From Impulse to Action; A Park is Not a Forest

Verónica Tello

Last week I was discussing “the canon” with my students. For them, the canon was a Western construct, which in Australia simply reflects the tastes and hierarchies of its settler society. My students were moved to raise a series of worthy questions: Do we seek to renovate the canon? Or do we instead opt out of it and locate different ways of appearing in, and making, art history? These questions struck me as having a renewed relevance in contemporary art discourse today. The weekend before my class I’d visited the newly established Bundanon Art Museum, located near the South Coast region of New South Wales (Wodi Wodi and Yuin Country). At the core of the Museum’s mission, and its inaugural exhibition, is a reckoning with Arthur Boyd, one of Australia’s most revered, and canonised, artists.

The Bundanon Art Museum is the latest development in the Bundanon Estate, gifted by Arthur Boyd and his partner Yvonne Boyd to the Federal Government in 1993. The Bundanon Estate comprises one thousand hectares of land near the Shoalhaven River (which influenced the artist’s famous and highly collected Shoalhaven paintings), and includes Arthur’s studio and the Boyd’s homestead Riversdale built in 1866. It also comprises a residency program for artists and writers (inaugurated in 1994, and in which I participated in 2015) and a museum, which houses Boyd’s collection. Predominantly funded by the Federal Government, the museum joins the small coterie of “National Collecting Institutions” alongside the National Gallery of Art, the National Portrait Gallery of Australia, the National Library of Australia and others. It is the only such institution located in regional Australia and one of two not located in Canberra/Ngunnawal country (the other being the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney/Gadigal country). As a National Collecting Institution, Bundanon’s Federal funding is part of a broader project to “preserve culturally significant buildings” and ensure “our national institutions continue to tell our national story”.

The Museum’s inaugural exhibition From Impulse to Action, curated by Sophie O’Brien, uses Boyd’s highly expressionistic ink drawings (circa 1960–1970), especially those he produced for the set design of Robert Helpmann’s Elektra ballet of 1963, as the basis for twelve commissions by contemporary artists. It initially struck me as odd to centre Boyd in this way. It seemed that Bundanon was using contemporary artists—and their nowness—to distract from the anachronism of building a new museum centred on Boyd. Upon seeing the exhibition, I was able to refashion my scepticism into a more generative question: What does From Impulse to Action tell us about the genealogies of Australian art that the Bundanon Art Museum, and the Bundanon Estate more broadly, cultivates?

Many of the commissioned works in the show pay homage to Boyd, offering a neat continuity between the modern and the contemporary, rather than making space for the generative differences (e.g., temporal, embodied, material). Jo Lloyd’s dance choreography and video installation, Death Role (2021), mimics the expressionistic forms and human/animal figures in Boyd’s drawing Double Figure with Shark Head and Horns (1962–1963) (used for the central set design for Elektra, and which Lloyd includes as part of her installation). Rochelle Haley, Sky Saxon and Vivian Cooper Smith, while creating distinct works, each centre Boyd’s vocabularies of modernist form, colour, tone and gesture, their discrete practices undeniably comfortable in Boyd’s palette. Tina Havelock Stevens’s sound and video installation, A burst of boiling rage (2021), shows the artist playing improvisational drums to the Elektra score. Installed next to two of Boyd’s drawings, and in the museum’s storeroom, the work is unsubtly co-opted into the museological framework to literally and metaphorically make a home for Boyd in contemporary art discourse.

Australian art history and criticism have indeed continued to make a comfortable home for modernists like Boyd. Indeed, in the last month alone MeMO review has published three reviews (including this one) that focus on the old boys. However, while some, like Rex Butler, have wondered about a new place for canonical artists like Sidney Nolan (by dubiously claiming him as “queer”), to my mind it seems more productive to name the canon’s exclusionary violence, and work to open up a space for different genealogies for contemporary art—ones which don’t simply re-inscribe the Euro-North American foundations of Australian art history.

There are ways of making art that have little to do with the figure of the white male genius that underpins the Western canon. Indeed, the most compelling works in From Impulse to Action have nothing to say about Boyd’s art historical legacy. Dean Cross’s 700 bowls and Uncle Steve Russell and Aunty Phyllis Stewart’s Fishtrap (both 2021) speak of the refusal of First Nations knowledge to be reified by the museological canon (the empty shelves of 700 bowls signifies this). Such knowledge nonetheless manifests instead through intergenerational and collective care. Workshops run by local Gadhungal Murring Elders Uncle Steve and Aunty Phyllis shared knowledge to create a nawi (canoe, for Fishtrap) as well as woven bowls for Cross’s installation.

Emily Parsons-Lord’s Every essence of your beloved one is captured forever (2021) tests from a settler-colonial position whether carbon, and Country, can be a container for memory and history. Parsons-Lord’s work takes as its starting point both the artist’s memories of visiting Bundanon as a kid with her late mum, and Bundanon’s geological history. Her video presents footage of the museum’s surrounding landscape and documentation of a dry-ice sculpture transitioning from solid to gaseous form. On the floor of the museum, she lays down the remains of the sculpture, charcoal from local bush-effected trees, and a diamond generated from the ashes of Lord-Parson’s mum, using a technique that accelerates the geological forms and heat usually required for such a process (and which would normally take over one billion years).

The vitality of the works by Cross, Parsons-Lord, Uncle Steve and Aunty Phyllis derives from their attention to the demands of the contemporary, not least of which are a settler-induced climate crisis and moves to both indigenise and demonumentalise museums. It is, of course, the enduring presence of the canonical Boyd that legitimates Bundanon, and has made possible its long-standing contributions (through commissions and residencies) to contemporary art practice and discourse. The paradox of From Impulse to Action is that it is most compelling when its artists break most radically from the exhibition brief, and from the historical model that Boyd represents.

This paradox is what makes Bundanon an interesting, if not also potentially fraught, institution. As the inaugural show demonstrates, at the core of the Museum’s purpose is to sustain Boyd’s legacy. This distinguishes Bundanon Art Museum from say the Museum of Contemporary Art or the Art Gallery of NSW, since it is thereby committed to an art historical narrative in which (at least rhetorically) all roads lead from Boyd. While I welcome the addition of a museum that supports contemporary artists, at the core of contemporary art’s critical contemporaneity (especially in Australia) must surely be a confrontation with settler-colonial history. Insofar as the show aims to (re)lionise Boyd (a la Butler on Nolan), it fails this test. An interesting contrast to this is the Powerhouse’s Eucalyptusdom exhibition, which Nick Croggon argued succeeds. However, could Bundanon (given its foundations) have done anything different? And given its vast amounts of government funding, this outcome seems quite deliberate—and part of a broader cultural project that is about folding potentially errant artistic practices back into a public national identity.

The canonising, national building impulse underpins many of Australia’s art institutions. Yet the tension between this and contemporary art’s multiplicity can be a dynamic space from where new genealogies of art in Australia are constructed. These genealogies are often born out of minor histories, archives and memories that are salvaged and cared for by artists, curators and writers who don’t feel at home in Australian art institutions. Salote Tawale’s curated exhibition A Park is Not a Forest, showing at the Sydney College of the Arts Gallery, gives us a strong sense of how it’s possible to cultivate alternative infrastructures and futures for art in Australia.

When I first visited A Park is Not a Forest Tawale happened to be there. Tawale, who is a close friend, is also one of my collaborators on a research project focussed on the limits and possibilities of structural change in Australian art museums, with a focus on regional art spaces. I don’t have critical distance from my subject. I care about the state of Australian art institutions, and Tawale does too. This shared care binds us. It also binds Tawale and the artists in A park is not a forest. They are friends with Tawale, many are friends with each other (and some are friends with me too, namely Claudia Nicholson and James Nguyen). It’s through friendship that many of us find the often otherwise elusive support to forge the genealogies we desire.

A Park is Not a Forest brings together a group of artists—Marikit Santiago, Sione Tuívailala Monū, Claudia Nicholson, James Nguyen and Tiyan Baker—who Tawale describes as working through their “inherited colonial histories”. Tawale, who is also an artist, takes no curatorial distance and includes herself in the show. The colonial histories inherited by these artists are those of the British Empire in Borneo, Australia and Fiji, the Spanish Empire in Latin America, and US imperialism in Latin America and Vietnam. The artists are part of different diasporas—their commonality is that they live in Australia as settler-colonists of colour grappling with their inheritance. As the Chicana writer Gloria Anzaldúa might say, as diasporic subjects the exhibiting artists “take inventory” of what they’ve acquired or that which has been imposed on them. They sieve, to winnow out the lies, and map the ways in which their inheritance shapes them. Each artist does this in distinct and compelling ways, mostly using autobiography/self-portraiture and personal/family archives to make themselves appear on their own terms within the white cube. However, James Nguyen takes a different approach: we don’t see him, or his heritage, on display but rather the canon of Anglo-Australian arts.

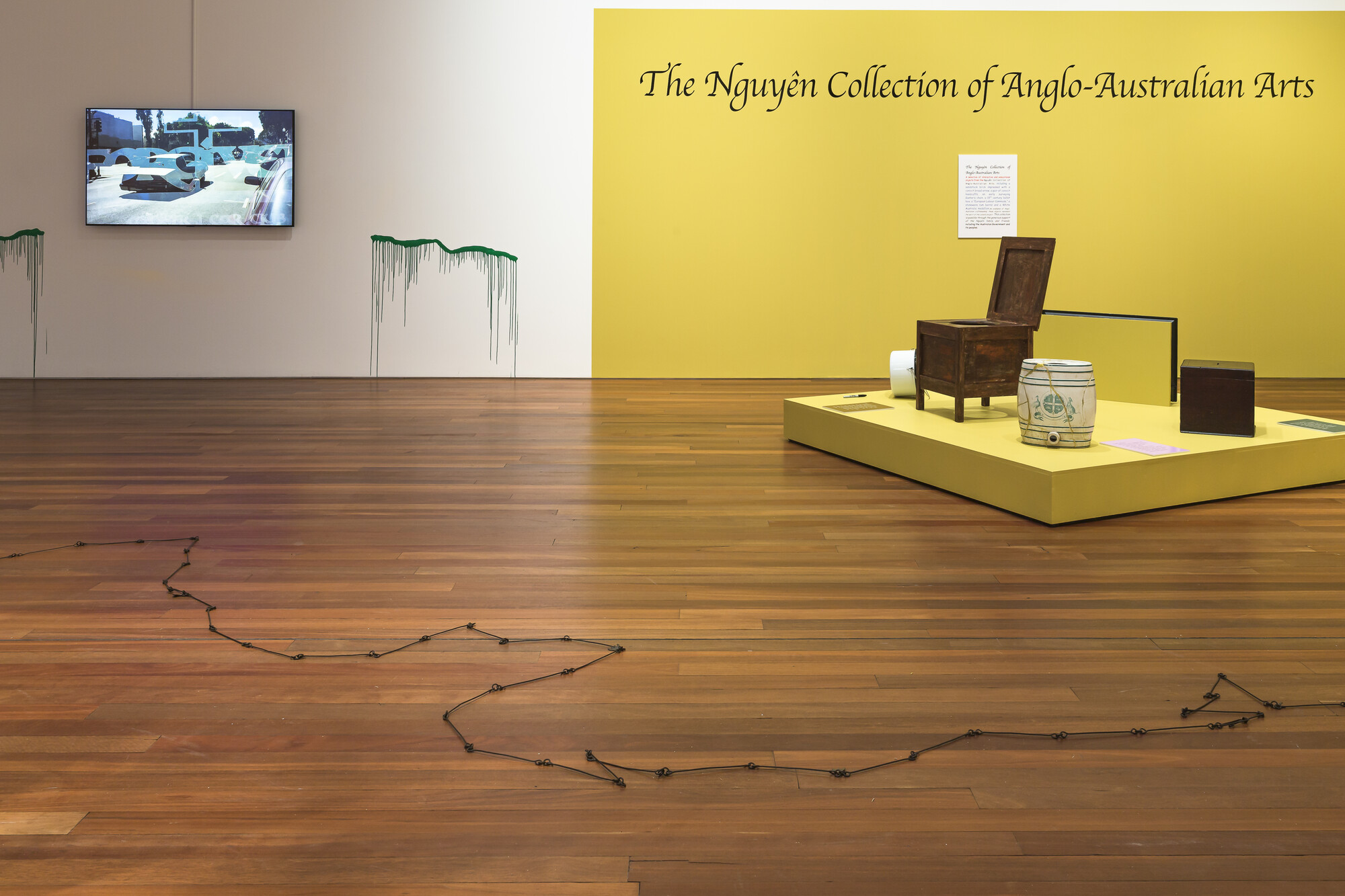

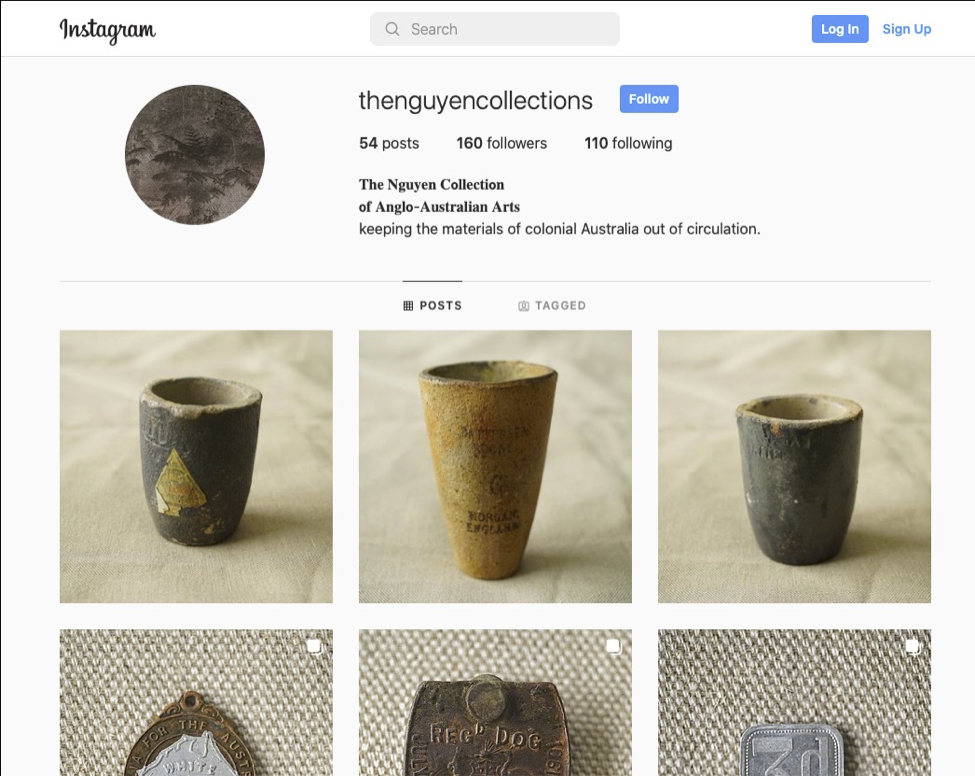

A Park is Not a Forest offers the inaugural showing of James Nguyen’s The Nguyễn Collection of Anglo-Australian Arts (2021-), a work of institutional critique which to date has only existed as an Instagram account. The Nguyen collection began in 2021 and seeks to keep “out of circulation” Australian colonial objects, often of museum quality, which Nguyen purchases at auctions. To date, the collection comprises over fifty objects, including nineteenth century gold pans, coins and jewellery, early twentieth century police batons and handcuffs, and an invitation to the 1901 opening of Parliament House. Nguyen’s installation The Nguyễn Collection of Anglo-Australian Arts (2022) displays an enamel (shit)bucket, prison handcuffs, a White Australia medallion and a Gunter’s chain, a seventeenth century Anglo-invention used to measure distances when surveying land. Through signage, authored by Nguyen and printed in Comic Sans font, the installation encourages audiences to interact with the display, prompting us to take selfies with the White Australia medallion, or to sign the shit-bucket and become a co-author to “ready-made racism” (after Duchamp). Nguyen suggests that everyone is an author of Australia’s histories and elicits in us the agency to map which histories pass through us. The aim is to denaturalise the idea that we all have a shared origin story or that this story is felt in similar ways amongst unevenly supported and included communities within Australian art institutions.

Throughout the exhibition space, Tawale has splattered green paint on the walls, treating the entire white cube as an installation space to be disrupted—not unlike how Brook Andrew treated the museum walls when he curated NIRIN (Biennale of Sydney, 2020). The green drips allude to the concept behind the exhibition title. While parks are manicured controlled spaces (like the English garden at the Boyd’s homestead), spaces without human intervention see climbing vines and wild grasses freely rise. For Tawale, even if we are living in a colonial landscape, wild histories and ways of being can still manifest.

The question remains: which structures will support such wildness? Probably not colonial institutions which love modernism rebooted, but structures which can grapple with their colonial foundations in ways that make space for genealogies that diverge from the Anglo-Australian canon—and yes, they might get wild (as in A Park is Not a Forest or Eucalyptusdom). If I was still in the classroom with my students, I might tell them to hedge their bets on friendship as a key support structure to locate enduring ways of coming together otherwise at the borders of the canon.

Verónica Tello is Senior Lecturer, Contemporary Art History and Theory, UNSW Art & Design, Sydney.