Heather Shimmen—The sun shining ultravioletly one day upon the protean sea

Sheridan Palmer

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, and James Gillray gave animals distinctive personalities and names that were capable of interventions or facilitating fateful or hilarious outcomes; Goya animated his etchings with owls, bats, and donkeys to great effect during the Spanish Inquisition. Empowering animals through myths, literature, poetry, nursery rhymes, and cartoons might seem a quaint way to transmogrify humanity’s morals and politics, but it is an effective way to pull out darker stories about historical events. In Heather Shimmen’s current exhibition at the Latrobe Regional Gallery, in the Gippsland township of Morwell, her large linocut prints and sculptural three-dimensional assemblages are populated with Australian indigenous creatures that entice us into fabulous realms, in which Shimmen weaves politics, environmentalism, racist tropes, and feminising tales, mostly of colonial-settler women adrift and alone in their new hostile territory. As Australia undergoes its own activist and rhetorical debates about sovereignty and the impact of European colonisation, more recently highlighted by the Voice referendum, the vandalism of public monuments of colonial figures, or the removal and relocation of Captain Cook’s Cottage from the Fitzroy Gardens, it may surprise some that Shimmen has been critiquing Australia’s cultural identity from a white female perspective in her art for well over two decades.

Using a repertoire of animals as protagonists to carry historical narratives may at first seem like a playful decoy, but in Shimmen’s installation wall work A Rogue Son and a Royal Visit, 2019–21, she tackles empire with a constellation of antipodean animals surrounding the imperial trunk of colonialism. The work was inspired by a satiric account of the first royal visitor to Australia in 1868 by Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh, who was “Welcomed to Australia by the Natives of this Country”. This was lampooned by a cartoonist with a chorus of native animals holding a long scroll of formalities. Shimmen transforms the scenario into a large work using embossed aluminium, hand stencilled inked lines over felt, and faux fur and other materials—as she explained, she likes to “get the print off the page”—and the message, while animistic, is markedly political. On his arrival in Adelaide, the Prince immediately went on a shooting party, and thus Shimmen reinstates indigenous animals, such as the kangaroo, cockatoos, crows, marsupials, bush rats, swans, echidnas, and emus, as the key actors within the larger narrative of this imperial and imperialising visit.

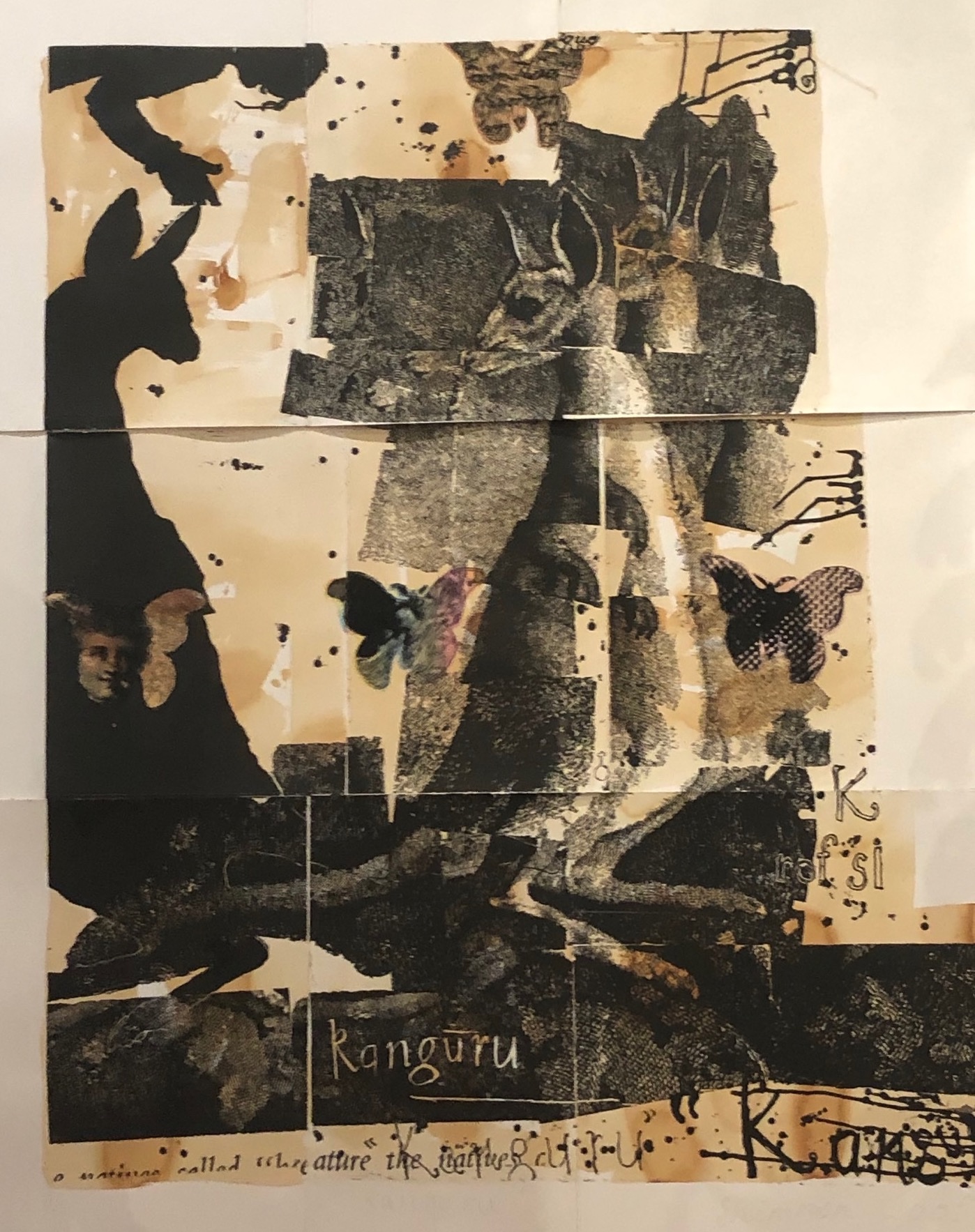

In 1772, George Stubbs the British artist famous for his animal paintings, was commissioned to paint the Kongouro from New Holland. With the sun setting over the darkening forests of the Blue Mountains, he positions the marsupial so that it becomes a “romantic” icon and a symbolic mascot for Britain’s discovery of Australia. The kangaroo was not just a quixotic antipodean animal, but Barron Field (a newly appointed colonial judge who declared Australia as terra nullius), who also wrote poetry, described the kangaroo as a “divine mistake.” Moreover, the animal was a recreational replacement for the European’s hounds and foxes. Shimmen takes the engraved version of Stubbs’ painting and transforms it into a large lino print titled Kanguru, where her image is that of a trapped animal or target, its terrified stare as if caught in a rifle’s barrel sight. Her multi-layered visual language articulates the colonial crime and the interloper’s cruelty, and the animal’s black antipodal silhouette returns the haunting image squarely back onto the white-fella’s trail of extermination.

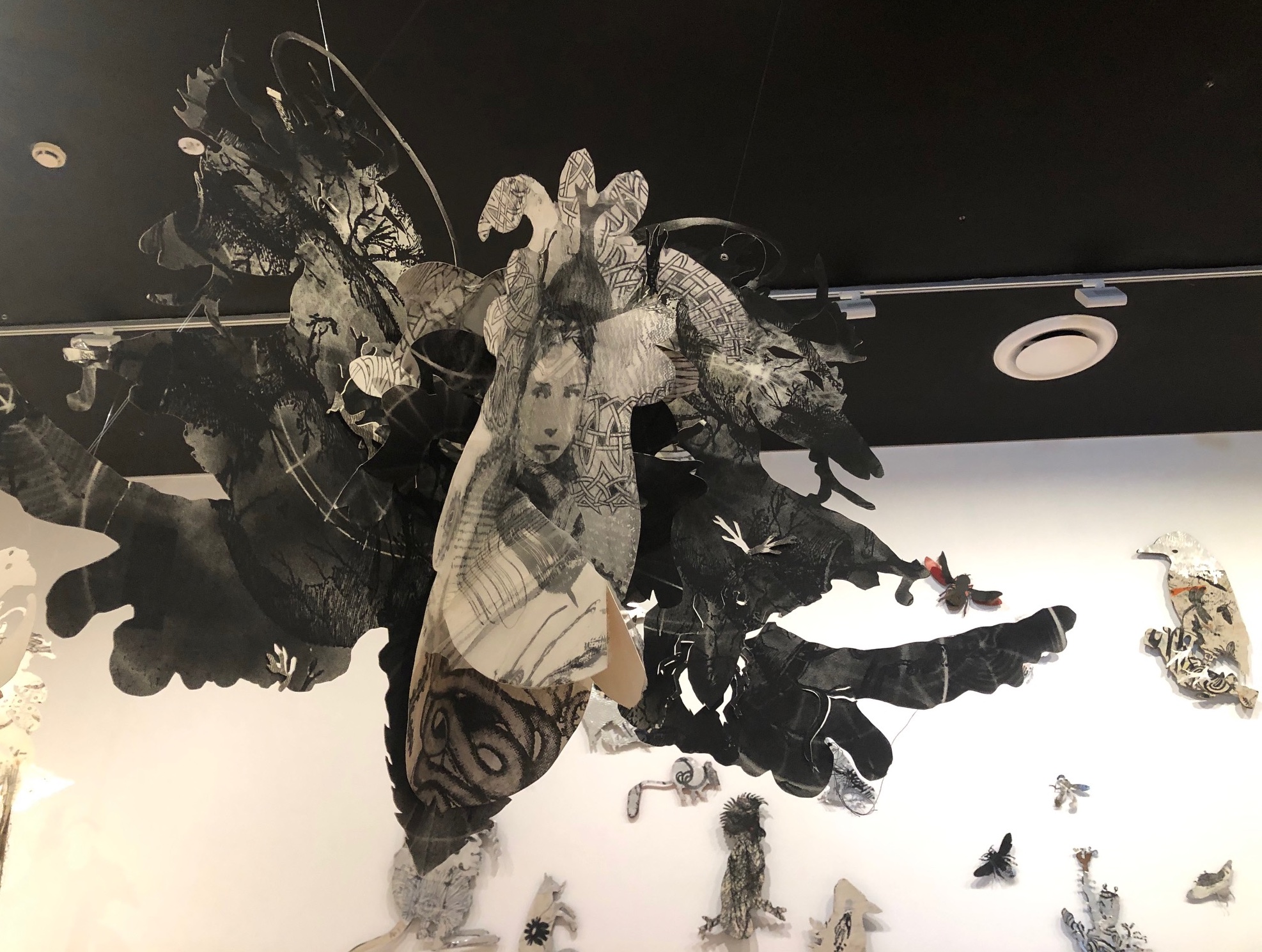

A prolific printmaker, Shimmen literally cuts deep into her medium as well as into the psyche of the bush. Drawing against the European model, she creates microcosms of flora and fauna, with insects, rodents, quadrupeds, birds, and reptiles populating her large menageries. She attributes her alchemic use of materials to the experimentation that her teachers Len Crawford, George Baldessin, and Andrew Sibley encouraged during her student years at RMIT in the late 1980s. She has since pushed the boundaries of printmaking, embellishing and politicising her imagery. Her constructed three-dimensional cut-outs are patterned, embossed, and perforated, with tangled threads, feathers, and shimmering organza that adds a sense of feminising exotica to her installations.

Shimmen’s large hand-coloured and stencilled panels draw upon personalised experiences and her semi-reclusive coastal life in Bunurong country in South Gippsland where she is surrounded by native creatures and flourishing bushland. Entomology, anthropology, ethnography, as well as colourful Oceanic animism pervades her imagination—as a child Shimmen moved between two very different cultures, Melbourne’s Anglocentric urbanised society and the remote jungle plateaus of the New Guinea highlands, where her white Australian parents co-leased a farm. Initiated into the tropical, not as tourist but as a local teenager, she absorbed the native life and played with carved wooden figurines, shells, and brilliantly coloured beetles and butterflies. Adorned with wildly scented flowers, she travelled in the back of utes with a throng of highland children singing to ward off evil spirits. Understandably, Shimmen’s sense of the “exotic” runs deep, and she uses it both as a mystifying veil to avert banality as well as to transport us elsewhere.

Intrigued by bush tales of First Nations people (her mother belonged to the Aboriginal Advancement League), and the vernacular language of early Australian settlers and farmers, Shimmen is conscious of “the many thousands of stories that die every day” or that are forgotten and erased. She regards research as an important component within her art making, and foraging though stories of explorers, diaries, and Australian history she collects and embeds ideas within her prints. Her highly individualised iconography is commanding, tantalising, and at times discomforting, especially when narratives reveal tragic circumstances, lies, and manipulation that run like fault lines across cultural zones and centuries. In The Wisdom of Grasshoppers, 2019, Shimmen returns to the subject of body decoration, linking tribal scarification with the cosmetic excess of European women in theeighteenth and nineteenth centuries; many of the latter painted large beauty spots to conceal smallpox scars. The reference to grasshoppers suggests plagues, while the woman’s face is based on the aristocratic Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, herself a survivor of smallpox, who had witnessed Turkish women in Constantinople during the Ottoman empire using inoculation methods against the deadly disease. Lady Mary petitioned for this to be introduced to Britain on her return but was harshly criticised and patronised by the medical elite and then largely forgotten.

Shimmen’s Suspended Anima, 2011, is a series of works that were realised as oversized artist’s books and combine pop-up elements, perforations, tangled threads, and concertinaed women’s faces within folds, again suggestive of the social, psychological, and physical strictures imposed on women throughout history. The kinetic mobility of these works cast subtle shadows across walls and animate the exhibition with an air of aesthetic diversity. With four large wall installations that use well over two hundred individual pieces, this enormous display of work is as sensational as it is semi-retrospective.

Dr Sheridan Palmer is an art historian, curator, and Honorary Fellow at the University of Melbourne. She has worked at the National Gallery of Australia, as a curator at the Ballarat Art Gallery, published extensively and awarded numerous grants and fellowships for her biography of the eminent art historian Bernard Smith.