Installation view of Grace Crowley & Ralph Balson on view at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, 2024, photographed by Tom Ross.

Grace Crowley & Ralph Balson

Jarrod Zlatic

At the centre of the current Grace Crowley & Ralph Balson retrospective at the National Gallery of Victoria is a pair of almost too-perfect paintings: standing upright, like sculptures, atop space-age silver plinths: an abstract painting by Crowley hangs on one side and on the other, an abstract painting by Balson. Though they were not actually conceived as collaborative painterly objects. Their presentation here instead is a canny workaround; Crowley—an exacting self-critic—would pass on her rejects to Balson for recycling. Instead of brutishly painting over them, he would use the verso for his own painting, sealing up Crowley’s works behind his, like hidden charms, saving her from herself. These two (four?) paintings act in the exhibition, much like the ampersand in the show’s self-explanatory title, as a load-bearing device for the indivisibility of Crowley and Balson. The artistic partnership doubles as a two-person vanguard for geometric abstraction in Australia through the 1940s and 1950s.

The entire centre room is dedicated to this period of work; both Crowley and Balson are concerned with deceptively knotty geometric constructions—all interweaving squares, circles, rectangles, triangles—but equally notable with colour. While they worked closely together in a shared studio from a shared set of formal concerns, they never went as far as indistinguishability; Crowley favoured imprecise edges, her shapes bound by rough slopes that mimic torn paper, atop which single lines irregularly zag. Balson preferred more typically Constructivist geometrics, though his floating planes of transparent colour are still ever-so off, hard yet wobbly-edged. The contemporary response was overwhelmingly indifferent; one critic in 1951 admitted to being stumped. The duo’s works are “so nearly blank that it is difficult to have any but the blankest thoughts about them.” While the critic wanted a new vocabulary, a “special blank language to talk about them,” I can’t help but see them as fun, still fresh. I’m hard-pressed to experience the voiding effect they once exercised. While economical in design, the paint is layered generously without any of the gluttony of impasto. Which might be at risk of becoming mid-century kitsch in less deft hands.

Grace Crowley, (Linear rhythm), c. 1943. Warrane/Sydney, oil on cardboard, Andrew Collection.

Ralph Balson, Constructive Painting, 1946. Warrane/Sydney, oil on cardboard, Andrew Collection.

This exhibition cannot be said to be a general overview of either Crowley or Balson’s painting career. Curator Beckett Rozentals focuses on charting their journey to total abstraction, an evolution of style. There is nothing of Balson’s post-impressionist works before 1938, nor any of Crowley’s academic impressionist works. The flow is smooth, moving from room to room, forward through the decades. The show is certainly a pleasure, generous in the amount of paintings on display, at least fifty or more, many of which have been lent from private collections. I actually went a few times on my lunch break at a loss of anything else to do. Yet the flow itself was almost too smooth. It was far from an organic evolution from Cubism to abstraction (a question much argued over in the late 1930s, including in Australia). Still, abstraction is treated here like a fait accompli, not a proper break. The show’s underlying curatorial approach felt like it was not about Crowley and Balson, or only in name.

Instead, in this show, the two artists became a front for re-telling the standard history of modernism, from Cubism through to post-war abstraction and beyond. In the final room, with the varying approaches to post-painterly abstraction, we arrive at the beginning of “now,” their importance as artists as a proxy legacy for the present, dragging “Australian art” forward through these various steps. This might seem like an anodyne point, but this overarching narrative, as it is encountered here—which can be boiled down as the move from Paris to New York—feels like driving along an imperial highway in a self-driving car, cruising an overpass far above the contours of the ground. Admittedly, this approach is not so much an issue with Balson, who was always a post-national painter. An autodidact plugged into international art developments, he was successively interested in Constructivism from the 1930s, the New York School by the early 1950s, and, later, the European Tachist painters. Arriving from the United Kingdom in 1913 at twenty three, his art had always been unbothered by the idea of Australia. Daniel Thomas (the curator responsible for bringing both Crowley and Balson’s legacy into the hands of the state institutions) suggested in 1967 that they were both painters of “very private experiences, not public nationalistic ones.”

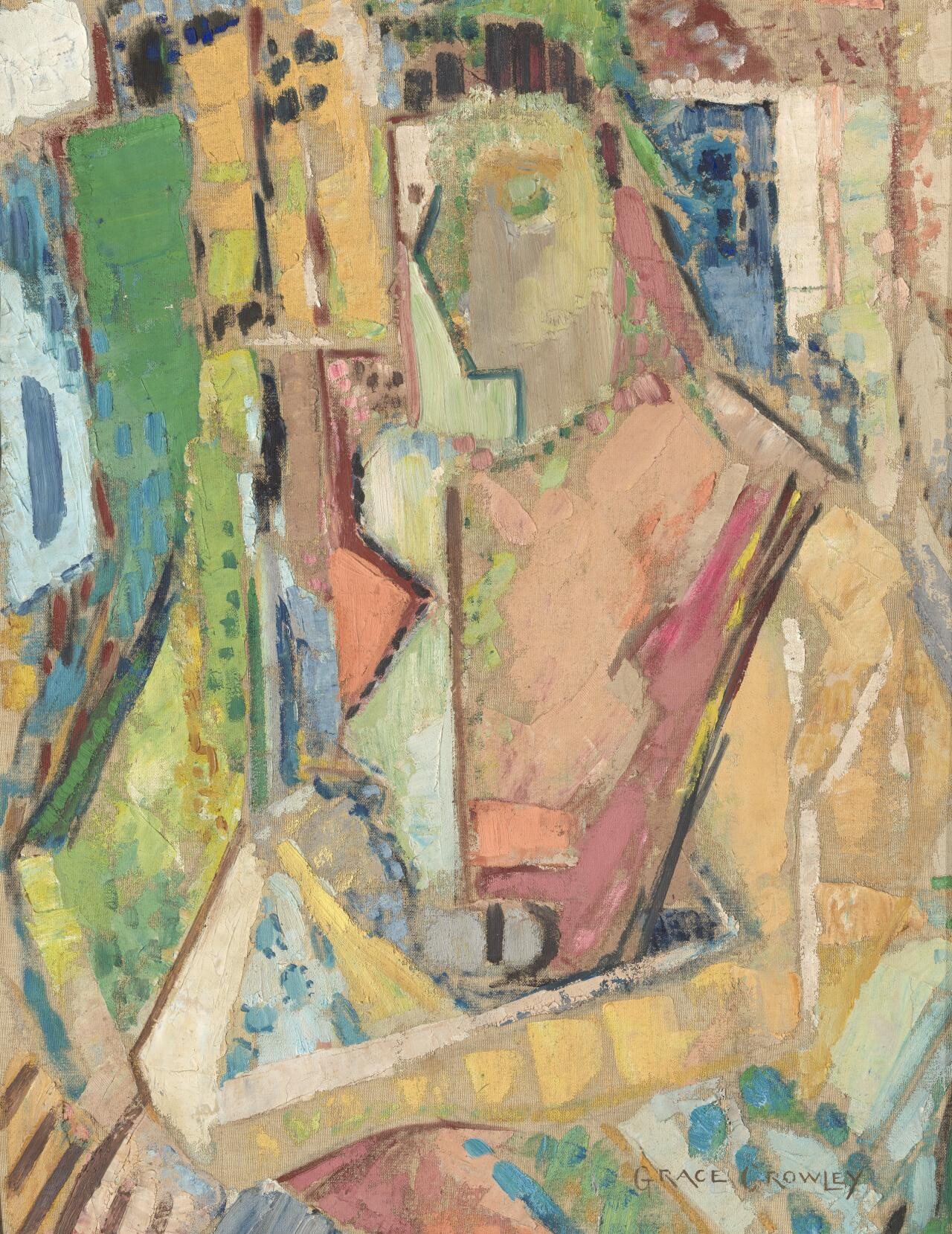

Grace Crowley, Portrait, 1939. Oil on canvas on cardboard, 71.6 × 56.2 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Ralph Balson, (Constructive Painting), 1941. Oil on cardboard, 71.4 × 56.2 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Crowley and Balson had first met briefly in 1922 when Crowley was teaching sketching classes at the Sydney Art School. Balson’s work had caught her eye, and she remembered them as “delicious gems of colour.” Their partnership only began when they were re-acquainted in the early 1930s. Their relationship and the extent of their influence on each other have vexed subsequent historians and curators. The angle here is of mutual support and influence. Most who knew them didn’t quite understand the partnership. Balson was reportedly “morose,” “inarticulate,” a “solid, sturdy, very set up man, not very talkative.” He was essentially an amateur artist, working full-time as a house painter from twelve until his retirement in 1956. His 1941 exhibition of abstract paintings—the first in Australia dedicated solely to pure abstraction, partly re-displayed here in a somewhat inaccessible salon hang—was only made possible as Balson was gifted temporary access to a studio to paint during the day between jobs. Contrastingly, Crowley was described as “delicate, lady-like,” “a bit of a poseur.” A rising figure of the Sydney art establishment, she was a child of the late squattocracy and a recipient of an allowance, so she did not need to work.

For all their dedication to a vivid but thoroughly unromantic conception of painting, Crowley and Balson’s artistic relationship likely held some romantic quality. Yet no one seems to know how romantic. It is possible their relationship was as platonic as their paintings, a purely emotional affair. A pair of clogs is included in the exhibition, hand-painted by Balson for Crowley in his signature blocks of colour…intimate, suggestive. The curator is tight-lipped; beyond the basic biographical details, she blankly offers that “the exact nature of their relationship remains an enigma.”

Eyebrows can only rise at Balson’s discrete occupation of Crowley’s garage at her rural property after his retirement at sixty five (the aged pension allowing him to dedicate time to painting finally) or their trips together overseas. What to make of Crowley’s gift to Balson of Herbert Read’s Art Now on Valentine’s Day in 1935? Or her last work before full retirement from artmaking, the 1962 Self Portrait with Rake (rake presumably in the Hogarthian sense)? Crowley’s alleged final words on her deathbed were “Now I’ll be with Balson.” Mills & Boon (the teacher falling for the student)? A Douglas Sirk movie (the labourer and the lady)? Or, more mundanely, what one art historian opined, “Wheeler Centre-eqsue”?

Of the pair, Crowley has been the most vexing. She ended up self-immolating, sacrificing her career to support Balson. The sculptor Robert Klippel was the only associate of theirs who was candid in making any appraisal of their relationship: “I couldn’t understand, she used to get really angry with me when I questioned her doing this, putting him first all the time, and I didn’t believe in it. I thought she was a really good artist in her own right, and I couldn’t see why he had this precedence.” She has no paintings in the show beyond 1953, demonstrating these downing tools.

Ralph Balson, Pair of clogs, c1940-1945. Painted wood, 10.4 h x 26 w x 9.6 d cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

The show begins in 1928, with Crowley in Paris, footloose and independent. During her four years in Paris, she studied under André Lhote and Albert Gleize, both first-wave Cubists. There is a preponderance of portraits and figure sketches in the selection of works here. While Crowley was a great depicter of feminine disinterest and independence, they can be stiff as stand-alone works. Passages in the studio tableaux Sailors and Models (1928) do contain, in miniature, hints of Crowley’s abstract works with the snaking outlines—the dash of an eyebrow, lips, or curling ship ropes—weaving above pixel-like patches of colour.

The next room begins with works from the thirties, after Crowley’s return to Sydney. She ran a small art school in the city along Parisian principles, and her acquaintance with Balson renewed as he used the studio to paint (he was unable or unallowed to paint at home). In the interim, since their first meeting, Balson had kept active, holding a solo exhibition at the Modern Art Centre in 1932. The paintings are vibrant and idiosyncratic, experimental studio works, with both Crowley and Balson exploring high-keyed colours and distortions of form.

The movement here, with the exhibition weighted at one end by Crowley and the other by Balson, meeting betwixt, seems to suggest a passing of the baton from one to the other, transitioning from Cubism to Abstraction. Crowley argued otherwise. She didn’t think Balson had much interest in her school’s Cubist-derived teachings; she, in fact, claimed the opposite, recalling, “I felt, ʻMy goodness. That man could teach meʼ.” The curatorial emphasis is largely on the pedagogical underpinnings of Crowley, with mention of the “golden section” (via Lhote) and “dynamic symmetry” (via the painter Frank Hinder, who had recently returned from abroad). Much less is made of Balson’s strong interest in Piet Mondrian’s writings. Kilippel complained of the intensity of Balson’s attachment, exasperatedly recalling “the trouble is, all he was obsessed by was, God if I know why, was (Mondrian)…and he was always spouting this stuff all the time. That’s all he talked about.” It is Mondrian’s exhortations against “particular form” that lurks behind the unresolved, off-centre quality that animates the best of his abstract paintings.

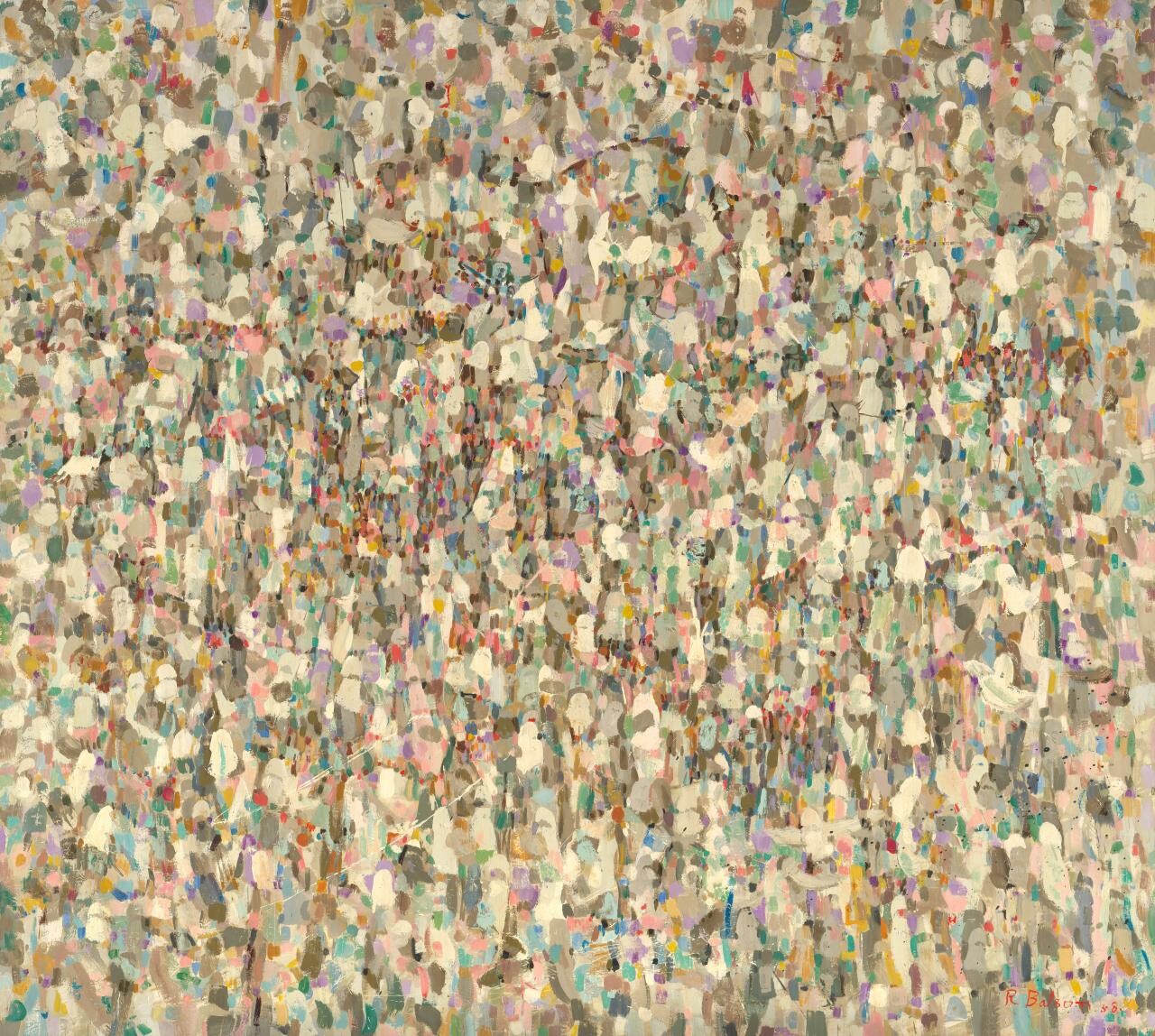

Ralph Balson, Non-Objective Painting, 1958. Oil on composition board, 135.8 × 151.0 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

The exhibition’s second half is almost exclusively dedicated to Balson’s work from the 1950s and 1960s as he embraced formlessness over structure. While Balson never truly became a free, gestural painter, Balson’s interest in New York abstraction in the early 1950s was likely due to synergy and not just trend-spotting. Robert Motherwell claimed Mondrian as the “moral ideal” of Abstract Expressionism, and given this shared importance, Balson likely recognised a solution to shared problems, prompting a re-assessment of his own interpretation. This begins with a trio of small pastel works from the early 1950s, which perhaps not un-coincidently recall Mondrian’s Pier and Ocean 1915 series in their unanchored mass of crisscrossing black marks. Balson’s works continue to unfold from this point on, like a scaffolded collapse of control, pushing a logical sequence further and further along. Balson’s floating squares were reduced and multiplied until his unit of space became the individual brushstroke itself. Non-Objective Painting 1956 is like a static pulse, a slab of single daubs of creamy white, pink, rose, soft grey and teal. The suggestion of explosion is only an effect; Balson allegedly executed these works sometimes at a glacial pace over months, minutes between single brush marks. I want to like his final Matter Paintings, but I find them kind of bad-ugly when seen with all the other paintings in the show. Pushing what little could constitute control in a painting, Balson poured the paint directly on the canvas from the tin—elemental, grim, black gothic slabs of marbled paint. If anything, they anticipate the overblown cosmic abyss of earliesh Tangerine Dream, pre-empting metaphysical hippie-headiness.

Though more subtle, the question of control was also present in Crowley’s abstracts. While Balson was always the more experimental painter, Crowley remained the more accomplished and satisfying painter. She used chance procedures to assist with composition, and her earliest abstracts here, including one of the shared upright paintings, make visible the genesis of her rough edges and darting lines from working models of torn paper, strung string, and dropped buttons. With these working models, Crowley had intuitively arrived at table-top composition—aligning her work with co-current tendencies emergent in painting, what Leo Steinberg later termed the “flatbed picture plane”—also anticipating the drag and drop of desktop editing. Her paintings suggest scattered order, nowhere, virtuality, and an all-in-world space.

Grace Crowley, Abstract Painting, 1947. Oil on cardboard, 60.7 h x 83.3 w cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

For Crowley, the move to abstraction was less natural than implied here. While Crowley was never a landscape painter in the Heidelberg tradition, she had a reputation for portraying Australian farm life, hailed in 1924 as the future of “outback painting.” Even after Crowley returned from France, she re-commenced where she had left off, making sketches throughout the 1930s of rural scenes while living back on the family farm. Crowley went on drawing woolsheds, prize bulls, and favourite horses, still exhibiting as late as 1937 what one critic savaged as “spineless little agricultural scenes.” She unsuccessfully produced preliminary sketches for what would have been grand tableaux of Australian rural life, a synthesis of Andre Lhoté with the local. As a gloss on the pre-existing understanding of Crowley, the exhibition continues to treat these works, as in the 2006 National Gallery of Australia show Grace Crowley, Being Modern, as “aberrations” on her path to pure abstraction. Their complete absence from the exhibition is a dismissal, as a vestigial tendency of little relevance.

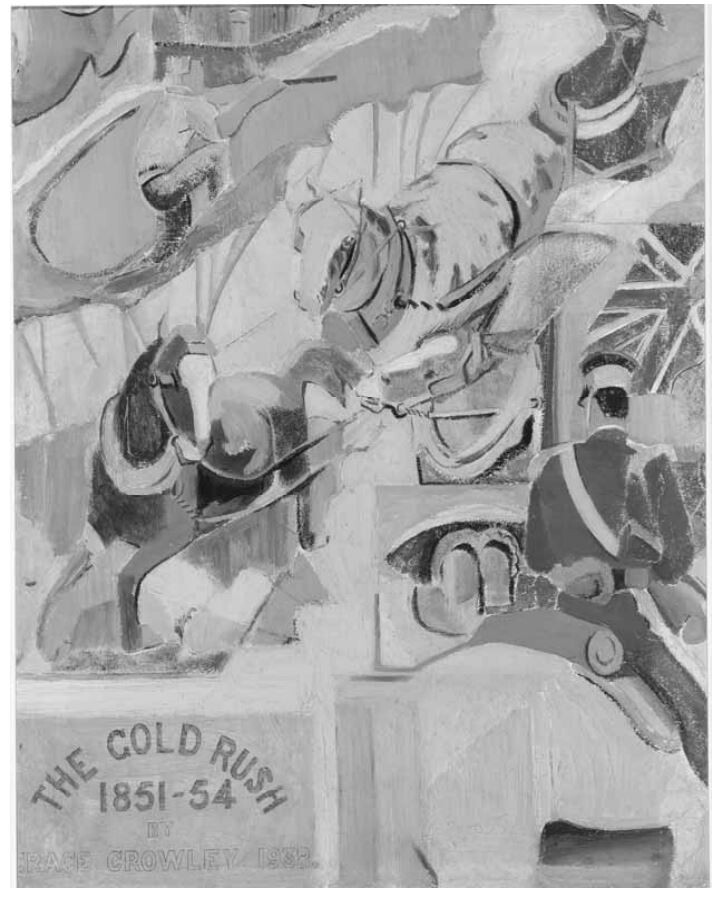

Grace Crowley, The Gold Rush 1851-54, 1938. Oil over pencil on cardboard, 60.2 x 47 cm, private collection.

It is telling that for all the revelations of hidden paintings that accompanied the show (an early Balson abstract in the show was also discovered behind a Crowley painting in preparation for the exhibition, forming part of the media campaign, with newspaper articles and television slots, the conservation process treated to a rather clunky multimedia component included in the show), there is, in fact, another painting hidden here. Yet, it is also deemed unworthy of either display or comment by the curator. Abstract painting with gold and silver ribbon (1941), one of the earliest surviving abstracts by Crowley, has behind it the fragment of a large 1938 work, a history painting, The Gold Rush (1851–54). An entry for the Commonwealth Sesquicentenary Prize, it is a fragmented, collage-like portrayal of “Red Coats,” the Union Jack, galloping horses, and workers hauling grain sacks and dust. I tried to peer behind to see if it was there. Honestly, I couldn’t tell (I did wonder how advanced the gallery security set-up was, whether all the paintings were booby-trapped with electronic alarms, or if it was only reliant on the painted lines on the floor and the wandering security guards who advised me of the said lines) the owner may have long had it removed. Still, old fashioned, musty, distasteful. It sits uncomfortably with the image of Crowley, the cosmopolitan, post-national modern established in the opening Parisian room. Indeed, the opening of the exhibition, a trio of female nudes that begins with Olga 1928, whose subject is an African studio model who worked for Lhote, reads like an explicit disavowal of a masculine Australian identity. The exclusion here of Crowley’s Australiana makes sense if we accept a limiting view of Crowley’s path to abstraction solely through Cubism, which implicitly suggests a rejection of Australia. Crowley’s “importance” is espoused in the show on stylistic grounds and at a larger symbolic level. Yet this urge for resemblance and reflection is a fun house mirror, risking distortion and endless repetition. I was left wondering whether it was not equally possible that it was Crowley’s failure to successfully synthesise “Australia” with Cubism that instead explains the appeal that total abstraction offered.

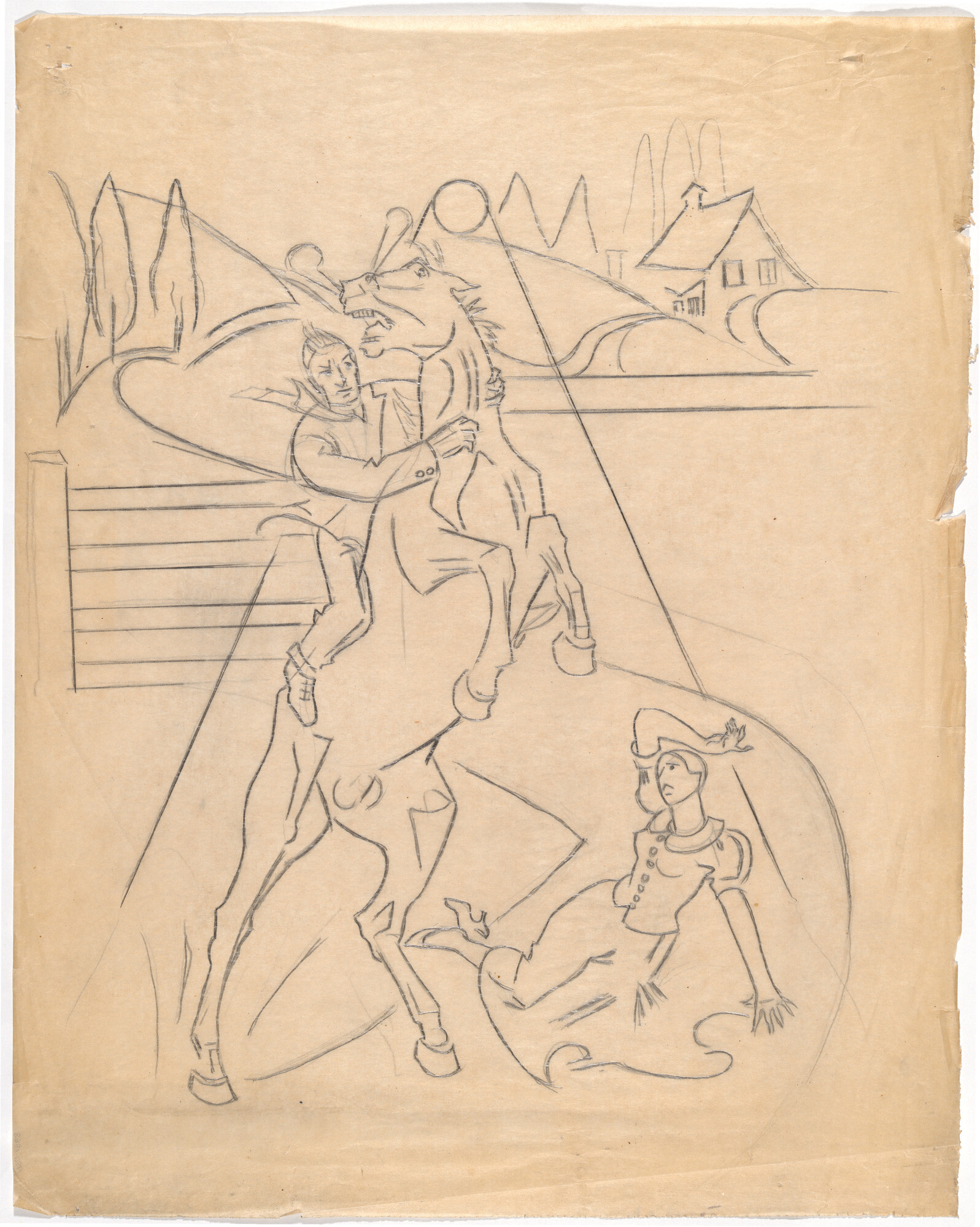

Grace Crowley, not titled (Male figure on rearing horse and female figure on ground), c. 1937. Drawing in pencil, 43.2 x 34 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

To hazard further and final speculation, part of Crowley’s dedication to Balson at the expense of her own art, her belief in his “genius,” might have been a warped act of gratitude. A sketch from this period is not included in the show. It stands out for its drama, which is notable as Crowley was always a painter of the serene. A damsel in distress cowers beneath a bucking bronco, which a man in a suit is wrestling to stop from stomping the damsel to death (of her time spent back on the family farm in the 1930s, caring for her ailing mother, she only remarked, “I wanted to die”). Is this a glimpse into the interior of someone otherwise closed? Embracing abstraction resolved an intractable pictorial and personal issue for Crowley, who, having been either a studio or outback painter, highly accomplished but never a “visionary” painter, so to speak, was saved by Balson from listlessly drifting into becoming a kept modern, with Archibald submissions, mural work and Government commissions, like some of her associates. An explanation Crowley herself gave for the move into abstraction was simply that as she lost her school space in 1937 and no longer had room to pose a nude model, it was as if she had run out of things to paint. Either way, abstraction provided simply a licence to finally just paint.

Jarrod Zlatic is a critic and musician from Melbourne.