Gordon Hookey: A Murriality

Joel Sherwood Spring

First, it’s important to place myself in relation to Wanyi artist Gordon Hookey’s first survey show, A Murriality, currently on view at UNSW Galleries. I am writing from the unceded lands of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, who have practiced their sovereignty and law on this land, commonly known as Sydney, since the first sunrise. I acknowledge their endless and continuous care for the Country I was born on and call home and, in doing so, pay my respects to the Gadigal people, their ancestors in their struggles through frontier wars, and their Elders present and future. It is upon their lands that we undertake our work and lives; stolen lands for which a treaty or sovereign agreement has never been negotiated.

Upon entering Hookey’s A Murriality, which spans thirty years of the artist’s practice, you are met with the artist’s perpetual call to “never ever forget!” whose land you’re standing on. Installed alongside a traffic sign ordering the audience to stop and reflect, this form of acknowledgment acts as a reminder of where you are. Comments similar to these are routinely expressed within our institutions and at public events. Offerings of “Welcome to Country” from the First Peoples on the places we work, live and meet are commonplace, and important protocols that recognise time-honoured traditions connected to these places. Often, within the University, this welcome is taken as an empty custom and an acknowledgement, often rushed, like the one I have given, as an equally performative form of political correctness. But what is offered in the Welcome to Country and reaffirmed in our acknowledgements is an opportunity to embark in a sovereign relationship on sovereign land.

We all understand that people lived (and prospered) here before the arrival of the First Fleet and the formation of the towns and cities we now inhabit. We all understand that these peoples had their lands, livelihoods and even lives, stolen (wrongfully and unlawfully, as agreed by the High Court of Australia in Mabo v Queensland in 1992). Hookey’s work attempts to place us within a political history in which we might better understand how blak voices continue to be silenced and then appropriated.

The title A Murriality asserts a clear and unique sovereign voice and subjectivity: a Murri perspective on Indigenous history and resistance to ongoing colonisation, and its impact on Indigenous political and cultural life-ways. Hookey’s choice in offering “A” Murriality as opposed to “The” Murriality creates a space for deeply located political discussions, such as the 2004 Palm Island death in custody, rampant urbanization of natural habits in Brisbane and the continued erosion of Native Title by both federal and state legislators.

Printed on the wall by the entry to the main exhibition space is something like a disclaimer, or a content warning, advising those on entry:

This exhibition contains adult content including very strong language. Some artworks deal with racism and feature hate symbols understood as an expression of antisemitism and white supremacy.

This statement is not dissimilar to the “emotional preparedness guides” supplied to attendees of the Philip Guston Now exhibition currently on show at the Boston Museum of Fine Art. These likely well-intentioned gestures often come off as reactionary, which leaves me asking: Who exactly is this for? Hookey’s work is often directly literal in its message and, coupled with the extensive didactic texts provided by the curators, it’s hard to imagine the need for such a warning. The assumption that those who would come into contact with Solidarity/You Are Here (2021) in Meanjin at the Invasion Day protest, and those visiting UNSW galleries are from different groups makes sense, but this statement speaks to a familiar fragility. Inevitability, a protest banner cut to reduce wind resistance sits in a gallery.

365 x 265 x 50 cm. Collection: The University of Queensland, Brisbane. Photo: Rhett Hammerton. © Gordon Allan Hookey / Copyright Agency, 2022.

A disclaimer might be relevant if it spoke to images of war and violence, of which there are plenty in Hookey’s work. He has long communicated through painting the violent realities that still play out for Indigenous peoples today. A warning also seems to be thematically out of line with the work and the exhibition as a whole—a bureaucratic and administrative structure making itself present before a show with subject matter that speaks directly to histories of institutional injustice and systemic overlay.

Is this an attempt to curb some potentially bad optics downstream? This kind of precaution has a lot to say about how representation functions today. Our reality has become a circulating system of images stripped of their context: a phenomenon that one assumes is key to the success and distribution of ideas through protest banners themselves. Hookey has understood this for a long time, and it’s evident across the entirety of the show.

When someone looks at an artwork they take with them their whole life, their screens of socialisation and they will look at that artwork through their experience … a lot of time they will blame the artist for their interpretation.

- Gordon Hookey

As a part of A Murriality, Hookey was commissioned, with support by the UNSW commissioners circle, to paint nine new artworks styled after and presented as protest banners. Their literal material and the way they have been installed provide a double reading into how political issues and Indigenous cultural life and production are interdependent. What is always remarkable about Hookey’s work is the sheer density of information he is able to skilfully relay through his paintings: he combines text with figurative scenes that are often caricatures of political figures, which rely on narration and are often clearer when read aloud. Given that political gatherings and protests today are mediated through images, the protest banner is the vehicle of transmission for witty puns and quips that present the political position on an issue. I strongly recommend giving yourself enough time to read the works through in their entirety.

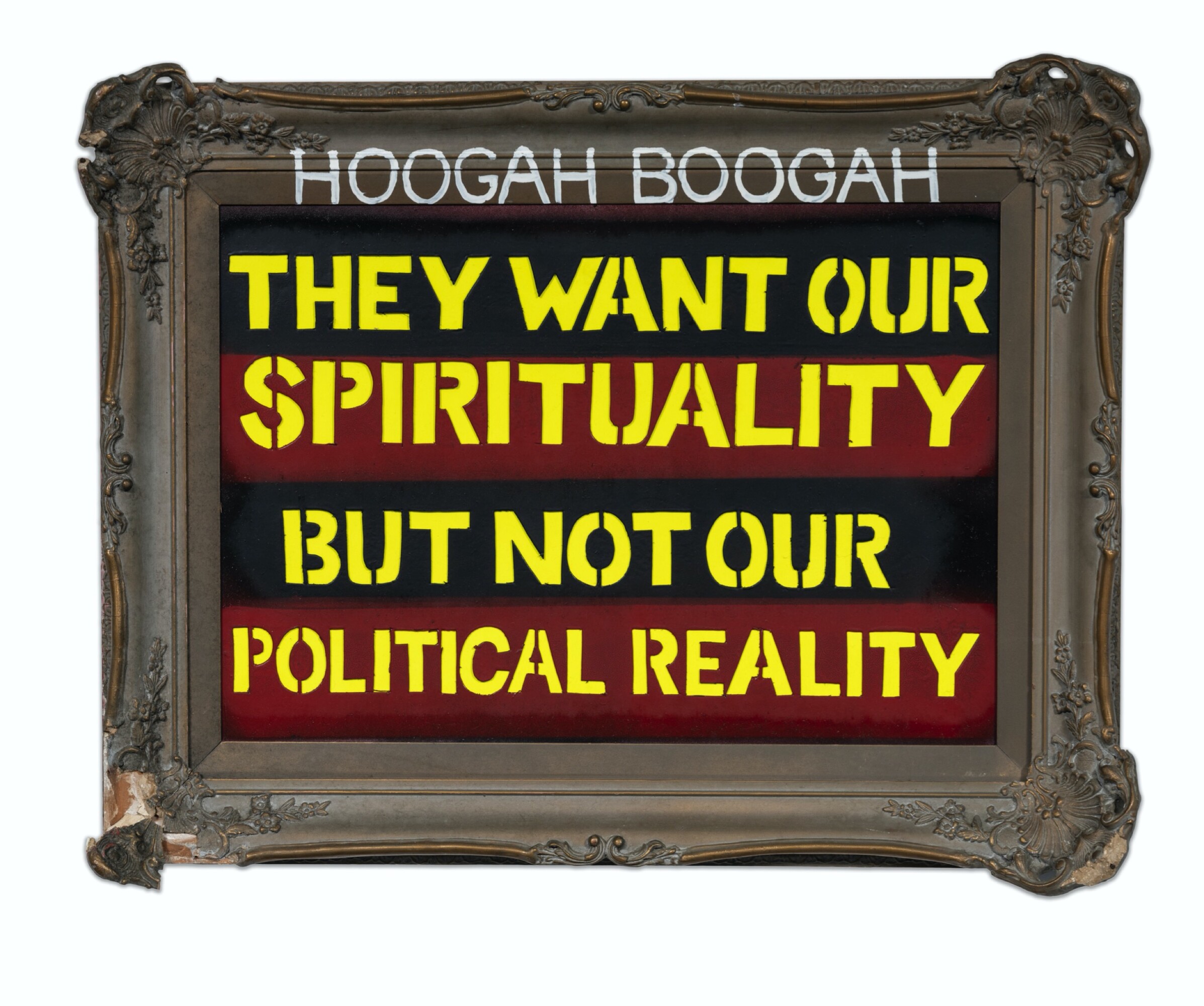

Hookey’s work also touches on how our instinctive judgements about misinformation in the context of culture wars, both locally and globally, fall short when confronted with a real war—there are references to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and genocide in Lutrawita/Tasmania. The banners also speak to land theft, cultural theft, housing affordability and Trump. The double-sided nature of these works articulates the tension underlying visibility and representation succinctly put in the stencil piece hoogah boogah (c. 2005): “THEY WANT OUR SPIRITUALITY BUT NOT OUR POLITICAL REALITY”.

Within the larger context of the moralising turn of art and art institutions globally, these nine new commissions represent to me an interest in, and a return to, craft. This exhibition sits within a larger global context and trend that could be tracked to the first presentation of Murriland in 2017 (Documenta 14 in Kassel), which has seen the very necessary inclusion in major biennials and art fairs of marginalised perspectives, and Indigenous and black artists. With this reorientation comes a fixation with the stuff of othered cultures, archival resurfacings and the celebration of traditional practices. The contemporary reality of Indigenous peoples in so-called Australia for the past three decades (or even as far back as 1938) has been protest. Personally, as a Wiradjuri man born in Sydney and raised in and around Redfern, I’ve made more protest signs and banners with my family and friends then carved timber tools/objects. This is the reality and regularity with which Indigenous communities must take to the streets to seek justice.

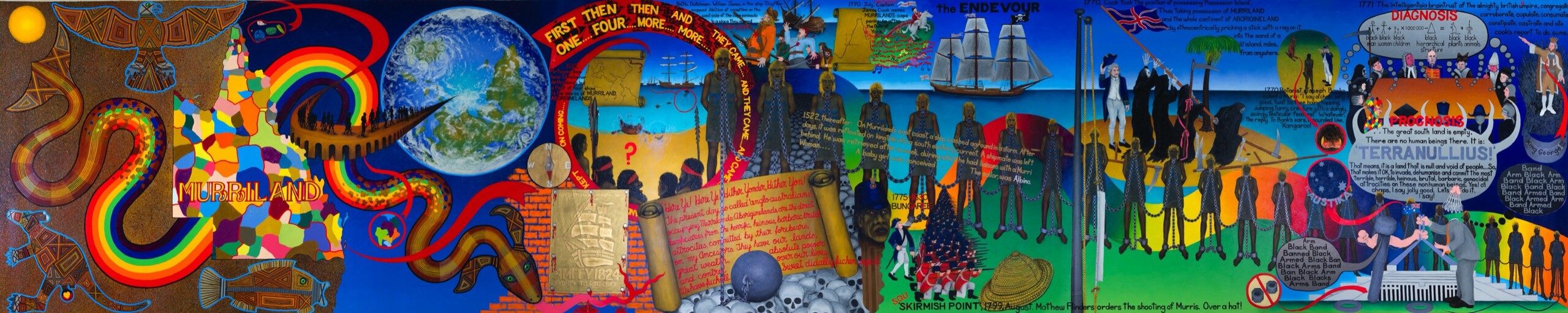

Murriland!, commissioned by Frontier Imaginaries for Documenta 14 and displayed in Kassel in 2017, is a large wall banner of oil on canvas that stretches the length of the main exhibition space. This Murriland! mural neatly lays out Hookey’s method of deploying the banner as a tool of representation and education from a Murri perspective. It plots the trajectory from the dreamtime through geologic and cartographic histories and ongoing colonisation, interpolated by local and global events that produce twists and turns in the narrative. A statement somewhere towards the end of the snaking story marks the point at which the British empire declared (“diagnosed” in Hookey’s words) Australia “terra nullius”, thus wilfully erasing 1,000,000 Black men, women and children. Within Hookey’s work is an understanding, felt through Indigenous cultural production for the last 250 years, of the risks of making oneself legible in this place. This is the risk of using the tools at hand to inscribe oneself against a regime of inscription.

A Murriality then, thought of as a method rather than a thematic, proposes a refreshingly joyful, lyrical and understandably cynical inquiry into an aesthetics of protest and representation. It is one that reiterates the central concerns of generations of Indigenous people across the country. This exhibition takes place at a time of global questioning of institutional forms. Decolonial movements, and movements such as Stop Black Deaths in Custody, Black Lives Matter and those calling for a questioning of where funding comes from within plutocratic neoliberal systems all press us to ask what we can do with these “problematic” institutions. A Murriality in its plurality calls for a diversity of approaches to representation of sovereignties in art, which is to say there is a space for a sovereignty that is moral, but there should also be space for articulations that are immoral or offensive—although it could be hurtful or upsetting to some people, there should be space for work to play with taboos. And, aside from that, we should have space for art that does not take into concern moral considerations at all. Indigenous perspectives, Murri, Koori or collectively, have never been able to retreat into a frightened way of being.

Joel Sherwood Spring is an artist and educator based on Gadigal Country.