Emma Phillips: Too Much to Dream

Ella Cattach

There are three Dianes—two portrait subjects, one spectre—in Emma Phillips’ current exhibition of large-scale, predominantly black-and-white photographs which takes its title, Too much to dream, from a song by The Electric Prunes.

The first Diane, of Untitled (Diane washing dishes at her father’s house) and the unfocussed, tightly cropped colour triptych Untitled (Diane on her bed, smiling), both 2018, previously appeared in a key portrait from the artist’s 2017 exhibition at CAVES titled Greetings. There, in Untitled (Diane with pet rat), 2016, Diane gazed affectionately, knowingly, at the pet rat clinging to her shoulder. “do you miss the rats?” reads a line from Phillips’ intriguing bricolage text, which accompanies Too Much to Dream and is composed of “diary notes and sentences friends, family and portrait subjects’ have written, texted or spoken aloud, as well as excerpts from Clarice Lispector’s A Breath of life.” We might imagine that Diane, while washing dishes at her father’s house, flanked by neat rows of baby bottles to her right and a tin of baby formula to her left, replies without turning that she’s too busy to miss the rats.

The second Diane appears in Untitled (Denise and Diane twinning) (2018), though it is difficult to tell which of its two women she is. Their likeness, which we are commanded to look for by the parenthetical non-title, is obscured by the way they are posed together, dressed similarly but not identically. The women—one sitting in an armchair, the other balancing on the chair’s arm—press their foreheads together, so we can see just a sliver of one’s profile between the parted curtains of their separate-yet-together heads of hair. If they are twins, we can’t tell; their likeness is seductively suppressed by their pose. Atop the cabinet behind them are several kitsch sets of twin figurines posing just as cutely among family photos. The delirium of seeing double, or triple, as in the hazy triptych of the first Diane, floods across the exhibition: “hallucinations hallucinations hallucinations,” goes a line from Phillips’ text collage, which is full of dreams and of madness (the madman is a waking dreamer, said Schopenhauer).

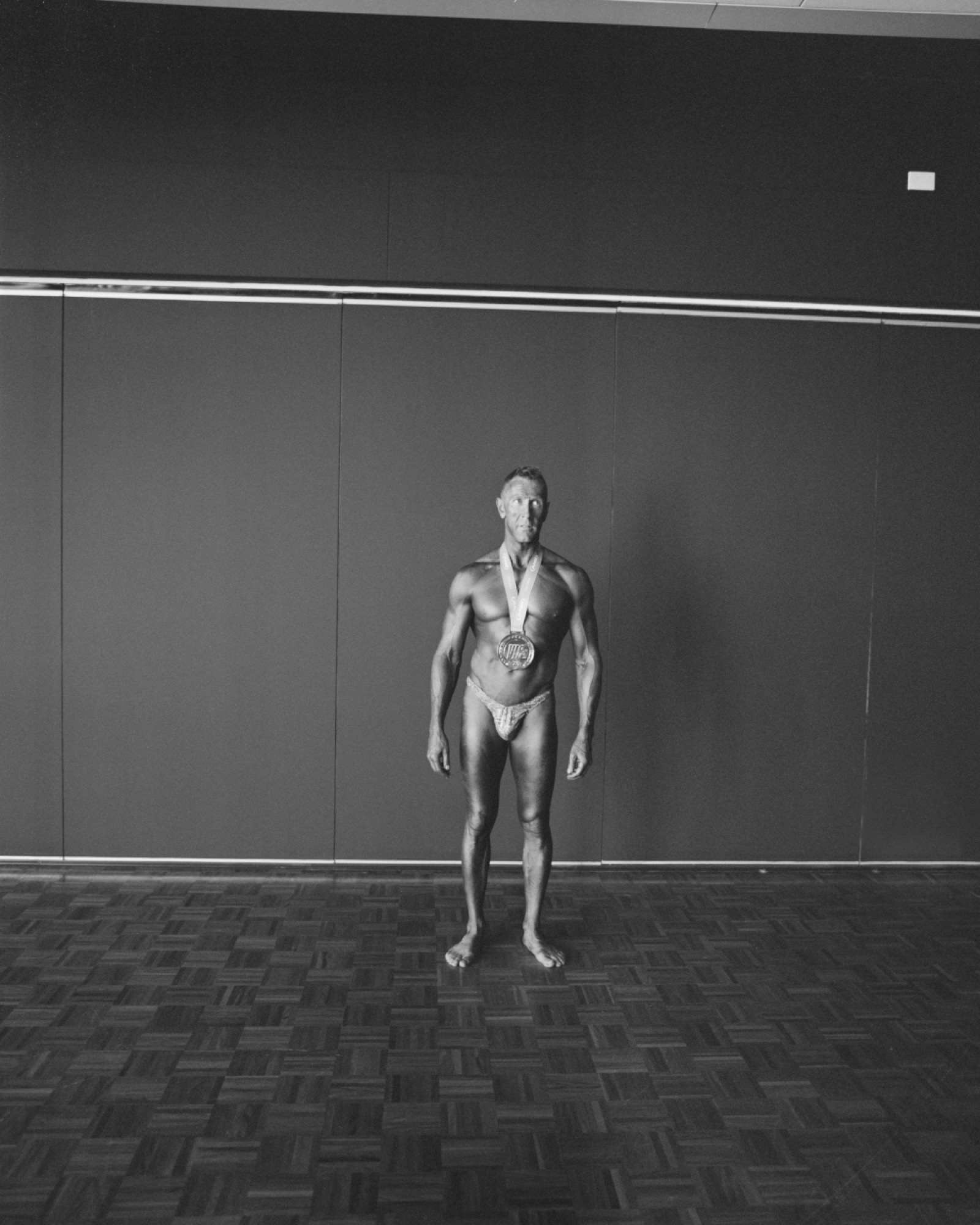

Twinning cues the third Diane: Diane Arbus, whose influence is most legible in the outlier photograph of the exhibition, Untitled (muscleman), 2018, calling up in both subject and composition Arbus’ Muscle man in his dressing room with trophy, Brooklyn, N. Y. 1962. Phillips’ muscleman occupies curious territory, almost prohibitively placed on the back wall of the gallery’s office, where he is visible, awkwardly, from Room One of the gallery space through the office’s doorway. His distance from the rest of the exhibition deepens his distance within the photograph from the camera. In all his bronzed muscular robustness (rewarded only with a medal around his neck, unlike Arbus’ proud trophy bearer), he appears comically small as if foreshortened—a caricature of masculinity at the fringe of Phillips’ vision, and the only man depicted in this collection of her work. His isolation was no more evident than on the exhibition’s opening night, during which the door to the office was, for stretches of time, closed, so that diligent punters abiding by the dictates of their room sheets asked permission to enter the office and see him.

The third Diane is also gestured to in Phillips’ striking photograph of an albino teenage girl. Untitled (Lucy at Sammy’s house), 2018, evokes Arbus’ photographs of a young female albino sword swallower in Albino sword swallower at a carnival, Md. 1970 and Albino sword swallower and her sister, Hagerstown, MD., 1970. That the albino girl in Phillips’ photograph is one of two—like the sword swallower whose sister is albino—is hinted at in its non-title. Lucy and Sammy are a teenaged albino duo with a public profile. As news.com.au reported in 2017, “Two Geelong girls with albinism have started an Instagram fashion account and it’s taking off.” The portrait of Lucy is distinct from the other portraits in the exhibition in that we can see the subject’s face clearly. Its sharpness is made sharper by the fact that she is blind; the one we can see can’t see us. She gazes through us, as if into herself, while we examine the pure white strands of her eyelashes and hair.

In Greetings, Phillips photographed her subjects outside on the street. Now, she has entered their homes. The first Diane is not the lone returning cast member. The young woman in the portrait nearest to that of Lucy—Untitled (Amber on her grandmother’s bed), 2018—appeared in the earlier exhibition’s Untitled (Amber in leopard print), 2016, striking a pose—hand almost on hip—in a leopard print jacket over matched but mismatched leopard print tights. The progression from the tiny inkjet print portraits in Greetings to the large-scale gelatin silver and chromogenic prints in Too Much to Dream is startling, not least because of the radical shift in scale. The blurriness of Diane and Amber’s faces in the new photographs is also suggestive of a new intimacy between photographer and subject—reinforced by the fact that both are pictured on beds. This intimacy, we imagine, has been cultivated since Phillips’ earlier show, where the impassive formality of the title Greetings suggested first meetings.

The portraits of Lucy and Amber are separated by a stunning shot of a tree—Untitled (pollarded tree), 2018—with its limbs cut off, raw and disfigured. Together with and on either side of the tree, the vulnerability of Phillips’ portrait subjects is so apparent. Vulnerability is a convincingly essential aspect of her work, and it sits strangely. Arbus confided to a friend that photographing people could be compared to “flattening them on the wall like a butterfly impaled on a pin.” The landscapes and still lifes in Too much to dream—which include an outstretched arm of a butterfly hanging mobile in Untitled (butterflies), 2018—sit on the same plane as Phillips’ portraits. They are presented in the same way, at the same scale. How are we to read the whiteness of the unglowing glow-in-the-dark stars and butterflies on a white ceiling in Untitled (synthetic stars), 2018? As an aesthetic complement to the portrait of the albino girl?

By invoking the confessional, Phillips’ text can be read as a counteroffer, wherein which she exposes her own vulnerability. The text makes claims for candour: “this isn’t a narrative, it’s a primary life that breathes breathes breathes” and “i am always sincere.” The latter statement is naturally subject to the paradox of the Cretan liar—a fact it draws attention to on the second page of the text with reference to “the great pretender.” The authorial indeterminacy of the text’s fragments invites decoding and plays against the transparency of the confessional. It also offers meditations on the fraught relationship between photographer and subject. We might comfortably attribute lines such as “still haven’t found a way to photograph people” and “I introduce you to myself, visualise you in snapshots” to the photographer, and reckon that the question mark-less question “is your camera heavy,” is an utterance of one of her subjects. The seduction that takes place between photographer and subject is a curious one. The photographer seduces the subject, but the subject is seduced by their own image: “I would love to get into modelling sometime next year, or even learn guitar” is another line we can imagine attributed to one of the young women photographed. The artist’s textual display of vulnerability may not be equivalent to that of her portrait subjects, but it serves to show that just as they are in her text, she is in their photographs.

I have been calling, not without some unease, Phillips’ portrait subjects by their real names, while also treating them like characters in a novel. In A Breath of life, Clarice Lispector struggles, as Arbus does, to be compassionate to her characters: “I live in the living flesh, that’s why I make such an effort to give thick skin to my characters. But I can’t stand it and make them cry for no reason.” Phillips’ portraits are vastly gentler, and tenderer, than Arbus’. But ambivalence dictates that there is always a measure of hate in love, and violence in tenderness.

Can a woman in a photograph take on an unreality and become fiction? When I dream about someone real, is it them or is it me? Too real is this make-believe.

Ella Cattach is a Melbourne-based writer.