Future Eaters

David Wlazlo

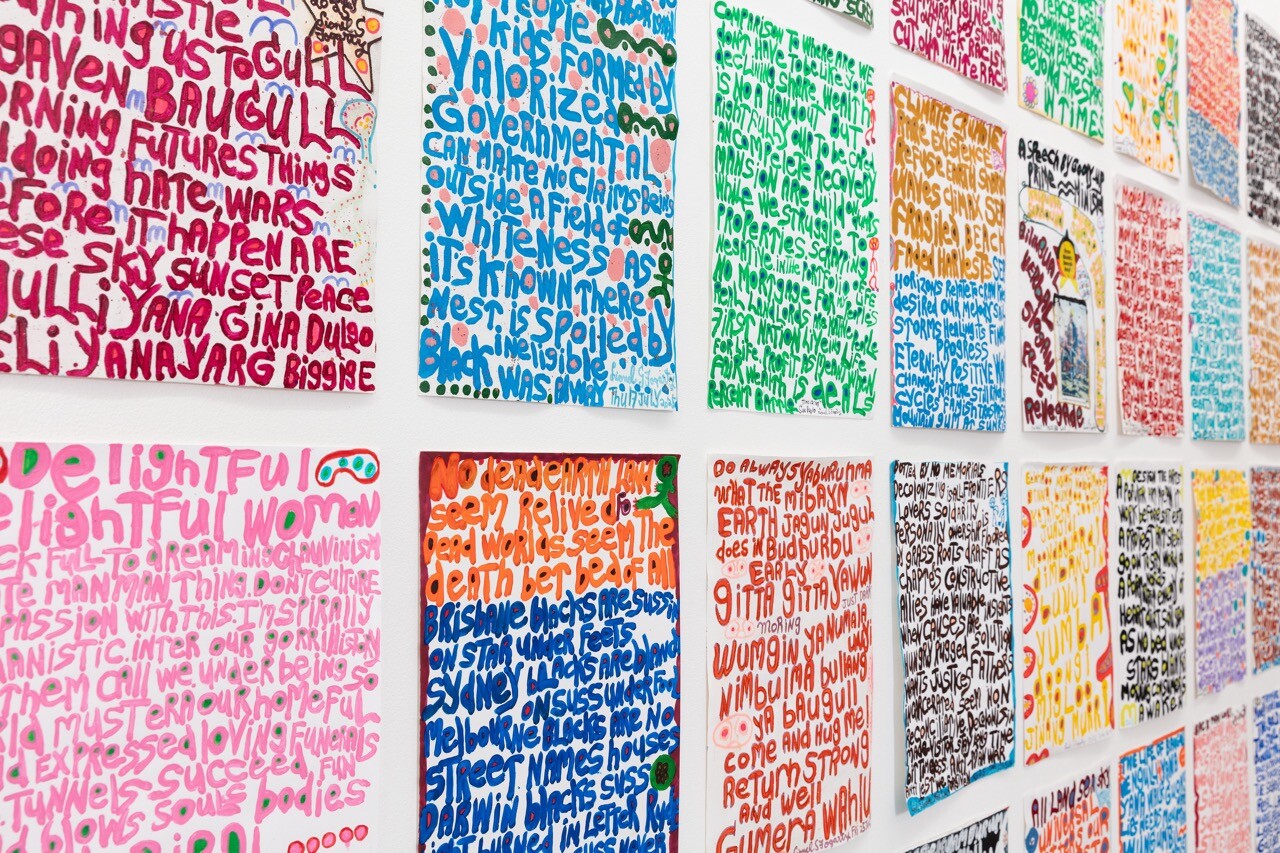

Asking the viewer to consider sculptural responses to our technological present, Future Eaters presents a series of works that are diverse, divergent, and in many ways reductive of the ways technology is involved in our lives. Technology here—like sculpture—is equated with hardware. Of course this is a ‘common sense’ understanding of the technological, but as a premise for a show it sits uneasily with the other, more interesting question: what will the future think when it looks back at 2017?

Seeming to counter the claim made in last year’s Sydney Biennale (whose title “The Future is Already Here, It’s Just Not Evenly Distributed” was a quote from science fiction writer William Gibson), Future Eaters suggests another kind of ethics, one that goes beyond the technological manifold of globalisation toward a radical openness to the future as other. The Future Eaters is the title of a 1994 book by Australian author Tim Flannery, suggesting that current environmental management practices are unsustainable and arguing that we need to re-think our relationship to our resources. Will a future that glances back toward our excesses judge ours as a decadent, narcissistic society that did too little to preserve the planet and guarantee the human future? There is a profound sense of self-doubt, self-critique and introspection in this thought that is not matched by a lot of the work in the show, and as a result the curatorial bow seems a little overdrawn. However, if this exhibition is simply about the future of sculpture and the exhibition, then it becomes more coherent at the expense of its more profound implications.

Nina Canell’s series Brief Syllable (2016) presents fragmentary slices of undersea communications and electricity cable encased in resin. They function like archaeological specimens, cut off from the network they represent. Their materiality as copper cables and their legibility within our communications networks underscores their fractured presentation.

A similar idea is found in the reconstructed undersea pipes of Lewis Fidock and Joshua Petherick. Contrasting with Canell’s ready-made cables, these pipes are elaborately and exactly fabricated by the artists, giving a technical edge to the work. This edge is one of artistic representational labour and its futility (especially in the age of 3D-printing and not even mentioning the ready-made), and it is one shared by a number of other works in the show. For instance Hany Armanious’s Le Nez (2010) recreates in styrofoam a leaf-blower suspended in a bronze frame, and Guan Xiao’s Rolling Beating (2014) represents a car tire and drum-sticks in bronze.

To a lesser extent Alex Israel’s Booties and Glove (both 2016) and Aleksandra Dumanović’s Substances of Human Origin (Pose 1, 2, 3) also share in the traditional sculptural practice of representing one material with another, and there is a sense of the alchemical skill of the artist—for these technicians are undoubtedly skilful—which alternately leaves you satisfied and not.

Hannah Donnelly’s work participates in this trend but in a far more interesting way. Bark/ives (2017) takes the bark of a paperbark tree, processes it with berries from a lilly-pilly plant, and then elaborately re-creates the same paperbark as before. Appearing small and humble next to the other work, it brings to mind Phillip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and its obsessional android reproductions of farmyard animals. By linking technology not to alchemical transmutation but rather to a reproduction of the pre-existing and natural, Bark/ives is probably the only work in the show to match the profundity of the curatorial premise.

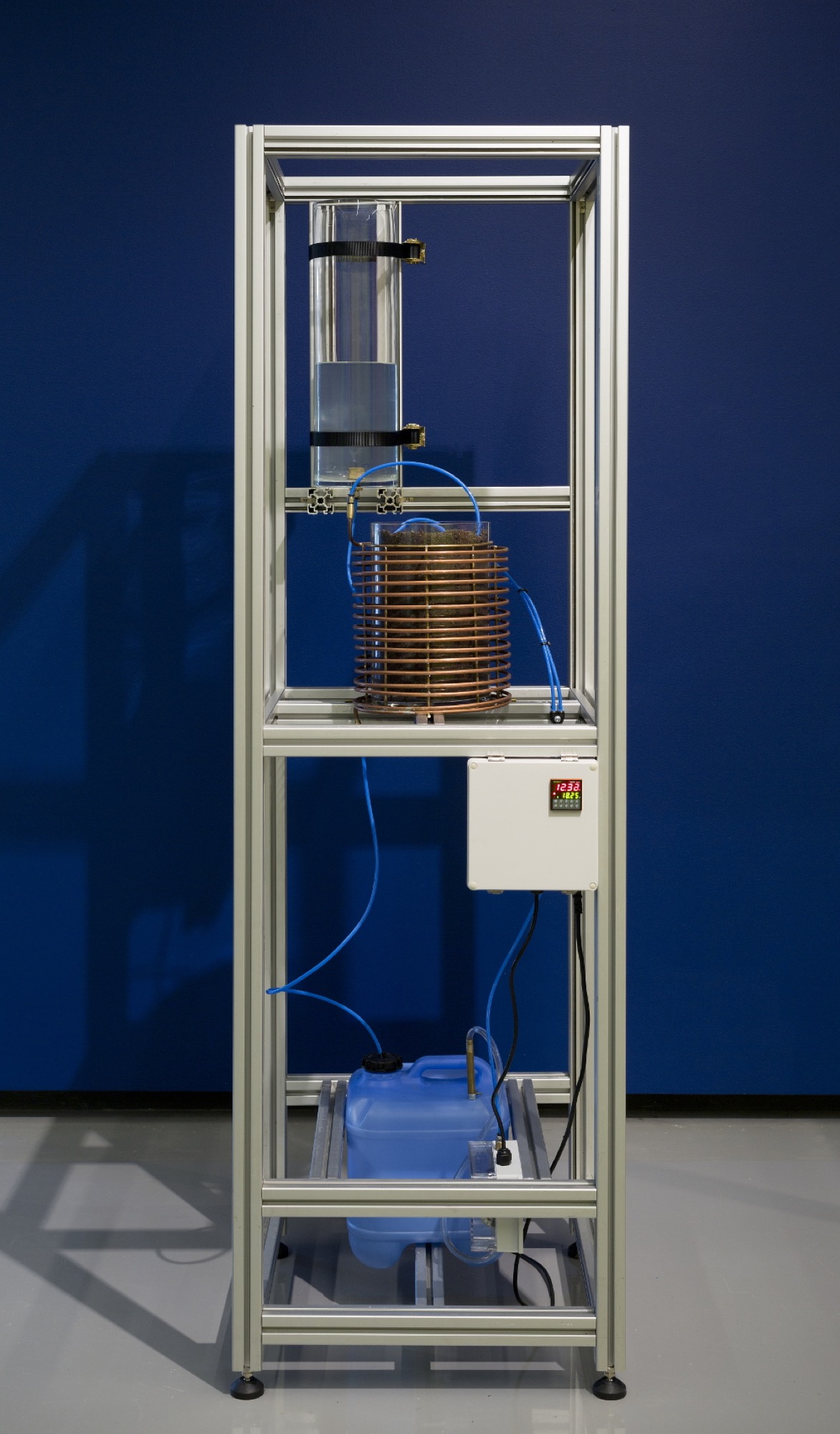

Another artist who works with natural processes and materials is Marley Dawson, whose three laboratory rack pieces illustrate some of the biodynamic principles of Rudolf Steiner. Part batshit crazy, part common sense, these principles involve the burying of animal heads with oak bark in their skulls, and filling a cow horn with its excrement for a year and then diluting the mixture. These processes are said to aid in the production of healthy soil or humus, and anyone who has ever had a worm farm or compost heap won’t find it too hard to believe (but still a little weird on paper). Whatever side of the fence you are on with biodynamic farming, Dawson’s work’s 505, Stirrer/Vortex/Chaos, and 500 (all 2017) represent these processes through scientific structures that are becoming familiar sights in contemporary art: aluminium racks, electric motors and digital timers. All of these suggest a scientific detachment and an autonomous system of a biodynamic process as transformational as the other more traditional sculptures.

Some more abstract sculptural forms are found in the work of Mira Gojak and Benjamin Armstrong. Gojak’s work suggests three-dimensional line drawing, and Armstrong’s work implies a connectivity between ceiling and floor reminiscent of the biological computer hardware in David Cronenberg’s 1999 film eXistenZ. Both artists are given their own room, almost protecting their subtlety from the direct legibility of most of the other work.

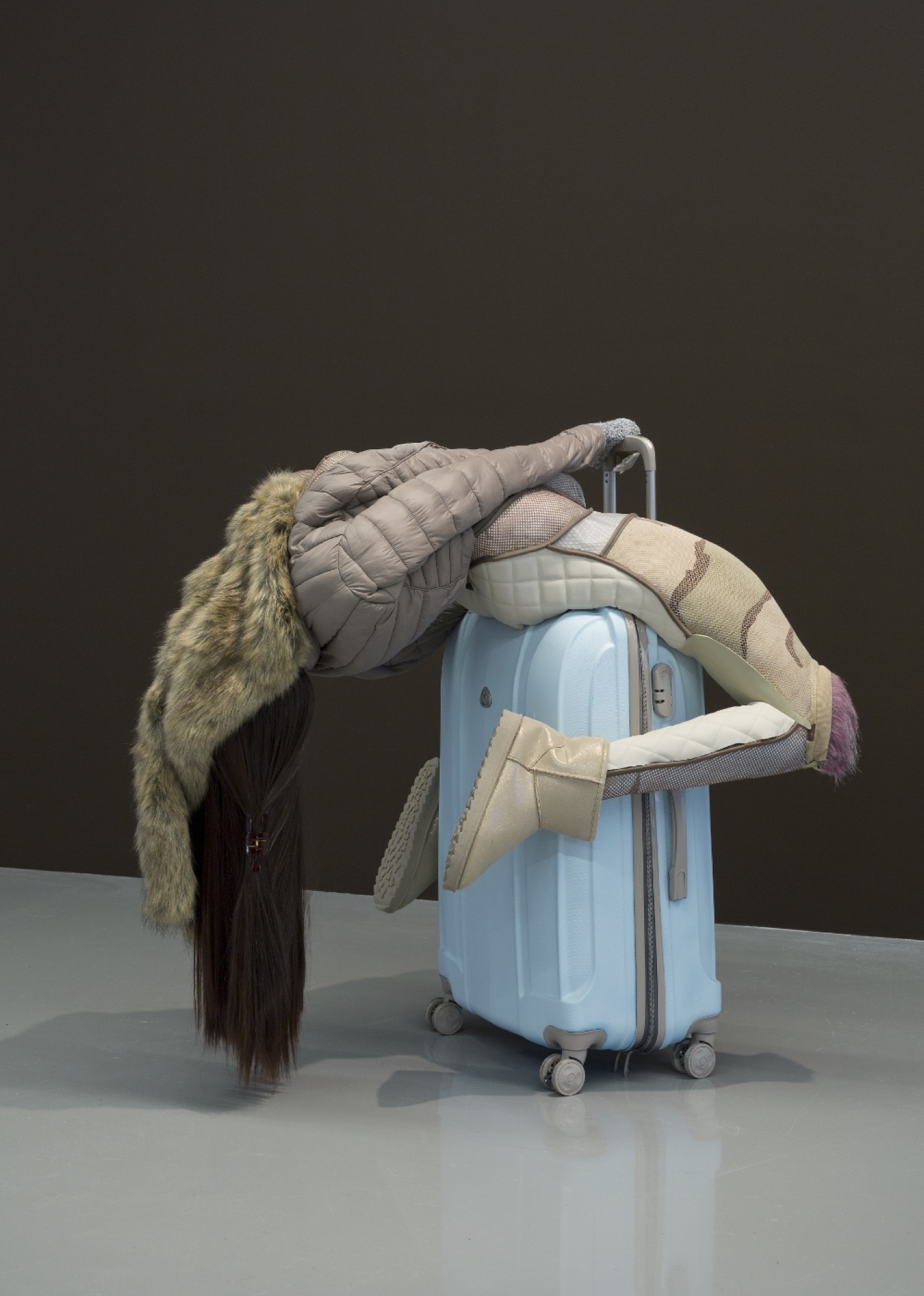

Two of the most visually striking works in the show—part of the genre of those works destined for media release—are Anna Uddenberg’s Savage #2 (Quilted Crutch) (2017) and Yngve Holen’s Hater Headlight (2015). Uddenberg’s sculpture of a woman entirely clad in synthetic material erotically astride a rolling suitcase comes close to a baroque examination of a ‘climactic moment’. This work refers back to a sculptural tradition concerned with weight, gravity, and its defiance, all the while appearing as a raunch-culture re-hash of Hans Bellmer’s disturbing 1936 series La Poupée. While the work might refer to excessive travel as a symptom of globalisation, it nevertheless has stronger connections to the past than the imagined future.

Yngve Holen’s Hater Headlight shines some bright scooter headlights through the gallery space. It hurts your eyes, and you are advised not to look at the light. While sight, light, technology and knowledge all share a high metaphorical status in western culture, this work avoids any reference to such lofty ideas. Instead, it seems a timely reminder that, perhaps moving into the future as well, there will always be some annoying person with their headlights on too bright.

Despite the visual impact of these works, the most pervasive work in the show is Damiano Bertoli’s L’Esprit Collective (2017). This work constitutes the exhibition design, the colouring of individual walls, and the inclusion of a simplified geometric column in each of the rooms. Indeed, a wall text at the entrance to the museum almost attributes the whole show to Bertoli. Bertoli has also designed plinths adorned with geometric grids for quite a few of the floor-based works in the show. Drawing from the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s, Bertoli’s intervention tries to re-imagine the museum according to colour scheme in a seemingly utopic and didactic gesture. As Bertoli’s work affects the entire show, the colours were chosen in consultation with the other artists. Yet these colours, the columns, the plinths and the grids, all lack internal variation, simply beginning and ending at the wall, ceiling or edge. Accordingly there is a tension between the space itself as neutral and invisible and the space as coloured and loaded. Perhaps it is the didactic promise that is withdrawn, perhaps it is the child-like colour scheme, but to me it comes across as some kind of neuronal remapping programme that ends as complex edutainment. A connection could be drawn between Bertoli’s use of colour and Marley Dawson’s reference point of Rudolf Steiner, who not only developed a biodynamic theory of soil but also an almost mystical theory of colour.

Fifty years ago, Michael Fried published his critique of minimalism in Art and Objecthood. This critique set up the terms of sculptural engagement as one between a hollow surface, the body of the viewer and the physical presence of the artwork. While some of these concerns can be read into Future Eaters as an exploration of sculptural tendencies, it is perhaps the slippages and absences between them that prove most insightful. Most of the works in the show do not draw specific responses from the bodies of the viewer, but nor do they suggest the compositional self-reflexivity that Art and Objecthood pitted against the minimalist tendencies. Of course, neither Fried nor minimalism should set the tone for today’s understanding of sculpture, but it is interesting to note the older, more transformative tradition of sculpture so present in these works. If this is the future of sculpture, then it looks a lot like a past even further back than 1967. The references to the history of sculpture feature so heavily in this exhibition that it falls short of the potential contained within such broad categories as the future, technology and indeed sculpture. Put simply, the curatorial premise writes cheques the work can’t cash.

David Wlazlo is a PhD Candidate in Art History and Theory at Monash University.

Title image: Future Eaters, MUMA, 2017.)