Sound (in my car)

I listen to a podcast, The Huberman Lab, as I drive to the Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP). Psychiatrist Dr Anna Lembke warns the host, Andrew Huberman, that we are experiencing the most boring time in the history of humanity. Despite enormous inequality, Lembke notes that most people can satisfy all their physical needs without ever leaving home. It makes the pace of life both predictable and paradoxically hard to deal with. The irony resonates with me as I arrive to view Fertile Ground, an exhibition exploring food as an index for the complex social, historical and personal politics at the heart of globalisation. Curated by Sarah Bond and Olivia Poloni, it features works by nine artists from Australia and Southeast Asia.

Touch (in the gallery)

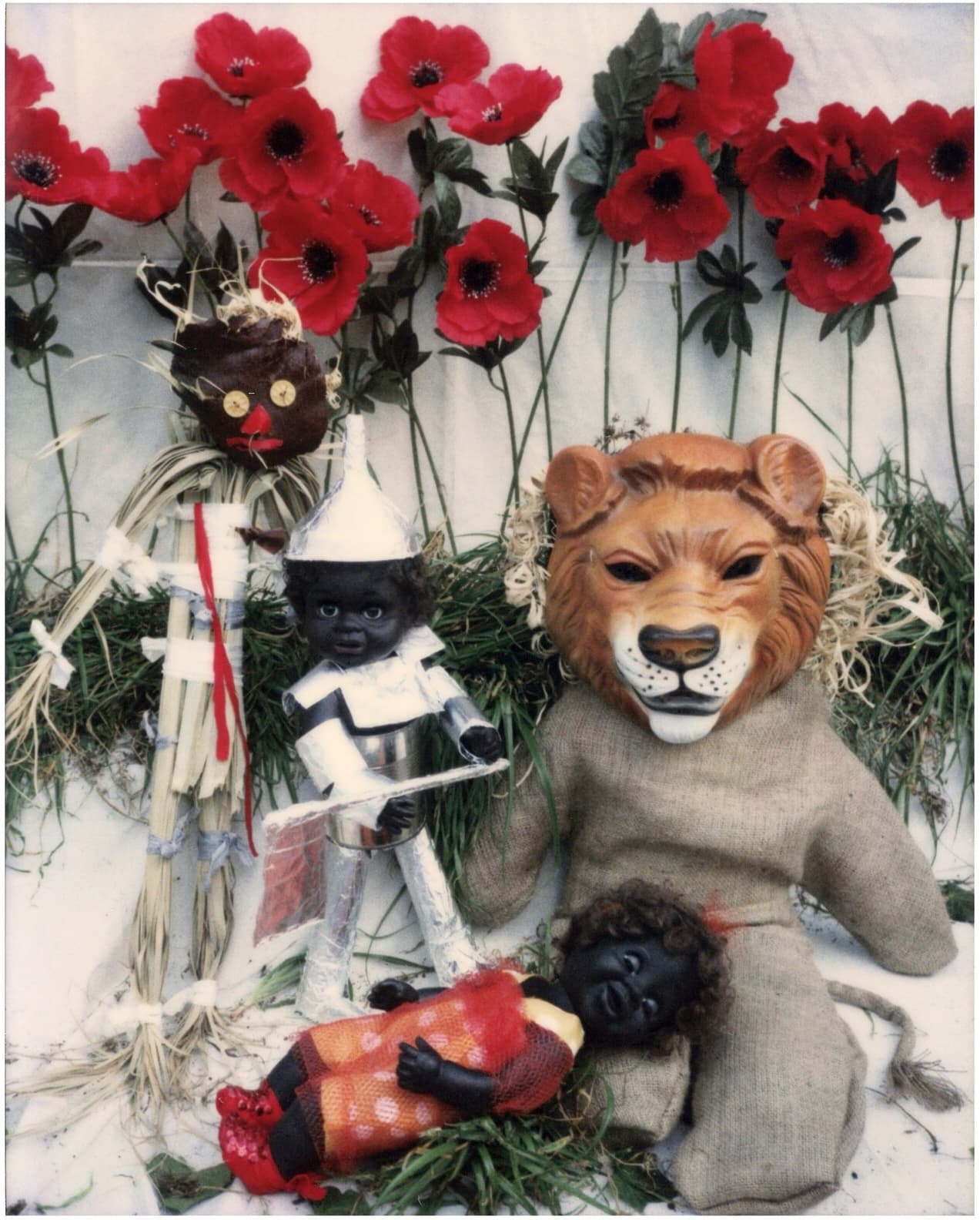

The first work is The Spade (2020), a video from the Field Work project by Thai-born Australian artist Kawita Vatanajyankur. In it, the artist is depicted harnessed to a structure. She dives into a bright-yellow pool filled with soil, which she digs at with her bare hands. I reconsider the consequences of boredom. The monotony in the movement of this performance dehumanises the artist’s body while addressing me with other questions: Do we still need anthropomorphic images of labour to understand its implications? Do we only give things our consideration when we recognise in them a resemblance of ourselves? I read that Vatanajyankur is interested in the human labour behind fast fashion, human trafficking, fishing and agriculture. Humanity’s egocentric appetite for self-identification has provoked food crises—she thinks about labour; I think about labour and the climate too.

I turn left. Mounted on the wall is Sunset (2019), a photographic series by Cambodian artist Kim Hak. Five large-scale prints show accumulations of fallen leaves and fruits: azadirachta indica, cashew, papaya, rose apple and citrus sinensis—green sweet orange. The works are inspired by a conversation the artist had with his parents about the ineluctability of death. Organic materials are photographed decomposing into the ground, epitomising the cyclic nature of life and death. The images take me to Greece and the myth of Demetra, the goddess of agriculture who lost her daughter to the god of the underworld. In her despair and later joy (following their reconciliation), Demetra gave birth to the four seasons. The seed remains after death and is also the door to a new life. It operates in a recurring journey that goes from morbidity to hope, and from tree to soil. “In a handful of healthy soil there are more organisms than the number of people who have ever lived on planet Earth”—the words of Dr Kristine Nichols, who is a leader in the movement to regenerate soils, resonate here. By overexploiting the land, we have affected the circularity of Demetra’s seasons. The poetry of Hak’s work reminds us of the importance—and inescapability—of their return.

On the opposite side of the room sits Chhaapaa (2019), a photographic series by Fijian/Indian artist Shivanjani Lal, who lives between Australia and the UK. Lal presents glimpses of her family’s sugar-cane farm in Fiji through sixteen Polaroids stretched onto paper, brown like sugar. In a video on the CCP website, the artist warns that the farm should, in fact, be called a plantation, a term that connotes European colonialism. Intrinsic to the Polaroid is its nostalgic quality—but where do we draw the line between romantic nostalgia and the preservation of memory? Alongside memory, the work speaks to affect. There are familial ties (what we see are intimate spaces), intergenerational connections (through family portraits), and geopolitical affairs (Australia surfaces on a globe, the Polaroids are captured in Fiji and the prints are made in India). Food is stored within an archive.

Sight (in my homeland)

In the Gallery of Modern Art Empedocle Restivo in Sicily, there is a painting by Francesco Lojacono, Veduta di Palermo (View of Palermo), an example of Romantic Realism, dated 1875. Of the many plants and trees depicted in the work, none are indigenous. Olive trees originated in Asia and were introduced through the Greek diaspora; the aspen tree is from the Middle East; agave from Central America; eucalyptus from Australia; prickly pears from Mexico; loquat from China; and even the citrus tree, emblem of the island, came from India with the Arab peoples as they drifted from North Africa. You can imagine the artist creating his Veduta. He is sitting still, somewhere in the street of Santa Maria di Gesù, romantically observing and realistically documenting the botanical species of the Conca d’Oro plane. Francesco was also a man of action. Fifteen years earlier, in 1860, he had enrolled as a volunteer in Giuseppe Garibaldi’s Expedition of the Thousand, which promised to liberate Sicily from the foreign monarchy and unify Italy. His representation of the botanical, and so cultural, diversity of the island is in tension with his desire for freedom; the hybridity that distinguishes Sicily came with the visits of welcomed guests as much as occupiers.

Taste (from the gallery to my kitchen)

I continue walking through CCP’s maze of food, encountering Keg de Souza’s the earth affords them no food at all … (2017), a title drawing from a 1697 quote by English coloniser William Dampier. The work encompasses six vacuum-sealed storage bags filled with food dating from pre-colonial to contemporary times. This arrangement simulates the geological stratification of the soil that starts with seeds, dried fruits and weeds, passing through exclusively Australian processed food—such as sugar candies and chocolate cakes—and ends with nutrient supplements in capsules. Yet de Souza’s piece is not an object. The impact of her practice shines in relation to larger installations that she names “radical spaces” and that I experienced elsewhere. The most recent case was Not a Drop to Drink (2021), a performative dinner that took place last May at Arts House, Melbourne, to address water and food shortage and—quoting de Souza—“prepare communities for climate crisis”. The artist relies on architecture, interdisciplinary research and mapping to create these sites and initiate real-life conversations around themes that span decolonisation to environmental activism, with food often operating as a key index. Both methodology and matter, food is viewed through the ordeals of history and employed as a social tool to bond with in a convivial format.

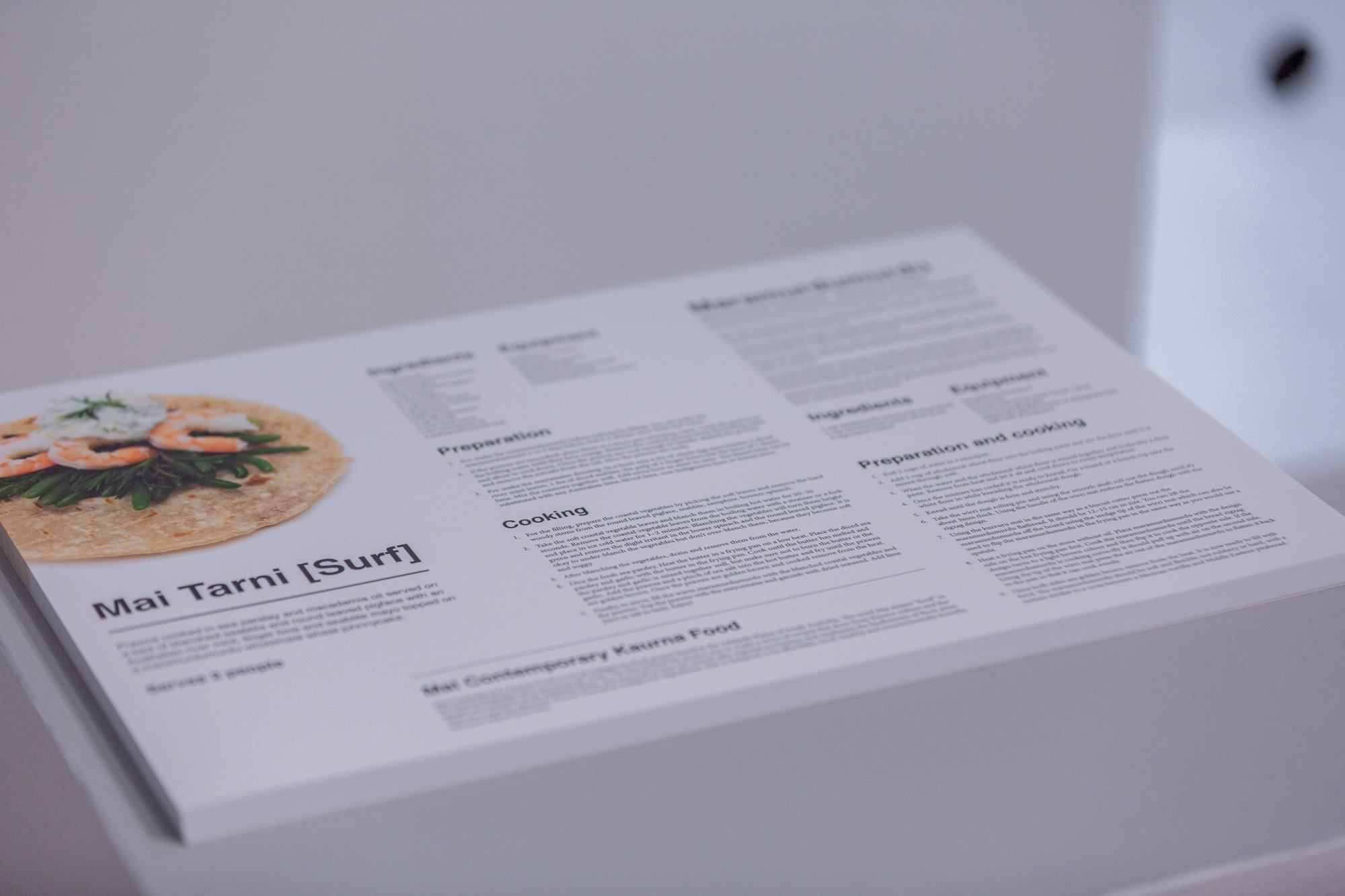

Next to de Souza’s piece there are two plinths offering recipes. The work is by artist James Tylor, who is of Nunga (Kaurna), Māori (Te Arawa) and European ancestry. They are called Mai Tarnta Wama (Southern Plains) and Mai Tarni (Surf): selections from Tylor’s Mai Contemporary Kaurna Food project that proposes dishes drawing from Indigenous traditions with a contemporary twist. I pick them up with the intention to try one at home, but I realise that they are based on meat and fish, which I do not eat. Am I allowed to reinvent them?

While I consider this question—the answer might find me in the kitchen—I walk into the next room. I am called in by the music coming from a six-screen, twelve-speaker installation by Thai artist Arnont Nongya. I have now entered a market where I can see animals, vendors and buyers, and hear their voices overlapping, conflating into one. The title of the work, Opera of Kard (Market) (2019), suggests a staged drama (in the gallery, speakers and cables are exposed, and the boom is visible in the videos) arranged to music in its totality. The word “opera” next to “market” figuratively elevates the subject from popular to elite. The location is the city of Chiang Mai, and yet it could be any number of places. While I guess the fresh produce up for sale is locally sourced, goods such as clothing and household items appear universal: it represents the tension between ideology and practice, globalism and globalisation.

Smell (on the internet; in the gallery)

If you search for “climate emergency” online, the first thing that comes up is a definition of the UN Environment Programme, which states: “Climate change is real and human activities are the main cause”. If you research further—or read the essay by Dr Jen Rae that accompanies the exhibition—you will find that 30% of greenhouse gas emissions come from the global food system alone and that an unhealthy relationship with food is a major contribution to current illnesses and death. Are we what we eat? If so, we are what we release. Environmental scientists advise that reducing carbon emissions is not enough: the planet needs drawdown and regeneration.

I have left the market, but its products follow me. Fruit has travelled to the next room with six prints on canvas plus an installation: a pile of cardboard boxes that, if the gallery were not in lockdown, would host fresh bananas, apples, pineapples, coconuts, oranges and pears. I am looking at Früchtlinge (2019) by Indonesian artist Elia Nurvista. The title derives from a fusion of the German words for fruit (Früchte) and refugee (Flüchtling). Reproductions of two famous sixteenth-century paintings by Italian artist Caravaggio are accompanied by vignettes that infiltrate contemporary references—buildings, street signs and EU flags—inside representations of colonial scenes. The fruit is challenged for its exotic connotation—they’re stamped with a sticker that could come from a supermarket as much as an immigration office. The Chiquita label on the bananas screams: “PSSST! I’m full of colonial sins”. Früchtlinge emphasises the parallels between food and human beings through stories of crossings, migrating and journeying—which gains further weight against the prediction that by 2050, one billion people may become climate refugees due to soil desertification. Nurvista asks, what is foreign to us? Othering, by means of cultural appropriation, discrimination and commodification, is an all-inclusive practice that can meet us everywhere, even when we think that we are sitting alone at the dinner table.

Früchtlinge is set in dialogue with New Romanticism (2020–21) by Lauren Dunn: a combination of photographic prints, a sculpture and a vinyl wallpaper that play with scale to idealise images of food while interrogating the underlying power dynamics behind their construction and circulation. There is an oyster presented like a mausoleum. It looks attractive. You can almost feel its scent and this impression is sinister—because the oyster resembles a human ear. The composition is very elegant, and the photograph is presented in a frame that confers it dignity and importance. Next to it, glued directly onto the wall, is a large picture of a woman tilting her head backwards, laughing. It could belong to an amusing anthology of advertisements that went viral on the internet, starring women beaming while eating a salad—a most conventional (or is that contemporary?) representation of the triad of beauty, joy and health. The images’ dominant palette is green. But far from evoking the colour of fresh food, this green seems to come from the land of the virtual. A distorted vegetable and an egg looking at its own food-wrapped reflection add on to the surrealist glare of Dunn’s installation.

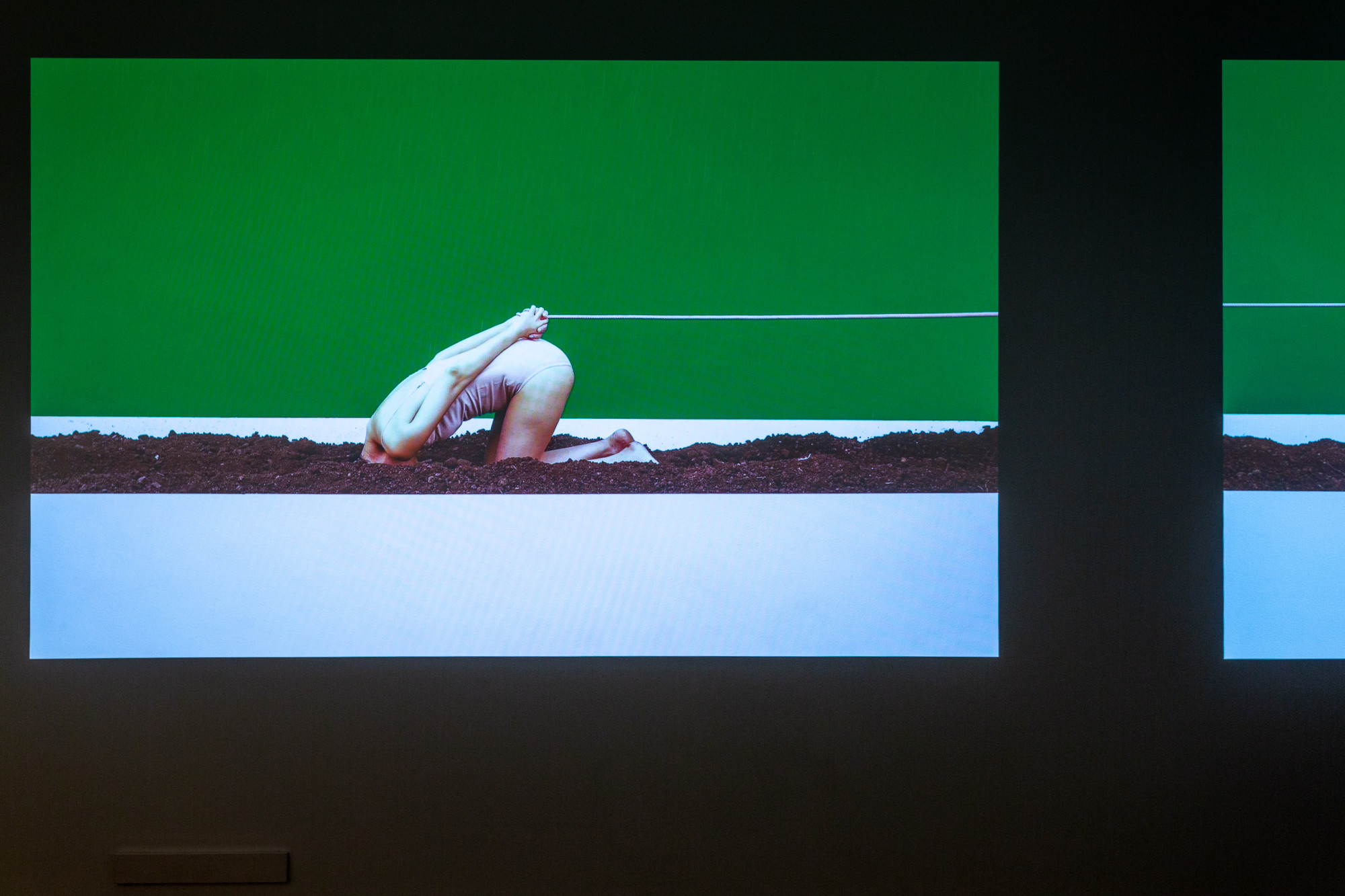

From food as an object to the objects that make food. Sophal Neak’s Rice Pot (2013) is a series of ten photo prints that capture women—friends and relatives of the artist in Cambodia—alongside their own kitchen tools. The models appear to me as they: show, cuddle, admire, present, hide, offer, pose with, carry, hold, and look into. While the sitters are portrayed as one thing with their belongings, the artist implies—through repetition (of an object) and difference (of poses and subjects)—that each pot conveys a unique, different meaning for each woman. Yet, there is a parallelism between food and gender. By following this thread, we find a circular ending: the final act is another video installation by Kawita Vatanajyankur, whom we met at the entrance of Fertile Ground. The Plough (2020) is a two-channel projection that begins with the image of a person, the artist again, embodying an animal that carries a plough. Ploughing was the first human-generated form of soil erosion, and Vatanajyankur reminds us that erosion is destroying the planet. The work continues with Vatanajyankur, who is now the plough, with her head stuck under the ground to resist the weight and effort of her own body; the subject-object is not only a worker but is also a woman.

Hunch (in my mind)

Fertile Ground speaks of colonial violence, social inequality and environmental disaster, alongside diasporas, and old and new modes of traveling. Yet the works that compose it are currently locked away from the public, enclosed like hostages, within the walls of CCP. What an irony. Among the many questions that emerged in my journey through this exhibition, there is one (which is in no way new) that has especially troubled me: is there really any truly constructive space for art to affect change around issues such as climate emergency and food crisis? The selection of artists and the tale that weaves their works together are wisely curated. But the risk is that the urgency of the message overtakes that of the art. Indeed, this danger is true of much art that attempts to deal with politically burning issues.

So, I borrow from a distinction that art critic Claire Bishop has recently proposed, between activism and dissidence. The first, Bishop says, manifests in the contexts of democratic societies, whereas the second is typical of authoritarian governments. It follows that dissidence is necessarily uninvited and can only take place through the format of an intervention, while activism cannot intervene but can be organised—however, I would like to suggest, it might also be curated. If we agree that taking risk is a move towards setting an example to take action, then by pursuing a visual engagement with the politics of food, the risk-taking action of Fertile Ground is a step towards success. But let me set the metalevel of this reviewing aside, and keep the focal lens on art. The circulation of images today is ubiquitous and hyper accelerated. On the contrary, IRL movement is inhibited. If exposed cleverly, can an image be a far-reaching and effective medium to motivate action? I would like to say ‘yes’ but I am afraid that a more grounded answer may require leaving art, as well, on its side.

Fertile Ground opened on 21 July and was scheduled to close on 5 September 2021. It has been extended due to lockdown. In the meantime—and although I inadvertently compound Dr Lembke’s observations—I hope that by bringing some of the exhibition’s provocations outside of the gallery and into your home, I have exposed the ever-present tension between apathy and action that Fertile Ground speaks to.

Miriam La Rosa is a Sicilian-born, Naarm/Melbourne-based art curator and PhD Candidate at the University of Melbourne. Her current research looks at notions of gift exchange and host-guest relationships in the arts residency, with the South as a geopolitical focus.