Goya: Drawings from the Prado Museum

Diego Ramírez

Francisco Goya spent much of his painting career making royal commissions, transitioning to more independent pursuits later in life, including satirical and phantasmagorical portraits, during times of disease and war. His art announces the advent of modernism and documents a historical turning point in the eighteenth to the nineteenth century, when ideals of the Enlightenment and the Napoleonic invasion brought a state of crisis to the Spanish monarchy. Goya: Drawings from the Prado Museum, showing at the NGV International brings together over 160 works on paper that chart Goya’s grotesque sensibilities and how he deploys obscenity to articulate satirical critiques. These drawings and etchings include war scenes, portraits of the aristocracy, the working class and witchcraft—most of which are popular topics in contemporary art today, creating a receptive environment for his practice.

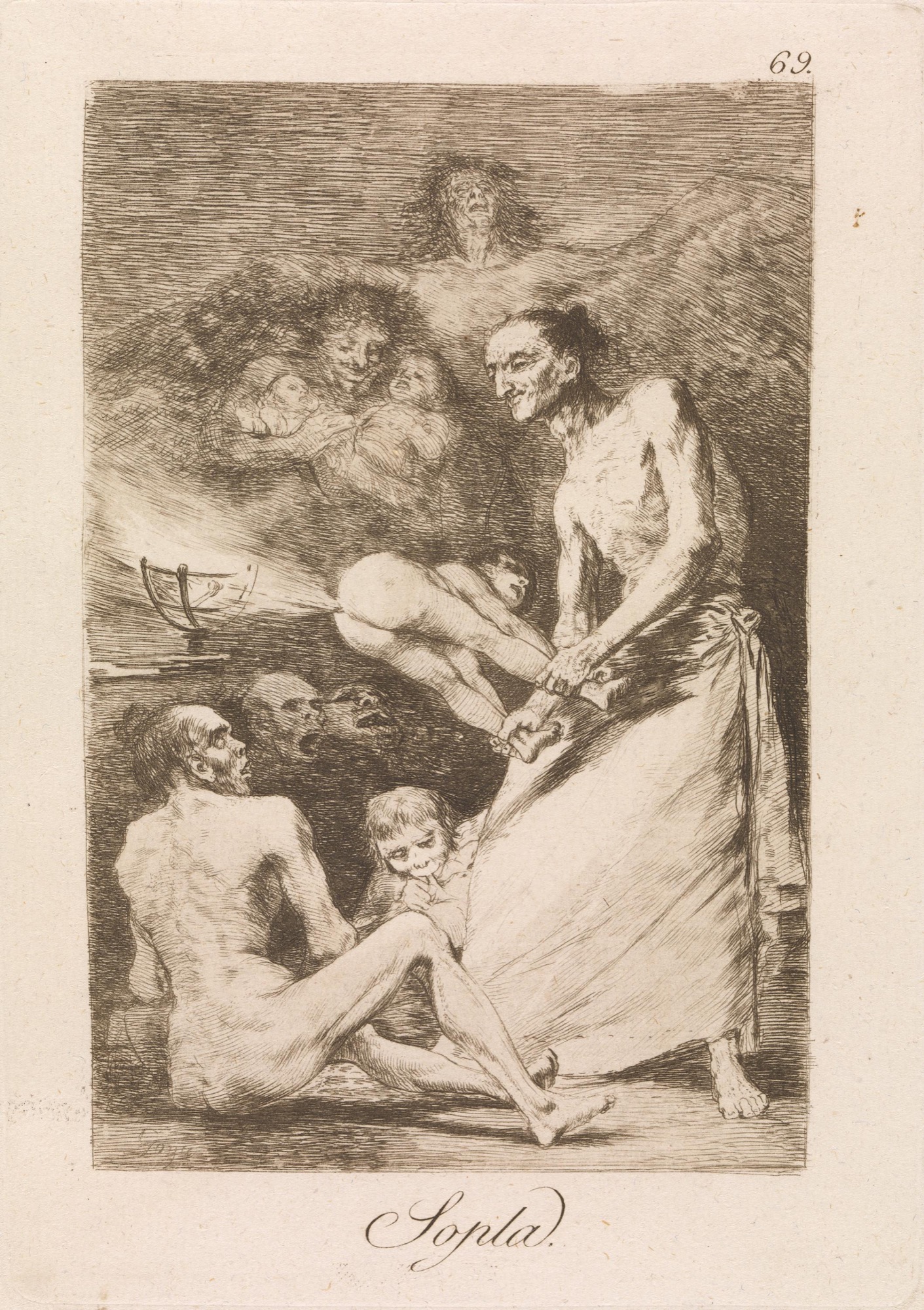

We often read Goya’s work through a socially conscious lens, encouraged by Goya’s own preoccupation with “political issues”, despite the intensely gothic scenery that populates his oeuvre. While it is true that he used satire to political effect—and that he offers invaluable documents of war—it is hard to ignore the delirious quality of his imagination and its correlation with the onset of an unidentified illness that caused him to hallucinate, as well as the psychological scarring of conflict. The disturbing textual quality of his practice is thus one of his most important contributions to visual culture, often overshadowing his Enlightenment “virtues”. We love reducing art to a presidential campaign (the good artist changing a bad world), but it is the mysterious energy of art—with its fractures, distortions, and inconsistencies—that endures. Today we tend to measure Goya as a goody two shoes. But how can this assessment explain the vigour of Sopla (Blow, 1797–1798), which shows a person lighting a candle, by holding a baby that is blowing fire with a fart, while death looms in the background?

Indeed, Goya’s predilection for ghastliness permeates his etchings Los Caprichos (The Caprices, 1797–98), which capture a shift in European representations of evil, in a suite of etchings dedicated to social satire, superstition and monsters. This body of work documents how Western iconography moved from showing perversion as a physical feature— something seen from the outset (monsters)—to an internal state with decreasing corporeal deviations (pathology). It is easy to appreciate how the atrocities of war in tandem with a post-supernatural predisposition would eventually lead to the realisation that badness is a humanist problem—not a theological one. Literary works of the Enlightenment precede this evolution, such as John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), where Satan is a state of mind rather than pure appearance, and signals the cultural arrival of psychoanalysis in the twentieth century.

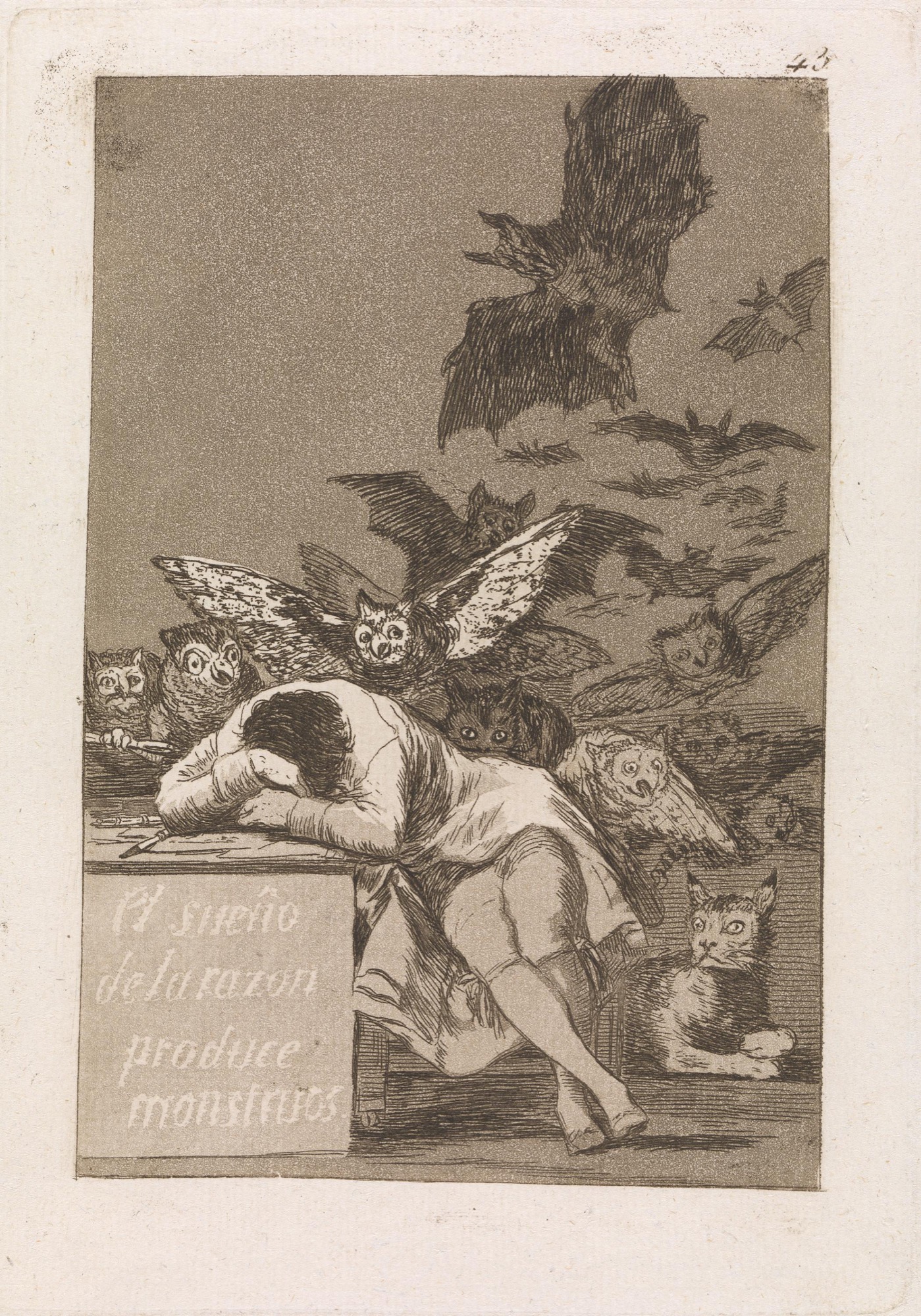

Goya’s famous etching El sueño de la razón produce monstrous (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, 1797–98), a self-portrait of nightmares preying on the artist, epitomises this move towards a greater understanding of inner states by codifying monstrousness as an internal turmoil, rather than a bodily manifestation—such as the amalgamations of animals used to show the devil in the Middle Ages, where painters would imagine demons by combining different animal parts. While a decolonial makeover could help Goya’s museum didactics, considering that Mexico was fighting for independence from Spain during his lifetime (eased by the timing of the Napoleonic invasion), it does not detract from his importance in art history.

I was ready to visit Goya: Drawings from the Prado Museum, having prematurely found in it some of the issues I am interested in, when we entered lockdown six point oh-no. As I considered different approaches to resolve this inconvenience, it occurred to me that it would be hysterical to write a satirical text (very Goya) using the show as a springboard to discuss social contexts, without visiting the exhibition (typical). The idea was to set up a fictional scenario for this review, where I gathered my “career advisors”, who would recommend that I “listen to Bernie Sanders” and “buy a Tamagotchi”. I did start this fictional review but lost steam halfway through, so I cut most of it. Except for the following passage—which is poetry, really:

I trawled the Internet for dirt to post the receipts—what do you mean Goya didn’t have Facebook—and become Saturn, turning the Spanish Master into my yummy son. Nom, nom, Frahn-SEES-ko … you are so succulent and delicious. However, a strange memory slowed me down, for it incited doubt like an invasive thought, which made me feel torment, evoking El sueño de la razón produce monstrous. I suddenly remembered how some of my colleagues got “so fucked up” over the weekend, that they met the ghost of “Goya”, who gave them a recipe for paella (I know they were hallucinating because it had tofu on it). I am straight edge (like Fugazi, y’know), so I spent the night sipping water with a lemon wedge.

As I was reaching the bottom of the glass, it struck me that these recreational activities are sponsoring a Drug War in developing countries, on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, but their right to party is more important than the welfare of Juan and Maria. In the context of their intensely public allegiances to social change, this behaviour is a little bit ironic—just a tiny bit, like the drop of saliva that fell on my glass, when I shockingly realized most of us do not engage with social work, beyond reading art monographs themed “Social Work”.

II

Now that I have opted out from trolling, I am stuck with the online assets offered by the NGV on their website. Understandably, there is not much bespoke content to hold onto, aside from some images that have been organised by series or mediums, with contextual information that emphasises the moral value of Goya’s work. One of the most illustrative resources is a hi-definition “promotional” video that shows the staff explaining the contents of the rooms, with cross-cuts of installation shots. The camera is tracking and panning the art, using wide shots, medium shots, and close-ups at fast speed. The video lasts for only two minutes but it feels densely packed with videography intended to make the contents of an empty museum bearable to watch at home. I hope the need for this type of documentation leads to a genre of sorts, and we see increasingly saturated promotional videos in museum websites—picture the Michael Bay of institutional videography (it could be you).

There is also a detailed essay featuring some of the most important works in the exhibition, explaining their mediums, and noting that Goya was satirising his contemporaries under the inquisition. Goya’s willingness to burn bridges all the way to the morgue is inspiring, along with the fact that he started drawing at 48, before moving onto the Pinturas Negras (Black Paintings) in his 70s, which include Saturno devorando a su hijo (Saturn Devouring his Son, 1819–23). One can also watch a random video clip of a tattoo artist carving their mum’s leg with this painting, which is high quality content in my books. One big problem with blockbusters such as this, however, is that the money spent on frame insurance alone could help a myriad of local artists. Still, Eurocentric cultural policies do not devalue the power of Goya, whose vibes have the undoubted potential to turn year 12 students into sulky artists.

El sueño de la razón produce monstruos is full of these vibes and it has its own page on the NGV website, filed alongside images of witches, and the Sabbatic Goat, from the Los Caprichos series. The work shows the artist sleeping on his desk, where the night haunts him, in an onslaught of owls, bats and black cats. His pose suggests that he fell asleep whilst writing a letter or a manuscript, made obvious by the title inscribed on the etching. The way Goya leans on the surface of his desk—anxiously covering his head—also conveys that he is hiding from the creatures that torment him. The work bears a strong semblance to The Temptations of St Anthony, a painterly genre that depicts demons haunting Saint Anthony. A fifteenth-century engraving by Martin Schongauer is one of the most famous examples of this tradition, which shows a horde of grotesque and imaginative beasts pulling St Anthony’s body. However, many artists created their own interpretation. These included Max Ernst, who made an outrageously ugly version that strangely resembles Google’s DeepDream.

The main difference between El sueño de la razón produce monstrous and an image like Martin Schongauer’s The Temptations of St Anthony, is that the former depicts these fiends as a mental mirage, while the latter portrays them as actual beings. This relocation of evil from the body to the mind is in the physicality of the creatures themselves—for the demons in Schongauer’s are gruesome amalgamations of living creatures, while Goya surrounds himself with undisturbed animal forms. Unlike the many caricatures that populate his oeuvre, this piece represents wretchedness as a lack of reason, a malaise of the mind, without troubling anatomical features. This pictorial shift precedes depictions like Al Pacino in The Devil’s Advocate (1997) or Netflix’s Lucifer (2016–), where the fallen angel—often a symbol of corruption—is depicted as a human with a pathology. This is a more realistic legacy for Goya, alongside the historical value of his visual impressions of war and experimentation with materials, rather than the do-gooder narrative that permeates his practice today. I am not sure if Spain signed an independence treaty with Mexico after looking at one of Goya’s pieces, and going “Ay Dios mío, we are bad and want to be good”, but he made formidable pictures. Some of which I am going to see IRL, once lockdown is over.

Diego Ramírez makes art in different mediums, writes about culture, and labours in the arts.