of an identifiable oeuvre with a clear linear evolution.

It is these qualities that are both Bertoli's and Ishak's way into de Chirico. Bertoli's practice has long hinged on the modernist strategy of collage. This is seen in Bertoli's ongoing series 'Continuous Moment', including his (now idiomatic) appropriation of the utopic urban grid forms and collage strategies of Italian architectural practice Superstudio (founded in Florence in 1966—a kind of 1960s 'vaporwave' style), as well as appropriations of the Memphis Group (Milan in the 1980s), or an unperformed play written by Picasso in his series 'Le Désir … Rehearsal' (2013). The same strategy continues in the three drawings presented in Hebdomeros.

Bertoli's drawings are compelling both in themselves and as 'plagiarisms' of de Chirico (remembering, of course, that plagiarism is one of de Chirico's modi operandi). Only Bertoli re-ironises de Chirico by appropriating figures from both de Chirico's 'early' and 'late' works—in The Serenity of the Poet (2017) this includes a horse from Cavalli in Riva al Mare (1929) and that green ball from The Song of Love (1914). Yet Bertoli also shows that 'early' and 'late' are false categories when applied to the enigmatic power of the early 'metaphysical' works, which cannot be separated from the artist's lifelong obsession for mythologising and ironising his own artistic legacy. His practice forms, to use Bertoli's own term, a 'continuous moment.'

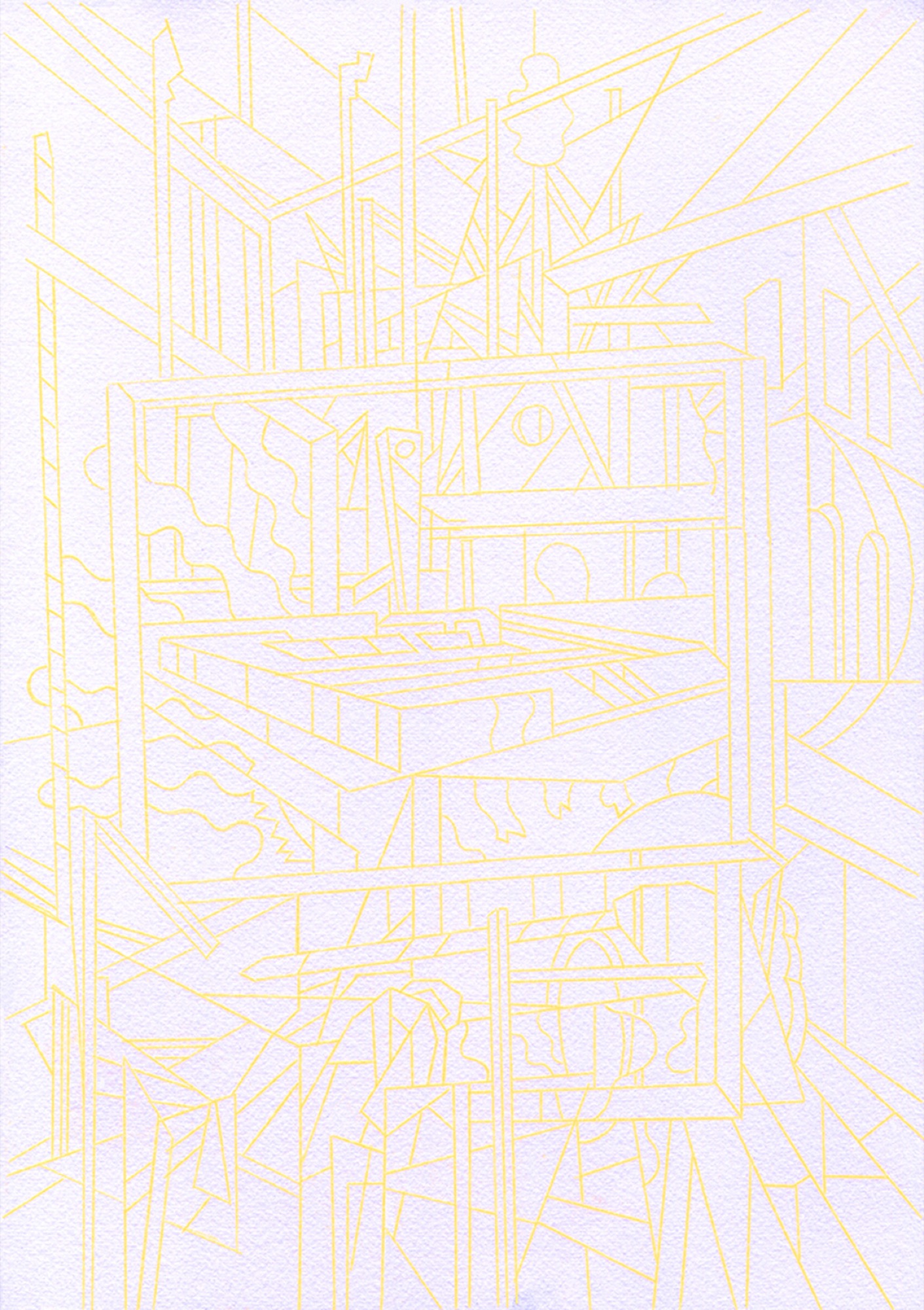

Ishak too draws on the legacies of modernism in art history and architecture. Unlike Bertoli's 'plagiarisms', though, Ishak constructs delicate, faint yellow abstracted architectural forms drawn from de Chirico's paintings, as seen in The sooth sayer and the silent statue (2017) (a seeming reference to The Soothsayer's Recompense (1913)). However, like Bertoli, Ishak's operative logic is also collage (as can as well be seen in the seven large works on MDF presented in the adjacent gallery in 1977).

The pervasiveness of temporal tropes (especially the evocations of mythic temporalities) in both artists’ works, however, makes the term 'montage' rather than collage seem more appropriate. And this is also true of the final collaborative works (which are editioned prints), in which Ishak's abstracted forms are digitally 'montaged' onto Bertoli's drawings.

But let us return to the original claim of this review: that Hebdomeros tells us more about de Chirico than it does about either Bertoli or Ishak—as if each is pulled into a metaphysical vortex where artistic agency is surrendered to de Chirico's mysterious powers.

How so? A clue can be found in de Chirico's presence throughout Australian art history. Think, for instance, of Imants Tillers' ongoing 'collaboration' with de Chirico, which he began in 1982, as seen in his well-known painting Antipodean manifesto (1986). And de Chirico’s centrality in Tillers’ influential argument in his seminal essay Locality Fails (1982), which ends with an anecdote drawn from the Hebdomeros story. Tillers also famously instigated a collaboration with Gordon Bennett by sending him a letter in which he proposes the two make a collaborative work 'regarding an image received telepathically' (Tillers claimed this) by Tillers from Bennett. A series of exchanges eventually resulted in the work Richochets, Manifest Destiny (A Painting for the Distant Future: 2001?), Window onto a Shadow Universe (1993). There too, printed in the upper right-hand corner of Bennett's letterhead is the spectral presence of de Chirico (Bennett, like Bertoli's Cartesian topographies, Ishak's abstracted architecture and de Chirico's desolate urban-scapes, deployed the de-temporalising perspectival grid to ironise his figures). Or consider again the 2014 exhibition Dreamings. Australian Aboriginal Art Meets De Chirico held at the Villa Borghese, where Tillers' painting mediated an encounter of Australian Aboriginal painting with de Chirico's 'metaphysical' art. Has de Chirico assumed a metaphysical agency over Australian art?

In the nine, small and in a certain sense rather unassuming works of Hebdomeros it is de Chirico who is the showman. De Chirico carries out the artistic labour for Bertoli and Ishak (as the metaphysical painter has also done for Tillers), as if a collaboration has been carried out without the conscious knowledge or volition of either party. But this is only because in Australian art 'de Chirico' has come to represent more than an historical artist who lived, worked and died in the 20th century. De Chirico also names both a method and a topos (a place of inexplicable contacts, like Tarkovsky's 'Zone' in his sci-fi film Stalker (1979)); a 'medium' of collaboration and a mythic constellation within Australian art. In Bertoli's and Ishak's Hebdomeros, we can see this constellation flash before us.

Title image: Damiano Bertoli, The Serenity of the Poet, 2017, pencil on paper, 42 x 29.7 cm. Image courtesy the artist.)