Spencer Lai: Contaminant, Figures

Amelia Winata

Spencer Lai's work is part of a contemporary exploration of the grotesque that taps into the destabilising qualities of late capitalism and considers its effect upon issues of identity, including gender and sexuality. This current was picked up on by Jonathan Griffin in his 2012 essay Rudely transgressing the boundaries between the elevated and the profane, published in Tate Etc. In it, Griffin notes that while the grotesque has its origins in the fifteenth century where it placed emphasis upon bodily deformation—as well as blood, guts, and all manner of other bodily fluids—its expression in contemporary practice is logical insofar as it considers all things generally swept beneath the surface in society's desire to present a squeaky-clean façade. He writes, 'It allows us to get (at least a partial) handle on some of the most unspeakably vile and frightening categories of human experience, and it does so with humour and a sense of the absurd.' The grotesque, indeed, constitutes equal parts repulsion and attraction. As such, it is a befitting blanket term for most things that constitute a world where a television show host is the president of the United States.

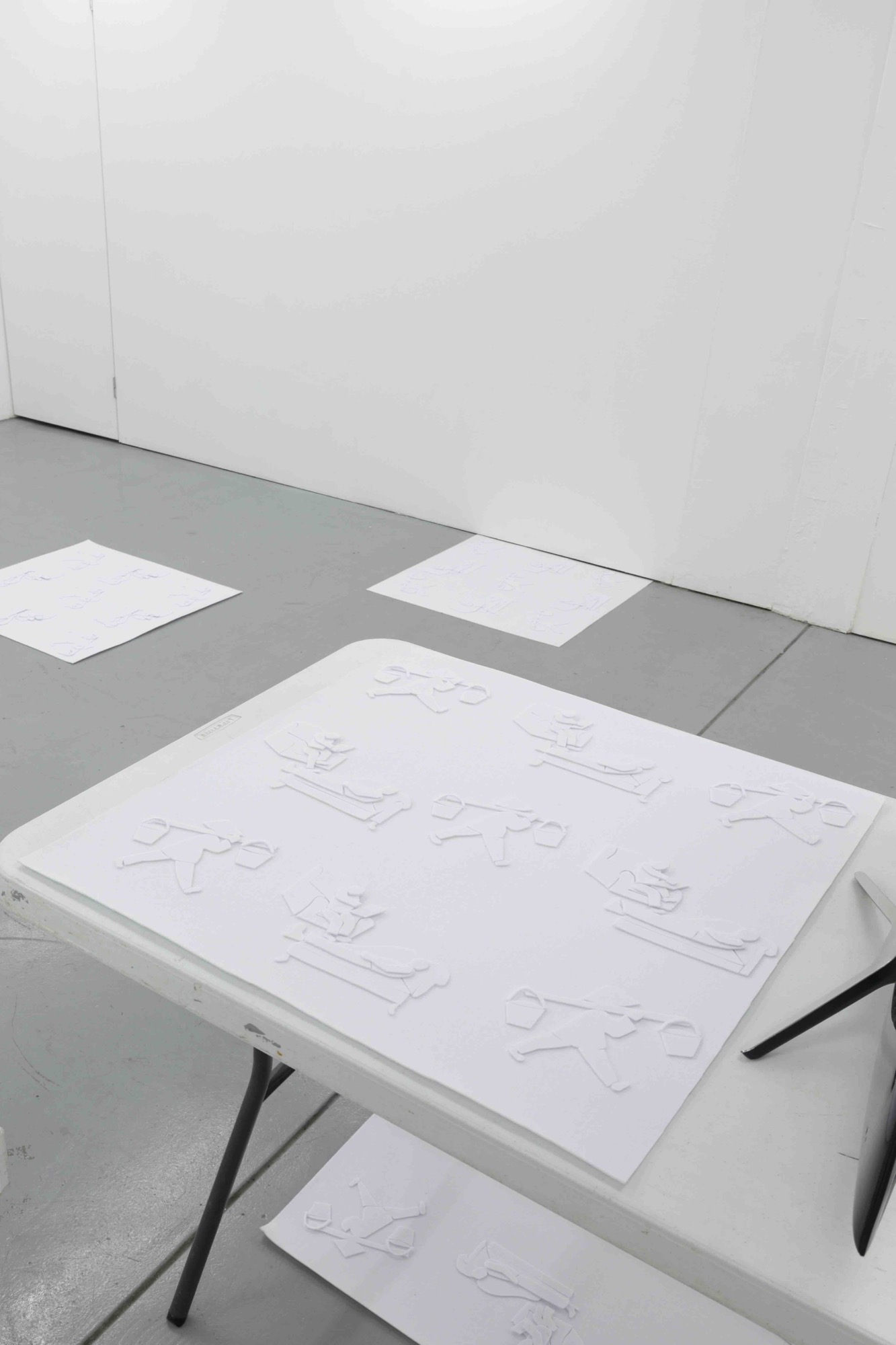

Lai's new exhibition at Fort Delta demonstrates an extraordinary progression in the work of an artist who is not long out of art school. Five monochromatic felt reliefs are dotted around the exhibition space: most are a direct tracing of an artistic representation of violence, historical and contemporary. Paired with a readymade collaboration with Lai's regular collaborator Jessie Kiely and an absurd video with a catchy soundtrack that follows you even after leaving the gallery, Lai's exhibition encompasses the attractive and the grating, the pretty and ugly, and the old and new to examine the flop in humankind's 'progression'. The grotesque weaves its way into this work in unexpected ways, subtly and slyly registering with its viewer through the slick finishes of the felt reliefs that are displayed. For the first time, Lai has used the figuration as a central aesthetic feature in their work, shifting away from the readymade to an emphasis upon technical skill, but rendering the illusion of classical painting flat and lifeless.

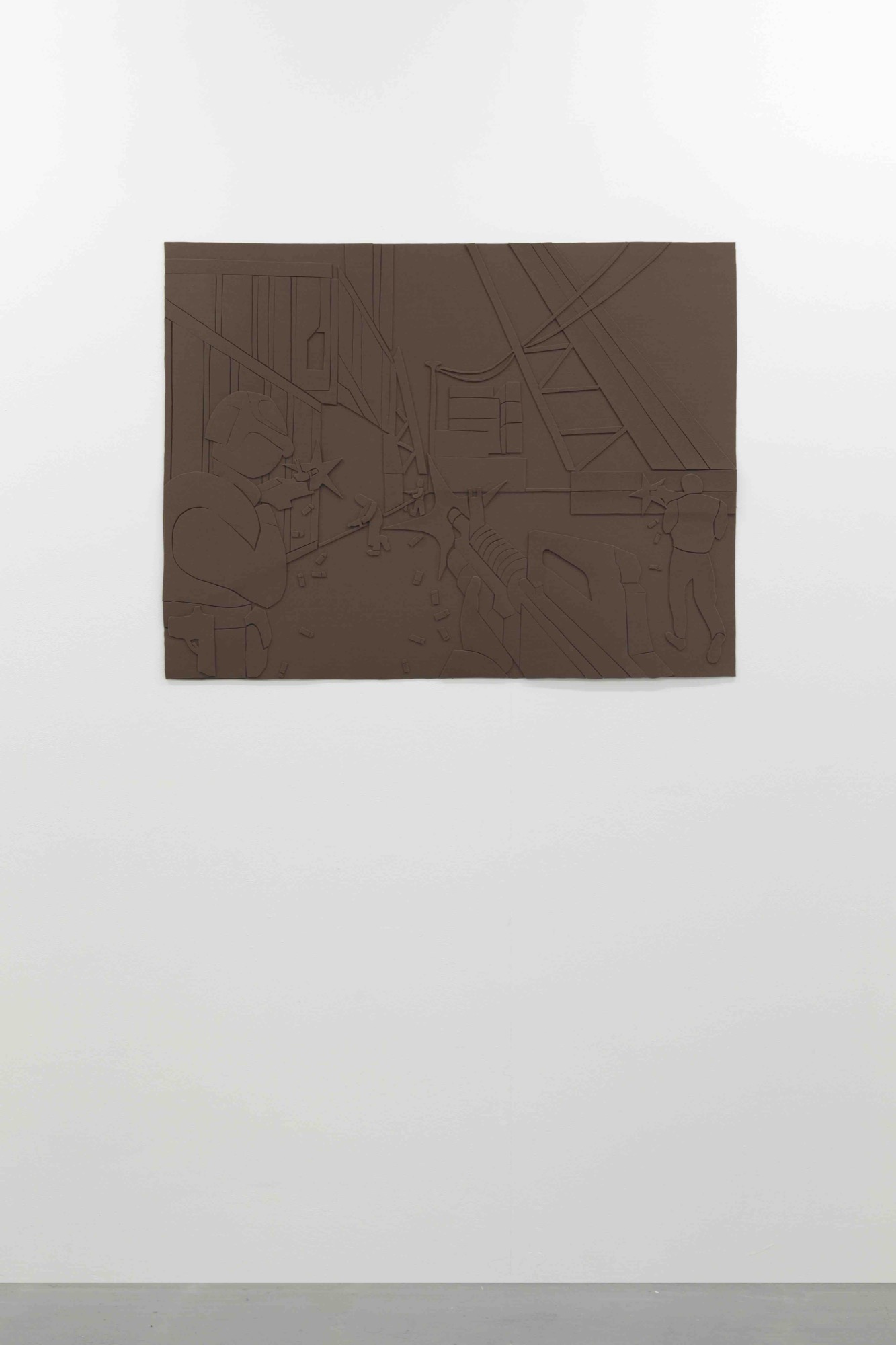

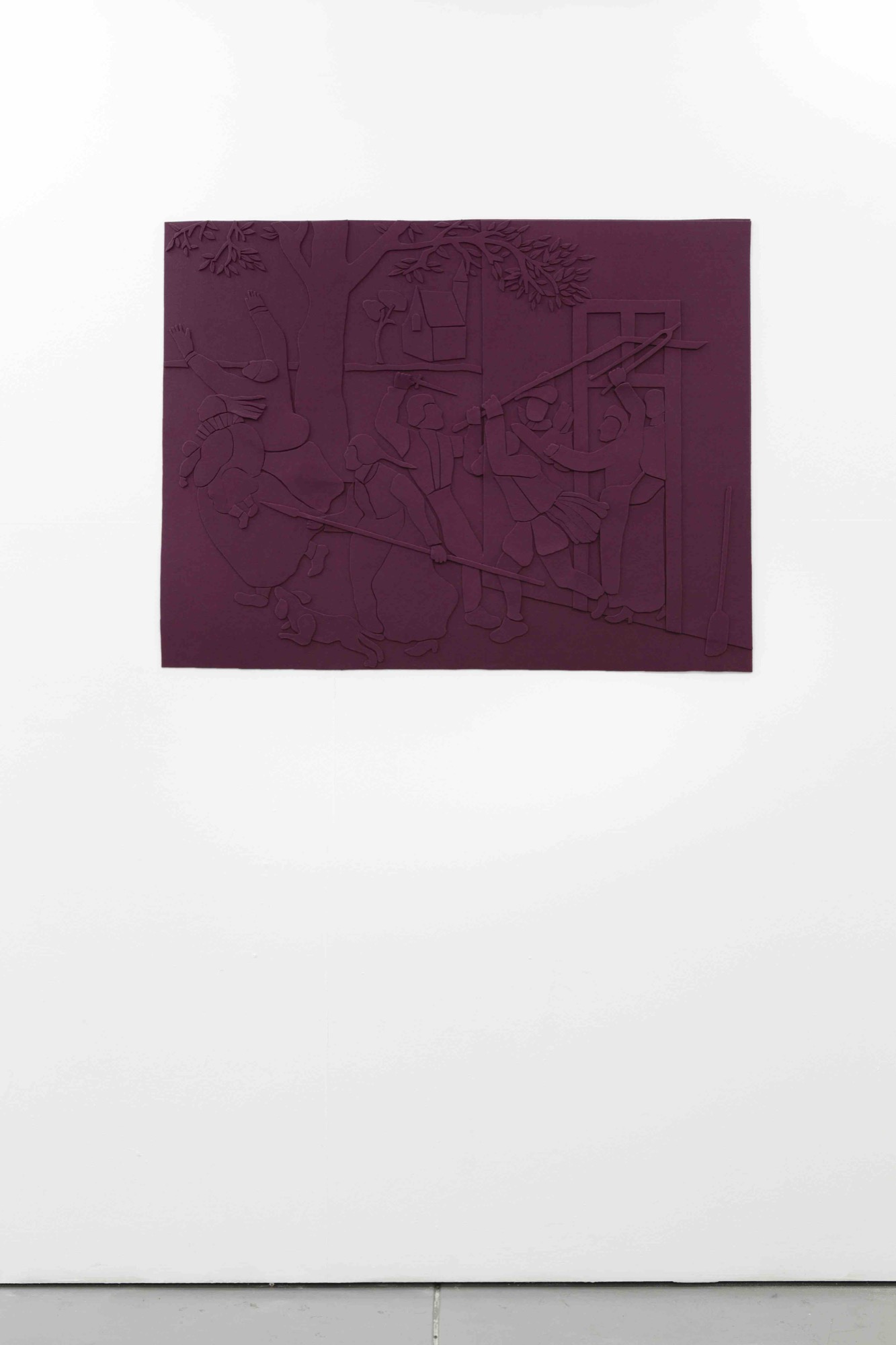

For their felt reliefs, Lai traces forward the 'advent' of the grotesque from its coinage in the fifteenth century, through to a seventeenth-centurypainting attributed to David Vinckboon before tracking further to the present day with references to more contemporary imagery. Lai has directly copied Vinckboon's An innkeeper and his wife driving out a family, circa. 1650,in purple, opaque felt to produce a monochromatic relief, Mauve (banished family), 2017, that is sumptuous and inviting in its precise execution. Vinckboon's and his workshop commonly produced paintings of either violent class clashes or upper class debauchery, and it is with this knowledge that the viewer realises the history of simultaneous violence and decadence that Lai interrogates. In contrast, the beauty of the work points to a desensitisation to violence that Lai follows up with reliefs of more contemporary images, including: an untitled work made in the Prinzhorn psychiatric institute around the turn of the twentieth century by a patient of Gustav Sievers (Red, (figures dancing), 2017); an undated example of deviant art depicting a torture rack and equipment, a tortured subject and their two torturers, perhaps from the early 2000s (Mustard (torture device), 2017); and a screengrab of the video game Call of Duty Black Ops III (Brown (first person shooter), 2017). Amongst all this violence, the gravity of the acts have been rendered null by the technique of felt appliqué and it is this marriage of an awful subject matter executed with a beautiful technique and inviting palettes that makes these works so absurd and absolutely grotesque. This body of work is more sober than previously seen by the artist, but it is also the most successful in Lai's oeuvre to date: here the artist trusts a more restrained aesthetic to convey the works' intent, and this demonstrates a huge leap away from their usual exploration of consumer objects and refuse.

This is not to say that Lai does not succeed in their use of kitsch when they do revisit it. Indeed, tongue-in-cheek elements continue to make an appearance in Contaminant, Figures. The video piece Betty (cartoon, drain, icon, song), 2017 is a bizarre but, ultimately, comical exploration of consumer culture. In the past Lai has co-opted mass-produced products and, in particular, fashion as a means of establishing a non-gendered space within a system that is dictated by binaries. Here, Betty Boop represents a visibility/invisibility binary that is also dictated by the hegemony of consumer culture: she is at once everywhere (keychains, clocks, fashion) but is simultaneously an agentless, extremely sexualised female figure that has significantly depreciated in cultural value since her 1930 debut. While people continue to collect Betty memorabilia, one can't help but feel it is with a sense of irony, as though the character is an image of excessive but vapid consumption.

Hand-held shots of Betty Boop paraphernalia are cut together to the soundtrack of Tove Lo's Habits (Stay High) (Hippie Sabotage remix) as though they were a music video, with each shot cut in sync with the music. The found videos of Betty Boop clocks and keyrings are funny insofar as these products even exist, but they are also unattractive: their production qualities are low and they do the opposite of making you want to consume them. Despite this, the upbeat dance track that binds the video together has the effect of forcing the viewer to continue watching or, at the very least, to continue listening. The song is cheap and catchy and acts as a mnemonic device for ingraining the images of the Betty Boop products in the mind of the viewer.

It was Andrea Fraser who said that the grotesque is 'the symbolic equivalent of collapsing and confronting the incompatible and composing them as representations, not so they appear as a contradiction, but so that they are confronted … producing an effect of humour.' Certainly, Trough, 2017 (created in collaboration with Jessie Kiely), embodies this sentiment. The work is comprised of an animal feeder presented in the centre of the exhibition space. This work epitomises the grotesque as defined by Fraser insofar as it is the definition of two incompatible things existing in a curious harmony. The trough suggests the organic and sets the viewer up to believe that animal feed or water will be offered by it. Instead, it houses a scant amount of petrol, the fumes of which have infiltrated their way into every corner of the gallery, their synthetic odour positioning the exhibition squarely within the twenty-first century despite the many references to centuries gone.

While it is apparent that Lai agrees with Fraser's thesis by combining clashing objects and images to create their work, it is also evident that they are testing the limits of what can and can not work in Western culture. Is it possible, for instance, for late capitalism to support and nurture conflicting ideals as opposed to simply co-opting them into normative standards? If Lai's felt reliefs say anything, it is that centuries of human 'progress' have continued to generate violence—only now that violence is flattened and repackaged as aesthetically attractive. In contrast, Lai's readymades and video push past the moment of complacency, asking the viewer to suspend their desire for aesthetic beauty and see the dirty underbelly that is the flip side of most all of our creature comforts. Certainly, it is necessary to be attracted to things, but an acceptance of their repulsion is what makes up Lai's contemporary grotesque.

Amelia is a Melbourne-based arts writer with an Honours degree in Art History. She is also the Sub-editor of un Magazine, a Research Assistant and an Arts Administrator.

Title image: Spencer Lai, Mustard (torture device), 2017, synthetic felt, 940 x 720 mm. Image courtesy of the artist and Fort Delta.)