Frozen Blood; Frozen Blood; Frozen Blood

Victoria Perin

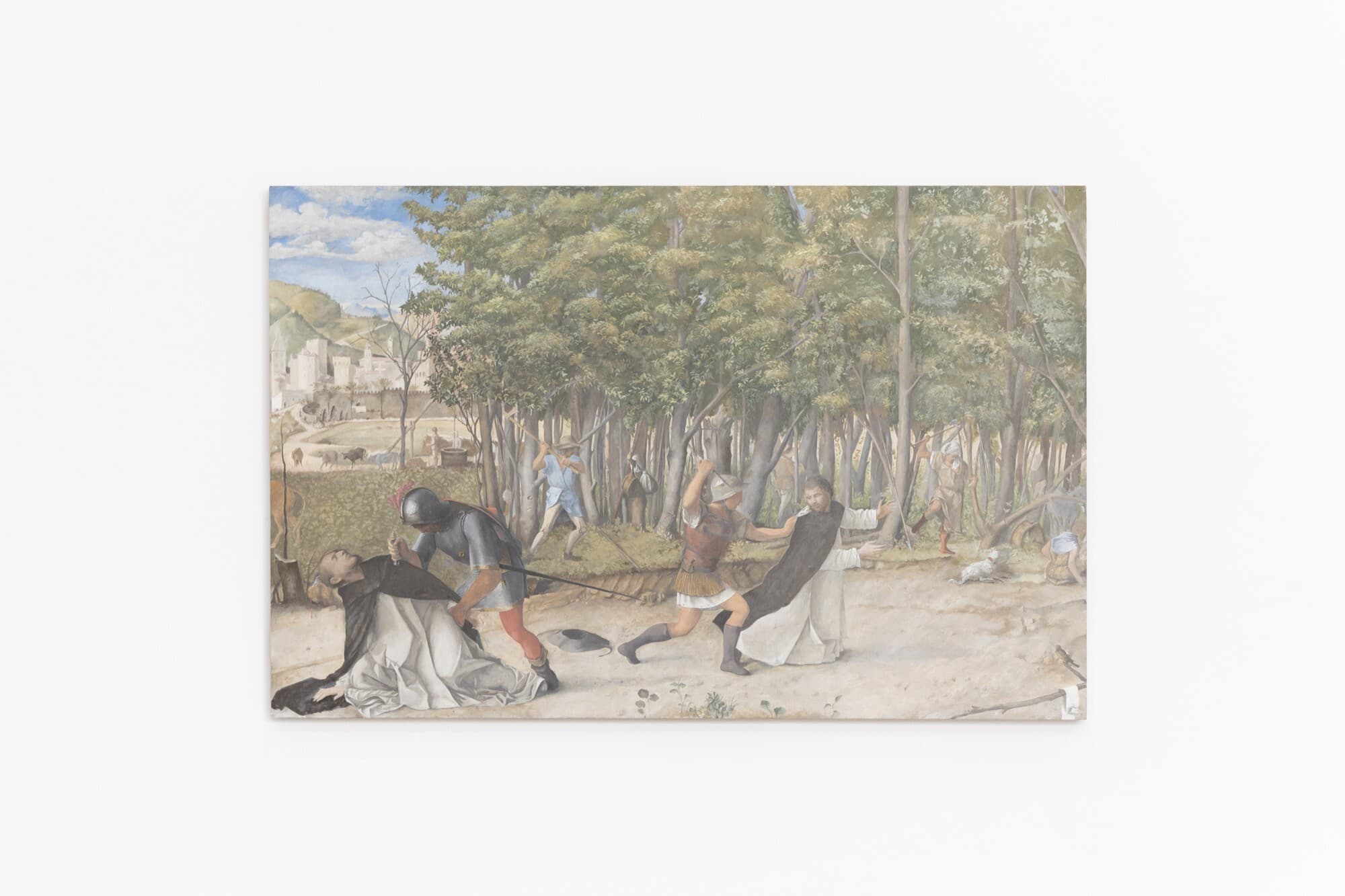

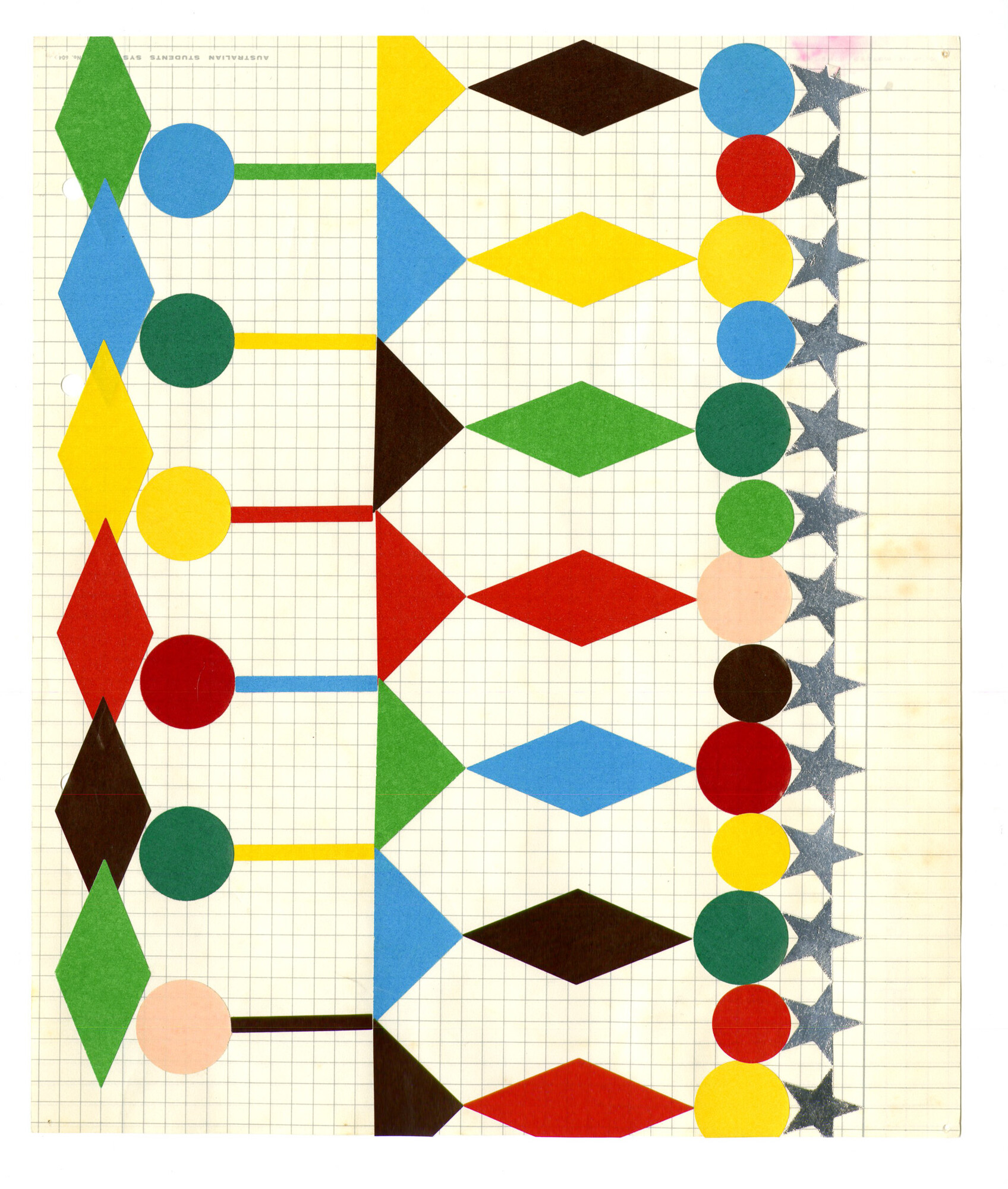

If Neon Parc had a mum and dad, it would be Vivienne Binns and Mike Brown. A dysfunctional couple, these two protagonists of Australian art lend the commercial gallery so much nourishment that Neon Parc’s Director Geoff Newton keeps curating them into exhibitions (despite the fact that he represents neither). Brown and Binns are difficult parents. Two very good artists with very healthy egos, Neon Parc is the byproduct of their brief affair in 1965. A child of divorce, then, the gallery has never quite matured emotionally, spiritually, and sexually—it looks to the past to explain the present. For me, this sentimental aspect of Neon Parc has always been its distinguishing feature.

In the group exhibitions that Newton curates, like Frozen Blood—currently spread across all three Neon Parc venues—you can see how his eye wanders to the art of the 1990s, 1980s, 1970s, going no further back than the 1960s. He doesn’t do this with any great conceptual rigour. Or, at least, none that he would articulate if you asked him. The exhibition text claims that Frozen Blood evokes themes of “immortality” as well as “time” in addition to “Bad Taste.” I get the feeling that Newton periodically drags the gallery back forty-plus years as a sort of personal return to the well. Throw the bucket down, pull up the cool, cleansing waters of Oz art history. It’s not a problem that it’s a little sexist and overwhelmingly Caucasian down there—that’s just part of the vintage charm!

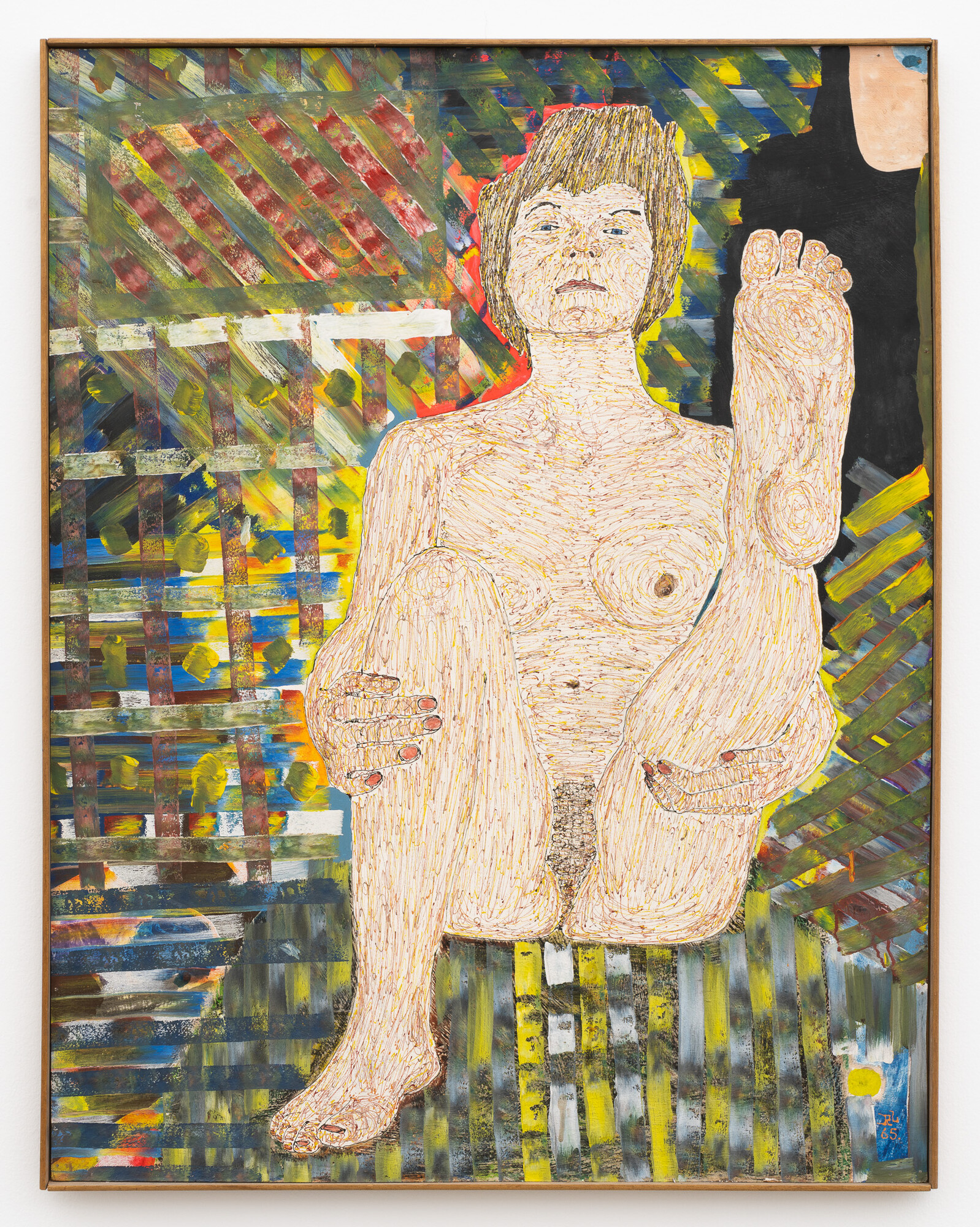

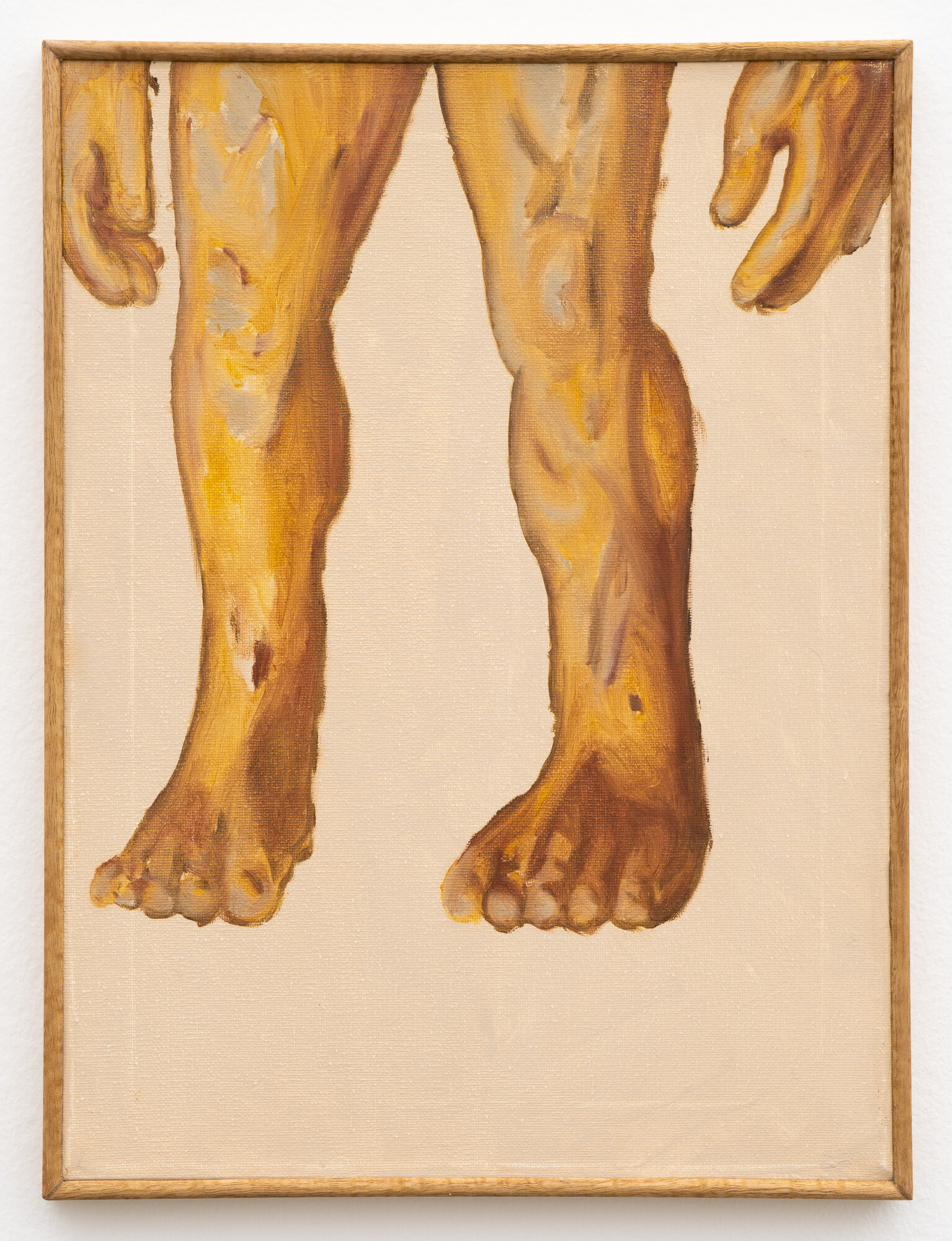

Forget what I said earlier: if Neon Parc had a mum and dad, it might actually be Pat and Richard Larter. The only artists that still make heterosexuality look fun, the Larters are both on display in the Brunswick edition of Frozen Blood. More icons of Australian art history, an English couple that immigrated to Sydney in 1962, the Larters were committed to sexual liberation, which was a core subject for their art. Pat posed for Richard’s paintings as an eternally manic nude. Her own art practice was more diverse, but Pat’s last great works featured male sex workers in the mid-1990s. In the past, only Richard was revered in the art world; today, only Pat is.

on board, 122.0 x 92.0 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Neon Parc.

I caught the curious scent of this overcorrection recently when speaking with a fantastic woman who gave off some second-wave vibes. She told me in no uncertain terms that Pat’s portraits and self-portraits were great, but Richard’s portraits of Pat were bad. Never mind that they share a fundamentally similar approach to their subjects. A popular interpretation today might stress that, while Pat could present her own image and sexualise the male form in her art, Richard’s depictions of Pat (and other women) are a problem. This flimsy application of the Male Gaze theory is in turn overcorrected in Frozen Blood, which has more than enough time for both the Larters, and little time for moral certainty.

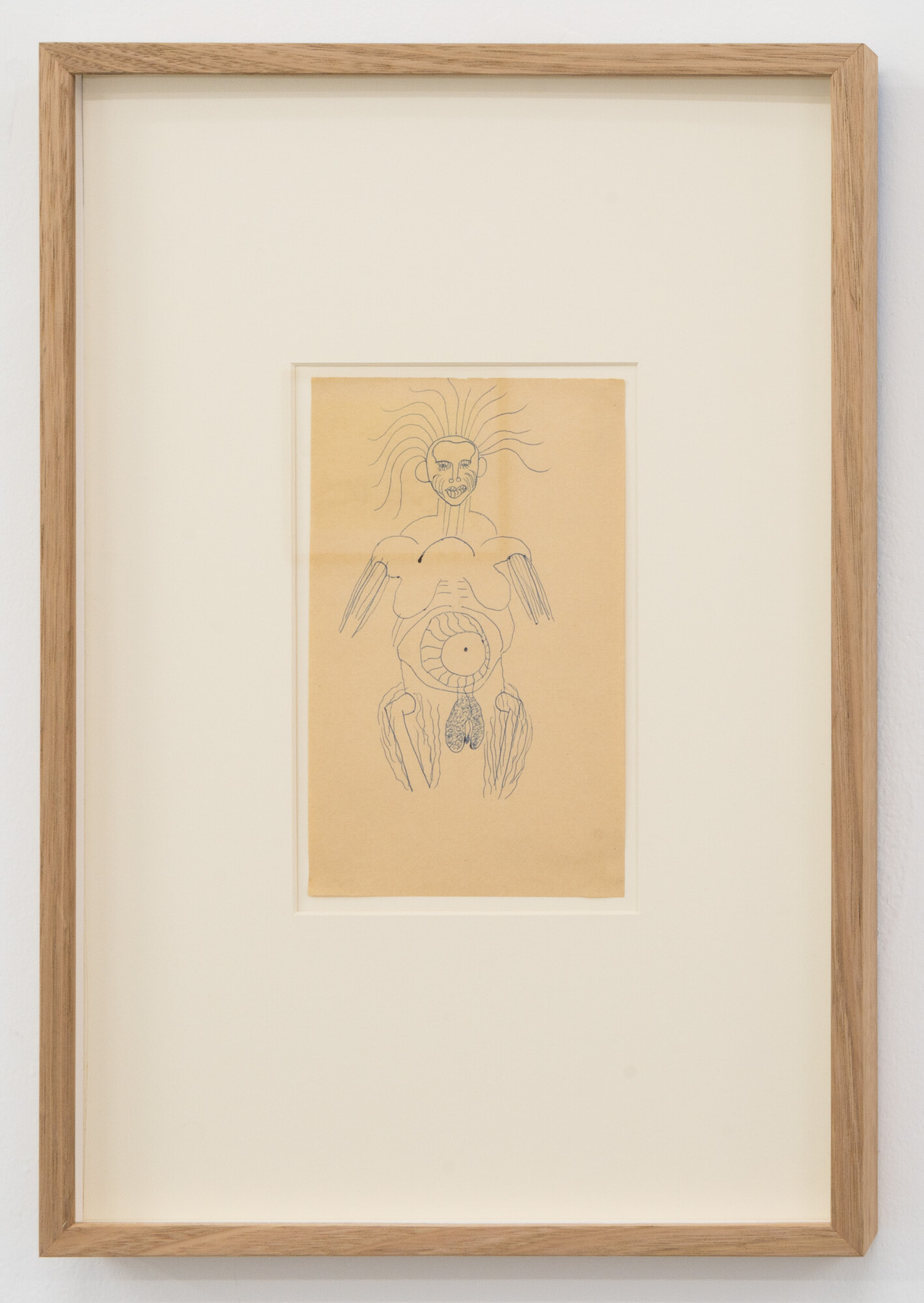

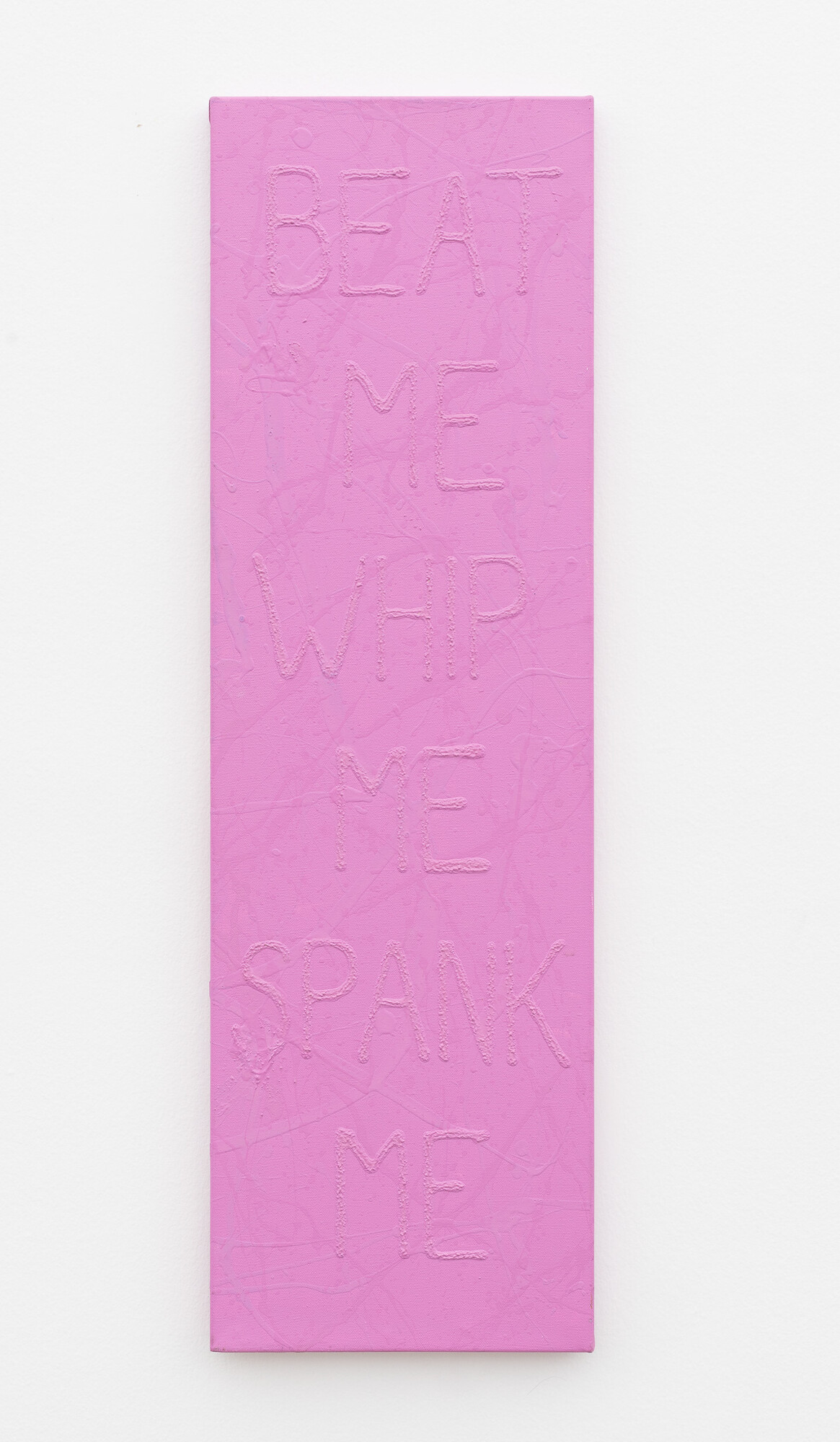

The historical counter-cultural victory of Brown and the Larters is used to parlay the exhibition into the porno outsider art of William Crawford in the 1990s (City and Brunswick gallery) and the hyper-sexed drawings of Rob McLeish (Brunswick). By calling Neon Parc the child of the Larters, that is to say, it struggles with its sexual identity. Like many children of the counterculture, it wants to be kinky, it yearns to transgress, but it is of course unavoidably straight.

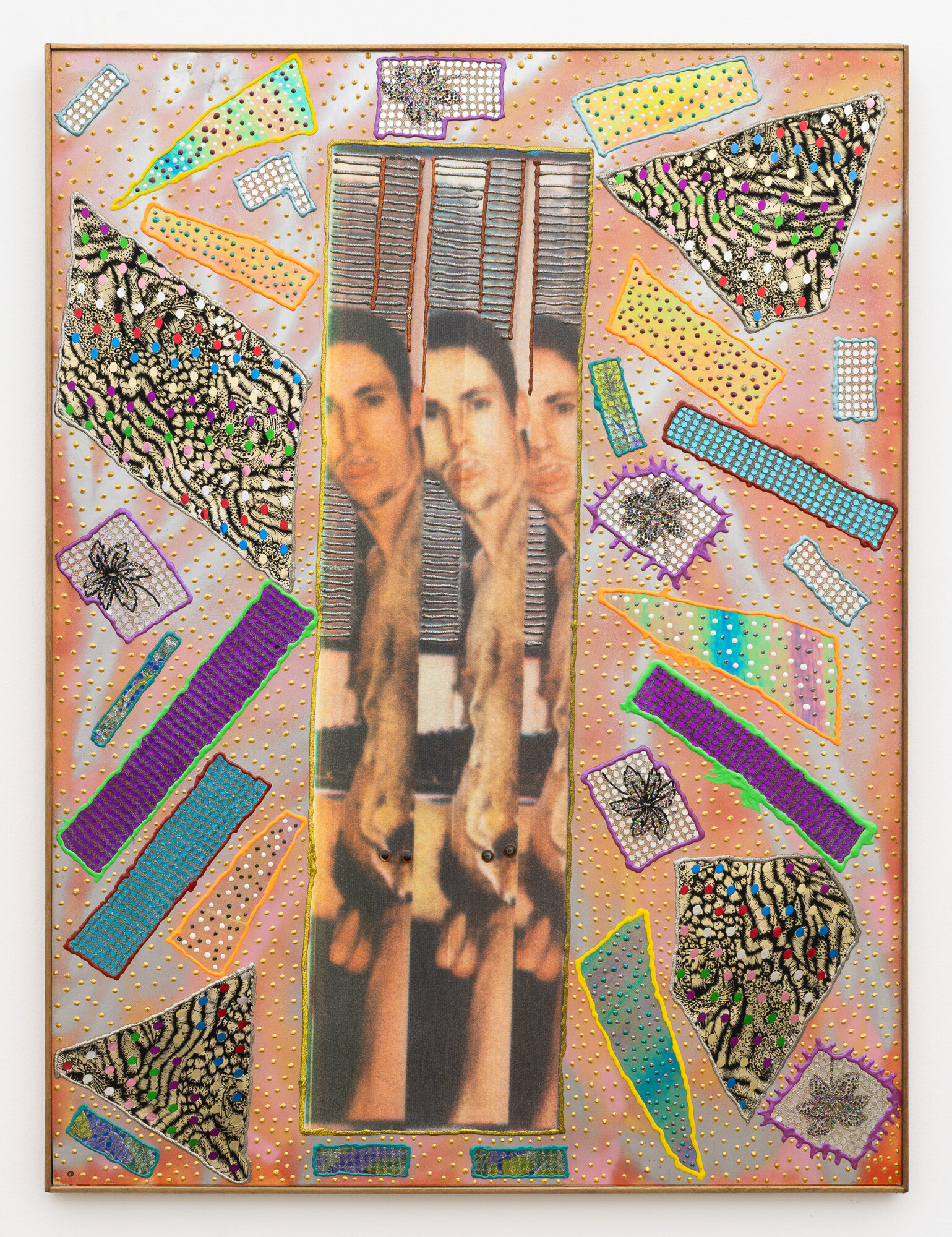

OK, fine. It’s obvious that if Neon Parc had a mum and dad, it would be Maria Kozic and Philip Brophy. They would both be aloof parents to the young Neon Parc, who would constantly act up for their attention. At the City gallery, Kozic’s paintings We Live (1993) depicts a glowing, white hand with freaky round pink nails. It’s dripping with lube and / or luminous, semi-translucent cum. Kozic has lived in New York for many years, and when Newton reintroduced the artist to Naarm / Melbourne with her recent work, I felt a gratitude I’ve rarely felt for a commercial gallerist. Kozic is the perfect Neon Parc artist; she’s emerged from all those historical surveys of feminist art with the twinkle of adolescence in her eye. She is a teenage boomer.

I feel like there is something that the exhibition description for Frozen Blood isn’t saying. It’s somewhat similar to the NGV’s current photography showcase Photography: Real and Imagined, curated by Susan Van Wyk, which greedily examines historical and contemporary photography as both documentary non-fiction and creative fiction (i.e., a juxtaposition of possibly everything). In the same broad way, Frozen Blood claims to probe “the link between artists who have produced abstraction and figuration.” (No more exhibition texts claiming to be about vaguely everything, please!)

As I roam from the City gallery to the Brunswick, then the new South Yarra location, I notice that the abstraction stays harmonious, but the figuration changes wildly. The unhinged figurative work that blossoms across the City and the Brunswick gallery is wrangled and tamed in South Yarra. The audience here will accept the cartoonish horniness of Brett Whiteley fucking a mistress doggy-style, but only cause it’s Brett. What is left over is a display that is more well-adjusted, and better behaved. In any case, for me, the beleaguered marriage between “abstraction and figuration” is apparent, but absolutely not what Frozen Blood is really about.

I was half right: Viv Binns is definitely Neon Parc’s mum, but my proposed dad is not the right branch off this family tree. Binns was Newton’s mentor in Canberra, where he went to art school. Everything clicks into place when someone reminds me that Peter Maloney was also teaching at the Canberra School of Art in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Maloney is an approachable hero to so many young artists from Canberra. His work always seemed very heart-broken to me, which was so much more interesting than being sexy or cool (which it also appeared to be). Maloney died in September this year, and he will be missed. His work is not in Frozen Blood, but I am told that Maloney introduced Newton to abstraction and the use of gay porn in fine art. Frozen Blood is about being a straight, white, Canberran teenager in the 1990s with a gay mum and a gay dad.

Frozen Blood is also an autobiography of Neon Parc, as it is currently being written. The City gallery, Neon Parc’s first space, opened in 2006 and will close permanently at the end of this exhibition in mid-December. Neon Parc’s new South Yarra gallery is a bold replacement. The City space was alchemical. It consistently flipped my perspective on art that seemed silly, slap-dash, and just all-around too minor, switching the context to make the same art appear precious, savvy, and lively.

Over its seventeen years, this intimate gallery has operated as a testing ground for many young artists, ushering their work into the art world beyond art school. I’m thinking of Spencer Lai, who made this progression quite literal in their recent solo exhibition, with a staged photograph of Lou Hubbard presiding over an art school tutorial. That exhibition was at the Brunswick gallery, but was following an inaugural solo at the City space in 2022. Frozen Blood features a great Peter Booth-esque, troll-core painting by Nunzio Madden, who was once Newton’s own student. Other exhibitors also wish to bear their local artistic lineage directly: Isabella Darcy shows a suite of non-paintings that are naked homages to John Nixon.

Can these same apprenticeships play out in the relatively grand Brunswick gallery, with its museum dimensions? This is to say nothing of the audience-shift that occurs when you take a grungy gallery out of the CBD and plant it off-Chapel Street. Fitted out so that it only slightly transcends the ambience of a garage, the new South Yarra gallery is giving literal kitchen sink realism. But that doesn’t disguise how this new showroom is directed at more upmarket patrons. Do the swank South Yarra clientele have any appetite to show-up for experimental sink-or-swim exhibitions? In any case, an alarming number of my peers have not yet made it out to the new space yet. That’s probably fine by Newton. It’s really not for them.

Frozen Blood provides a potent narrative for the closure of the City gallery. Neon Parc is changing and the vacuum it is leaving in the CBD will need to be filled by someone else, somewhere else. The children of Neon Parc have already been born, but whether they’ll ever be able to afford city rents is a different question. “You have to grow”, Newton tells me during one of my visits. When Neon Parc turns eighteen, it will have moved out of its childhood bedroom, with its nostalgia-fuelled erotics. Will trajectory from Brunswick to South Yarra mature the gallery beyond recognition? When the unassuming, important City space closes, will its loss have the effect of cutting off all the blood to the head?

Victoria Perin recently completed a PhD at the University of Melbourne.