Installation view of Hans Arp works, generously gifted by the artist’s estate Stiftung Arp e.V., on display at NGV International. Photo: Garry Sommerfeld.

Hans Arp and Lee Bul

Anna Parlane

If you’re looking to step out of the media firehose surrounding a certain election result, there’s pleasure to be had in the NGV’s quieter, unadvertised collection exhibitions. Go past the construction hoardings that have been set up around the forthcoming Yayoi Kusama extravaganza, and it’s possible to see an exhibition of new acquisitions by modernist French-German sculptor Hans Arp, which sits in interesting relation to an installation by contemporary South Korean artist Lee Bul, another collection work currently on display. Of course, aesthetic pleasure is never really an escape from politics. A core interest in both artists’ practices is the question of how to convey the mutability of a living body using sculptural form, and the poignancy of these works and their pairing lies in their capacity to crystallise and represent issues raised during the recent election cycle. Arp and Lee’s exploration of sculptural questions about surface and depth, unity and fragmentation, purity and abjection speak to the renewed political struggle over bodily autonomy and reproductive rights, but also—more abstractly—to how the presidential candidates handled or glossed over the diversity of the electorate in their efforts to remodel the political establishment.

The impetus for the Hans Arp exhibition is the NGV’s recent substantial acquisition of twenty-four works by the artist. In displaying these works, the museum’s curators have sought to use Arp’s work and his modernist sensibilities to probe and reframe other pieces from the collection. Arp’s Flower Muzzle (1960) is paired with the flower-power colours of Lee Krasner’s triumphant post-Pollock Combat (1965), and his Torso (1953) overlooks Francis Bacon’s voyeuristic Study from the Human Body (1949). A sightline through into the Surrealist collection show in the next room centres Salvador Dali’s Mae West Lips Sofa (1937-38). The exhibition tells a light-hearted story about voluptuous curves, a fetishistic appreciation of materials, sensuality, and pleasure. It is, in essence, an exploration of modernism’s sex appeal.

Installation view of Lee Krasner, Combat, 1965, oil on canvas, and Hans Arp, Flower Muzzle, 1960, plaster version cast 1980s, bronze version cast 2021 (ed. 5/5), on display at NGV International. Works by Hans Arp generously gifted by the artist’s estate Stiftung Arp e.V. Photo: Garry Sommerfeld.

This acquisition of Arp’s sculptures is part of a major series of gifts from the Stiftung Arp e.V in Germany, one of three foundations established to oversee Arp’s estate after his death. Nine institutions received works as part of this gift, with the NGV the only southern hemisphere beneficiary. The Nasser Sculpture Center in Texas, which also received twenty-four works, explained that “with authorized posthumous casting of Arp’s sculptures almost complete, Stiftung Arp is dispensing its collection of plasters and its archive to institutions across the globe, establishing a new model of international, cooperative research.” Stiftung Arp’s pivot towards research, philanthropy and transparency over recent years is perhaps an effort to turn the page on an earlier unfortunate period in the foundation’s history. Arie Hartog’s authoritative 2012 book on the subject recounts how, after Arp’s death in 1966, there was a frenzy of production in his studio, which led to a frenzy of legal action between the various parties involved in his estate. While Arp worked primarily with plaster in his studio, he typically reproduced finished works in bronze or stone at the point when they were sold to a collector. However, Hartog writes that, within twenty years of the artist’s death, “plaster models had turned into potential capital,” noting that “the sculptural oeuvre of Hans Arp has more than doubled since his death.” The donation of plaster casts to museums seems to be the foundation’s way of keeping them off the market by designating them as “working models” for research purposes. However, as Hartog points out, the plaster casts held in museum collections invariably take on the aura of works of completed art, as well as reinforcing the erroneous impression that a milky white finish is characteristic of Arp’s sculptures.

Installation view of Hans Arp, Torso with Buds, 1961, cast 1970s, plaster, generously gifted by the artist’s estate Stiftung Arp e.V., on display at NGV International. Photo: Garry Sommerfeld.

The question of Arp’s working processes and materials is addressed in the NGV’s show, but it is definitely secondary to the narrative about formal sensuality that is bolstered by the aesthetic appeal of the plaster works themselves. The NGV also cites, as is standard, Arp’s avant-garde credentials. He was a founding member of Zürich Dada and moved in Surrealist circles as both a poet and visual artist. The exhibition includes a series of prints by Max Ernst to which Arp wrote a stream-of-consciousness introductory text in the 1920s. However, unlike many of his Dada and Surrealist colleagues, Arp was always more into harmonious ambiguity than political radicality or anti-establishment action, and his work is framed here as this more anodyne form of abstract modernism. He pioneered “biomorphic abstraction,” and his works draw on human and vegetal forms to produce something smooth, curvaceous, and bodily yet ambiguous. Torso with Buds (1961) is an obvious example of how the immaculately sanded white plaster surface of the work serves to facilitate this marriage of forms by erasing any joins or disjunctions.

While the NGV’s wall labels repeatedly mention Arp’s interest in chance processes, it seems to me that he exercised a very high degree of control over the production of his works. They are Surrealist only to the extent that they are ambiguous, encouraging viewers to perceive multiple anthropomorphic and natural resemblances that slip smoothly in and out of visibility as you circulate around the form. Arp used plaster in the studio as a way of refusing stasis and reworking his forms: he would chop up and reconfigure sculptures, before sanding the plaster smooth again. However, in the gallery, the smooth white plaster finish has the opposite effect. It amplifies the conservatism of the works by endowing them with an aesthetic of purity, which in turn makes their evocation of natural processes of growth, transformation, and reproduction feel rather bloodless. There is a significant contrast, for example, between Arp’s extremely hetero celebration of a slim, girlish figure seemingly blossoming into youthful fertility in Torso with Buds and Bacon’s very queer (and, it has to be said, also pretty creepy) voyeurism in Study from the Human Body, a work which is soaked in the power dynamics of shame and desire.

Installation view of Francis Bacon, Study from the Human Body, 1949, oil on canvas, and Hans Arp Torso, 1953, cast 1960-82, plaster, and Tree of Bowls, 1947, cast c. 1970, plaster and shellac, on display at NGV International. Works by Hans Arp generously gifted by the artist’s estate Stiftung Arp e.V. Photo: Garry Sommerfeld.

This framing of Arp as arch modernist is not, of course, new. This version of Arp’s work proved influential on mid-century sculptors like Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, as well as contributing to the mainstream popularisation of modernist abstraction. Key to this influence was the perception, conveyed in Carola Giedion-Welcker’s 1957 monograph, that his abstract works tapped some essential harmonious relationship underlying the visible world. In Giedion-Welcker’s words, his “universal and elementary forms” served to fuse “natural and human substance into a new sculptural unity.” There’s a sense, then, not only that the formal ambiguity of Arp’s sculptures is facilitated by the smooth surface that allows their various natural referents to blend seamlessly into each other, but that this also rests on a pretty conservative foundation. The posthumous redefinition of his works as neoclassical white simply draws out this underlying fact.

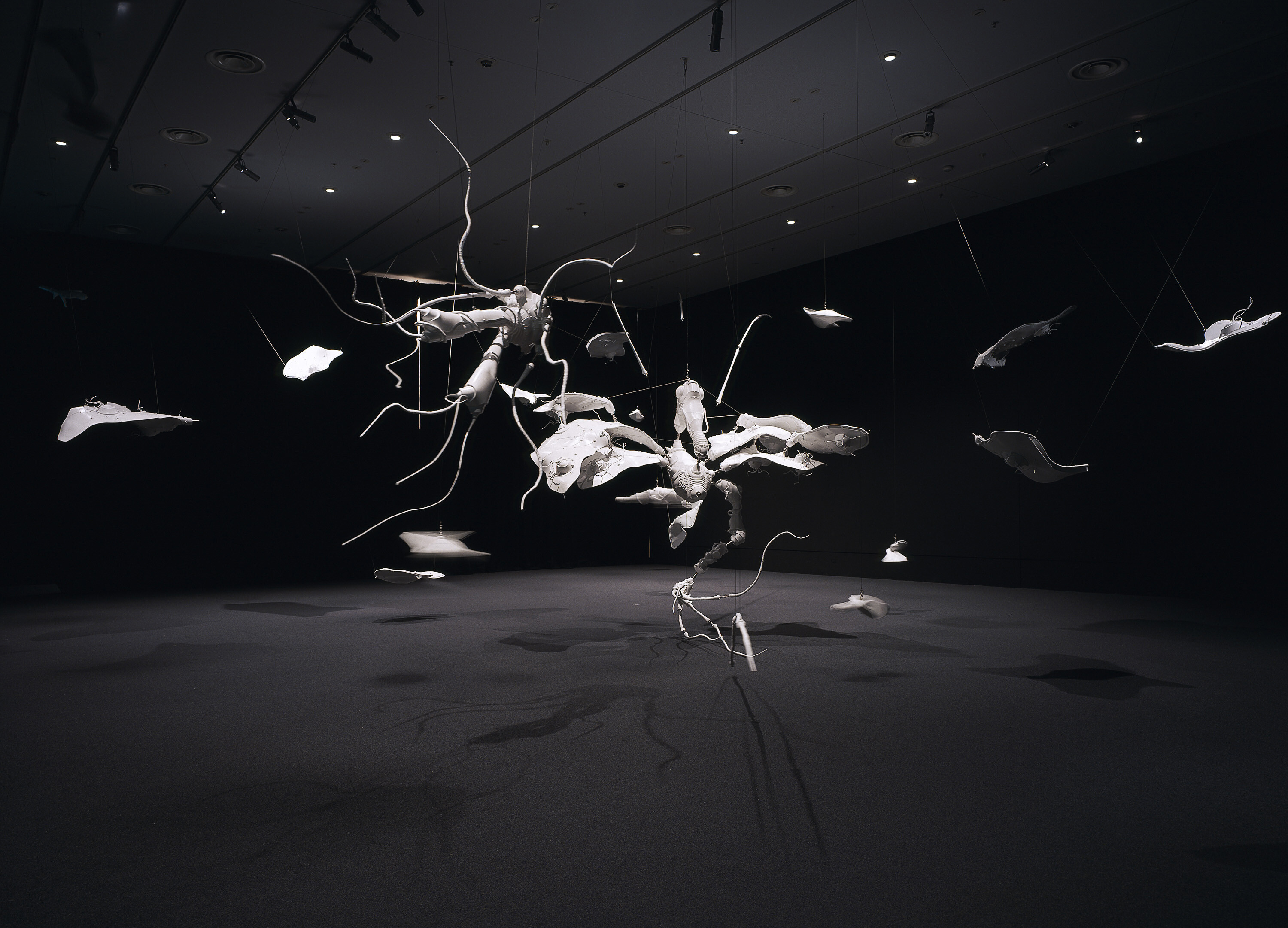

Lee Bul, Untitled, 2003, polyurethane, enamel paint, stainless steel, aluminium wire, 495 × 1700 × 1200cm (installation), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, purchased 2004. © Lee Bul, courtesy Bartleby Bickle & Meursault.

The implications of this (re)framing of Arp’s work are, perhaps unintentionally, thrown into relief by the pairing of Arp’s work with that of Lee Bul. Lee’s rapid rise to prominence took place during the 1990s globalisation of the western art world, when claims to universality were supplanted by a celebration of diverse perspectives and cultural difference. Her sculptural works, like Arp’s, explore the associations linking human bodies and other natural forms, but for Lee the bud or growth is typically not seen as sexy so much as horrific. Her ambiguous sculpted bodies—for example, the giant flesh suit she wore for a series of wonderfully nutty performances in 1989-90—are tumorous, tentacular and grotesque. Far from an opportunity to immortalise a smooth curve in immaculate white plaster, for Lee bodily fertility and pregnancy are understood as a horror show of pain and endurance, as in the incredibly raw two-hour 1989 performance where she recounted her own experience of abortion.

The narrative told about Lee’s practice, like Arp’s, consistently invokes her early association with aesthetic and political radicality. In Lee’s case, writers invariably mention how her mother’s political activism impacted the artist’s upbringing during Park Chung-hee’s military dictatorship, and how Lee’s purposefully confrontational early performance works responded to the feminist consciousness-raising and democratisation movements of the 1970s and 80s. In Lee’s early works, emphasising the body’s messy, taboo aspects was a way of countering the idealisation of female bodies (which is to say: countering the misogynist disgust directed at the actuality of female bodies). Processes of aesthetic beautification are for her associated more with gendered labour than with some frictionless ascent onto a higher plane of essential forms.

Lee Bul, Untitled, 2003, polyurethane, enamel paint, stainless steel, aluminium wire, 495 × 1700 × 1200cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, purchased 2004. Photo: Anna Parlane.

Lee’s Untitled (2003), the work currently on show at the NGV, is from her Anagram series of the early 2000s. This was the moment in Lee’s practice when her edgy, ephemeral earlier works gave way to static sculptural forms more suitable for long-run biennale exhibitions and museum acquisition. The body-horror themes characteristic of her earlier practice are still there, but in a format that is strangely remote and sanitised. Riffing off Donna Haraway’s 1985 “Cyborg Manifesto,” which Lee has acknowledged as a key influence, the work is a fragmented and exploded cyborg body which combines aesthetic elements from aircraft, insect anatomy, robotics, and prosthetic limbs. Each part has been cast in polyurethane and uniformly sprayed with white enamel paint.

Lee’s Anagram series clearly also taps the pregnancy-horror themes of the Alien film franchise, which through the 1980s and 90s so effectively deployed H.R. Giger’s biomechanical aesthetic language. What the Anagram series lacks, though, is the Sigourney-Weaver-with-a-flamethrower energy that Lee embodied so successfully in her earlier performance-based works. Unlike the 3D realisation of Giger’s drawings for the Alien film set—glistening, quivering, intensely visceral—Untitled feels like it arrived in the museum straight from a factory production line, encased in moulded polystyrene packaging. You can almost smell the new plastic scent of the unboxing. Avoiding the fetishistic slippery smoothness of Arp’s artisanal hand-sanded plaster and highly polished bronze, the uniformly textured surface of Lee’s work is bland in its mechanical consistency. It’s like a model aircraft that has been mass produced as a series of neutral-toned plastic components, ready to be snapped together and painted.

Lee Bul, Untitled, 2003, polyurethane, enamel paint, stainless steel, aluminium wire, 495 × 1700 × 1200cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, purchased 2004. Photo: Anna Parlane.

Lee has talked about how the white finish of the works in her Anagram and earlier Cyborg series references Western neoclassical sculpture, and particularly the association with bodily perfection that it still somehow has (despite the fact that ancient Greek and Roman sculpture was originally gaudy polychrome, not white at all, and despite the indelible association with European fascism that neoclassicism acquired in the 1930s). The huge global popularity of the inhumanly flawless so-called “glass skin” that is a major recent achievement of the Korean beauty industry also comes to mind. The consistent pallor of Lee’s surfaces with their inert, mechanical finish knowingly taps into deeply entrenched and deeply conservative cultural assumptions about perfect bodies. Beyond the obvious racism of the ongoing association between whiteness and purity, however, both Arp and Lee’s works put the smooth continuity of their surfaces to work. In both instances, it’s used to amalgamate different bodies into a single ambiguous form. I do think that Arp was seduced by the perfection of his own materials: the aesthetics of purity that has been foregrounded by the posthumous emphasis on his white plaster forms was clearly already part of his practice to at least some degree. By contrast, Lee is alive to the horror as well as the appeal of a lustrous surface, its capacity to gloss over the real rage and vulnerability of a living body.

The recent US election campaign has picked up and reworked several twentieth-century political tropes, including the relationship between surface and underlying form. Harris presented herself as a champion of diversity and also a bulwark of establishment respectability. Trump’s major innovation was to theatrically drop the veneer of decorum, seemingly enabling access to the real substance under the surface and unleashing a dystopic tide in the process. Far from breaking the surface, however, Trump himself, and specifically the Teflon-coated audacity he acquired as a 1980s businessman, is currently acting as the impervious skin unifying an unruly body politic. How he’ll hold it together remains to be seen.

Anna Parlane is a lecturer in art history and theory at Monash University.