Walking through Every Brilliant Eye—a large survey of the NGV's holdings of Australian Art from the 1990s curated by Jane Devery and Pip Wallis—I was struck by how much it look like parts of Melbourne Now, the NGV's sprawling 2013-2014 snapshot of contemporary art practices in Melbourne. It is not only that many of the same names reappear, sometimes with work little changed by the twenty years separating the pieces currently on display from what was shown in Melbourne Now. More notable is the impression generated by this exhibition that the overarching tendencies or styles that appeared to jostle with one another for space in Melbourne Now are essentially unchanged since the 1990s: fussy installation art, political work of varying degrees of explicitness, video, John Nixon & Company, deliberately shoddy and makeshift 'grunge'.

On closer inspection, there are period markers everywhere, reminders of just how long twenty years is in terms of both technology and taste: baggy jeans, clunky 3D animation, the fact (coming in the form of a review in the pages of A Constructed World's Artfan magazine) that at the height of 'French theory' ACCA put on a show of Baudrillard's photography. Some of what has dated is obvious (Patricia Piccinini, whose work now seems barely legible as art; the lugubrious kitsch of Susan Norrie and Stieg Persson), while the work of some artists surprises in how little it has withstood the test of time. Ricky Swallow's early work, represented by his floor standing Darth Vader sculpture (Model for a sunken monument, 1999) and by two miniature science fiction scenes (from the series Even the odd orbi, 1999, originally shown in the one and only Melbourne Biennial of 1999), now seems like a period piece. Was it Charles Green who once referred, somewhat dismissively, to Swallow and some of his peers as 'funky'? The 'funkiness' of these impressively crafted little objects, so friendly in their invitation to peer into their fantasy world, now looks cute and mannered, a display of skill that ultimately rings hollow. While Swallow deliberately riffs on the aesthetics of action figures and Warhammer 40,000, time seems somehow to have closed the gap between his work and its models.

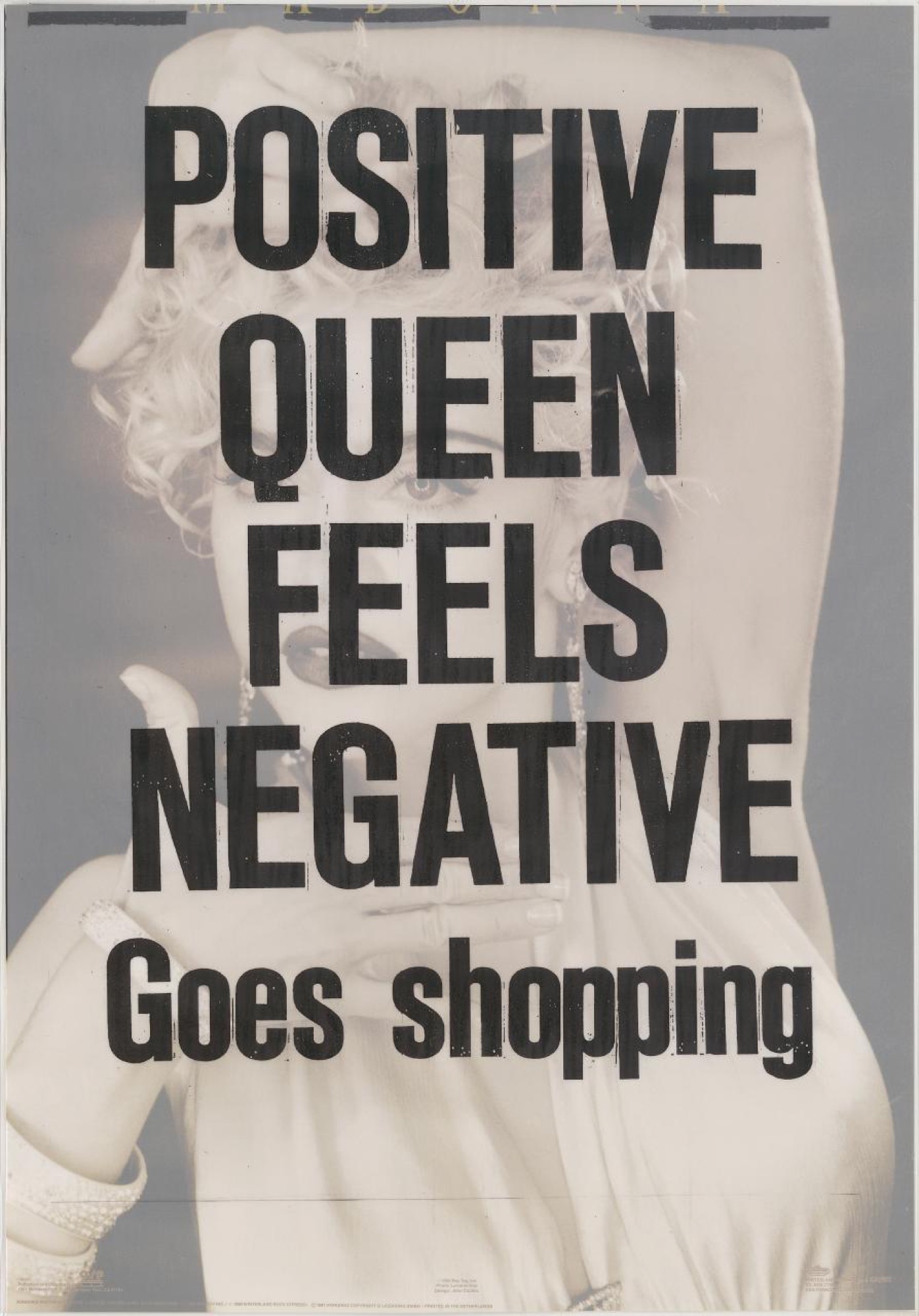

In terms of the politically motivated work on display, the more confrontational its tone and, paradoxically, the closer its tie to specific issue of the day, the better it has aged. Anne Ferran's I am the rehearsal master (1990), in which the artist recreates Charcot's famous hysteria photographs (in order, as the title indicates, to demonstrate their staged and constructed nature), provides an excellent example of the sort of aesthetic deficit that plagued much art of the period—the object itself adding nothing to the description of its 'meaning' provided by the title and wall text, offering no resistance, no density. In contrast, the billboard that hangs next to it, A cyberfeminist manifesto for the 21st century (1992) by the VNS Matrixcollective, despite (or perhaps partly because of) its garish appearance still packs a punch as a document of a time when a science-fictional image of the internet—as a sort of sublime new reality, rather than simply a medium of information that would be successfully integrated into everyday life—still appeared possible and could be associated with a utopian social radicalism. Similarly, David McDiarmid's Standard bold condensed (1994), a series of found images overlaid with screen-printed transparencies bearing mock newspaper-style headlines such as 'AIDS Victim Dies Alone: Family Profits', 'Sick Fag Spits on Sister' and 'White Priest Blows Cop: Pays for it', in its bold design and outrageous irreverence retains its force as a gesture of defiance against a conservative culture and its deficient handling of the AIDS crisis.

The spectre of authenticity was lurking around in the early 1990s: if this was the time of Take That, it was also that of Nirvana. One of the most interesting things about Every Brilliant Eye is the attention it brings to the now somewhat forgotten use of the concept of 'grunge' in Australian art criticism in the early 1990s. Coined by Jeff Gibson in an article in Art & Text, this term was used to characterise artists like Hany Armanious, Mikala Dwyer, and Dale Frank, whose work seemed to oppose the slickness of much art of the 1980s and 1990s by using found materials and toying with the abject. There are some interesting examples of 'grunge' in the show. In Lyndal Walker's 1997 photographs of the interiors of messy Melbourne share houses, for example, we can see a resistance to the dominant sub-Baudrillardian rhetoric of so much art of the 1980s that insisted on the colonisation of everyday experience by the spectacle. In these photographs, like in Dale Frank's untitled contribution to the Courts and jesters folio (1992), composed of roughly cut sheets of vinyl wallpaper secured on cardboard, the notion of a total transformation of life into an image is mockingly rejected through the invocation of a sort of authenticity deposited in the material reality of everyday life (dirty carpets, shoddy wallpaper, broken instruments).

This concern with materiality led Memo contributor Rex Butler to speak in 1995 of how certain currents of art in the 1990s suggested a return to the real in which 'tradition, authorship and expressivity might again be possible.' Where the pervading model of the artist in relation to their work in the 1980s had been irony, a distance from the art object and its reduction into a mere vessel of an immaterial signification, Butler found in some artists of this period a new investment in the material reality of the work and an embrace of the resulting opacity and ambiguity. The 'grunge' artists were not Butler's examples; in fact, he explicitly argued that the discourse around 'grunge' art paradoxically reaffirmed the very model of art it sought to disrupt, because these artworks became mere symbols of or statements about their resistance; not truly material but about materiality. Butler pointed to A.D.S. Donaldson as an example of the new sensibility he saw emerging, and his Cottons (1993), on display here, affirm Butler's reading of them. Minimal sculptural forms made from readymade rolls of cotton with bamboo hoops inserted at the ends and hung from the ceiling, they suggest some sort of domestic revision of the tradition of modernist abstraction without making any sort of statement about this, without transforming themselves into vessels of a meaning that would transcend their 'mute physical presence' (to use Butler's words).

In this regard, it interesting to look at the work associated with Store 5, an artist run space in Melbourne primarily showcasing work related to the tradition of geometric abstraction, operative between 1989 and 1993 that has developed a romantic aura in the decades since it closed and been the subject of a number of retrospective and commemorative exhibitions. There are very strong and often charming works on display here from artists associated with Store 5. Eugene Carchesio's tiny, hermetic abstract paintings and Rose Nolan's early and very Nixon-inspired icon works stand out. But looking at much of the work produced by the group, especially at the collective print portfolio The caboose (1992), one is struck by the question: is this really geometric abstraction, really an attempt to further this tradition, to do something new, something the artists could entirely invest themselves in—or is it rather the idea of such a practice? It is both, of course, depending on the artist, the work, and so on. However, the overwhelming impression is that it is not the material result, but the fact of their having been made, that is primary, which is reinforced by the presentation of publications and ephemera associated with Store 5 artists alongside these works.

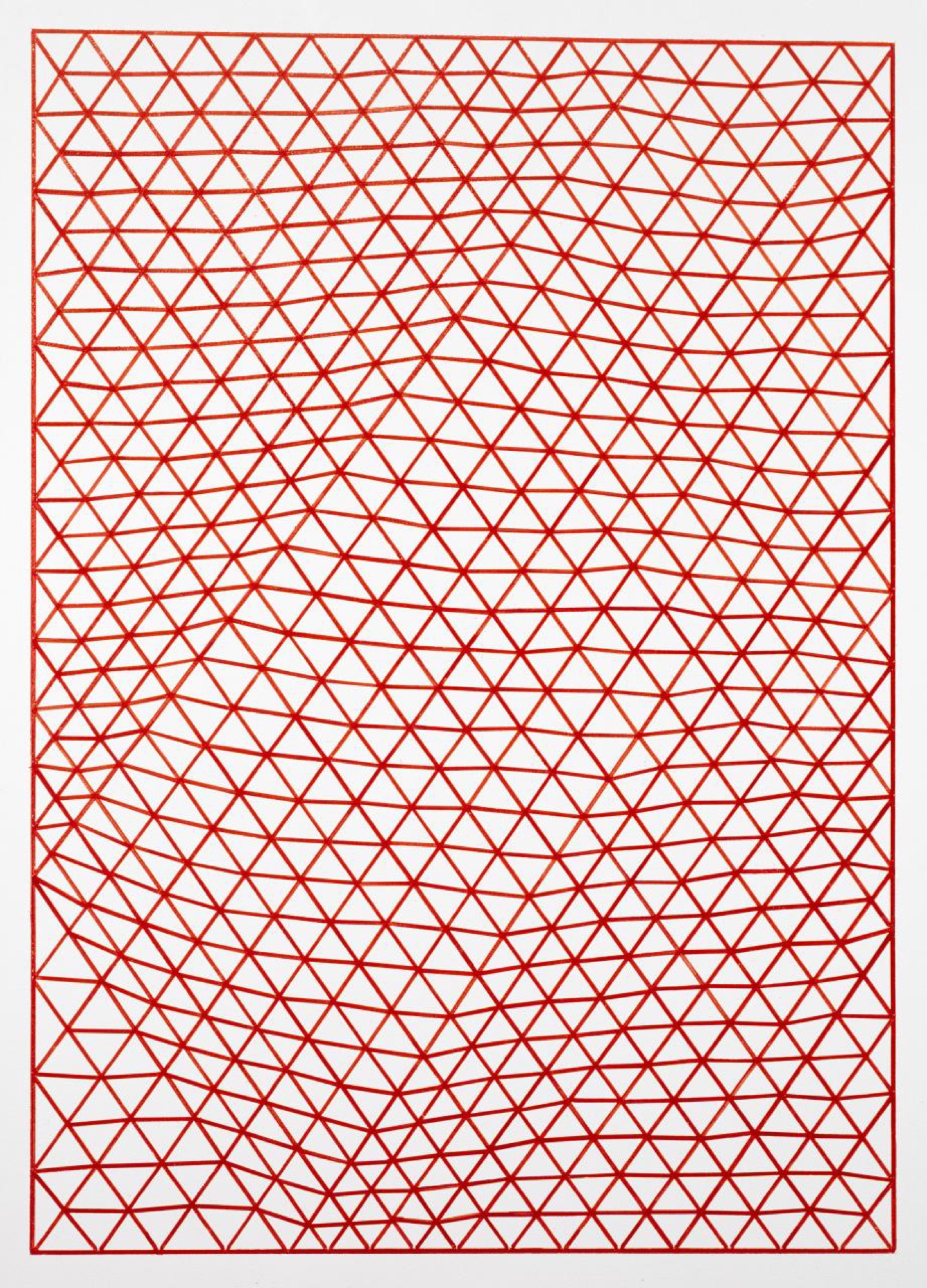

If the abstraction produced by Store 5 is less important in its aesthetic results than in its idea, what is this idea? Looking at Marco Fusinato's Paintings (1996) can help us think through this question. The work is composed of a set of variously sized monochrome red panels shown leaning against the wall, all of which were painted, the artist tells us, as quickly as possible. This is 'action painting' reduced to the action of uniformly covering a surface with paint, thus paradoxically erasing the trace of the gesture toward which the artist's description of the work draws our attention. The finished product certainly has its own punkish charm, but as Fusinato's later work demonstrates, he was clearly never interested—in the way that some of the other Store 5 artists could claim to be—in creating 'sincere non-objective art' (to use Robyn McKenzie's words). It seems to me, rather, that this work is primarily reactive: against the slickness of the 'mainstream' contemporary art of the 1990s, against the use of art as a transparent medium to address important issues, against the fascination with digital technologies. We understand more of the work if we see it as gesture than if we look at it as the result of a materially based practice; and this holds as well, even it is less obvious, for many of the other artists associated with Store 5.

The curators have chosen to present the works in this show with a minimum of contextualisation. Outside introductory comments that allude to some of the broader historical and political questions of the day, the curatorial commentary is restricted to wall-texts on major works in the show. Insofar as this places emphasis on the work itself (unfortunately not always well served by being shown in somewhat overstuffed rooms), it is admirable. However, in the case of a work like Fusinato's, one finds oneself looking for something more in the way of local context. Artists produce their work in relation to issues in the wider world, but also in dialogue with other artists—those whose work they admire and, perhaps especially, those in whose work they find something to object to and react against. Like all art worlds, those mini-worlds constituted by the art communities of each Australian city are composed of scenes—scenes that, even if on the surface they exhibit a jolly plurality, are often antagonistic toward one another. Such antagonism—a competition, ultimately, between different ideas of what contemporary art should be—seems important when considering the gestures made by Store 5 and by the 'grunge' artists. Of course, considering the web of personal and professional ties that bind together the major players in the Australian art world, we might have to wait some time before that version of the history of contemporary Australian art is told.

Francis is a writer and musician from Melbourne.

Title image: Marco Fusinato, Paintings, 1996, enamel paint on steel and composition board (a-e), 220 x 281 x 10 cm (overall), National Gallery of Victoria, Margaret Stewart Endowment, 1996, © Marco Fusinato/Licensed by VISCOPY, Australia.)