Fiona Foley: Who are these strangers and where are they going?

Maddee Clark

The Ballarat International Foto Biennale launches with a performance of the title work of Fiona Foley’s headlining major solo exhibition, Who are these strangers and where are they going? The song is performed in both Badtjala and English by a group of young local Aboriginal singers. The title work of the show, a new commission, is a soundscape utilising an old Badtjala song made in collaboration with Murri musician Teila Watson. It is accompanied by an installation of 3000 oyster shells and sand, which greets audiences as they enter. The song records the Badtjala peoples of K’Gari’s first sighting of the Endeavour, which as Foley notes in her doctoral thesis, was observed and tracked extensively by Aboriginal peoples of the east coast as Captain Cook proceeded in his project of naming and claiming sites along it. TakkyWooroo, named by Cook as ‘Indian Head’, is integral to the work as the site where looks are exchanged.

The European gaze, pre-determined as it is by discourses of colonialism, slavery and racial science, conceptualized the Aboriginal people of K’Gari as an inferior race before ever encountering them. The song recalls another gaze, that of the K’Gari traditional owners, documenting and recording their observations for the generations to come. It disrupts the white historical memory of first contact by asserting that, as Aileen Moreton-Robinson has said, Aboriginal people are indeed deeply knowledgeable about whites, their movements, and their intentions.

The performance finishes, the audience applauds, and the space is momentarily filled with the sound of Aboriginal children and their families laughing, eating and talking. Some of the children walk up and touch the installation of oyster shells and sand with their hands. The drier business of the Biennale launch continues, somewhat deterred by their presence. The soundscape expands and fills the room. I can smell the salt air. I want to take my shoes off.

Coming back to view the show in daylight, I watch Biennale punters hurry in and out of a series of small alcoves surrounding the installation, in which three of Foley’s major photographic works from the last thirty years of her practice are positioned. The Biennale seems disorganized; there is no wall text and the catalogue is hard to find, leaving the audience with little information about the works to go on. This, to me, seems to demonstrate either a lack of care on the part of the Biennale towards Foley’s show, or a commitment to maintaining an air of mystery about the works.

The gathering of these works together in one place reflects the deep complexity of Foley’s thinking. In the context of the Foto Biennale, it also shows her intimate focus on photography as a colonial medium, most exemplified by her habit of positioning of herself in the frame, looking back. The work Batdjala Woman (1994), for example, is inside a canvas tent in the centre of the mining exchange and is visible only by kneeling or leaning down and peering through a sheer canvas as the soundscape plays around you. The tent itself is a secretive object, weighed down with a series of ropes tied to heavy stones placed around it on the gallery floor; ropes which look identical to the ones binding the hands of the Aboriginal subject of the Oyster Fisherman (2010) who swings, tormented, from a tree. By the time you reach the tent, you have come far enough into the mining exchange building that the Oyster Fisherman, HHH (Hedonistic Honky Haters) (2004) series, and the Wild Times Call (2002) works have had a chance to stare out at you.

Foley’s approach to white supremacist historical representations, I realise, is more than a practice of subtlety, seduction and smuggling, it is guerrilla warfare. She deploys a set of conscious, strategic actions required to publicly speak the things in history that are shrouded in unspeakability. Speaking at the artists’ talk, she describes creating the public work Witnessing to Silence in 2004, which is installed outside the Brisbane Magistrates’ Court as a practice of ‘public art by stealth’. The work speaks to Queensland’s hidden history of massacres and warfare against Aboriginal people, but Foley had initially pitched the work as a reflection of extreme weather patterns. She recounts then explaining it while it was in process as a representation of traditional Bora grounds while it was being installed, only to publicly reveal its meaning months after the work had been installed permanently.

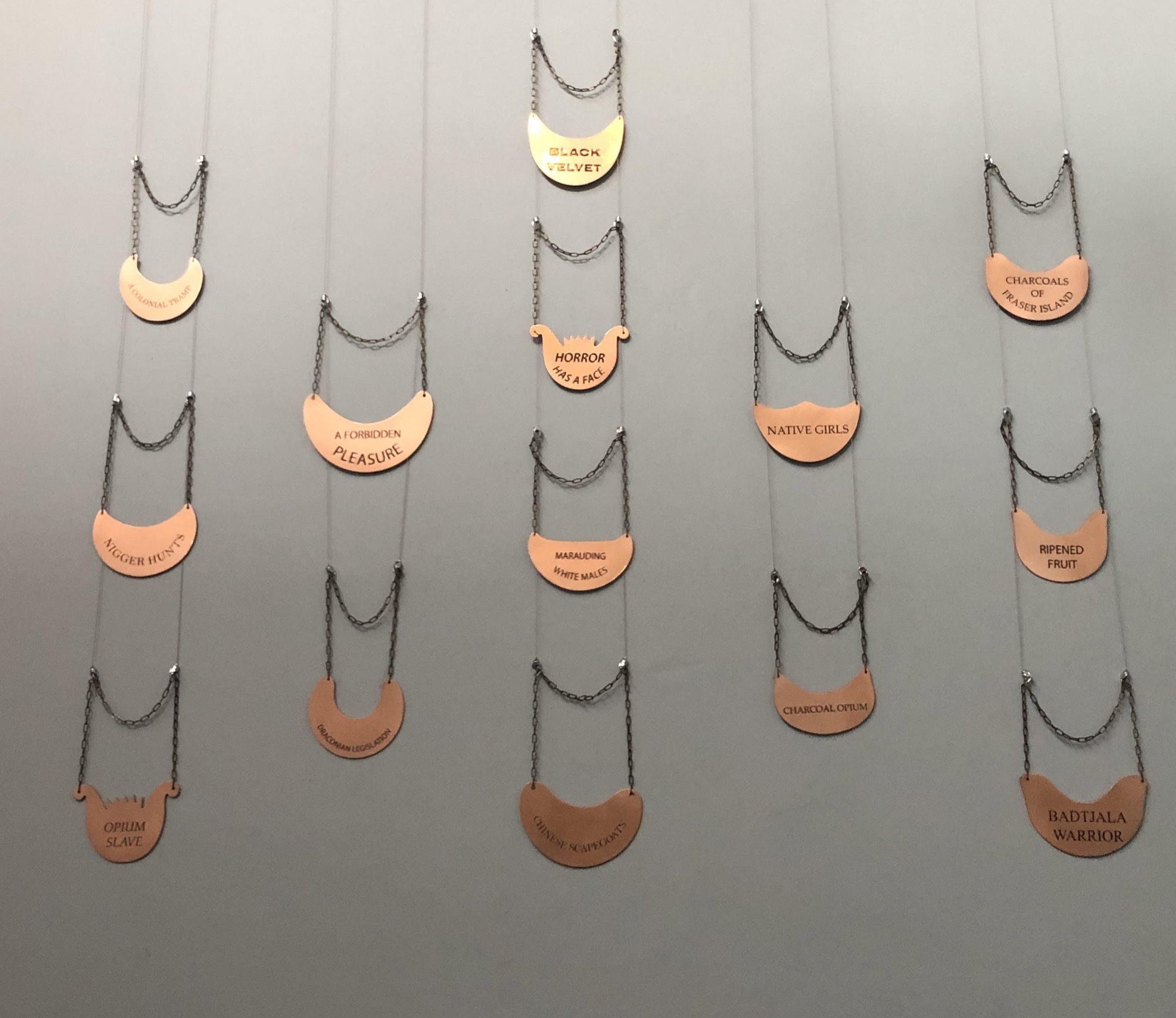

A second room in the Mining Exchange contains a selection of Foley’s other works relating to the Aborigines Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act of 1897. A video work Bliss (2008), the photographic series Let A Hundred Flowers Bloom (2010) and Horror Has a Face (2016) confront the complex intertwining of the opium industry and colonial power in the twentieth century in Queensland, a history that, as she notes, has been almost erased entirely from national consciousness.

During the late 1800s and well into the 1900s, protection acts in most Australian states were legislated to govern and control the lives of Aboriginal people, to criminalise and displace, to remove children, and to separate families. Though each of the state-based protection acts had implications for the criminalization of alcohol consumption by Aboriginal people, the Queensland Aborigines Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act (1897) is set apart from other state legislations of the Protection era by its focus on opium, the legal consumption of which had been used until that time to generate profit for the state. After being smoked, opium ashes were used as a form of payment for Aboriginal indentured labour. In the 1970s, Lakota professor Beatrice Medicine wrote on the colonial utility of alcohol and legislation relating to addiction. Drugs of addiction, she writes, are used by invaders firstly as a means of dispossession, to coerce Aboriginal people into giving up land and labour to the invaders. Then, they are utilized as a means of regulation and criminalization to further disperse and incarcerate Aboriginal populations through discourses of addiction and immorality.

Fiona Foley similarly describes the uses of opium legislation in Queensland as a ‘Trojan Horse’. Horror Has a Face shows not only the opium smoke, the pipes and the hedonism of the opium den (the works are surrounded by soft couches, peacock feathers, and thick rugs that carpet the floor); but it also captures the glinting faces and bared teeth of the slave masters, the bald evil of indentured servitude and those who benefited.

Archibald Meston was appointed to the position of the Protector of Aborigines in Queensland from 1897-1902 and was the major architect of the Act. He is recorded as an eccentric ‘showman’ and was a killer of Aboriginal people on the frontier turned ethnographer with an interest in studying Aboriginal people. In Staged savagery: Archibald Meston and his Indigenous exhibits (2016), Judith McKay and Paul Memmott wrote of Meston that he was known to deliver public lectures on Aboriginal ethnology on a stage surrounded with live animals, artefacts and live Aboriginal people, “elaborately ‘made up’ with paint, feathers, etc. and bearing weapons to emphasise their savagery”. Prior to his appointment as protector, he was also the director of a perverse stage production, The Wild Australia Show, which was intended to tour Australia and then the world as an exhibit of Aboriginal savagery and exoticism. Thirty Aboriginal men were ‘recruited’ for the show, before being abandoned by Meston in Victoria when the show failed financially. The subjects of Foley’s photographs are very still, rigidly posed. That Meston, who occupied K’Gari for a period of time in the late 1800s, could occupy the roles of killer, exhibitor and, eventually, protector of Aboriginal people illuminates the dystopian horror of the 1897 Act. I look for Meston in Foley’s photographic works, see him in the field of swaying poppies in Let A Hundred Flowers Bloom. I look for him in the faces of the white men posing in Horror Has Face, staring wide eyed and vacant into the camera. I wonder if he is the man holding the whip, the gun, or the conductor’s baton.